Chapter 5: The extent of abuse and neglect in care Ūpoko 5: Te roanga o te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa i roto i te pūnaha taurima

1035. This chapter discusses the extent of abuse and/or neglect in care over the Inquiry period, including what is known about where abuse and/or neglect occurred and the people who were abused and/or neglected. It draws on a wide range of information, including evidence from survivors and witnesses, information requested from organisations, evidence from public hearings for State and faith-based institutions, and published research and reports.

1036. Estimates of the extent or prevalence of abuse and/or neglect are presented for the overall group of people who went through care, as well as for the different types of setting experienced by survivors.

1037. This Inquiry is unable to conclusively state the number of those who went through care, or who were abused and/or neglected while in care. Instead, this chapter presents estimates of how many people probably experienced abuse and/or neglect while in care. These estimates include international studies of the prevalence of abuse and/or neglect in similar care settings overseas. While there are many limitations to the Inquiry’s available information, the extent of abuse and/or neglect was clearly significant in many different forms and in most, if not all, of the settings that were investigated.

1038. These estimates should be read with full consideration of the hundreds of survivors whose experiences of abuse and neglect in State and faith-based care has been detailed in this report.

1039. It is also important to note that the definitions outlined in Chapter 2 are not fully captured in the estimates used in this chapter. This chapter largely relies on research by MartinJenkins and DOT Loves Data. MartinJenkins used different definitions of abuse and neglect whereas DOT Loves Data’s research was mostly based on the Inquiry’s definitions but could not fully capture all aspects and nuances of each form.

He whakatau tata i te tātai te hunga i tūkinotia i o te pūnaha taurima i Aotearoa

Estimating the number of people abused in care in Aotearoa New Zealand

1040. Estimates were provided to the Inquiry in the 2020 MartinJenkins report, commissioned to help assess the numbers of people in care, and numbers who were abused in care, within the scope of the Inquiry’s Terms of Reference.[1431]

1041. The MartinJenkins report estimated that about 655,000 people passed through State and faith-based care settings from 1950 to 2019 – with an estimated 254,000 people in faith-based settings, 258,000 people in social welfare settings, 212,000 people in Health and Disability settings and 102,000 people in education care settings.[1432] Using this figure as the ‘care cohort’, that report provided low and high estimates of 114,000 and 256,000 respectively for how many of those people may have been abused and/or neglected. This amounts to a prevalence rate for abuse and neglect across all State and faith-based care settings of 17 percent using MartinJenkins’ low estimate, while their high estimate would be 39 percent of that group.[1433]

1042. In addition to MartinJenkins’ quantitative analysis, the qualitative accounts that survivors and staff have provided the Inquiry show that both abuse and neglect were prevalent throughout many care settings during the Inquiry period. In reaching this conclusion, the Inquiry has also considered evidence from experts, representatives of State and faith-based institutions, and existing research.

Ngā momo tūkinotanga me ngā whakahapatanga i roto i te pūnaha taurima i ripoatahia ki te Kōmihana

Types of abuse and neglect in care reported to the Inquiry

1043. From 2018 to 2023, the Inquiry received accounts of abuse from more than 2000 survivors. These accounts are both compelling and credible, with statements about the extent of abuse experienced or witnessed by individual survivors consistently supported through information provided by others.

1044. DOT Loves Data (DOT) was engaged by the Inquiry to produce quantitative analysis of these survivor accounts. The 2,329 survivors who gave evidence to the Inquiry are a self-selecting subset of the overall care cohort, and do not represent all those who were in care from 1950 to 31 July 2023 (the date of when the Inquiry stopped receiving evidence from Survivors).

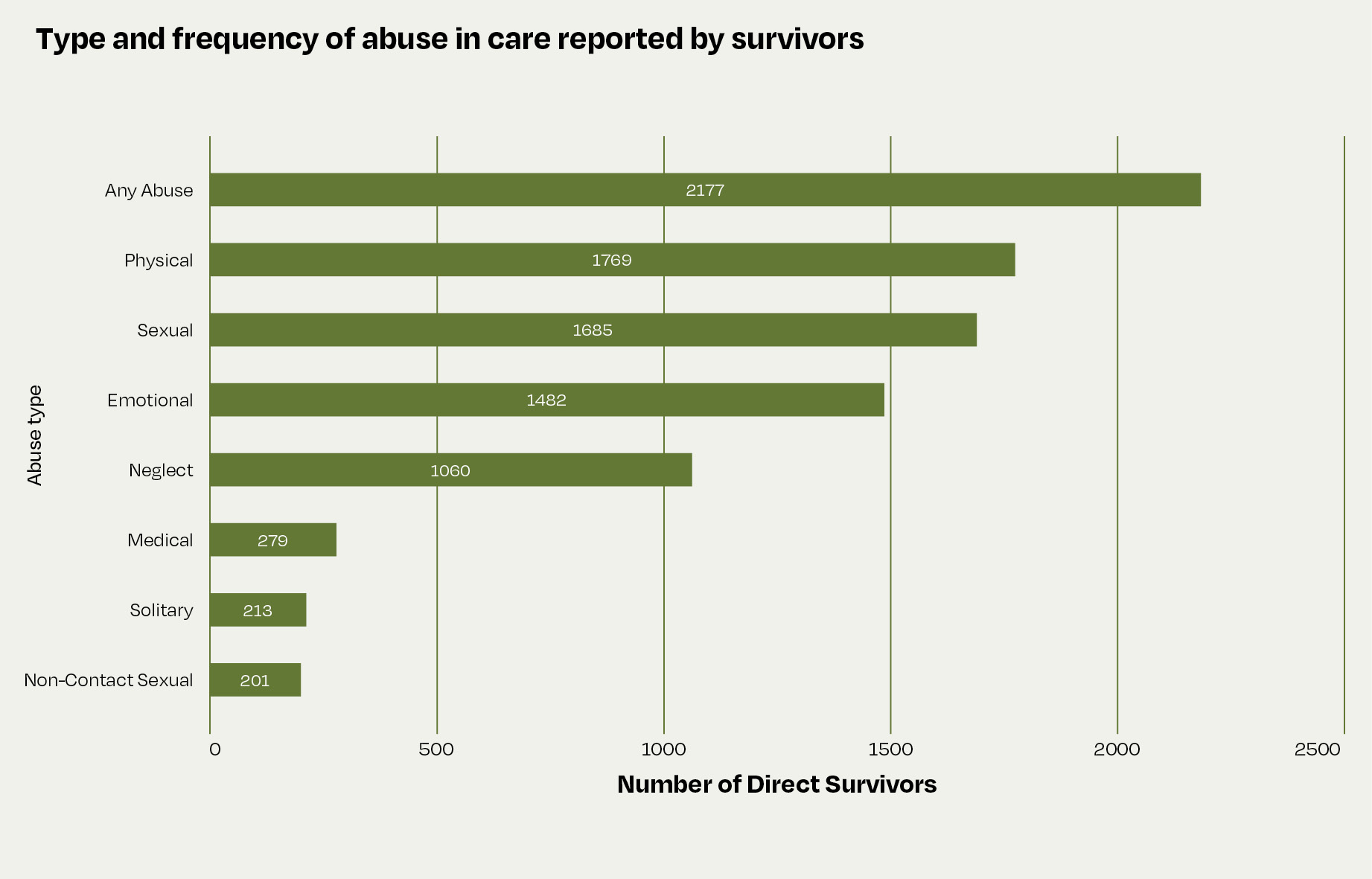

1045. This Inquiry investigated all different types of abuse and neglect that could have applied to survivors in State and faith-based care (including direct and indirect) institutions. DOT Loves Data’s analysis of the data focused on and coded seven key types of abuse: physical, sexual, non-contact sexual, emotional, neglect, medical, and solitary.[1434] The analysis indicated that physical abuse was the most common type of abuse reported by survivors, followed by sexual and emotional abuse, as seen below:

