Chapter Three: Hebron Trust Upoko Tuatoru: Te Tarati o Hebron

Whakatakinga

Introduction

1. It’s important to understand how Hebron Trust was established and operated, Brother McGrath’s role in this, and the involvement of the State which approved Hebron Trust to be a State approved provider of care. We’ll then outline the pathways or circumstances that led to tamariki and rangatahi (usually teenagers, although some as young as 8), coming into the care of Hebron Trust.

2. We set out findings at the end of this chapter.

Ka pōhiritia te Rangapū e te Pīhopa Katorika o Ōtautahi kia whakaritea he manatū mō ngā rangatahi kāinga kore me ngā tamariki noho tiriti

Christchurch Catholic Bishop invites Order to set up youth ministry for homeless youth and street kids

3. After the Order left Marylands in 1984, it had to make major decisions about how it was going to continue to operate in Aotearoa New Zealand, if at all.

4. In January 1986, a two-day meeting was held at the Australian headquarters of the Order in Burwood, Sydney. The meeting was attended by Bishop Hanrahan from Christchurch.[202] Bishop Hanrahan saw a growing problem with homeless people or ‘street kids’ in Christchurch and invited the brothers to establish a youth ministry to support at-risk young people[203], many of whom were Māori.[204] Bishop Hanrahan felt he was unable personally to respond to the needs of these young people but felt the church had a role in reaching out to them.[205]

5. Brother McGrath had a key role in scoping and implementing Bishop Hanrahan’s vision and the church’s role.[206]

6. Brother McGrath delivered a report to Bishop Hanrahan and the Provincial of the Order, summarising his impression of the need for services and made a number of recommendations to the brothers about accepting the Bishop’s offer to establish these services.[207]

7. Brother McGrath suggested the Order provide a house for emergency accommodation.[208] He outlined a need to help inner city street kids, who had been in other institutions or ostracised from their family, and a need to help families living in the suburbs, who were excluded from welfare.[209]

8. On 8 December 1986, Brother Pius Hornby wrote to Brother McGrath to say that his report had been received enthusiastically by the Provincial Council. The Council wanted Brother McGrath to continue his research until the “appropriate time for more formal arrangements”.[210]

Ka hoki anō a Parata McGrath ki Aotearoa Niu Tīreni ki te mahi i Ōtautahi

Brother McGrath returns to Aotearoa New Zealand to work in Christchurch

9. After carrying out the scoping exercise, Brother McGrath remained in Christchurch, working under the umbrella of Te Roopu Awhina[211] and the supervision of Catholic Social Services, while the Order and Bishop Hanrahan worked out an agreement.[212] On 24 December 1986, the Bishop sent Brother Pius Hornby an undated apostolic employment agreement between the diocese and the Order.

10. Bishop Hanrahan sought funding for the work, largely through the Maurice Carter Trust. Later, funding for staff would come through a variety of State and community grants.

