Chapter 6: The frameworks underpinning the Inquiry's work Upoko 6: Ngā pou tarāwaho e taunaki nei i ngā mahi a te Kōmihana

197. The Inquiry’s Terms of Reference required it to consider the frameworks that would underpin its work. The Terms of Reference explicitly directed the Inquiry to ensure it was underpinned by te Tiriti o Waitangi. The Terms of Reference also directed the Inquiry to recognise and focus on the experiences of groups who have been disproportionately represented in care and disproportionately suffered abuse in care, including Māori, Pacific Peoples, and disabled people and people who experience mental distress).

198. Some of the frameworks used are recognised as having formal standing in international and domestic law (such as te Tiriti o Waitangi and human rights). Other frameworks outline core values and worldviews held by groups and communities. A person and their loved ones’ experience of abuse and neglect, the impact of the abuse and how these interact, can differ depending on their values and worldview.

199. This chapter describes the following frameworks and how they guided the Inquiry’s work:

- te Tiriti o Waitangi

- ngā tikanga me te ao Māori

- human rights

- Deaf, disability and mental distress framework

- Pacific values framework.

200. This chapter sets out other concepts – intersectionality, co-occurring abuse and cumulative abuse – that guided the Inquiry’s understanding of the nature, extent and impacts of abuse and neglect, and of the factors that contributed to neglect and abuse in State and faith-based care.

201. The descriptions of these frameworks and concepts explain what has guided the Inquiry’s analysis and considerations. They are not intended to be a comprehensive analysis. The Inquiry acknowledges the tensions between frameworks based on individual rights, such as human rights, and those that reflect collective responsibilities, such as tikanga Māori and Pacific values.

Tā te Kōmihana whakatinana i ngā pou tarāwaho

How the Inquiry used these frameworks

202. The Inquiry used these frameworks to analyse evidence and identify where these frameworks, values and worldviews were breached or transgressed. This enabled the Inquiry to identify the nature, extent and impact of abuse and neglect, factors contributing to the abuse and neglect, and what needs to change in the future.

203. In identifying and applying these frameworks, the Inquiry noticed a few differences but many more commonalities. For example, most of the frameworks place value on:

- the need for participation by people in decisions that affect them

- the sanctity of childhood

- respect for familial relationships

- respect and equity for individuals within the family unit

- inherent human dignity

- maintaining relationships between individuals and communities

- empowerment of whānau and communities

- protection from harm.

Ko te Tiriti o Waitangi te tūāpapa o te Pakirehua

The Inquiry was underpinned by te Tiriti o Waitangi

204. The Terms of Reference required the Inquiry to be underpinned by te Tiriti o Waitangi and its principles.[121] The Inquiry set out its general approach to te Tiriti o Waitangi in some of the interim reports.[122]

205. Guided by the intention to recognise te Tiriti o Waitangi and its principles, as well as the status of iwi and Māori under te Tiriti o Waitangi,[123] the Inquiry has sought to centre te Tiriti o Waitangi in all its work. This includes using te Tiriti o Waitangi as:[124]

- a primary framework and lens for this report

- a standard against which action or omission (of the Crown and faith-based care institutions) must be assessed

- a pillar that guides the recommendations.

206. The status of te Tiriti o Waitangi in Aotearoa New Zealand’s legal system has evolved over time.[125] No longer a “simple nullity”,[126] te Tiriti o Waitangi is now recognised as “of the greatest constitutional importance”.[127] If it is included in legislation, it has direct legal force and effect. Where it is not explicitly mentioned, courts have found that te Tiriti o Waitangi can be relevant to interpretation of the statute and the development of the common law. The courts have adopted a general presumption that Parliament intended to legislate in terms consistent with te Tiriti o Waitangi.[128] In the context of legislation dealing with the care of children, the court has said:

“We are of the view that since the Treaty of Waitangi was designed to have general application, that general application must colour all matters to which it has relevance, whether public or private … We also take the view that the familial organisation of one of the peoples a party to the Treaty, must be seen as one of the taonga, the preservation of which is contemplated. Accordingly, we take the view that all Acts dealing with the status, future, and control of children are to be interpreted as coloured by the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. Family organisation may be said to be included among those things which the Treaty was intended to preserve and protect.”[129]

207. The Inquiry reviewed the significant body of jurisprudence that the Waitangi Tribunal and the courts have developed over the last 40 years to apply te Tiriti o Waitangi and its principles in the context of its work. While there are some well-established te Tiriti o Waitangi principles, the interpretation and articulation of these principles has developed over time.[130] The Inquiry placed weight on recent descriptions of te Tiriti o Waitangi principles by the Waitangi Tribunal. This is consistent with the courts’ approach of considering the opinion of the Waitangi Tribunal that te Tiriti o Waitangi is always speaking.[131]

208. The Inquiry was aware of the significant debate over the differences between te Tiriti o Waitangi and the Treaty of Waitangi.[132] Talking about the principles can be controversial, particularly when they are interpreted in a way that lessens or undermines guarantees in the reo Māori text.[133]

209. The Terms of Reference refer to “te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi and its principles”. The Inquiry’s approach was to take meaning from the text, intent and circumstances surrounding the signing of te Tiriti o Waitangi. The principles cannot be separated from, and necessarily include, the articles and language of te Tiriti o Waitangi itself.[134] The Supreme Court has demonstrated a willingness to refer to and uphold the articles.[135] The Waitangi Tribunal has found that te Tiriti o Waitangi principles must be based in the actual agreement entered in 1840 between rangatira and the Crown.[136] Recent Cabinet Office guidance has noted that “while the courts and previous guidance have developed and focused on principles of the Treaty, this guidance takes the texts of the Treaty as its focus”.[137]

Ngā mātāpono o te Tiriti o Waitangi i whakamahia i te Pakirehua

Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles used in the Inquiry

210. Considering the text of te Tiriti o Waitangi, the Inquiry adopted the following principles:

- tino rangatiratanga

- kāwanatanga

- partnership

- active protection

- options

- equity and equal treatment

- good government

- redress.

Tino rangatiratanga

211. Te Tiriti o Waitangi gives Māori the right to autonomy and self-government, and to manage the full range of their affairs in accordance with their tikanga.[138] Te Tiriti o Waitangi guarantees Māori the rights and responsibilities that their communities have had for generations.[139] Te Tiriti o Waitangi guarantees ongoing full authority of Māori over their kāinga (home, residence, village, homeland) encompassing the rights to continue to organise and live as Māori, to cultural continuity where whanaungatanga is strengthened and restored, and to care for and raise the next generation.[140]

Kāwanatanga

212. Te Tiriti o Waitangi gave the Crown, through the new kāwana (governor), the right to exercise authority over British subjects, keep the peace and protect Māori interests. Te Tiriti o Waitangi did not give the Crown a supreme and unilateral right to make and enforce laws over Māori. Crown power is constrained. The Crown has a duty to foster tino rangatiratanga, not undermine it, and to ensure its laws and policies are just, fair, and equitable and to adequately give effect to te Tiriti o Waitangi rights and guarantees.[141]

Partnership

213. Te Tiriti o Waitangi envisages that the Crown and Māori are equals with different roles and spheres of influence.[142] Partnership requires the co-operation of both the Crown and Māori to agree to their respective areas of authority and influence, and to act honourably and in good faith towards each other. The Crown is not to decide what Māori interests are or what the sphere of tino rangatiratanga includes. The Crown’s duty is to engage actively (rather than consult) with Māori and to ensure shared decision-making with Māori.