Type and frequency of abuse in care reported by survivors

1046. The total amount of incidents across all categories of abuse is far higher than the number of survivor accounts received, which indicates that most survivors who spoke to the Inquiry experienced multiple types of abuse or neglect while they were in care.

1046. The total amount of incidents across all categories of abuse is far higher than the number of survivor accounts received, which indicates that most survivors who spoke to the Inquiry experienced multiple types of abuse or neglect while they were in care.

1047. It was acknowledged during the Inquiry’s public hearings that, in addition to Māori, Pacific, and disabled people being disproportionately represented in care, they also probably suffered increased abuse.[1435]

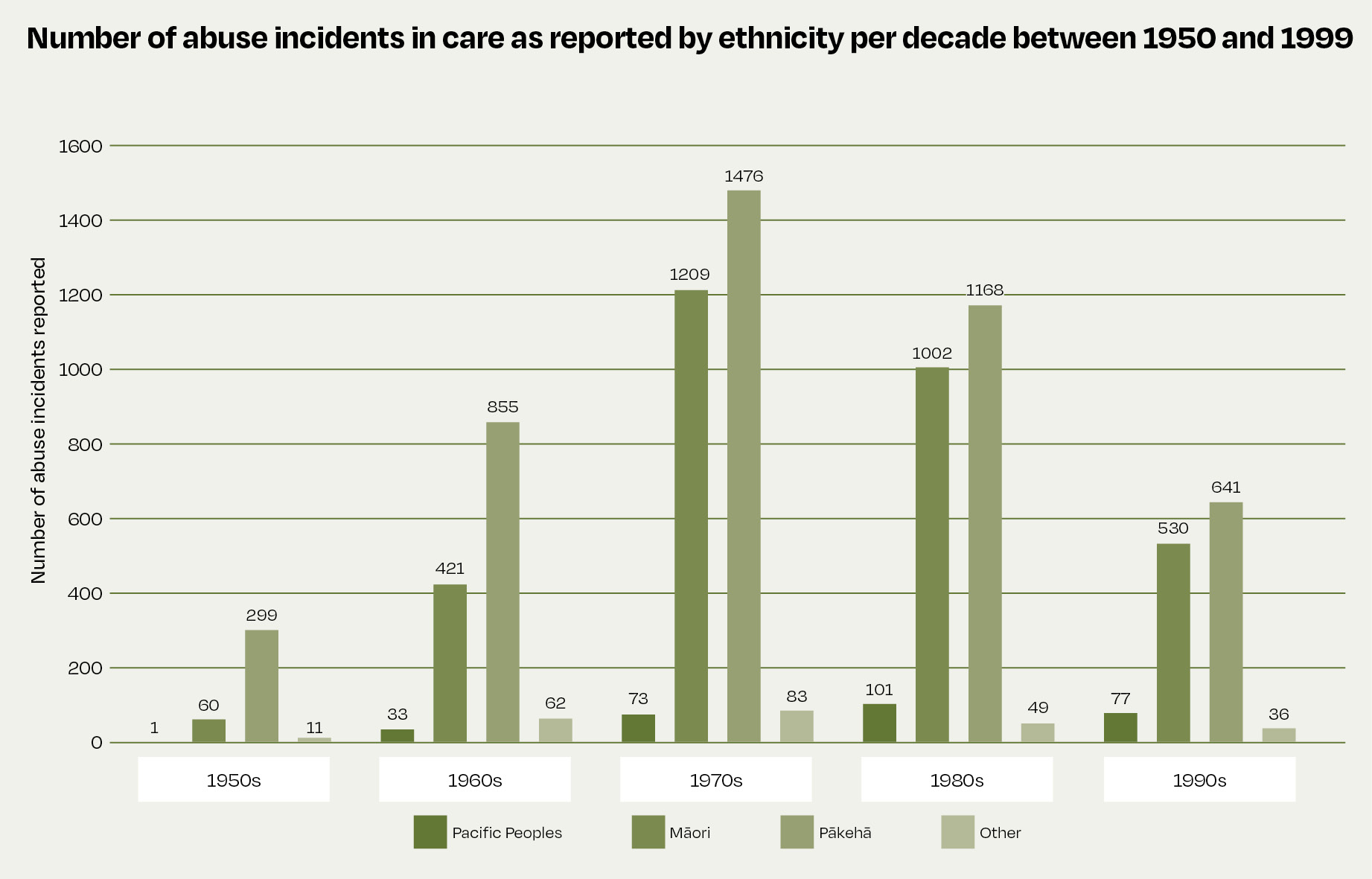

1048. The decade with the highest rates of abuse and neglect was in the 1970s, followed by the 1980s, and then the 1960s. The decade of the 1970s has also emerged as a time of increased abuse incidents.[1436]

1049. The graph below shows DOT’s analysis of the number of abuse incidents reported by each decade of the scope period. [1437] The data is grouped by ethnicity and includes Pacific Peoples, Māori, Pākehā and other, which includes Middle Eastern, Latin American, African, Asian, other ethnicity, survivors who preferred not to say, and where the data is not known:

Number of abuse incidents in care as reported by ethnicity per decade between 1950 and 1999 1050. Children aged 10 to 14 years old endured high levels of sexual and physical abuse.[1438] Māori and Pacific survivors endured higher levels of physical abuse than other ethnicities,[1439] and disabled survivors reported higher levels across all abuse types.[1440] This suggests that the age, ethnicity, and disability status of survivors played a role in the abuse and neglect they were subjected to.

1050. Children aged 10 to 14 years old endured high levels of sexual and physical abuse.[1438] Māori and Pacific survivors endured higher levels of physical abuse than other ethnicities,[1439] and disabled survivors reported higher levels across all abuse types.[1440] This suggests that the age, ethnicity, and disability status of survivors played a role in the abuse and neglect they were subjected to.