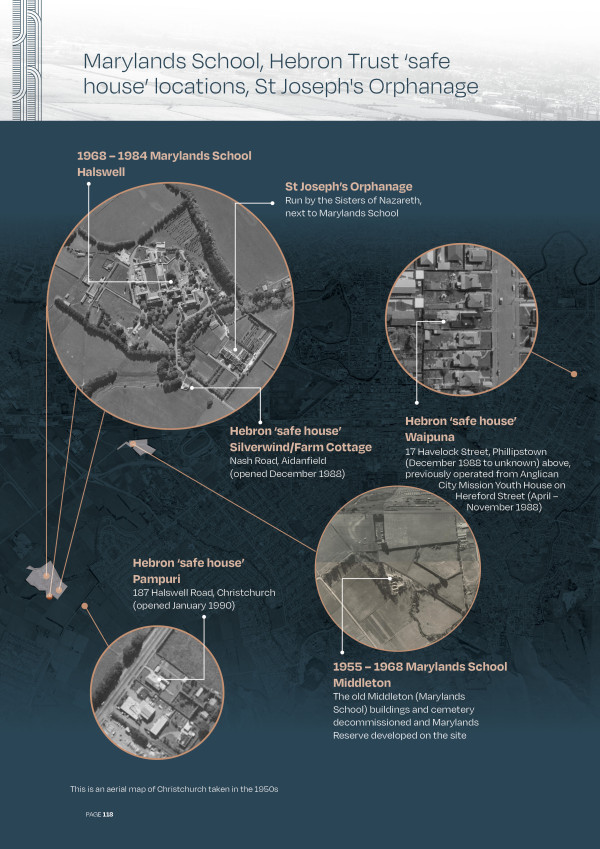

11. From 1988, Brother McGrath’s activities expanded.[213] A short-term accommodation refuge called ‘Waipuna’ opened in April 1988, located on Hereford Street next to the City Mission shelter, then moved to Havelock Street, Linwood in December 1988. By June 1989 it had five paid staff. Waipuna was intended to provide ‘time-out’ for young people, a break for the young person’s family and a chance to plan the next step.[214] Many clients were self-referred.[215]

12. Brother McGrath ran the refuge and lived on site. The Order could not explain why he was permitted to reside outside the local religious monastery. In living outside the monastery, Brother McGrath operated without any supervision or oversight by Church leaders.

13. In a letter from Brother Timothy Boxall to the Provincial Brother Pius Hornby confirming financial support for Brother McGrath’s activities, he indicated concerns about Brother McGrath’s lack of supervision and the fact he was putting himself in dangerous situations:

“My concern is Bernard [McGrath] and his almost complete isolation from the community. He comes and goes and mostly for a specific reason doing his washing, checking his answering service, but never stops or sleeps here or attends mass or any community exercise. We really do not know any of his movements and only expect him when we see him and in all honesty he is often forgotten about.

[Brother] Berchmans only mentioned how Bernard was putting himself into vulnerable situations, by bringing young girls to the monastery in the evenings. I am sure he sees no danger as he is so wrapped up in his work and doesn’t see the dangers. Maybe it is his intention to set up house in his new location, but this was never anticipated when we voted for the house.

I am not sure of the answer but feel someone should perhaps discuss his intentions and his future with him. I would like this done by yourself or a councillor as I am not confident in dealing with this delicate subject.”[216]

14. We have not seen any evidence of any action taken as a result of the concerns Brother Boxall raised.

15. As young people moved through Waipuna, staff became conscious of a need for a ‘half-way’ home where more living skills could be learned before the young people moved into their own flats.[217] In December 1988, expansion continued and a new ‘safe house’, called alternatively Silverwind or Farm Cottage, was opened in Christchurch.[218] It was established specifically for women, with the aims of giving young women time out from their families, time to prepare for a flatting situation, ‘straight’ time before entering a treatment programme, or time to transition back into society after discharge from a treatment programme or institutional care.[219]

16. While there is some uncertainty regarding the extent of services that were provided through (what became in 1989) Hebron Trust over the period from 1986 to 1992, the organisation ran refuges and drop-in centres for youth, and also ran separate safe-houses for women and men. Brother McGrath was primarily responsible at an operational level but there is evidence he provided reports to the Bishop and the Order. It did not have a name until April 1989, when Brother McGrath chose the name ‘Hebron’.[220] In January 1990, Hebron Trust expanded further, establishing another ‘safe house’, this time for young men, called Pampuri House, also in Christchurch. From May 1990, Hebron Trust had also established additional drop-in centres aimed at street kids.

Ka whakaaetia te noho a te Tarati o Hebron hei ratonga mō te Kāwanatanga

Hebron Trust approved as State service provider

17. On 2 May 1990, Hebron Trust was approved by the State as a service provider. Records show that the initial application was declined by the Department of Social Welfare, due to the lack of confidence in Hebron Trust being able to deliver services on the scale proposed, and the effectiveness of services proposed. Hebron Trust was subsequently approved but no documents were located as to why the application was approved.[221]

18. The Community Funding Agency in the Department of Social Welfare was established in 1992. Hebron Trust received conditional approval as a Child and Family Support Service under section 396 of the Children, Young Persons and Their Families Act 1989 on 20 October 1992.[222]

19. The agency’s Procedures Handbook required that no person with any conviction for violence against a person (including sexual violations) and/or dishonesty was to be involved with the care of children and young people. The procedures used for recruiting staff and ensuring their suitability were described with documentary proof produced and had to be forwarded to the agency to file.