Active protection

214. The Crown must actively protect Māori rights and interests, including tino rangatiratanga. This includes rights relating to the wellbeing of Māori in care. The Crown cannot cause harm or stand by while harm is done. The active protection of tino rangatiratanga is a duty on the Crown that comes from its obligation to restore balance to a relationship that became unbalanced.[143] Because the Crown expanded its sphere of authority beyond the bounds originally understood by Māori who signed te Tiriti o Waitangi, the duty of action protection is heightened so long as the imbalance remains.[144]

Options

215. Māori have the right to continue to govern themselves along customary lines, or to engage with the developing settler and modern society, or a combination of both. This principle derives from the guarantee to Māori of both tino rangatiratanga in Article 2 and the rights and privileges of British citizenship under Article 3.[145] The principle of options, therefore, follows on from the principles of partnership, active protection, and equity and protects Māori in their right to continue their way of life according to their indigenous traditions and worldview while participating in non-Māori society and culture, as they wish.[146] The Crown must adequately protect the availability and viability of kaupapa Māori solutions in the social sector as well as mainstream services in such a way that Māori are not disadvantaged by their choice.[147]

Equity and equal treatment

216. Te Tiriti o Waitangi guarantees Māori equitable treatment and citizenship rights and privileges, and the Crown has a duty to actively promote and support both.[148] The principles of equity and equal treatment also protect Māori from discrimination. Equity requires the Crown to focus attention and resources to address the social, cultural, and economic needs and aspirations of Māori. The Crown must actively address inequities experienced by Māori, and this obligation is heightened if inequities are especially stark. At its heart, satisfying the principle of equity requires fair treatment, not just equal treatment. This is a duty to be undertaken in partnership with Māori.

Good government

217. The principle of good government, alongside the principles of equity and equal treatment and options, derive from Article 3. These are all necessary components of te Tiriti o Waitangi assurance to Māori of equal citizenship rights. It requires the Crown to keep its own laws and not to act outside of the law. It also stresses that the Crown’s actions must be just and fair.

Redress

218. If the Crown acts in excess of its kāwanatanga powers or breaches the terms of te Tiriti o Waitangi in any other way by act of omission that results in prejudice, the Crown should provide compensation.[149] This includes breaches relating to the removal of people from their communities, the design and delivery of care, and the impacts on Māori as individuals, and their communities, and culture. In terms of the form of redress, the Waitangi Tribunal has stated that this involves the means for economic and social development looking forward, and the means to ensure the survival and wellbeing of tribal taonga, including language, culture, customs, lands and other resources.[150] Redress should be based upon a restorative approach, with its purpose being to restore iwi or hapū rangatiratanga over their property or taonga where the parties agree.[151]

Tā te Kōmihana whakauru i ēnei mātāpono

How the Inquiry applied these principles

219. While the Inquiry considered that the application of te Tiriti o Waitangi was always contextually dependent, te Tiriti o Waitangi and its principles were applied to the provision of care by the State and faith-based institutions.

220. The Crown’s obligations in respect of care provided by the State stem directly from being a party and signatory to te Tiriti o Waitangi. When the Crown delegates responsibilities to State organisations (such as Oranga Tamariki or the Ministry of Health), the Crown must ensure those institutions recognise Māori rights and values and act in accordance with the Crown’s te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations.[152] This is consistent with the principle of active protection. The Crown’s obligations therefore apply to all State organisations that provide care.

221. Although faith-based institutions and indirect care providers are not te Tiriti o Waitangi partners, the Inquiry took the approach that:

- legislation may require faith-based institutions and indirect care providers to act consistently with te Tiriti o Waitangi [153]

- te Tiriti o Waitangi influences the interpretation of all legislation dealing with Māori, and therefore may impact on faith-based institutions and indirect care providers when they care for tamariki, rangatahi and pakeke Māori[154]

- if faith-based institutions and indirect care providers made their own commitments to te Tiriti o Waitangi (for example, in governing documents or public statements), they may be held accountable to meet those commitments.[155]

222. The Inquiry considered the abuse and neglect of Māori survivors in care through a Tiriti o Waitangi lens. This meant identifying when the State and faith-based institutions failed to uphold their obligations and commitments under te Tiriti o Waitangi and its principles, and how this affected Māori survivors. Failures could include, for example:

- a failure to prevent harm to tamariki, rangatahi and pakeke Māori (the principle of active protection), or

- a failure to protect tamariki, rangatahi and pakeke Māori in care from discrimination (the principle of equity and equal treatment).

223. Part 5 describes the impacts of abuse and neglect in care, including how failures to uphold te Tiriti o Waitangi and its principles have affected Māori survivors. Part 7 sets out the Inquiry’s concluding observations about how the State and faith-based institutions failed to uphold their obligations and commitments under te Tiriti o Waitangi and its principles.

Ngā tikanga me te ao Māori

Concepts and te ao Māori

224. In addition to directing that the Inquiry be underpinned by te Tiriti o Waitangi, the Terms of Reference directed the Inquiry to give appropriate recognition to Māori interests, acknowledging that Māori have been disproportionately represented in State and faith-based care.[156] The Inquiry acknowledges that Māori survivors have disproportionately experienced abuse and neglect in care.

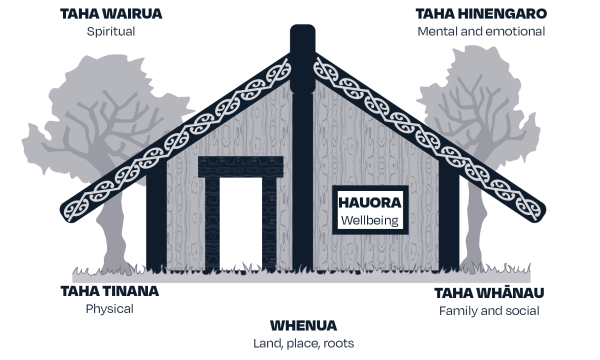

225. In He Purapura Ora, he Māra Tipu, the Inquiry discussed Te Whare Tapa Whā, a Māori health and wellbeing model developed by Tā Mason Durie.[157] Te Whare Tapa Whā is a model that many survivors of abuse and neglect in care are familiar with, and is grounded in the tikanga concepts outlined below. It uses four dimensions – te taha wairua (spiritual health), te tana hinengaro (mental and emotional wellbeing), te taha tinana (physical health) and te taha whānau (family health) – to conceptualise Māori health and wellbeing as four walls of a wharenui.

226. This section sets out te ao Māori foundational values and beliefs, building on Te Whare Tapa Whā and other Māori wellbeing concepts discussed in He Purapura Ora, he Māra Tipu.[158] These values and beliefs are: te ao Māori, whakapapa, mana, mana motuhake, tapu, mauri, wairua and hauora. The tikanga relating to behaviours and practices about the care and treatment of people and things include: whanaungatanga, manaakitanga, atawhaitanga, tauwhirotanga, kaitiakitanga, utu, muru, ea and tūkino. This section was informed by the expertise of the Inquiry’s Pou Tikanga group.

227. There is a wide range of interpretations of tikanga, key Māori concepts and values, with much attention given to the definitions and interpretations over many generations. These descriptions reflect what has guided the Inquiry’s analysis and investigations. They are not intended to be a comprehensive analysis of the terms and concepts used.

228. The Inquiry chose to draw on these tikanga Māori (Māori customary practices or behaviours) and whakaaro Māori (Māori worldview or philosophy) to examine abuse and neglect in care because a disproportionate number of survivors are Māori and, for many, a meaningful response to the tūkino – abuse, harm and trauma – inflicted and suffered can only occur on Māori terms. The Inquiry learned that tikanga Māori concepts resonated with many non-Māori survivors, and with their views about the impacts of abuse and neglect and the actions that were needed to restore their lives. Working in accordance with tikanga Māori, the Inquiry acknowledges that everyone has their own mana, and every survivor has their own experiences.

Te ao Māori – he ao tūhonohono

Te ao Māori – a relational world

229. Te ao Māori can be explained as the Māori worldview (the way Māori see the world through a Māori cultural lens) and the cultural world that Māori live in and operate in. In the context of this Inquiry, when survivors talked about being dislocated and isolated from their Māori culture, they were often referring to both these contexts. Dislocation and isolation from the Māori worldview result from an inability to access the cultural knowledge that would support an understanding and centralising of te ao Māori in their lives. Disenfranchisement from the Māori cultural world comes from not being able to engage and participate in the cultural life of whānau, hapū and iwi.