Ngā rerekētanga ā-ira o ngā wheako o te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

Gendered differences in experiences of abuse and neglect

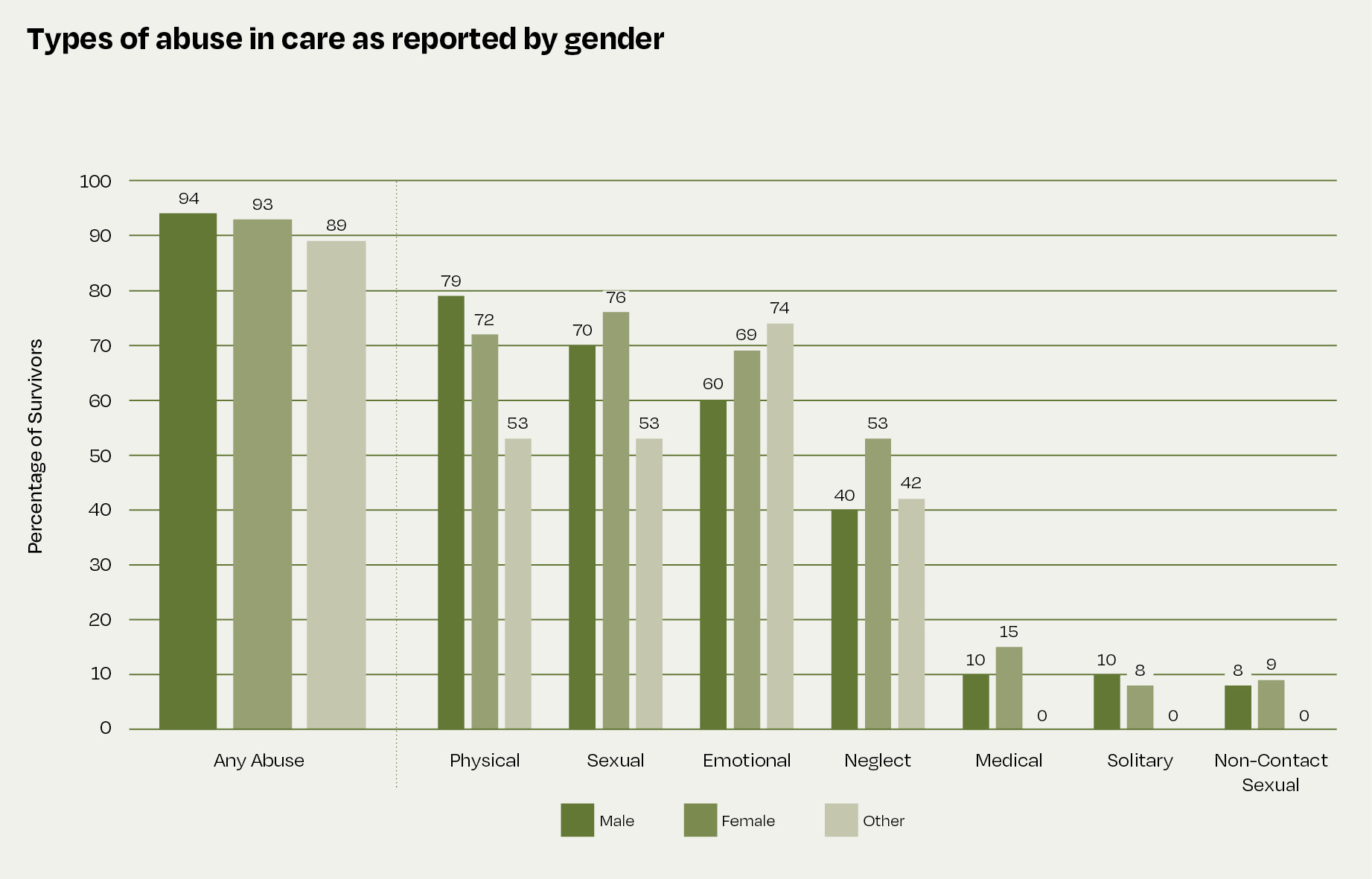

1051. While survivors of all genders experienced all different types of abuse across all of the different settings the Inquiry investigated, there were differences in what proportion of accounts featured different types of abuse occurring in different settings. The graph below shows analysis by DOT Loves Data of the types of abuse reported by different genders in care. The genders are male, female and other, which includes gender diverse, non-binary or preferred not to say or there was no data.[1441]

Types of abuse in care as reported by gender

Ngā momo tūkinotanga ka wheakotia e ngā purapura ora wāhine

Types of abuse experienced by female survivors

1052. Analysis of evidence from the female survivors the Inquiry heard from shows that emotional and sexual abuse were the types of abuse they most frequently experienced, occurring at least once in 58 percent and 57 percent of these accounts respectively.[1442] In addition, 52 percent of female survivors were physically abused while in care and 34 percent experienced neglect.

1053. Looking at different types of care settings, more than half of female survivors who went through social welfare care settings experienced sexual abuse (55 percent), with similar proportions for emotional and physical abuse (51 percent of reports for each).[1443] Thirty-four percent of female survivors also reported experiencing neglect while in social welfare care settings.

1054. In faith-based care, emotional abuse and sexual abuse were the abuse types most experienced by female survivors, at 48 percent and 46 percent respectively. For female survivors in disability and mental health settings, emotional and physical abuse were the most common types, at 42 percent and 41 percent of the cohort respectively.

Ngā momo tūkinotanga ka wheakotia e ngā purapura ora tāne

Types of abuse experienced by male survivors

1055. The evidence provided to the Inquiry by male survivors shows that the most frequently experienced type of abuse across all settings was physical abuse. 60 percent of survivor accounts demonstrated this point.[1444] The next most common types of abuse were sexual abuse (57 percent), and emotional abuse (48 percent).

1056. Within social welfare care settings, physical abuse remained the most common type of abuse and was included in 60 percent of accounts from male survivors.[1445] Sexual abuse in social welfare care settings was experienced in almost half of these accounts (49 percent), while emotional abuse appeared in 44 percent. In addition, a quarter of male survivors of social welfare care settings described being neglected while they were there (25 percent).

1057. In terms of faith-based settings, again almost half of male survivors were sexually abused while they were there (49 percent).[1446] The next most frequent abuse types were physical and emotional, at 38 percent and 34 percent respectively. Looking at dedicated disability and mental health care settings, male survivors were physically abused in 45 percent of their accounts.

