2.1.2 Children and young people at Lake Alice Tamariki me ngā rangatahi ki Lake Alice

61. We estimate between 400 and 450 children and young people went through Lake Alice between 1970 and 1980. Records from Oranga Tamariki show the Department of Social Welfare admitted 203 children and young people to Lake Alice (“individuals admitted by the Department of Social Welfare”).[125]

We have limited information about survivors who did not have Department of Social Welfare involvement. However, we believe they were a significant cohort. From records and interviews with survivors we have been able to identify 362 children and young people who were admitted to Lake Alice in this period, some of whom would have been in the wider hospital rather than the unit.

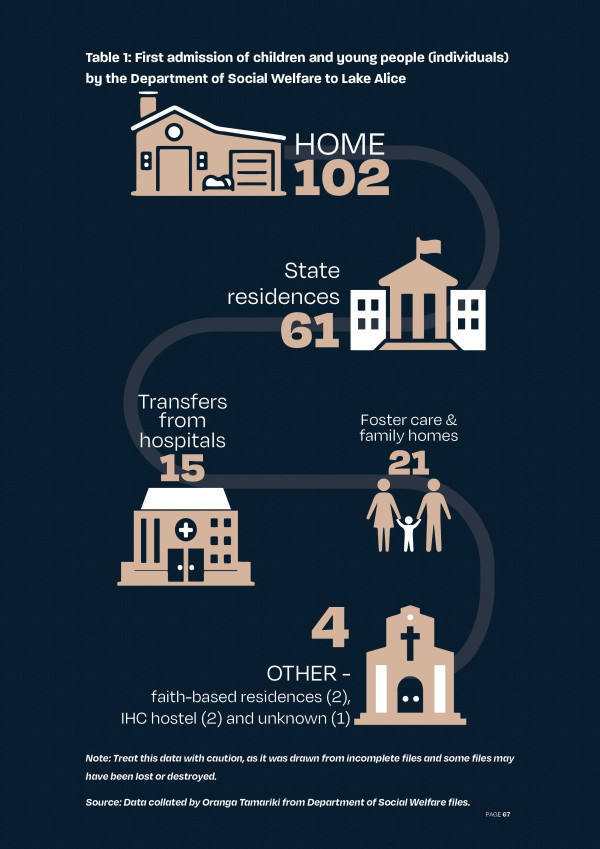

62. Of the individuals admitted by the Department of Social Welfare, about half had their first placement at Lake Alice from home (102)[126] and about half from care placements (101).[127]

The breakdown of first admissions is shown in Table 1.

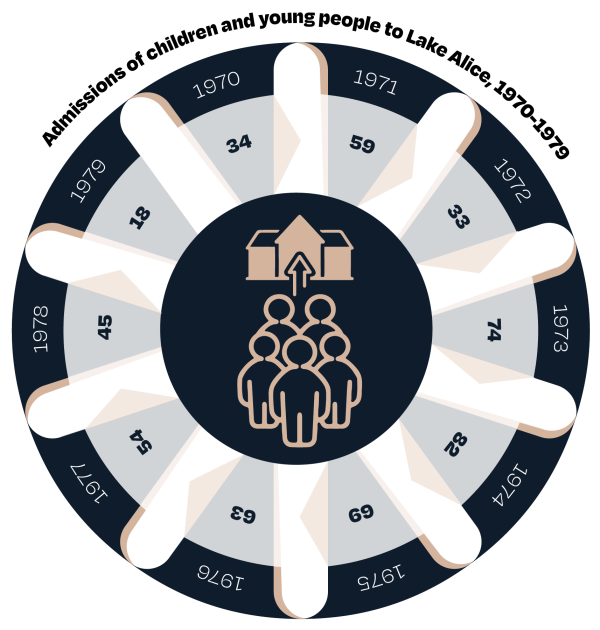

63. Many survivors spent time in several different care placements. For example, if a survivor’s first admission to the unit was from home they actually may have been in a care placement before that and returned home for a short time before going to the unit. Lake Alice annual reports show admissions of children and young people (under age 17), initially to the general hospital and later to the unit, grew steadily during the early 1970s, peaking at 82 in 1974 before tapering off in the second half of the decade. The annual reports contain no discharge figures and tell us only the number of admissions during any given year, not the number of individuals admitted.