230. The Inquiry does not intend to glorify or romanticise Māori culture or to present a view that all transgressions of Māori culture and values experienced by survivors were solely at the hands of the State and faith-based institutions. Many Māori survivors recognised their abuse as starting with their own whānau in their own communities, which was the pathway into State care.

231. There are examples of abuse, or actions that were deemed inappropriate and contrary to common values, passed down through traditional narratives in pūrākau, waiata and whakataukī. What is clear from these narratives is that the abuse of tamariki and whānau members was not something condoned or supported in traditional Māori society, and that abuse carried consequences condemning those actions.

232. Te ao Māori is guided by the understanding and operation of tikanga Māori. The term tikanga can be translated as a custom, habit, rule or code of behaviour. Tikanga are the primary customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context in which they operate or apply to. They are based on shared, commonly held beliefs and values that are passed on intergenerationally and guide behaviours and practices. Importantly in this context, tikanga set expectations about what is right and just, and what is wrong and should be avoided. When followed and adhered to, tikanga helps keep people and things safe.

233. The way tikanga Māori manifests can vary between different whānau, hapū and iwi but the values and principles underlying tikanga are relatively consistent.[159] This is because those values and principles come from common elements of a shared understanding of te ao Māori, origins and histories, the interrelationships between people, land and the environment, and expectations about the way people interact with that world and each other. Where there are differences, the foundational values become the basis upon which tikanga are negotiated between collectives and individuals.

234. The hauora of an individual in te ao Māori is intimately tied to the hauora of their collective. The care, protection and nurturing of a person’s whole wellbeing was the responsibility of the collective. Negative impacts on the mana, tapu, mauri, wairua and rangatiratanga of an individual therefore need to be seen in the context of the relational influence on the mana, tapu, mauri, wairua and rangatiratanga of the wider whānau, hapū and iwi.

235. The collective impact of wrongdoing on a whānau, hapū or iwi was mirrored by a traditional understanding of collective responsibilities for the care and protection of the members. The ownership of the violation was seen to sit not only with the individual, but with all of those deemed to have cultural and social influence and control over that individual. This is exemplified by the whakataukī “Hē o te kotahi, hē o te katoa” – “the wrongs of one are the wrongs of us all”. This saying would be used when referring to the actions of an individual that would bring the mana of the collective into disrepute. Because of this view, punishment for a violation would not be confined to an individual, but could be extended to their whānau, hapū or iwi.

236. When the Inquiry considered these concepts in relation to survivors’ experiences, it was important to acknowledge the impact and reach of that harm on the wider collectives of whānau and hapū.

Ngā tikanga Māori

237. The values and beliefs discussed below are:

- whakapapa

- mana

- mana motuhake

- tapu

- mauri

- wairua

- hauora.

Whakapapa

238. Whakapapa can be translated as genealogy, lineage or descent. Central to an understanding of the Māori worldview is the belief that everything, both tangible and intangible, has whakapapa. It is central to all Māori practices and is the basis from which all understanding can be derived. This includes the interpersonal attachments to whānau, hapū, iwi and whakapapa and the attachments to whenua and wairua.[160] Whakapapa allows the characteristics and qualities of all things and their interrelationships to be understood.[161]

239. Whakapapa is an essential element of belonging, identity and how Māori view and approach the world. It is an attribute Māori are born with and provides them with their identity within their whānau, hapū and iwi. It connects them to their tupuna, their atua, and to their tūrangawaewae (a place where an individual, their hapū, and their ancestors stand and belong, and where their mokopuna will belong).[162] It is through whakapapa that individuals are given attributes fundamental to their cultural, physical, and spiritual wellbeing, such as mana, tapu, wairua and mauri.[163] Every Māori is born with these attributes, but not every Māori is aware of them.[164]

240. In te ao Māori great status and value was traditionally placed on the learning of whakapapa so that a person could understand their relationship to the natural world. Whakapapa connects people to the past and the future, to thought and to action, to place and the environment. Such knowledge was essential for the survival of the people and the world they inhabited and formed the foundation of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge).[165] Understanding those relationships and their associated stories resulted in an intimate understanding of associated roles and responsibilities within the Māori world. Knowing whakapapa was important to understand connections between people and in decision-making processes and resolving disputes.

Mana

241. Mana includes power, presence, authority, prestige, reputation, influence and control. Mana is not confined to an individual but belongs to collective groups. Mana does not cease when an individual dies but continues with the whānau, hapū and iwi they belong to.[166]

242. There are three main forms of mana that are relevant to this inquiry: mana atua, mana tūpuna and mana tangata. Mana atua is power that comes from the atua (gods). Mana tūpuna (ancestral mana) is authority and power that is passed down through the generations and is acquired by right of whakapapa. It is therefore inalienable.

243. Mana tangata is personal mana. Mana atua and mana tūpuna are the foundation that mana tangata grows on. Mana tangata reflects a person’s abilities, skills and deeds. It has been described as the “creative and dynamic force that motivates the individual to do better”.[167] Someone’s mana can grow through respect, praise and acknowledgement of their abilities from others. Mana must be respected, and actions that diminish mana result in trouble.[168] How you act and contribute to the world will affect your mana tangata. Likewise, how you are treated by others can have a positive or negative impact on your mana tangata and therefore, your ability to realise your potential, talents and contributions to society.

244. Everyone is born with and possesses mana. The mana of tamariki Māori in traditional Māori society, and the great care and affection given to most tamariki, meant that any action that harmed a tamariti (child) or failed to respect their mana was significant. Mana has collective and individual dimensions that affect each other. If an individual tamariti suffered harm, then depending on the severity, this could be seen to affect the mana of the whānau, hapū , or iwi affected by the tūkino (abuse, harm and trauma). Accordingly, the duty to protect the mana of an individual was understood to be a collective responsibility.

Mana motuhake

245. Mana motuhake is particularly relevant to the Inquiry in two ways:

- The ability of an individual and their whānau, hapū and iwi to make self-determining decisions about the care and protection of themselves and whānau members.

- It speaks to survivor voice and agency in the practices and decisions concerning them. When a person’s mana motuhake is diminished, or removed, this affects their mana tangata and wellbeing.

Tapu

246. Tapu is a sacred life force that supports the mauri (spark of life). It reflects the state of the whole person. It is inseparable from mana and from Māori identity and cultural practices. Tapu is everywhere – within people, places, buildings, things, words – and in all tikanga. Tapu is a person’s most important attribute and is present in the physical body as well as in the spirit. Much like mana, it is inherited and must be protected.[169] A person with great mana was very tapu. There are various ways to interpret and see tapu[170] If someone’s tapu, the most important spiritual attribute of a person, is at a steady state and is safe, their overall physical and psychological state is also [171]

247. Tapu can be extended to someone or something else through physical contact or association. Tapu can also refer to the state of something that has restrictions or prohibitions associated with it. The tikanga governing people’s behaviour would be followed to ensure that the mana and tapu of things were in place. Mahi tūkino, or actions that negatively affect someone’s physical, spiritual or emotional wellbeing, are a transgression of their mana and tapu and are to be avoided.

Mauri

248. Mauri is a life force or vital essence that is present in all living things. It is “a material symbol of a life principle, source of emotions - the essential quality and vitality of a being or entity”.[172] Mauri is interconnected with a person’s wellbeing or state of wellness. Their mauri is affected if their mental, physical, emotional, or cultural health declines or is negatively affected.