Ngā momo tūkinotanga ka wheakotia e ngā purapura ora ia-kore, kāore i herea ki te ia-tāne, te ia-wahine rānei

Types of abuse and neglect experienced by survivors who are non-binary or do not identify as male or female

1058. For survivors who are gender diverse, non-binary or gave an ‘other’ response when identifying their gender, the abuse type most frequently experienced was emotional abuse, which was included in 62 percent of their accounts. In addition, high proportions of their accounts featured physical abuse (44 percent), sexual abuse (44 percent), and neglect (44 percent).[1447]

Ngā momo tūkinotanga i rāngona e ngā purapura ora whaikaha

Types of abuse experienced by disabled survivors

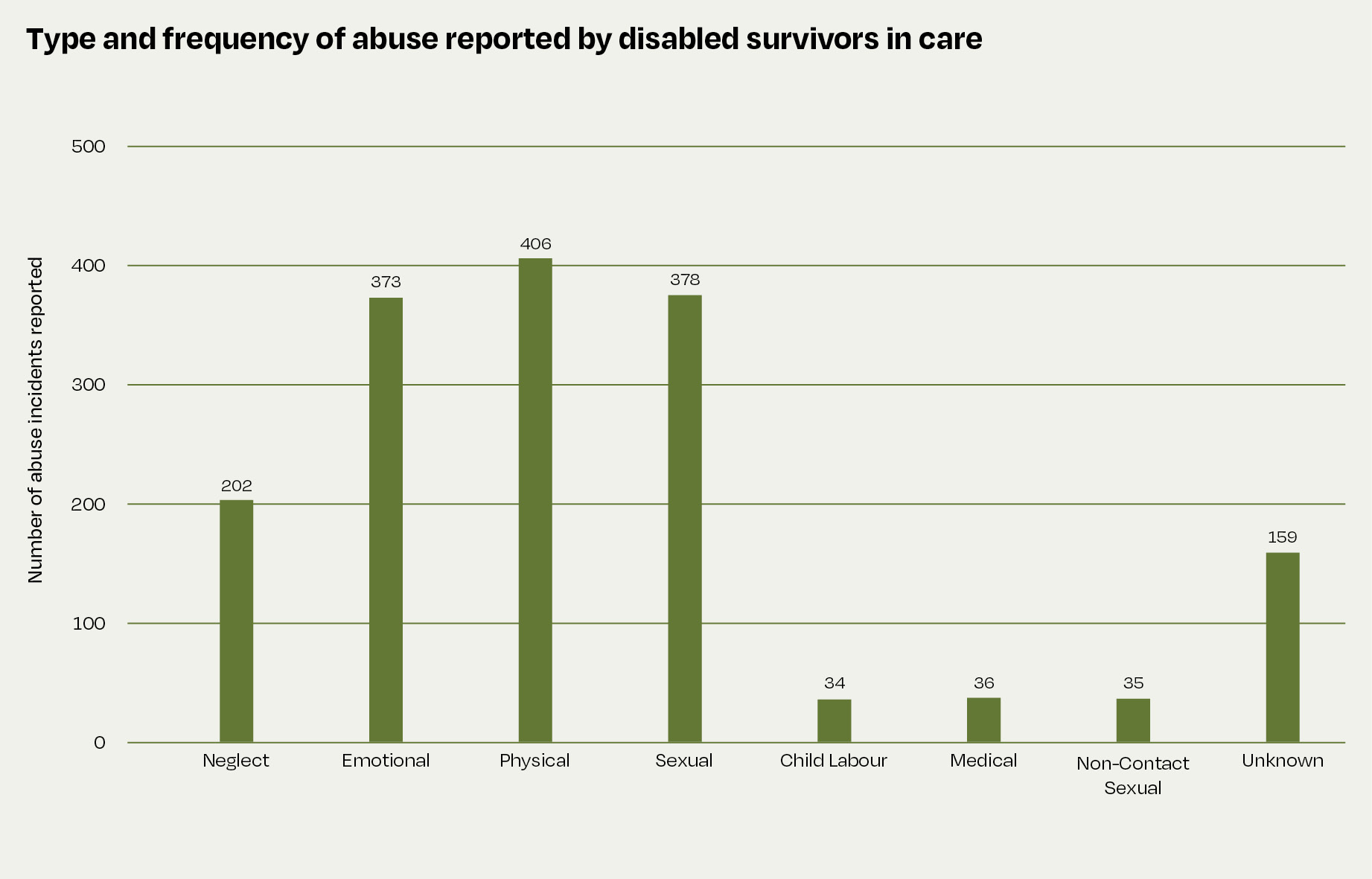

1059. Many survivors who have or had a disability gave evidence to the Inquiry about experiencing all types of abuse across all the settings they were placed in. Survivors with different disabilities and impairments are discussed as part of the setting-specific analysis later in this chapter. Analysis by DOT Loves Data of the number of disabled survivors who reported each abuse type across all settings is shown below. The most common types of abuse reported by disabled people were physical, sexual and emotional, followed by neglect:[1448]

Type and frequency of abuse reported by disabled survivors in care

Ngā momo tūkinotanga ka wheakotia e ngā purapura ora kua mauherea

Ngā momo tūkinotanga ka wheakotia e ngā purapura ora kua mauherea

Types of abuse experienced by survivors who have been in prison

1060. The Inquiry also examined the accounts of survivors who have been in prison at some point after leaving care. The most reported abuse type was physical, which was included in 69 percent of accounts. The next most common types were sexual abuse (63 percent), and emotional abuse (55 percent). In addition, 30 percent of survivors who were in prison were also neglected while they had been in care.