Table 2: Admissions of children and young people to Lake Alice, 1970–1979

Source: Lake Alice annual reports for 1970–1979.[128]

Source: Lake Alice annual reports for 1970–1979.[128]

64. Some children and young people were admitted and discharged more than once, meaning that of the 531 admissions for the period, some of these will be the same children and young people returning to the unit multiple times. For example, the 203 children and young people admitted by the Department of Social Welfare had a total of 273 admissions (five were admitted to the hospital’s national security unit, a maximum-security villa).[129] These records show 44 children and young people (about one in five) were admitted more than once, including 14 admitted at least three times, five admitted at least four times and two admitted five times.[130]

Ngā ara whakauru - Pathways to admission

65. Each of the main pathways to admission at Lake Alice is discussed next; from home, State residences, hospitals and child health clinics.

Ngā whakaurunga i ngā kāinga - Admission from home

66. Most of the children and young people who went to the unit were living at home before their first admission. Some had direct involvement by the Department of Social Welfare and others were admitted by their parents or guardians, often on referral from general practitioners or child health care clinics.

67. We received accounts from 31 survivors, or whānau members, who were admitted into Lake Alice directly from their homes, 9 girls and 22 boys. 10 were referred to Lake Alice through medical services such as child health clinics, half of these by Dr Leeks.

68. Some survivors told us that difficulties at school preceded their admission to the unit from home. For example, Mr Leota Scanlon believes his school contacted the Department of Social welfare, which led to his admission to the unit:

“The social worker told Dad that I needed a psychiatric evaluation because of the fights I was having at school. The social worker told him that they wanted to send me to Lake Alice Hospital. I knew my Dad couldn’t understand what they were saying because he couldn’t speak English. The social worker then gave me the phone to talk to Dad and I said to him in Samoan that I didn’t want to go to that place, being Lake Alice. I told him in Samoan because I didn’t want the Principal to understand what I was saying. Dad agreed to send me to Lake Alice. I was taken straight to Lake Alice from school by the social worker.”[131]

69. For disabled survivors, their parents or guardians often thought the survivor would get better care at the unit than their families were able to provide. Mr BZ (Ngati Porou) told the inquiry his grandparents thought the unit “would be the best place to help with my epilepsy. It was getting hard for them to look after me. They told me I would be safe, but they did not realise it was a bad place”.[132] Mr BZ told the inquiry his epilepsy got worse while he was in the unit because he was getting electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).[133]

70. Other times, survivors’ parents were seeking help to manage their tamariki behaviour. For example, Mr EN told us he first went to see Dr Leeks after his mother sought help managing his behaviour, which included fighting at school and truancy.[134]

“Dr Leeks and I had five or so visits. He just sat there and stared at me with a kind smile. Mum would have to leave the room till it was over. He asked me some questions, can’t remember what they were. I was taken to Lake Alice after that. I never knew why I was there. No one told me. No one asked me if I wanted to go.”[135]

71. Survivors were often referred to the unit by doctors. Ms Sharyn Collis went to see Dr Leeks at a child health clinic. She said Dr Leeks used admission to the unit as a threat:

“Leeks kept telling me when I was in Manawaroa [health clinic] that I would end up at Lake Alice if I didn’t behave. He used Lake Alice as a tool to threaten me. I felt trapped and I did not have any protection at home either. Leeks, my GP [general practitioner], my mother and others were all a part of sending me to Lake Alice.”[136]

Ngā whakaurunga i ngā kāinga Kāwanatanga - Admission from State residences

72. Dr Leeks visited to consult at nearby residences, Kohitere (a home for boys aged 14 to 17)[137] and Hokio Beach School (which housed boys aged 12 to 14)[138] to provide psychiatric services to some residents from 1971.[139] His visits were described by the Kohitere principal as ‘spasmodic’, and the time he gave Kohitere ‘very limited’.[140] The Hokio principal had similar complaints, writing in 1972 that psychiatric services to the school were “well below the level that could be reasonably expected”.[141]

73. Survivors admitted to the unit from residences often felt the reason for their admission was for punishment. Mr Tyrone Marks and Mr Rangi Wickliffe both said they were admitted to Lake Alice from Holdsworth as a ‘deterrent’ for their misbehaviour. Mr Marks’ admission files contain a document from the principal Mr Marek Powierza, who noted the admission was “due to persistent absconding and subsequent burglaries and other misdemeanours whilst missing from Holdsworth”. [142]