249. A person does not control their own mauri beyond their ability to influence and take care of their health and wellbeing, but it can be affected by others and the environment. The outward expression of mauri will be those emotions, behaviours and physical states associated with wellness and life. Therefore, the actions of abuse and neglect and the conditions associated with them can negatively affect an individual’s or collective’s mauri. When the mauri of something has been depleted, it can be restored by addressing the causative factors and providing the proper care and support that enables healing to take place. Strategies to restore the mauri tangata (personal mauri) of survivors will look different depending on their required healing journey.

250. A person dies when their mauri is extinguished.[173] The mauri of survivors of abuse who died before or during this Inquiry has been completely extinguished upon their death. While their health and wellbeing cannot be restored, it is important to recognise the collective impact of the abuse on the mauri of their whānau, hapū, friends and other survivors.

Wairua

251. Wairua is the non-physical spirit or soul of a person. In the Māori worldview, all things, both animate and inanimate, have whakapapa and wairua. A key difference between wairua and mauri is that the wairua is not extinguished at death, but stays in the body until it is released, when it can cross into the spiritual realm and continue forever.

252. There are differing views as to whether a person’s wairua resides within their whole body or in their mind or heart. A person’s wairua is understood to be metaphysical and not necessarily confined to their physical body, which means it can leave the body for short periods, commonly during dreams.

253. Like mauri, a person’s wairua can be affected by external factors such as the actions of others and their environment, as well as internal factors such as feelings and self-esteem. For these reasons, wairua is closely connected to mental wellbeing. All forms of tūkino, whether psychological, emotional, physical, sexual or cultural, have a direct impact on a person’s or a collective’s wairua. The psychological, emotional and cultural concepts of wellbeing associated with wairua, and the physical aspects of wellbeing commonly associated with health, are inextricably connected within a Māori worldview. Thus, if someone receives physical care but not emotional, psychological and cultural care and support, this can still negatively affect their wairua and overall wellbeing, as well as that of their whānau.

Hauora

254. Hauora is generally translated as health or wellness. There are three main aspects of hauora that are relevant to this inquiry:

- hauora hinengaro (mental health and wellbeing)

- hauora tinana (physical health and wellbeing)

- hauora whānau (family health and wellbeing).

255. Understanding the interrelationships between and across the foundational values and beliefs described above is essential to understanding hauora, what contributes to it within a Māori belief system, and how hauora can be affected by tūkino. Wellness also means a state of balance in all spiritual attributes of a person, including their tapu, mana, mauri and wairua.

256. From conception, a person is imbued with all these collective attributes – whakapapa, mana, tapu, mauri and wairua. They interconnect and support each other to create and nourish the foundations of life and wellbeing. If a person’s tapu, mana, wairua or mauri is violated or transgressed, then their whakapapa, mana tangata and rangatiratanga are compromised.

257. The rules and expectations about behaviour and practice, housed in tikanga, were all concerned with ensuring these values were protected and upheld.

Ngā tikanga e pā ana ki te manaakitanga

Ngā tikanga concepts related to care

258. The tikanga relating to behaviours and practices based on the values and beliefs set out above include:

- whanaungatanga

- manaakitanga

- atawhaitanga, tauwhirotanga and kaitiakitanga

- tūkino

- utu and muru

- ea.

259. These are key Māori concepts that speak to the tikanga about the care and treatment of people and things. Inherent in these concepts are expectations about the responsibilities of individuals and collectives to protect, nurture, and provide for other people and the things around them. These concepts individually and collectively illustrate the notion of a duty of care and regard for people and the environment. They are intricately bound to the concepts of mana and tapu.

260. Failure to uphold these tikanga will have a direct impact on the mana of an individual and their whānau or hapū. In such circumstances, the responsibilities and connections usually maintained and nurtured through the practice of whanaungatanga can become frayed and lead to social fragmentation and hostility.

261. The opposite impact occurs when these tikanga are upheld and realised well. This results in an enhancement of the mana of whānau, hapū or iwi, particularly their status, prestige and social cohesion. The mana of whānau, hapū or iwi was considered of paramount value and consideration in Māori society and every effort was put in to attain and maintain mana. Although traditionally mana could be increased through success in war and gaining resources, it was ultimately determined by those acts that contributed to the survival and wellbeing of the people.

Whanaungatanga

262. Whanaungatanga embraces whakapapa and describes the relational connections between people generally translated as kinship or familial relationships. Associated with whanaungatanga are rights and obligations between members of whānau, hapū and iwi that serve to further strengthen kinship bonds. It is a fundamental principle that places obligations on individuals and collective groups to support each other and maintain balance within relationships.[174]

263. Whanaungatanga is the essential principle through which every element is related, tracing common descent down lines of whakapapa.[175] In te ao Māori, identity is expressed through whakapapa that connect people to each other and their ancestors. Understanding interrelationships and associated whanaungatanga is necessary for understanding the health and wellbeing needs of Māori.

Manaakitanga

264. Manaakitanga comes from the word manaaki, which means to support, provide hospitality to and look out for others. It is the overarching concept that includes other tikanga associated with care and nurturing, such as atawhaitanga and tauwhirotanga, and tikanga associated with protection and guardianship of people and things, such as kaitiakitanga.

265. Manaakitanga is the practice of showing care and protection. Practicing manaakitanga means showing respect and generosity, treating others with compassion, looking after people and nurturing relationships. Manaakitanga relates closely to whanaungatanga. All tikanga are underpinned by the high value placed upon manaakitanga.

266. The expression and practice of manaakitanga was arguably one of the key influences and indicators of people’s mana in traditional Māori society and remains so today. When receiving and hosting guests, all effort was invested in showing them the best hospitality and care possible. If guests went away feeling like they had not received manaakitanga from their hosts, the mana of the hosts was negatively affected.

Atawhaitanga, tauwhirotanga and kaitiakitanga

267. Atawhaitanga means the practice of showing atawhai or kindness, compassion, and courtesy to others. Tauwhirotanga means the practice of showing care and kindness, particularly tending to and caring for people who are ill, vulnerable or who need extra support. It was important for all members of the community to embody these tikanga. There were also individuals or groups who held specific responsibilities in relation to the care and protection of other people, places, and things, called kaitiaki. The role of the kaitiaki was to safeguard and protect the things in their care. The practice of doing so is called kaitiakitanga.

Tūkino

268. Tūkino is a central concept that has informed thinking about abuse, harm and trauma.[176] It is a broad term that reflects ill-treatment through violence, abuse, maltreatment, mistreatment, torture and rape. Tūkino expresses the nature and extent of the abuse, harm and trauma that has been inflicted and suffered and implies a transgression of tikanga that is unjust, unfair, violent, destructive, cruel and abusive. Inherent in tūkino is an acknowledgement that pain, trauma, and grief has been inflicted. Where tūkino has occurred, mana is affected.[177]

269. This report refers to three forms of tūkino – patu, whakamamae and whakarere.

- Patu can mean hitting, striking or beating. It can mean physical assault or ill-treatment and the act of killing by violence. Patu can mean non-physical violence, where an action affects a person’s mana or tapu, and therefore their wairua, psychological or emotional state.

- Whakamamae can mean hurt or torture of another person. Like patu, whakamamae can describe both physical and non-physical hurt, such as belittling or racist comments.

- Whakarere can mean neglect, where a person or collective is disregarded or ignored, forsaken, deserted or abandoned. Whakarere can mean neglect of a person’s physical needs, such as shelter and food, and non-physical needs, such as spiritual and emotional needs.

Utu and muru

270. Utu is sometimes referred to as the principle of reciprocity or equivalence and can include compensation or repayment. It is also the term used to describe the cost or price of something, and therefore associated with the cost of an action, transgression, or crime. If tikanga are transgressed and the balance and peace of people and places is negatively affected, there is a need to pay the price or cost for those actions to return to the state of wellbeing and balance. The main purpose of utu is to maintain relationships. Where harm has taken place, utu may be needed to restore balance (ea) and thereby maintain whanaungatanga.[178]

271. The traditional practice of muru, to confiscate goods or personal property to redress a transgression, is closely related to utu. Muru was used as a collective form of social control or restorative justice within and between whānau, hapū and iwi.