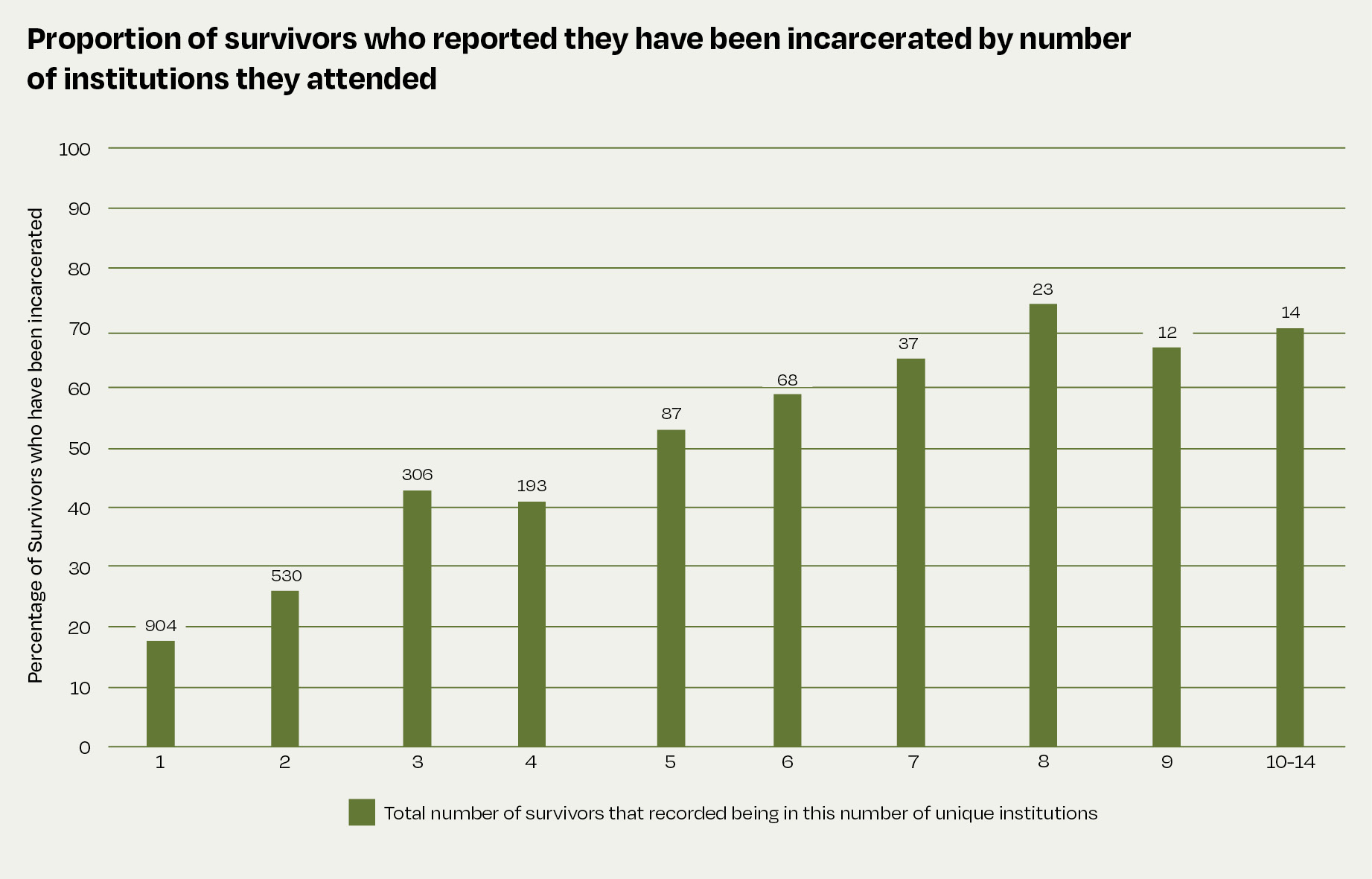

1061. Further analysis by DOT Loves Data indicated that survivors were more likely to go to prison if they attended five or more institutional settings, compared with those survivors placed in four or fewer of these settings. The graph below shows the proportion of survivors who reported they have been incarcerated increases as the number of unique institutions they attended increases:[1449]

Proportion of survivors who reported they have been incarcerated by number of institutions they attended

Ngā momo tūkinotanga i te roanga ake o te wā mātai o te Pakirehua

Ngā momo tūkinotanga i te roanga ake o te wā mātai o te Pakirehua

Different types of abuse throughout the Inquiry’s scope period

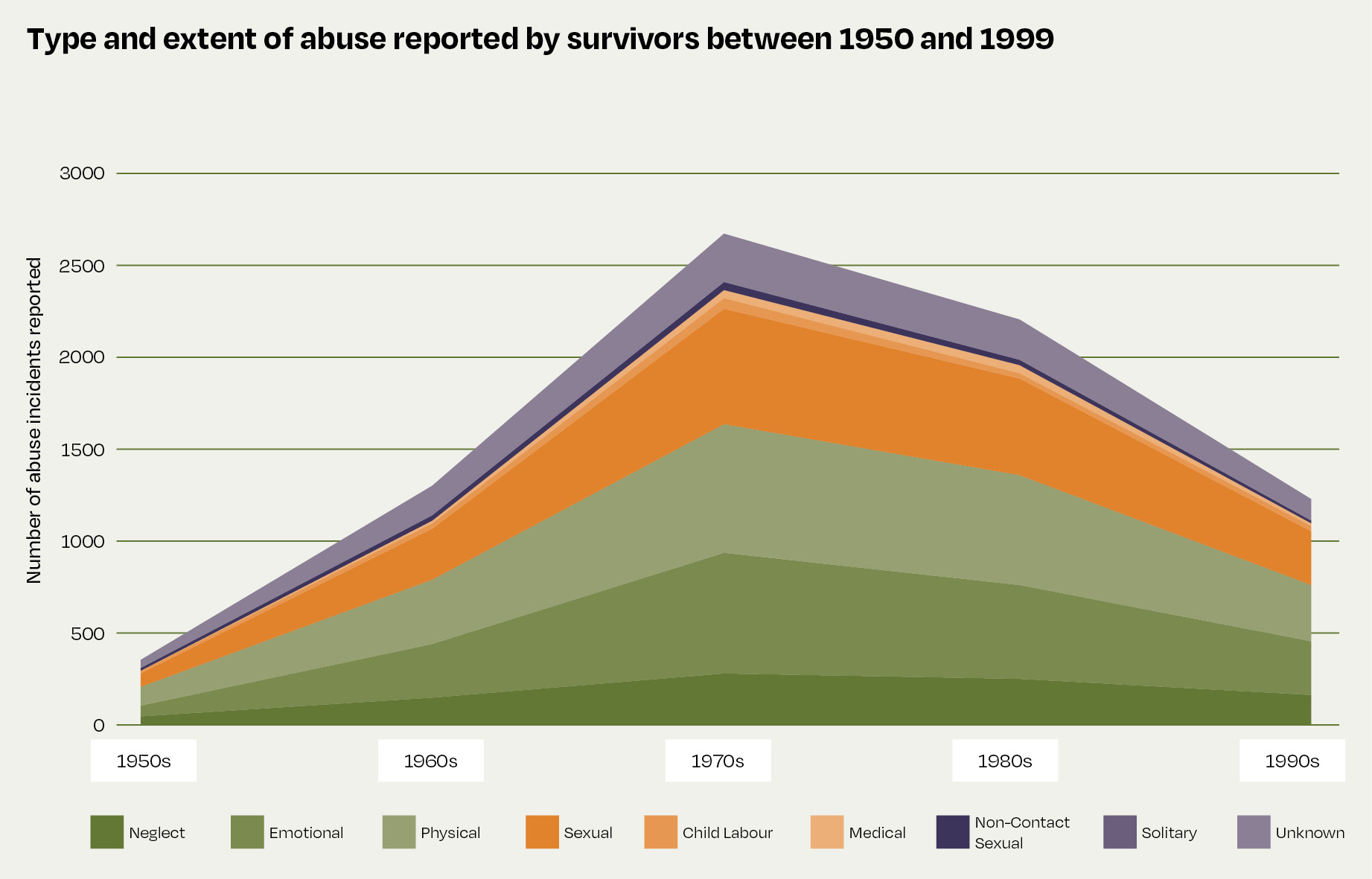

1062. Although the extent of different types of abuse experienced by survivors differed throughout the scope period and between different groups, there are evident trends where sexual, physical and emotional abuse were consistently the most commonly reported types of abuse. It is also evident that the volume of reported abuse peaked in the 1970s. The graph below shows DOT Loves Data’s analysis of the type and extent of abuse reported by survivors between 1950 and 1999[1450]