74. Of the individuals admitted by the Department of Social Welfare, 16 boys were sent from Holdsworth, for admission periods ranging from around two to 20 weeks, the average being 10 weeks.[143] Three staff were instrumental in the admissions from Holdsworth: acting principal John Drake, deputy principal Duncan McDonald and founding principal Marek Powierza. Mr Powierza said, “Children were sent to Lake Alice if their behaviour could not be controlled”.[144]

75. Mr John Watson, a housemaster at Holdsworth from 1972 to 1975, said he learned of the referrals to Lake Alice on the basis of persistent absconding and aggressive behaviour and was concerned about the reasons for referral.[145] He believed the school could have managed the boys’ behaviour and did not think it was necessary to send them to a psychiatric hospital.[146]

76. Evidence we gathered suggested similar reasons for admissions from Kohitere and Hokio. The Ministry of Social Development found that threats, such as being sent to Lake Alice, were also used by some staff.[147] The ministry said some boys who “did not respond to any discipline” were sometimes sent to Lake Alice for periods of up to two months.[148] One survivor described running away from serious violence at Kohitere.[149] He was picked up and taken straight to Lake Alice.[150] He said there was “nothing wrong with me mentally”, so there was no psychiatric reason for such an admission.[151]

77. Of the individuals admitted by the Department of Social Welfare, 19 boys were sent from Kohitere, 11 for behavioural reasons, seven for wellbeing or mental health reasons, and one for both reasons.[152]

78. Of the individuals admitted by the Department of Social Welfare, nine were sent from Hokio. Survivors told us Hokio was a violent place[153] and sexual abuse by staff was common. Many survivors told us they did not have a mental illness, but no one bothered to find out if their behavioural difficulties were the result of sexual abuse.

Ngā whakawhitinga i ngā hōhipera - Transfers from hospitals

79. Some survivors were transferred to the unit from other psychiatric and psychopaedic hospitals, either temporarily or permanently.

80. Often these survivors had experienced several care placements and significant abuse before their admission to other hospitals and their transfer to the unit. For example, survivor Sharyn Shepherd, born intersex, was sexually abused in various placements including Mount Wellington Residential School, Ōwairaka Boys’ Home and several foster care placements.[154] She developed an eating disorder due to a lack of self-worth as a result of the sexual abuse and was admitted to the psychiatric ward of New Plymouth Hospital and then to the unit.[155]

81. Some survivors were temporarily transferred to the unit from other hospitals. For example, one survivor told the inquiry he was transferred to the unit for three days when he refused to return to Wakari Hospital in Dunedin, where he was being regularly sexually abused:[156]

“The effects of the abuse I suffered and witnessed were compounded by my isolation from my family and the protection and support they may have been able to provide to me. In hindsight I wonder why the focus on these occasions was on chemical sedation, control and force rather than investigating the cause of my distress.”[157]

82. It appears transfers occurred between the Kimberley Centre and the unit, either on a temporary or permanent basis. The Kimberley Centre was a residential psychopaedic hospital, primarily for people with a learning disability, cognitive impairment and neurodiversity. Survivor Walton James Mathieson-Ngatai said, “quiet kids from Lake Alice would go over to Kimberley, and the kids from Kimberley who got up to mischief were dropped off at Lake Alice. If the kids from Kimberley behaved, then they would go back to Kimberley”.[158] He particularly remembered one incident in 1972 when about six children came from Kimberley in a van:

“One of the children from Kimberley was just five years old. He used to have fits, epilepsy, and they would give him ECT. They brought him over from Kimberley to give him ECT at Lake Alice.”[159]

83. We have evidence of Dr WF Bennett, the medical superintendent of Kimberley, agreeing with Dr Pugmire to transfer one of his patients to Lake Alice in exchange for a female Lake Alice patient.[160] We also know Dr Leeks regularly visited Kimberley to consult with staff on adolescent patients, some of whom he admitted to the unit.[161]

Ngā whakaurunga i ngā whare hauora tamariki - Admissions from child health clinics

84. Some children admitted to the unit were referred from child health clinics. These clinics were the main referral and treatment centres for children with psychiatric and emotional problems in the early 1970s.[162] Although these clinics were initially intended as stand-alone community clinics, it eventually became common for them to be located on hospital grounds.[163] In many cases, admissions recorded as being from home or foster care would have come through a child health clinic referral.