Ea

272. Ea means the restoration of balance. This interrelationship can perhaps best be described using the framework presented by Sir Hirini Moko Mead KNZM: Take – Utu – Ea. Take means the reason or cause of something. In this context, the take is the action of tūkino that violates the mana and tapu of an individual or a collective. When the tūkino occurs, tikanga necessitates appropriate utu to be actioned to achieve the state of ea and the restoration of balance. The notion of ea indicates the successful closing of a sequence and the restoration of relationships.

I whai te Komihana i ngā tukanga mōtika tangata

The Inquiry took a human rights approach

273. The Inquiry’s Terms of Reference emphasised both Aotearoa New Zealand’s international legal obligations to protect individuals from abuse and neglect, and applicable standards and principles of human rights in Aotearoa New Zealand law on the proper treatment of people in care.[179]

274. In this section, the Inquiry discusses the core themes relevant to human rights that come from international declarations and obligations, international and domestic jurisprudence, United Nations committee decisions, commentary, and examples of guidelines developed to assist people to apply human rights themes in practice (such as the Scottish Human Rights Commission’s PANEL principles[180]). This section also discusses Aotearoa New Zealand’s human rights obligations.

Ngā kaupapa matua o te mōtika tangata

Human rights core themes

275. The core themes are:

- dignity

- universality

- self-determination

- equality and non-discrimination

- indivisibility

- measures of protection and assistance for certain groups to promote equality

- protection of the cultures, religions and languages of minorities

- participation in decision-making

- rule of law

- accountability and redress

- dynamism.

Amaru | Dignity

276. All human beings have intrinsic worth, inherent dignity and certain inalienable rights because they are human. Upholding the principle of human dignity has at least five aspects:

- banning all types of inhuman treatment, humiliation, or degradation of one person by another person

- protecting bodily and mental integrity

- ensuring the possibility of individual choice and the conditions for each person’s self-fulfilment, autonomy or self-realisation

- recognising that protecting peoples’ self-determination, identity and culture may be needed to protect personal dignity, and

- creating the conditions to ensure each person can have their essential needs met.[181]

277. This understanding of dignity is not based on an isolated individual. Rather, it promotes the freedom of people living together, related to and bound by community,[182] and dependent on each other for that freedom.

Tukupū | Universality

278. The fundamental nature of human rights means they apply universally to all people, and need to be universally respected, protected and fulfilled. The preambles to key United Nations declarations and covenants reflect this:

“Considering the obligation of States under the Charter of the United Nations to promote universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and freedoms…”[183]

Tino rangatiratanga | Self-determination

279. All peoples have the right of self-determination, including the right to freely determine their political status and pursue their economic, social and cultural development. In international law this right is commonly understood to apply to peoples, including indigenous peoples, rather than individuals. It may be subject to certain limits, including the territorial integrity and political unity of sovereign states.[184]

280. The right of self-determination is of fundamental importance, including for indigenous peoples.[185] The extent to which this right is realised affects the realisation of other rights by indigenous peoples and indigenous individuals. In Aotearoa New Zealand, Māori have the protection of te Tiriti o Waitangi rights and obligations as well as human rights and other international law.[186]

Mana ōrite me te kore whakatoihara | Equality and non-discrimination

281. Each human being has an equal right to have their human rights respected, protected and fulfilled. Discrimination, which violates this equality, is prohibited.

Wāhikore | Indivisibility

282. The fulfilment of civil and political rights, and economic, social and cultural rights, are equally needed to ensure human dignity.[187] Civil and political rights include, for example, the right not to be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Economic, social and cultural rights include, for example, the right to education, adequate food, clothing and housing, and the right to the highest achievable standard of physical and mental health. One set of rights cannot be enjoyed fully without the other. Some economic, social and cultural rights may be progressively realised over time rather than a State having to guarantee them immediately in full. Equal treatment is needed during this process.

Ngā whakaritenga tiaki, āwhina hoki mō ētahi rōpū hei whakarewa i te mana ōrite

Measures of protection and assistance for certain groups to promote equality

283. These groups include the family, mothers, children and disabled people. Measures that could be seen as discriminatory in other situations may be allowed for disadvantaged or vulnerable groups. In some cases, special measures may be needed to achieve equality for disadvantaged groups. This understanding informs, for example, the accessibility rights for disabled people affirmed in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and article 4 of the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which states that special measures to ensure equality between men and women should not be considered discrimination. The Scottish PANEL principles also prioritise people in the most marginalised or vulnerable situations who face the biggest barriers to realising their rights.[188]

284. These measures should not be conflated with the rights of indigenous peoples or people who belong to a minority group (such as the right to self-determination or the protection of the cultures of ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities). These groups are entitled to specific rights as well as measures to promote equality.[189]

Te tiaki i ngā ahurea, ngā whakapono me ngā reo o te tokoiti

Protection of the cultures, religions and languages of minorities

285. A person who belongs to an ethnic, religious or linguistic minority cannot be denied the right (together with other members of their group) to enjoy their own culture, practise their own religion or use their own language.[190] If that right has been violated, redress can include actions to promote, for example, the group’s culture and language. Actions to fulfil the right to take part in cultural life could be needed.[191]

Te whai wāhi ki ngā whakatau | Participation in decision-making

286. Individuals or groups whose rights may be affected by a certain decision have the right to be involved in making that decision.[192] How they must be involved has developed over time.[193] As part of ensuring that participation is effective and informed, and that rights are upheld, individuals and groups need to understand their rights.[194] A role of government is to promote this understanding. Indigenous peoples have the right to free, prior and informed consent in certain contexts, including the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and before legislative or administrative measures that may affect them are adopted.[195]

Te mana o te ture | Rule of law

287. All the actions of government, including law-making and the exercise of public power must be authorised by the law. Human rights must be protected by law and otherwise effectively protected.[196] Any limit on a right must be determined by law and consistent with the nature of that right.[197]

Te papanga me te puretumu | Accountability and comprehensive redress

288. There must be accountability for human rights breaches. To achieve accountability, the State must ensure effective monitoring, prompt investigations and remedies. Victims of human rights breaches must have effective redress from whoever is responsible for upholding the rights (duty holders).[198] Depending on the right breached, victims can be individuals or collectives,[199] and redress can be individual or collective.

Hihiritanga | Dynamism

289. Human rights have a dynamic aspect, meaning that the protection they provide increases over time as society’s understanding grows. Therefore, the obligations on Aotearoa New Zealand and other members of the international community in relation to human rights also increase over time.

Ngā takohanga mōtika tangata matua o Aotearoa

Aotearoa New Zealand’s key human rights obligations

290. Aotearoa New Zealand must respect, protect and fulfil human rights.[200] In practice, this means the State has a duty to:

- respect human rights by not interfering with them

- protect human rights by preventing private organisations or other people from violating them, and

- fulfil human rights by taking positive steps to ensure they are realised, including enacting laws and implementing appropriate policies and programmes.

291. Human rights should influence practice. People in care and people providing care should know about human rights and how they apply to care, and this knowledge must positively affect care relationships. Where it does not, that should be identified and remedied.

292. The Human Rights Act 1993 places obligations on public and private entities and individuals, in relation to sexual and racial harassment and other forms of unlawful discrimination.[201] Private organisations may have other human rights obligations under the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 if they are doing work on the State’s behalf, including when providing care for children, young people and adults in care.[202]

Te mana o ngā mōtika tangata, takohanga hoki o te ao i roto i ngā ture o Aotearoa

Status of international human rights and obligations in Aotearoa New Zealand law

293. Aotearoa New Zealand has had international human rights obligations since the beginning of the Inquiry’s scope in 1950. These human rights obligations have steadily increased over time and the United Nations has established international human rights standards for specific peoples and communities, for example, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

294. Aotearoa New Zealand has held itself up to the international community as supporting a range of international human rights standards, including those that existed before 1950.