Type and extent of abuse reported by survivors between 1950 and 1999

1063. Many survivors experienced multiple abuse and neglect types. For example, 82 percent of survivors who experienced sexual abuse also reported physical abuse.[1451]

1063. Many survivors experienced multiple abuse and neglect types. For example, 82 percent of survivors who experienced sexual abuse also reported physical abuse.[1451]

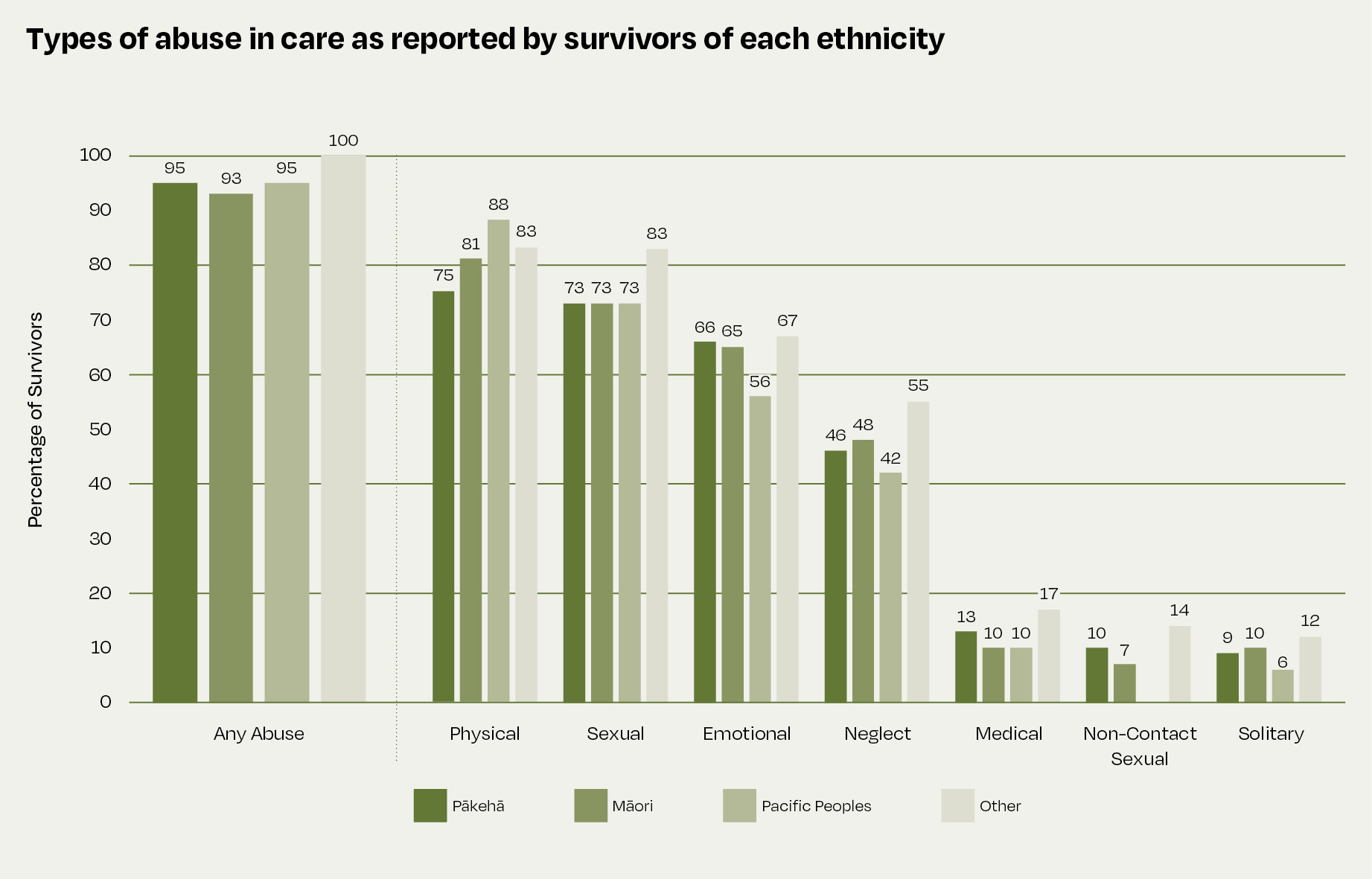

1064.Where possible, this chapter will highlight where the extent of abuse or neglect within a given setting disproportionately applies to tamariki and rangatahi Māori. The graph below shows analysis by DOT of the types of abuse and neglect reported by survivors of each ethnicity. Ethnicities include Pacific Peoples, Māori, Pākehā and other, which includes Middle Eastern, Latin American, African, Asian, other ethnicity, survivors who preferred not to say, and where the data is not known.[1452]

Types of abuse in care as reported by survivors of each ethnicity

1065. Notably, the MartinJenkins report was unable to reach any conclusions regarding the proportion of survivors of abuse who are Māori or Pacific Peoples given the lack of recorded ethnicity data for people in care throughout this Inquiry’s scope period.

1065. Notably, the MartinJenkins report was unable to reach any conclusions regarding the proportion of survivors of abuse who are Māori or Pacific Peoples given the lack of recorded ethnicity data for people in care throughout this Inquiry’s scope period.