85. Referrals to child health clinics were through general practitioners, although schools, social workers and parents were also involved.[164] A 1973 report by Dr Alan Frazer about treatment facilities in the Wellington area suggested child health clinic services were generally “orientated to the ‘middle-class’ family”, whereas children from poorer families were squeezed out of the system and tended to be held in social welfare homes.[165] Most of those assessed or treated by these clinics did so as outpatients and remained in their own homes.

86. In 1971, Dr Leeks was appointed to the Palmerston North child health clinic and the Palmerston North Hospital Board. He then expanded the services offered by the clinic and established new clinic branches at Lake Alice and in Whanganui.[166] Dr Leeks also gained the agreement of the Lake Alice medical superintendent, Dr Pugmire, to admit ‘disturbed adolescents’ to the hospital.[167] In many ways, this marked the beginning of the unit. The child health clinic at Whanganui, where Dr Leeks worked, became a major source of referrals to the unit.[168]

87. In theory, clinic referrals involved some form of screening, but evidence from survivors and subsequent reviews of diagnoses by psychiatrists suggests even patients who received a formal diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder were not, in fact, always mentally ill. Even at the time, government officials noted the lack of clear clinic referral processes. In 1975, Dr Frazer wrote there was general agreement children referred to the unit should be “fairly severely disturbed [but] this is by no means the case”.[169]

Ngā kāhua o ngā tamariki me ngā rangatahi i te manga - Profile of the children and young people at the unit

88. This section discusses the 203 individuals admitted to Lake Alice with involvement by the Department of Social Welfare in terms of their age, gender, ethnicity and disability.

Ngā pakeketanga o ngā tamariki me ngā rangatahi i te manga -

The age of the children and young people at the unit

89. The median age of the individuals admitted by the Department of Social Welfare was 13 at first admission, and the youngest was eight.[170] Survivors told us about a child who was four or five when they spent time at the unit.[171] We were able to confirm through admission records that a four-year-old child was admitted to the hospital in 1974 with his mother.[172] The youngest child we have been able to identify as being treated in the hospital was admitted in 1978 and was five years old.[173]

Ngā ira o ngā tamariki me ngā rangatahi i te manga - The gender of the children and young people at the unit

90. Significantly more boys than girls were admitted to the unit. Of the individuals admitted by the Department of Social Welfare, 165 were boys and 38 were girls (including one intersex survivor).

91. If we separate admissions by pathway, 23 of the 102 individuals admitted from home were girls (23 percent) and 15 of the 101 individuals admitted from residences, foster care, and transfers from other hospitals were girls (15 percent). See Table 1 for a complete list of care settings.

Ngā mātāwaka o ngā tamariki me ngā rangatahi i te manga - The ethnicity of the children and young people at the unit

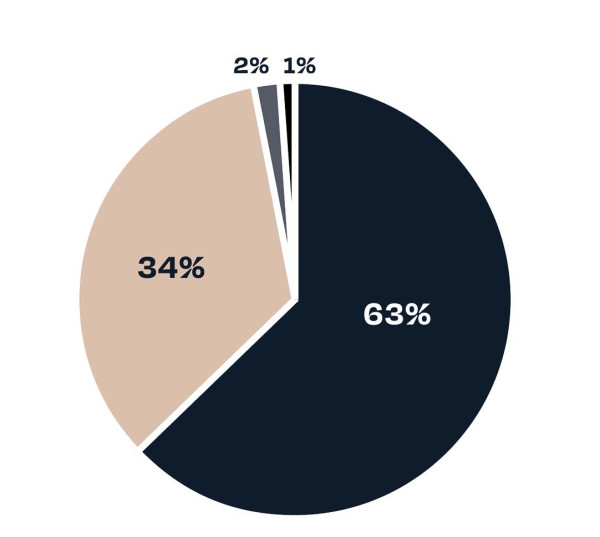

92. Of the individuals admitted by the Department of Social Welfare, 192 had an ethnicity recorded, although in the 1970s ethnicity records were often incomplete or inaccurate.[174] Contemporary studies have shown social workers and NZ Police often relied on highly flawed methods, such as ‘sight identification’, to determine ethnicity.[175]

93. Several Māori survivors told us their Department of Social Welfare files incorrectly recorded them as European. A Samoan-Rarotongan-Māori survivor was recorded as being Māori only.