295. Relevant international human rights declarations and conventions include:

- Universal Declaration on Human Rights 1948 (UDHR)

- International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination 1965 (CERD) (ratified by Aotearoa New Zealand in 1972)

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966 (ICCPR) (ratified by Aotearoa New Zealand in 1978)

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966 (ICESCR) (ratified by Aotearoa New Zealand in 1978)

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women 1979 (CEDAW) (ratified by Aotearoa New Zealand in 1985)

- Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment 1984 (CAT) (ratified by Aotearoa New Zealand in 1989)

- Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 (UNCROC) (ratified by Aotearoa New Zealand in 1993)

- Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty 1990 (adopted without vote by the General Assembly in 1990)

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2006 (UNCRPD) (ratified by Aotearoa New Zealand in 2008), and

- Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2007 (UNDRIP) (Aotearoa New Zealand voted against the declaration in 2007 but in 2010 changed its position to one of support).[203]

296. In Aotearoa New Zealand’s legal system, international rights and obligations cannot be directly relied on in the courts here unless they have been incorporated into a domestic statute, and some have not been. They can be relevant considerations in State decision-making, and the courts can take them into account in interpreting the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 and other domestic human rights statutes. There is a principle that statutes should be interpreted consistently with our international obligations where possible.[204]

297. Human rights protections in Aotearoa New Zealand’s domestic laws are “piecemeal”.[205] They are set out in a variety of statutes and the common (court-made) law. This means they cannot be found in one place.

298. The rights in the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act can broadly be defined as civil and political rights. Although the Act states that one of its purposes is to affirm Aotearoa New Zealand’s commitment to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, some rights recognised in the covenant are not in the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act.[206] Many of the rights affirmed in the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act were also protected by the common law.[207] This meant that before the enactment of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act, the rights affirmed in it could be upheld by using the common law. The same applies following the enactment. In many cases where a breach of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act can be shown, there will likely be a claim in part of the common law known as tort law.[208]

299. The Human Rights Act 1993 is primarily concerned with non-discrimination rights. The Act built on two previous statutes. One of these was the Race Relations Act 1971, enacted as part of Aotearoa New Zealand’s implementation of International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.[209] The other was the Human Rights Commission Act 1977, which established the Human Rights Commission.

300. Other domestic laws relevant to human rights include the Crimes Act 1961, the Ombudsmen Act 1975, the Official Information Act 1982, the Crimes of Torture Act 1989, the Privacy Act 1993, the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989/Children’s and Young People’s Well-being Act 1989, the Health and Disability Commissioner Act 1994 and the Accident Compensation Act 2001.[210]

I pēhea tā te Komihana whakaū i ēnei kaupapa mōtika tangata

How the Inquiry applied these human rights themes

301. The Inquiry used these human rights themes as a framework to guide its work. The Inquiry considers that these themes should have underpinned care in the past and must underpin it going forward.

302. The Inquiry considered abuse and neglect in care through this framework. This meant identifying where the State and faith-based institutions failed to uphold human rights and understanding how this affected survivors. Failures to uphold human rights could include, for example:

- a failure to protect children, young people and adults in care from inhumane or degrading treatment (the human rights theme of dignity), or

- a failure to provide protection and assistance to children in care (the human rights core theme of special measures of protection and assistance).

303. Part 5 describes the impacts of abuse and neglect in care, including how failures to uphold human rights have affected survivors. Part 7 sets out the Inquiry’s concluding observations about how the State and faith-based institutions failed to uphold their human rights obligations and commitments.

I tāpaetia he pou tarāwaho Turi, whaikaha, whaiora hoki e te Kōmihana

Deaf, disability and mental distress framework applied by the Inquiry

304. The Inquiry’s approach to understanding the experiences of Deaf survivors, disabled survivors, and survivors who experienced mental distress, was informed by the knowledge, expertise and work of its Deaf Reference Group, Disability Reference Group and Mental Health Reference Group and what it heard from survivors themselves, their whānau and communities.

305. The Inquiry acknowledges that Deaf people, disabled people and people who experience mental distress and their whānau and communities have their own histories, worldviews and values. The Inquiry acknowledges that Māori, Pacific Peoples and those who identify as Takatāpui, Rainbow or MVPFAFF+ who are also Deaf, disabled or experience mental distress have their own unique experiences and perspectives.

306. The Inquiry has used language that is considered best practice and is aligned with current thinking. We recognise, however, that other terms are used for disability and that language is a matter for self-determination. The Inquiry acknowledges that many Deaf people and people who experience mental distress do not self-identify as disabled. They are, however, included within the definition of disability in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).[211]

Ko wai te hunga Turi, te hunga whaikaha, me rātou e rongo ana i te wairangitanga?

Who are Deaf people, disabled people and people who experience mental distress?

307. Disabled people include people who have physical, sensory, communication or learning impairments, or are neurodivergent or a combination. The impairment can be present at birth or acquired during a person’s lifetime. Most Deaf people do not identify as disabled, but rather as a distinct community with their own language and culture.

308. Mental distress means a mental or emotional state that causes disruption to daily life and that can vary in length of time and intensity. People who experience mental distress includes those who are seriously upset, people who are reacting normally to a stressful situation, and people with mental illness (whether medically diagnosed or not).

309. Disability rights and issues are relevant to a significant number of people in Aotearoa New Zealand. In the latest reported New Zealand Disability Survey,1.1 million people were identified as disabled.[212] Many people have or live with disabled family members. Other key statistics include:

- Māori and Pacific Peoples are disproportionately represented as disabled – 26 percent of Māori (176,000 people) and 19 percent of Pacific Peoples (51,000 people) were identified as disabled[213]

- In children under 14 years old, 95,000 children were identified as disabled with a learning difficulty as their most common identified need[214]

- around 7,700 disabled people live in residential care homes funded by Whaikaha Ministry of Disabled People[215]

- there were about 4,600 Deaf people in Aotearoa New Zealand in the 2018 census[216]

- In 2022/23, 21 percent of young people aged 15–24 years and 11 percent of adults experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress[217]

- 11,299 people were subject to either compulsory assessment or compulsory treatment under mental health legislation.[218]

310. Despite the large number of affected people and the impact of barriers experienced in so many people’s lives, disability issues remain relatively invisible in political and public discourse in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Ngā mōtika me te tuakiri o te hunga Turi, te hunga whaikaha, me te hunga wairangi

Deaf, disability and mental distress rights and identities

311. The identity of Deaf people, disabled people and people who experience mental distress depends on each person’s perspective. It can vary widely, and can change over time. Understanding of disability concepts and identities is diverse and continues to evolve.

312. Disabled people understand disability as a rights-based issue. Discrimination against disabled people was not illegal in Aotearoa New Zealand until the introduction of the Human Rights Act in 1993.[219] The international disability rights movement led to the 2006 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Disabled people’s specific rights are described in the Convention, but not all these rights have been incorporated into Aotearoa New Zealand’s domestic law.

313. People with multiple impairments continue to face barriers that non-disabled people take for granted, such as autonomy, participation, full citizenship and recognition as productive members of society.[220] The disability community continues to work towards addressing the gap between disabled people’s rights and the realities of their daily experiences.