20. The agency assessed Hebron Trust against the Standards of Approval annually.[223]

![A picture of a quote that says “[Brother] Berchmans only mentioned how Bernard was putting himself into vulnerable situations, by bringing young girls to the monastery in the evenings. I am sure he sees no danger as he is so wrapped up in his work and doesn’t see the dangers. Maybe it is his intention to set up house in his new location, but this was never anticipated when we voted for the house”. - Letter from Prior Br Boxall to Provincial Brother Pius Hornby](/assets/page-banners/Stolen-Lives/BR__ResizedImageWzYwMCw0MzBd.jpg)

Kō wai te hunga i taurimatia e te Tarati o Hebron Who was cared for by Hebron Trust

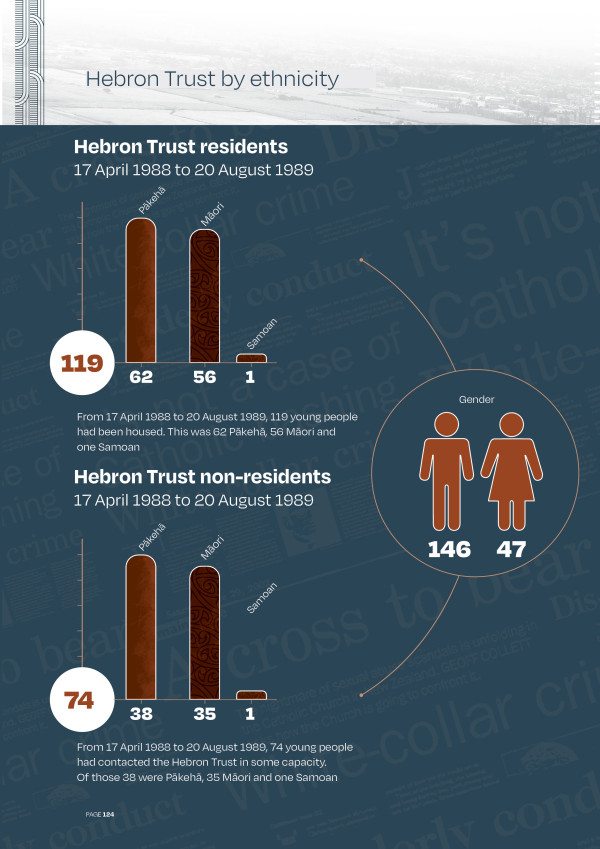

21. Information is limited on who passed through Hebron Trust facilities and why they were there. The Order does not have a record of the numbers of youth that were cared for by Hebron Trust. The Inquiry has received some information from the Order about Hebron Trust residents for the period 1988 to 1990, which gives a snapshot of the numbers passing through and the gender and ethnicity of those in care. [224]

22. We know that Hebron Trust residents were usually teenagers, although the Inquiry has heard from Hebron Trust survivors who were as young as eight[225] and ten years old.[226]

23. The total number of complaints of abuse relating to Māori, Pacific peoples and disabled people is unknown because that “data has never specifically been collected by the [o]rder”.[227]

24. According to the instructions of Hebron’s Waipuna refuge, when a child arrived at any Hebron Trust facilities, the staff member took their name and contacted their parents, the Department of Social Welfare (prior to the establishment of the Children, Young Persons and their Families Service) or police, to let them know the child was there.[228]

25. According to survivor Mr EU, when he sought redress from the Order in relation to abuse at Hebron Trust, he was told “there was a lack of contemporaneous records to support the claim”.[229]

26. From 17 April 1988 to 20 August 1989, 119 young people had been housed, 64 of whom had returned for a further placement.[230] The ethnicity of these young people was 62 Pākeha, 56 Māori and one Samoan.[231] Figures 3 and 4 illustrate this.

27. From 17 April 1988 to 13 July 1990, 331 young people had contacted Hebron Trust in some capacity. Of those, 153 were Māori, 168 were Pākehā, seven were Samoan, one was Tongan, one Greek and one Lebanese. There were 240 males and 91 females.[232]

28. From this data, it appears there were approximately equal numbers of Māori and Pākehā young people in care at Hebron Trust and more young males than females. The number of Māori were disproportionate to the number of Māori in Christchurch at the time.[233]