94. Tamariki and rangatahi Māori were over-represented in admissions to the unit in comparison to the total population. Of the 192 individuals with a recorded ethnicity, 121 (63 percent) were recorded as European, 66 (34 percent) as Māori or Māori-Pacific, three (two percent) as of Pacific descent, and one (less than one percent) as of Indian descent.[176]

95. The over-representation of Māori was greater for admissions from residences, foster care, and transfers from other hospitals (see Table 1 for a complete list of care settings). For admissions from home, 27 individuals were recorded as Māori or Māori-Pacific (29 percent). For survivors whose first admission was from care settings described above (and for whom an ethnicity was recorded) 24 individuals were recorded as Māori (41 percent).

Pārongo hauā mō ngā tamariki me te hunga rangatahi i te manga - Disability information about the children and young people at the unit

96. We know from survivor accounts some disabled children and adults spent time in the unit and the wider hospital. We do not know the number of disabled children and young people who were admitted to the unit due to incomplete records, issues with misdiagnoses and changing understandings of disability. Survivors’ experiences of ableism[177] are discussed later in this chapter.

Te roa o te noho ki te manga - Length of stay at the unit

97. We know from survivor accounts and hospital records that the length of time individuals spent at the unit varied. The individuals admitted by the Department of Social Welfare spent an average of 29 weeks (203 days) at the unit, although 19 spent more than 600 days in the unit (whether from a single admission or repeated admissions).[178] The shortest time at the unit was three days, and the longest continuous time was almost 203 weeks (1,421 days). We do not know whether the length of stay varied for children and young people who did not have Department of Social Welfare involvement.

Ngā take i whakaurua ai ki te manga -Reasons for admission to the unit

98. Children and young people came to Lake Alice for many different reasons, but one common thread was the experience of significant abuse suffered beforehand. Often their parents, guardians or the Department of Social Welfare were struggling to manage their behaviour – frequently itself the result of the trauma – or other suitable residential options were lacking. In most cases, we found no evidence of a formal psychological or psychiatric assessment or diagnosis before admission or treatment.

99. Survivors told us that the root cause of the behaviour was not addressed and that if it had been, psychiatric intervention would not have been deemed necessary. For example, many survivors were struggling to cope with sexual abuse at home before their referrals. Ms Sharyn Collis told us after being raped at age 14 she began acting out and was sent to counselling with Dr Leeks and admitted to the unit from there.[179] She told us:

“My mother’s attitude was that it didn’t happen and I was lying or I deserved it. I started acting out like running away and not attending school. I was disruptive at home and swearing all the time, but that was typical of a rape victim, I guess.”[180]

100. Some survivors told us trauma as a result of abuse continued to be misdiagnosed on their admission into the unit. Ms Sunny Webster, discussing her diagnosis as shown on medical records, told us:

“I was diagnosed in Lake Alice with reactive depression, hysterical character disorder.[181] This is not what was wrong with me and the document proves that I was misdiagnosed. Nowhere on there does it say that I was a victim of sexual abuse, and that was the problem.”[182]

101. Children from State residences were sometimes transferred to the unit after experiencing abuse. Housemaster Watson said boys arriving there were “very vulnerable, seriously disturbed and in need of care and protection” and as a result demonstrated extremely volatile behaviour.[183] Some staff understood that prior experiences of abuse contributed to the boys’ behaviour,[184] but the school’s response took no account of this.

102. Some survivors have told the inquiry that they had no understanding of why they were placed at the unit, and only learned of their diagnosis later in life. One survivor, Ms Robyn Dandy, recalled:

“None of us children knew why we were at Lake Alice. We thought it had been because we were naughty for things such as shoplifting or running away from home. We were all just normal kids – none of us seemed to have mental problems. I note my records say I had a ‘personality disorder’. The only problem I had was a mother who did not love or care for me.”[185]