314. Since colonisation in Aotearoa New Zealand, disability has been understood in medical terms with a deficit perspective. The development of the social model of disability, led by disabled people through the disability rights movement, offered an alternative perspective – that “it is society that disables us, not our impairments”.[221] The social model states that barriers to daily life that limit a disabled person’s participation are created by social oppression and exclusion, not by the person’s abilities. While the social model was instrumental in shifting perspectives on disability, it has since been critiqued. Among the critiques is that the social model is simplistic,[222] and does not fully incorporate indigenous worldviews.[223]

315. Indigenous perspectives on impairment encompass spiritual, holistic, relational and environmental dimensions.[224] Medical concepts of impairment and its associated social attitudes had no equivalent in traditional Māori society.[225] Narratives passed down through pūrākau, waiata and whakataukī refer to atua and tīpuna whose differences were celebrated or seen as a source of greatness or special power.[226] For example, Tāwhirimātea, god of the weather, and Turikatuku (Ngāpuhi), wife of Hongi Hika and credited as his war strategist, were kāpō (blind).[227] Tāngata whaikaha Māori are working to develop concepts of disability that reflect te ao Māori and are grounded in te Tiriti o Waitangi.[228]

316. Ableism and disablism contribute to the barriers experienced by disabled people by creating discrimination. Ableism is the value system that results in attitudes and behaviours through which society privileges certain characteristics over others. For example, privileging the non-disabled body over the disabled body. Ableism is widespread and systemic, and often arises from ignorance rather than conscious intentional discrimination and harm. Invisibility of disabled people and disability issues in the public discourse contributes to ableism because disabled people and disability issues are invisible to decision-makers. They then make decisions without being aware of how the decisions will affect disabled people.

317. Disablism is conscious, direct discrimination against people who are disabled, based on their disability.[229]

Mātāpono

Principles

318. The principles set out below are taken from the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Enabling Good Lives. Based on what survivors, their whānau and communities shared about their experiences, the Inquiry found these principles appropriate to help frame its understanding and analysis of the abuse and neglect suffered by Deaf survivors, disabled survivors and survivors who experienced mental distress.

Ngā mātāpono o te Kawenata mō ngā Mōtika o te Hunga Whaikaha

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities principles

319. There are eight guiding principles of the Convention. The principles provide the inherent dignity of an individual and their autonomy. The principles are:

- Respect for inherent dignity

- Non-discrimination

- Full and effective participation and inclusion in society

- Respect for difference

- Equality of opportunity

- Accessibility

- Equality between genders

- Respect for evolving capacities.

Te whakaute i te mana tuku iho | Respect for inherent dignity

320. Every person has their own mana, value and associated rights, no matter who they are. All people and communities have equal worth regardless of any characteristic, including impairment. All people are entitled to the same dignity and acknowledgement in society. Deaf people, disabled people and people who experience mental distress have the right to respect for their bodily and mental integrity.

321. Deaf people, disabled people and people who experience mental distress can determine their own outcomes and be in control of their own lives, including designing and managing their support systems. They have the dignity of risk, which means choosing to take risks if they want to.[230] That control includes choosing whether to involve whānau and other collectives (such as friends and advocates) in their decisions through supported decision-making.

Te kore whakatoihara | Non-discrimination

322. Non-discrimination includes the right to be free from segregation from the community, forced placement in institutions, separation of children from whānau, and forced treatment.[231]

Te whai wāhi me te noho tahi ki te pāpori | Full and effective participation and inclusion in society

323. Deaf people, disabled people and people who experience mental distress, and their families have the resources to be involved at all levels of work and development of arrangements relevant to them and their families’ lives. This principle builds on the internationally recognised concept of participation – “Nothing about us without us”[232] – which emphasises that no policy, decision, action or practice should be undertaken without the full, effective participation, consent and leadership of those who would be most affected. For Māori, this right of participation includes their rights as partners to te Tiriti o Waitangi and their right to free, prior and informed consent as indigenous peoples under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples.

324. Every person has the right to be part of a family, included in the community, attend their local school, and to work or shape their lives as they wish. This principle rejects the models that segregate and congregate people socially and physically. Deaf people, disabled people and people who experience mental distress have the right to fully participate in socially expected roles and activities and contribute as equal citizens in society as they choose.

325. Inclusion requires a whole-of-life approach, where people, families, and communities have the resources needed to flourish, a sense of purpose, and are hopeful about the future. Disabled people have the right to access all cultures and communities they choose to identify with, including Deaf culture.

Te whakaute i ngā rerekētanga me te aroha ki te hunga whaikaha e eke ai te kanorautanga me te koutangata |

Respect for difference and acceptance of persons with disabilities as part of human diversity and humanity

326. All people must be equally respected and recognised. Deaf people, disabled people and people who experience mental distress have equal value and worth, and difference is to be celebrated.

327. This principle recognises and celebrates the diversity of Deaf people, disabled people and people who experience mental distress, who all have different experiences and circumstances and the right to be valued and treated equally. The diversity of cultural aspects of their identities must also be respected. For example, Deaf people have their own culture and language (New Zealand Sign Language) that is part of their identity.

328. It also recognises the impact of the compounding marginalisation of stigma, ableism, disablism, audism (discrimination against Deaf people and people with hearing loss), oralism (the belief that Deaf people and people with hearing loss should communicate by lip reading and speaking, rather than sign language), racism, homophobia, transphobia and other forms of discrimination.

329. This principle builds on the phrase “Know me before you judge me”, which calls to end stigma, ableism and disablism. People should be asked, “What are your strengths and what do you need to live a good life?” rather than “What is wrong with you that we need to fix?” For some people this means living well in the presence of the ‘symptoms’ of their impairments.

Ngā ara tautika | Equality of opportunity

330. Deaf people, disabled people and people who experience mental distress must have the same opportunities as everyone else to live their lives, to work, to realise their potential and to participate as active members of society.

Ngā āheitanga | Accessibility

331. Deaf people, disabled people and people who experience mental distress must have equal access to the physical environment, transportation, information and communication, technologies, public facilities and services, so they can live independently and participate fully in all aspects of life.[233]

Te manarite ā-ia | Equality between genders

332. This principle recognises that disabled women and girls face multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination and barriers to enjoying and exercising their rights.

Te whai whakaaro ki ngā āheitanga hurihuri | Respect for evolving capacities

333. Respect for the evolving capacities of Deaf children, disabled children and children who experience mental distress, and respect for their right to preserve their identities.

Ngā mātāpono o te Mana Whaikaha | Enabling Good Lives principles

334. The Enabling Good Lives principles were developed to guide the transformation of the disability support system. Through Enabling Good Lives, Deaf people, disabled people and their whānau can choose to increase the choice and control they have in their lives and supports. The Government agreed to nationwide implementation of the Enabling Good Lives approach in October 2021.[234] At the time of this report, supports and treatment for people who experience mental distress are primarily provided through the health system, not through the disability support system.

335. The Enabling Good Lives principles recognise the rights of Deaf people, disabled people and their whānau to receive the support needed to live a good life as they define it. This includes support to leave institutionalised settings. These principles recognise the interdependence and interconnectedness of people, whānau and communities and that, for some people (including Māori and Pacific Peoples) decisions should be made collectively and with the support and participation of whānau. They promote self-determination, including by providing for disabled people and their whānau to use allocated funding flexibly to meet their needs. They affirm that collective advocacy, based on best interpretation of a person’s will and preferences, is needed for some who may not be otherwise able to independently articulate their needs.

336. The Enabling Good Lives principles are:

- Self-determination – Deaf and disabled people are in control of their lives.

- Beginning early – invest early in families and whānau to support them to be aspirational for their children, to build community and natural supports and to support children to become independent, rather than waiting for a crisis before support is available.

- Person-centred – Deaf and disabled people have supports that are tailored to their individual needs and goals, and that take a whole-of-life approach rather than being split across programmes.

- Ordinary life outcomes – Deaf and disabled people are supported to live an everyday life in everyday places and are regarded as citizens with opportunities for learning, employment, having a home and family, and social participation like others at similar stages of life.

- Mainstream first – Deaf and disabled people are supported to access mainstream services before specialist disability services.

- Mana enhancing – the abilities and contributions of Deaf people and disabled people and their families are recognised and respected.

- Easy to use – Deaf and disabled people have supports that are simple to use and flexible.