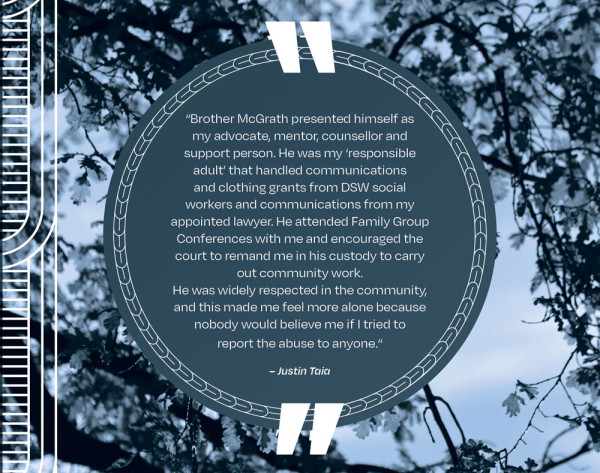

29. Based on Hebron Trust statistics collected for the period mentioned above, it seems that the number of young people cared for by Hebron Trust increased signficantly from that point. In a letter to Bishop Basil Meeking in 1992, Brother Bernard McGrath thanked the Bishop for allowing Hebron Trust to distribute a fundraising pamphlet, and noted that 680 youths were cared for within an 18-month period:

“During the eighteen months up till 31st December 1991, 680 young people passed through Waipuna, Hebron’s youth refuge in Linwood.”[234]

30. The pamphlet was published with the Order projecting that a high number of young people would be cared for by Hebron Trust, the pamphlet read:

“This year, just to cope with the programme we are committed to, is going to cost us approximately $443,700. This will help over 700 kids directly and indirectly. It sounds a lot of money but when we take into account food, power, programme costs, administrative costs, salaries and general running expenses – well it doesn’t go far.”[235]

Te ara i takahia e te hunga taiohi ki te taurimatanga a te Tarati o Hebron

Pathways of young people to Hebron Trust care

31. Young people came into the care of Hebron Trust (and its predecessor organisations) through several different pathways. Between 17 April 1988 and 20 August 1989, 80 percent of residents and non-residents were self-referred, and 20 percent referred by an agency.[236] It is unclear, however, what the term “self-referred” covers. For example, it may include young people who ran away from other family or other institutions and had nowhere else to go, family members suggesting the young person go into the care of the Hebron Trust, or Brother McGrath himself picking up young people from the street and taking them in, or possibly a combination approach.

32. We have heard from survivors who were referred to Hebron Trust through youth justice placements. Lee Robinson who provided legal service to the Catholic Church and the Order in the 1990s and 2000s, said that although unable to exactly quantify how often it occurred, “Judges would frequently refer youth to receive services and guidance from the Hebron Trust.”[237] Mr Robinson stated that “this was presumably because of the Trust’s reputation and Brother McGrath’s standing in the community at that time.”[238] There didn’t appear to be a formal assessment of the appropriateness of these referrals.

33. Lew Corbett, a retired police officer, said police would frequently place ‘street kids’ with Hebron Trust:

“Before my investigation into Bernard McGrath, I was aware of who he was through my dealings with him in the police. When working in and around Christchurch, it was common to uplift children who were street kids or runaways and deliver them to the Hebron Trust where it was believed they would be supported.

Quite often young persons from the youth court, who had been in trouble, were either remanded or directed by the courts to the custody of the Hebron Trust run by McGrath.”[239]

34. We have also heard from survivors who had been sexually abused by Brother McGrath previously, when they were living on the streets, and Brother McGrath

supplied them with alcohol, money and drugs, and who were then later placed at Hebron Trust as part of community work, only to be sexually abused again.

35. Mr GJ told us he went through a family group conference and was placed at Hebron Trust for breaking into his school at age 13. He realised that Brother McGrath was the same man that supplied him with drugs and sexually abused him when Mr GJ was nine or ten years old, a vulnerable child who spent time in the local park to escape his family violence.[240]

36. Survivors were also placed into Hebron Trust’s care through their own families or whānau, including where family members adhered to other faiths such as the Salvation Army.[241]

37. Mr EU’s mother worked for the Order, and asked Brother McGrath to help with her two sons’ behavioural problems. Brother McGrath visited Mr EU in his family home and on the Marylands school grounds, where Brother McGrath sexually abused him. Several years later Mr EU was sent to Hebron Trust while undergoing community work.