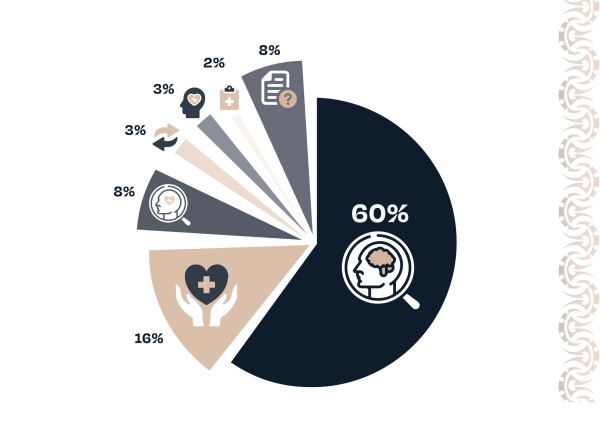

103. Department of Social Welfare records confirm ‘behavioural’ was the most common reason for referrals to Lake Alice. The Department of Social Welfare’s 273 admissions were categorised as:

103. Department of Social Welfare records confirm ‘behavioural’ was the most common reason for referrals to Lake Alice. The Department of Social Welfare’s 273 admissions were categorised as:

- behavioural: 164 admissions (60 percent)

- wellbeing or mental health: 44 admissions (16 percent)

- behavioural and wellbeing or mental health: 23 admissions (eight percent)

- transfer: nine admissions (three percent)

- Mental Health Act 1969: eight admissions (three percent)

- ongoing treatment or review of medication: four admissions (two percent)

- unknown reason: 21 admissions (eight percent).[186]

104. Dr Leeks said at first the unit tended to take adolescents considered ‘uncontrollable’ and posing problems for the Department of Social Welfare.[187] He said: “some of these children do not need to be in hospital, but apart from the child unit there has been nowhere for them”.[188] The hospital’s administrator at this time, Mr Thomas Henricus van Arendonk, said in 2001, that the children and young people there “were not really mentally ill.[189] Rather, they were problem children who had run out of help”.[190]

105. There was a distinct haphazardness to the admission of children and young people to the unit, and Dr Leeks said the unit grew in an uncontrolled way.[191] After Dr Leeks left Lake Alice, an internal Department of Education memorandum noted he had been admitting “all and sundry”.[192] Many felt the Department of Social Welfare used the unit as a ‘dumping ground’ for children whose behaviour was considered too challenging for other residential institutions. For example, Mr Craig Collier, a teacher at the unit’s school from 1977 to 1978 said: “Some of these children displayed behaviours such as hyperactivity, Asperger’s and anti-social behaviours. I believe that the [unit] seemed to be a dumping ground for those who were not able to be handled by schools or other institutions.”[193]

106. However, nurse aide Charles McCarthy recalled the behaviour of children in the unit seemed “like [that of] any other young person”.[194] Social worker Brian Hollis said, “I did not see any of [the boys] needing long-term treatment in a psychiatric hospital. Most of them, I thought, should simply be at Lake Alice for assessment.”[195] Former Lake Alice nurse Jack Glass said it was his perception “most of the adolescents had parent problems more than anything else”. He said they, “came with criminal or behavioural problems, not necessarily psychiatric problems”.[196]

107. After reviewing more than 90 cases, Sir Rodney Gallen said some children had been diagnosed with some form of mental illness, but the vast majority had no such diagnosis and were admitted for behavioural reasons:

“They were in fact presenting behaviour problems which for one reason or another were not controllable by the persons who had responsibility for them, nor had those behavioural problems been controlled, in some cases, by placement in other institutions … some had been subjected to severe physical and sexual abuse before their admission, others had suffered some kind of trauma which had affected their ability to integrate into the community.”[197]

Ngā tūtohitanga - Summary of findings Ngā āhuatanga i whakaurua ai te tangata ki te manga - Circumstances that led to individuals being placed in the unit

The Inquiry finds:

- Most children and young people at the Lake Alice Hospital child and adolescent unit were admitted for behavioural reasons, often arising from tūkino - abuse, harm or trauma, rather than mental distress.

- Social welfare involvement was a common pathway of admission to the unit, disproportionately affecting Māori. About 41 percent of those admitted from social welfare residences were Māori, and about 29 percent of those admitted from home with social welfare files were Māori. Poor quality records make precise figures impossible.

- The Department of Health, Department of Social Welfare and staff at the unit did not have proper processes in place to ensure the lawful admission, treatment and detention of children and young people in the unit.