Te rangiwhāwhātanga o te tūkinotanga i roto i ngā whakaritenga taurima rerekē

Prevalence of abuse in different care settings

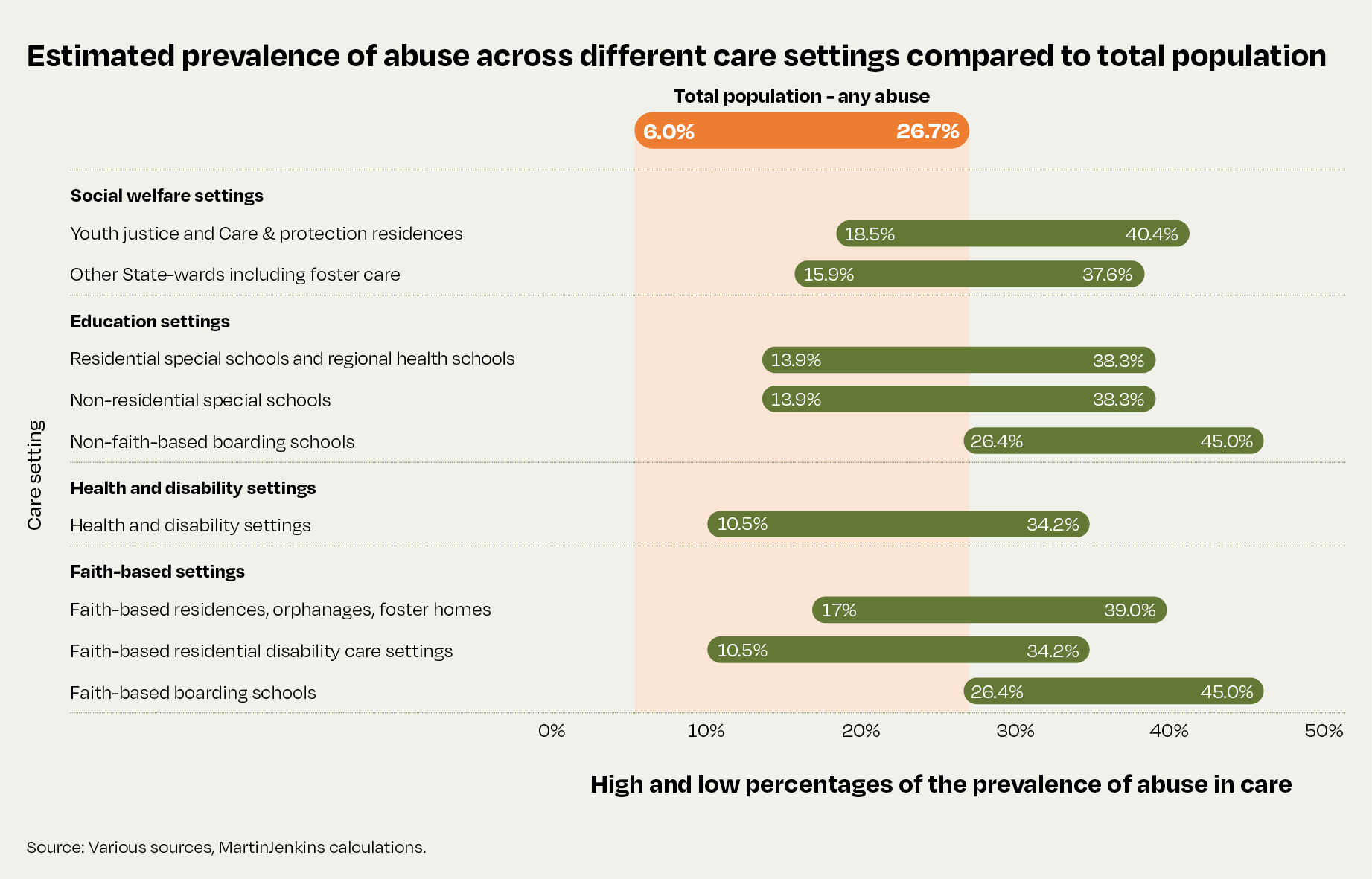

1066.Drawing on research used in the MartinJenkins report, it is evident that estimates of the extent or prevalence of abuse differ between settings, and that abuse occurred at all settings the Inquiry investigated. These prevalence estimates are probably lower than the figures of survivors who spoke to the Inquiry, as this is a self-selecting group who were more likely to have been abused, as they engaged with the Inquiry. The graph below shows the high and low estimates of the extent of abuse between different settings:[1453]

Estimated prevalence of abuse across different care settings compared to total population

Ngā ngoikoretanga o te mātauranga mō ngā whakaritenga taurima katoa

Ngā ngoikoretanga o te mātauranga mō ngā whakaritenga taurima katoa

Limitations to knowledge for all care settings

1067. Understanding the extent of historical (and contemporary) abuse and neglect in care settings is a challenge around the world. The limitations for determining the nature and extent of abuse and neglect in Aotearoa New Zealand reflects international reviews on the historical abuse of children and adults in care. The information available to the Inquiry regarding the extent of abuse and neglect is limited across most care settings, as well as being recorded inconsistently across settings of different types.

1068. Reasons for these limitations that impact on understanding the extent and prevalence of abuse and neglect include:

- Under-reporting (also known as dark-figure) – under-reporting of abuse and neglect is common and occurs for many different reasons including lack of trust in authority, fear of not being believed or of being punished, dependence on the abuser for support, the person was isolated and it was difficult for them to tell anyone, the person did not know who to tell or how to get help, in some cases the person may not recognise abusive or neglectful behaviour as abnormal as the abuse/neglect was common and perceived it as a normal part of life, shame and trauma.

- Delayed reporting – this is common, with many children and young people unable to report abuse until they are adults or adults in care not reporting until they left institutional care settings. The reasons are similar to those for underreporting, and include fear of repercussions, particularly if the abuser is in a position of authority. The Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse reported that Catholic Church claims data showed a 30-year or more gap in 59 percent of the claims between the first alleged incident of child sexual abuse and the date when the claim was received by the Catholic Church authority and a 20-year or more gap in 81 percent of claims.[1454]

- Unrecorded reporting (also known as ‘grey figure’) – this is when a report is made but is not recorded adequately, either for accidental or deliberate reasons.

- Reports and information being obstructed – in State and faith-based care (including direct and indirect) institutions, information was often intentionally not gathered by those in positions of responsibility and leadership. Documents have also been purposefully destroyed and data has not been written and formalised, as a means of self-protection.

- Issues with accuracy of the information – reasons for this include the nature of reporting being potentially stressful, traumatic childhood experiences, and the method of assessment. Additionally, surveys may not collect information from people who are unable to consent to, or complete, the survey without assistance, including people with low English language proficiency, communication difficulties and differences or learning disabilities where no or limited reasonable accommodations were offered.

- Ethical considerations–there are ethical considerations in asking children, young people and disabled adults if they have been abused or neglected. For this reason, at-risk populations are often not included in population-based research.

1069.The MartinJenkins report and a peer-review of the same, identified similar limitations that apply to the report’s methodology and estimates.[1455]

Te pupuringa rekoatatanga i ngā whare Kāwanatanga

Institutional record keeping

1070. Information collection across all State and faith-based care (including direct and indirect) institutions has been poor and inconsistent. Some specific issues around recording extent are discussed in this section and are expanded upon in Part 6 of this report.

Ngā whakaritenga taurima tokoora

Social welfare care settings

1071. Information collection processes of Oranga Tamariki and its predecessors have been, and remain, unsatisfactory.

1072. In response to the Inquiry’s Notice to Produce regarding their record keeping, Oranga Tamariki stated that their data on the number of children who were in care from 1950 to1999, and number of allegations of abuse or neglect which were recorded for any stage during this period, were not reported and recorded at an aggregate level. Oranga Tamariki accepted that:[1456]

a. There have been occasions where children and young people have disclosed allegations of abuse which went unheard. As a result, these have not been recorded or formally responded to.

b. When allegations/disclosures have been responded to, there have been occasions when these allegations/disclosures were not formally recorded.

c. Even when allegations/disclosures have been responded to and recorded, these cannot be reported at an aggregate level.