“On one occasion, at the end of community work, my mother took me to the chapel at the St John of God Hospital. Brother McGrath was there. My mother knew that Brother McGrath ran a house that cared for troubled boys. My mother thought it might be good for me to have two weeks break from the family, staying with Brother McGrath.”[242]

38. For the ‘street kid’ drop-in centres run by Hebron Trust, the young person initiated contact. There is no information about what led those young people to connect with Hebron. There is also no information on their ethnicity or ages.

39. Mr CA told us:

“All the street kids knew that Brother Bernard was someone who would give us food and money, if we asked for it.”[243]

Ngā ara Māori ki te Tarati o Hebron

Māori pathways to Hebron Trust

40. The Order has limited records of the number of Māori who attended Hebron Trust. The Inquiry itself also has limited firsthand survivor evidence from Māori and their experiences at Hebron Trust.

41. In the early 1990s at the age of 15, Hanz Freller, Māori and Austrian, whose immediate family had broken down, was placed at Hebron Trust’s Pampuri home, in Christchurch, after his grandparents could no longer care for him. He told us:

“You know, my mind starting to sort of tick, why is this person asking me to live in this house because I’m not a street kid, I haven’t been naughty enough to go to court.”[244]

42. Justin Taia told the Inquiry that he was spending time with the ‘street kids’ and that is how he first came into contact with Brother McGrath. He said that Brother McGrath groomed him and abused him for four years.[245]

Ngā ara a ngā tāngata o Te Moana nui a Kiwa ki te Tarati o Hebron

Pacific peoples’ pathways to Hebron Trust

43. The Order has no official records of the number of Pacific persons who attended Hebron Trust. The Inquiry itself also has limited direct survivor evidence from Pacific people and their experiences at Hebron Trust.

44. Mr EP told us his father was physically abusive towards his mother. His father left when Mr EP was young and his mother was regularly absent. Mr EP’s brother was placed in foster care. Mr EP was aged between five and eight years old when he was sexually abused by Brother McGrath while visiting Hebron Trust facilities with his brother.

“When I was growing up, [my brother] used to go to Hebron House. It was quite close to our home, and I think [my brother] was sent there to do some community work, as he had been in trouble with the police.”[246]

45. A client of Cooper Legal, of Palagi and Tongan descent, lived on and off the streets between 1986 and 1989. She recalls Brother McGrath being a constant presence on the streets. He would come around in a van, collecting young people and taking them back to Hebron Trust. She said that he hated the girls. The boys would sneak her and other girls in late at night. They would use Hebron Trust as a warm place to sleep over night. She had an official placement at Waipuna for about two and a half weeks in approximately 1988. Her Department of Social Welfare file records this as being “rescued” from the “street kid scene by Brother McGrath”. She later had community work placements through Hebron Trust.[247]

Ngā Whakakitenga: Tarati o Hebron

Findings: Hebron Trust

46. The Royal Commission finds:

a. During the earlier years of its existence, Hebron Trust was informal, largely unregulated and its operations were mostly unmonitored by the Order or by the Bishop of Christchurch.

b. Police and the courts often referred rangatahi to Hebron Trust to receive services and guidance but without proper assessment as to the appropriateness of this placement. Many of the rangatahi were homeless, were in the justice system and suffered from substance abuse issues. The number of rangatahi Māori in the care of Hebron Trust was disproportionate to the population of Christchurch.

[202] Schedule of St John of God two-day meeting, A programme to discern the future of our Order in New Zealand – 17 to 18 January 1986, CTH0016720 (no date), p 1; Letter from Brother Anthony Leahy to Bishop Hanrahan, seeking guidance about the order’s presence and possible contribution to New Zealand, CTH0016721 (26 November 1985).

[203] Transcript of opening statement of the Bishops and Congregational Leaders of the Catholic Church in Aotearoa from the Marylands School public hearing, TRN0000411, (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 09 February 2022) p 5.

[204] Hebron Trust Statistics, 17 April 1988 to 13 July 1990, CTH0012268, Hebron Trust (20 August 1989), p 45.

[205] Statement by Catholic Social Services, regarding the Hebron Youth Trust, CTH0012268 (14 June 1989), p 25.

[206] Evaluation: Report to the Christchurch Community, Report to the Provincial, CTH0012268 (13 February 1988), pp 59 – 69.

[207] Te Rōpū Tautoko Marylands Briefing Paper 2: Summary of events relating to the Hebron Trust, MSC0007268 (23 July 2021), para 9.