- Relationship building – supports build and strengthen relationships between Deaf and disabled people, their whānau and community.[235]

I tāpaetia he pou tarāwaho uara Pasifika e te Kōmihana

Pacific values framework applied by the Inquiry

337. The Inquiry’s Terms of Reference directed it to recognise the status of Pacific Peoples in Aotearoa New Zealand, and that Pacific Peoples have been disproportionately represented in State and faith-based care.[236]

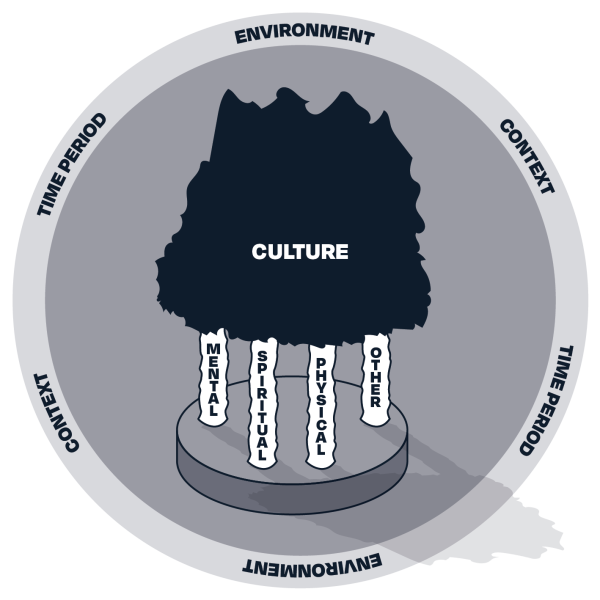

338. He Purapura Ora, he Māra Tipu discussed the Fonofale model of Pacific health and wellbeing, which Pacific experts spoke to the Inquiry about.[237] The Fonofale model uses the metaphor of a Samoan fale (house) and includes elements from many Pacific nations including the Cook Islands, Niue, Fiji, Tokelau and Tonga. The foundation of the fale represents family, which is generally seen as the foundation for all Pacific cultures. Four pou between the roof and the foundation – spiritual, physical, mental and other – each represent a fundamental element of a person’s wellbeing. The fale sits inside a cocoon that contains three other elements that influence a person’s wellbeing – the environment, time, and context.[238]

339. Informed by the knowledge, expertise and work of the Pacific Reference Group and the Fonofale model of Pacific wellbeing, the Inquiry used a values framework that was inclusive of all Pacific Peoples to guide its work. These values reflected what the Inquiry heard from Pacific survivors, their families, and others from Pacific communities. In preparing this report and applying the Pacific values framework, the Inquiry was conscious of approaching Pacific Peoples’ diverse experiences with humility, or vakarokoroko in vosa vakaviti (Fijian language), and respect.[239]

340. The Inquiry acknowledges that each individual Pacific culture is unique in its history, worldview and values, and in how its values are upheld, including how rituals and ceremonies are performed. However, common values and concepts relating to the space of conflict or dispute resolution can be identified across many Pacific cultures. Though these cultures are not homogenous, it is generally accepted that there are enough shared values to be able to speak of Pacific values, beliefs and guiding principles.

Uara Pasifika | Pacific values

341. The English translations of these concepts do not fully capture the depth or contexts of their meanings, or the unique ways in which they are lived out in the day-to-day practices of Pacific communities. In prioritising Pacific languages, the Inquiry selected examples from different Pacific languages to represent each value. The chosen words and concepts best reflect the work of this Inquiry and the voices of survivors, while acknowledging the differences across Pacific languages and cultures.

342. The Pacific values used by the Inquiry (building on values first set out in Tāwharautia: Pūrongo o te Wā) are:

- kainga, which means family in te taetae ni Kiribati (Kiribati language)

- fa’aaloalo, which means respect in agana Samoa (Samoan language)

- fetokoni’aki, which means reciprocity in lea faka-Tonga (Tongan language)

- aro’a, which means love in reo Māori Kūki ‘Āirani (Cook Islands Māori language)

- tapuakiga/talitonuga, which means spirituality, indigenous beliefs and Christianity, in agana Tokelau (Tokelaun language)

- kaitasi, which means collectivism and shared responsibility in gana Tuvalu (Tuvaluan language).[240]

Kāinga

343. Kāinga means family in te taetae ni Kiribati (Kiribati language). Kāinga includes the local extended family unit and their place of residence.[241] It also means home and “the land that feeds”.[242] Kāinga usually consisted of a family descended from a common ancestor[243] but adoption was also noted as a key feature of family and social organisation.[244] Including both people and place, kāinga is central to community, identity, and belonging.

Fa’aaloalo

344. Fa’aaloalo means respect in agana Samoa (Samoan language). For Samoans, it is not only a way to live but a way to behave.[245] These ways of living encompass everything from entering homes, greeting one another and speaking to elders, to managing and navigating social hierarchies. “Everything is done with fa’aaloalo”[246] and fa’aaloalo “should be for all”.[247] This includes people in marginalised groups (for example, women, disabled people and MVPFAFF+ people) who may be expected to show respect even while they are not always held in respect.[248] Understanding fa’aaloalo is useful in identifying when and where respect is absent and how this absence can lead to abuse and neglect.

Fetokoni’aki

345. Fetokoni’aki means reciprocity in lea faka-Tonga (Tongan language). It means reciprocal co-operation or mutual helpfulness. It also describes “unity and co-operation between family members”.[249] It “points to the idea that wellbeing within a Tongan worldview is achieved through processes of reciprocity and mutuality”.[250] Fetokoni’aki is a part of everyday life.[251]

Aro’a

346. Aro’a means love in reo Māori Kuki ‘Āirani (Cook Islands Māori language). It includes love, respect, hospitality, kindness, concern for others and forgiveness.[252] Aro’a is one of the most important acts in the Cook Islands Māori world, because “it is the highest regard we can have for our communities, our ancestors and each other”.[253] Aro’a is closely tied to the health and wellbeing of individuals, families (including multiple generations), and the wider community.

Tapuakiga / talitonuga

347. Tapuakiga/talitonuga means spirituality in gagana Tokelau (Tokelauan language). It includes spirituality, indigenous beliefs and Christianity, and is an integral part of Pacific life.[254] Though the introduction of Christianity may have suppressed some indigenous beliefs, it did not obliterate them.[255] These Tokelauan concepts acknowledge both indigenous beliefs and Christianity and recognise the ways they overlap, and the ways Pacific Peoples have worked with them and challenged them over time.[256]

Kaitasi

348. Kaitasi means collectivism and shared responsibility in gana Tuvalu (Tuvaluan language). It means to eat together and is also the name for the communal land tenure system in Tuvalu.[257] Kaitasi can be invoked to address the need for communalism, or the sharing of responsibility, because what happens in one part affects others.[258] It includes the idea that sharing responsibility – whether for food and nourishment, for care, or for support for family and community – is integral to the future of the people.

Vā – te ‘āputa’ tūhonohono

349. Pacific worldviews have a strong emphasis on relationships and the intrinsic interconnections, or vā, between people and the material and spiritual worlds. According to Dr Sam Manuela, a “holistic conceptualisation of the self”, from a Pacific perspective, is formed “in relation to others”. This, very importantly, includes those one is related to.[259]

350. The values described above are interwoven and intersecting, often overlapping with one another. These values are understood to exist, come together, have meaning and interact within the concept of vā, which is the “space between” that holds people and things together.[260] When these values are honoured and practised, they create and reflect the conditions for honouring the vā. In vagahau Niue (Niuean language), fakatupuolamoui means the interrelatedness of wellbeing or how “through the proper conduct of one, the spirit of the other is encouraged to grow and flourish”.[261] As discussed in a Niuean conceptual framework for addressing violence, fakatupuolamoui means “to thrive vigorously and abundantly”.[262]

Ētahi atu huatau e hāngai ana ki te tūkinotanga me te whakahapatanga

Other concepts relating to abuse and neglect