[208] Proposal to Bishop Hanrahan and Brother Hornby regarding “street kids” from Brother McGrath, CTH0016723 (2 November 1986), p 3.

[209] Proposal to Bishop Hanrahan and Brother Hornby regarding “street kids” from Brother McGrath, CTH0016723, p 3.

[210] Letter from Brother Hornby (Provincial) to Bernard McGrath regarding McGrath’s report, CTH0012268 (8 December 1986) p 281.

[211] Te Roopu Awhina was an existing venture between Catholic Social Services, the Anglican City Mission and Moranga House.

[212] Catholic Social Services is an agency of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Christchurch.

[213] Statement by Catholic Social Services, CTH0012268, p 27.

[214] Statement by Catholic Social Services, CTH0012268, p 207.

[215] Information about Waipuna Youth Refuge, Hebron Trust, CTH0012268 (no date) p 378.

[216] Letter from Brother Boxall to Brother Pius, CTH0012032_00002 (31 August 1988), p 3-4.

[217] Hebron Youth Trust, CTH0012268 (Catholic Social Services, 14 June 1989), p 27.

[218] Te Rōpū Tautoko Marylands Briefing Paper 2, MSC0007268, para 26, See also: Hebron Trust Statistics, 17 April 1988 to 13 July 1990, CTH0012268 (Hebron Trust, 20 August 1989), pp 46–47; Brief History of the Hebron Trust, 1986 to 1995, CTH0015131, p 5.

[219] Information about Farm Cottage / Pampuri, Hebron Trust, CTH0012268 (undated), p 390.

[220] Te Rōpū Tautoko Marylands Briefing Paper 2, MSC0007268, para 27.

[221] Brief of evidence of Peter Galvin for Oranga Tamariki, WITN1056001, para 27.

[222] Brief of evidence of Peter Galvin for Oranga Tamariki, WITN1056001, paras 27, 29.

[223] Brief of evidence of Peter Galvin for Oranga Tamariki, WITN1056001, para 29.

[224] Hebron Trust Statistics, CTH0012268, p 46–47.

[225] Witness statement of Mr EP, WITN0727001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 16 October 2021), para 16.

[226] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, paras 288.

[227] Te Rōpū Tautoko Marylands Briefing Paper 6: Nature and extent of abuse in the care of the Hebron Trust, as amended on 17 December 2021, CTH0020744, p 3.

[228] Hebron Trust Statistics, CTH0012268, p 46-47.

[229] Witness statement of Mr EU, WITN0709001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 12 October 2021), para 83.

[230] Hebron Trust Statistics, CTH0012268, p 46-47.

[231] Of the total 193 young people, (119 were residents and 74 were non-residents) 47 were female and 146 were male.

[232] Hebron Trust Statistics, CTH0012268, p 307.

[233] Historically, the population of Māori in the South Island has been comparatively smaller than that of the North Island. Census data from 1951 shows that of the 115,676 Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand, only 4,000 are recorded as living in the South Island. This trend continues, five years later in 1956 of the total 137,151 Māori, only 5,200 were living in the South Island.

[234] Letter from Brother McGrath to Bishop Meeking, regarding the Hebron Trust‘s strategic plan, CTH0016761, (4 March 1992) p 1.

[235] Hebron Community Trust Pamphlet, CTH0012268, p 2.

[236] Hebron Trust Statistics, CTH0012268, pp 46–47.

[237] Witness statement of Lee Robinson, WITN0836001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 23 July 2021), para 69.

[238] Witness statement of Lee Robinson, WITN0836001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 23 July 2021), para 69.

[239] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146001, paras 3.19, 3.20.

[240] Witness statement of Mr GJ, WITN0731001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 January 2021), paras 33–35, 43–46.

[241] Witness statement of Mr IS, WITN0972001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 30 November 2021), paras 3.10 and 3.11.

[242] Witness statement of Mr EU, WITN0709001, paras 3–10, 30.

[243] Witness statement of Mr CA, WITN0721001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 17 September 2021), para 91.

[244] Transcript of evidence of Hanz Freller from the Marylands School public hearing, TRN0000413 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 11 February 2021), p 28 pp 26.

[245] Witness statement of Justin Taia, WITN0759001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 8 November 2022), para 56.

[246] Witness statement of Mr EP, WITN0727001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 16 October 2021), para 13.

[247] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, paras 734–738.