1073. It was further noted that information on allegations of abuse, subsequent investigation and assessment, and outcomes, from 1950 to 2010, “cannot be reported without reviewing each individual case file”.[1457] Similarly, “there is no available information on the breakdown in ethnicity of children in care prior to 2001”, as the information was held on individual case files.[1458]

1074. The lack of data regarding complaints is further supported by evidence from former staff. Gary Hermansson, who spent time as a manager and counsellor at Epuni Boys' Home, Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai Lower Hutt and Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre, Taitoko Levin during the 1960s and 1970s, shared how there was ‘no formalised complaints system’ and informal complaints were also not recorded.[1459]

1075. This approach to complaints probably contributed towards the significant ‘grey figure’ of abuse that was reported by survivors but cannot be seen in any official statistics, representing missed opportunities for safeguarding residents or preventing abuse.[1460]

1076. Oranga Tamariki was questioned regarding the 2022 report of the Independent Children’s Monitor, which stated that Oranga Tamariki was only able to provide data for “5 percent of the 199 measures for all children in their care using its database.”[1461] This is discussed further in Part 1 of this report. Nicolette Dickson, an Oranga Tamariki director, agreed that this limitation in terms of the data they had available to report on these standards was "a problem".[1462] Oranga Tamariki advised that work was ongoing to improve information collection processes.

Ngā whakaritenga ā-whakapono

Faith-based care settings

1077.There is no reliable figure on the extent of abuse in Aotearoa New Zealand’s faith-based care during the Inquiry period. As discussed in the Inquiry’s interim report He Purapura Ora, he Māra Tipu, From Redress to Puretumu Torowhānui[1463] faith-based institutions were found to have poor access to information and record-keeping processes. This included where information was withheld from survivors, accidentally or deliberately destroyed by the institution, lost, incorrectly recorded and incomplete.

Ngā whakaritenga taurima ā-whaikaha

Disability care settings

1078. Like other care settings, poor practices in recording incidents of abuse, neglect, and complaints mean the Inquiry cannot quantify how many people in disability care settings were abused, to what extent they were harmed, by whom, and when. This lack of information means the Inquiry has no figures to show how people in care were targeted because of their disability, gender, ethnicity, cultural practices, or sexual orientation. While numbers would help Aotearoa New Zealand understand the prevalence of abuse and neglect in State and faith-based care settings, these remain unknown. The Inquiry must rely on the evidence of the many survivors it heard from.

1079.Drawing conclusions from international studies examining the prevalence of Deaf and disabled people experiencing abuse and neglect in psychopaedic care settings is problematic. There are very few studies that examine abuse and neglect of Deaf and disabled people in care or in institutions. Those that do exist differ in the population studied (by gender, age and type of impairment) and the type of abuse and neglect, making comparisons difficult.

1080.Most studies are not ethnically diverse or do not report on ethnicity. They rarely specify the age of the participant when they were abused. Further, since prevalence is linked to reporting, Deaf and disabled people could be less likely to report abuse and/or neglect, for example due to communication barriers. Deaf and disabled people are both under-represented and undercounted in research studies.[1464]

Mātauranga

Education

1081.Existing research and reviews in Aotearoa New Zealand regarding the extent of abuse in education settings is limited. While there is national reporting on peer-to-peer violence and bullying in education settings, there is very little reporting on abuse and misconduct perpetrated by staff or volunteers in education settings.

Te whakarāpopototanga o ngā ngoikoretanga

Summary of limitations

1082. Given these challenges and others discussed throughout this report, there is inevitably a wide range of uncertainty around any estimates of the groups and of the numbers of survivors of abuse. The ‘true’ number of people in care and number of survivors of abuse since in Aotearoa New Zealand could never be known with any degree of precision.

1083. There are similarities between the findings of international inquiries and reviews, and accounts of New Zealanders who were in care. The accounts of survivors suggest that physical, sexual, emotional abuse and neglect were widespread in certain care settings.

1084. Potentially most, if not all of those, who resided in these care settings either experienced or witnessed some type of abuse and neglect. Therefore, the prevalence rate within such a care setting could arguably be as high as 100 percent.

Te roanga o te tūkinotanga i te taurima ā-tokoora

Extent of abuse in social welfare care

Te whakatau tata o te taupori

Estimated population

1085.In this section, social welfare care refers all social welfare placements, as well as people in care and protection residences and foster care.

1086.MartinJenkins estimated how many people probably experienced abuse in social welfare care settings from 1950 to 1999. This estimate is based on data supplied from the Inquiry’s survivor database, as well as prevalence data from international studies of abuse in similar settings overseas. Their analysis of available data provided a low estimate of 30,051 survivors (16.8 percent of survivors who experienced these settings from 1950 to 2019), as well as a high estimate of 69,008 survivors (38.6 percent).[1465]

Ngā rangahau, ngā ripoatatanga rānei mō te whānuitanga o te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

Research or reporting on the extent of abuse and neglect

1087. Chappie Te Kani, Chief Executive of Oranga Tamariki and Secretary for Children, accepted at the Inquiry's State Institutional Response Hearing that even without exact prevalence data, the extent of sexual abuse that has been reported within social welfare residences and institutions is so significant that it should be considered a systemic problem.[1466]

1088. Professor Elizabeth Stanley provided quantitative evidence regarding the extent of abuse from her book Road to Hell at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing. This included that 91 percent of the 105 institutional survivors in her book suffered “serious physical violence” from staff in institutional care, with all survivors witnessing others being physically attacked by staff.[1467]

1089. Professor Stanley’s evidence also emphasised that violence was ‘endemic’ in social welfare settings. She explained that children endured “daily denigrations” that were “part of the everyday administration of the care system.[1468] Survivors accounts of the scale and routine nature of abuse in social welfare care help illustrate the extent of abuse experienced in these settings.

1090. In terms of sexual abuse in social welfare residences and institutions, abuse was not just perpetrated by a few ‘bad apples’ but by multiple abusers sometimes operating within the same institutions simultaneously, some of whom sexually abused large numbers of children over significant periods.

1091. One study commissioned for the former Department of Social Welfare, and published in 1987, found that 71 percent of a sample of 15-year-old State wards had experienced sexual abuse, with 40 percent of those experiencing abuse after entering care. In a sample of 239 girls, 11 percent had been sexually abused by members of their own foster family.[1469]

1092. The Ministry of Social Development received more historic claims for sexual abuse relating to Epuni than any other social welfare residence over the Inquiry period.[1470] Analysis of its records shows that some survivors were sexually abused multiple times by multiple staff members at Epuni.[1471] Ministry of Social Development records also show that sexual abuse by Epuni staff was particularly widespread from 1968 to 1978, with 68 allegations made by 32 claimants.[1472]

1093. In a 1987 study of 136 young women in residential care (social welfare, youth justice and foster care) that was conducted by the Department of Social Welfare, 70 percent of participants said they had been sexually abused, half of them while in institutional or foster care.[1473]

1094. Most children and young people also experienced secure cells during their placements in social welfare institutions. The Department of Social Welfare records show 90 percent of children in social welfare residences and institutions in 1986 had been in secure cells.[1474] This was often part of the induction process for new arrivals. For example, during the 1970s, Weymouth Girls' Home in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland placed every new arrival in secure cells, sometimes for up to two weeks.[1475] Expert witness Dr Oliver Sutherland notes that:

“These children were in fact held in prison conditions without having been committed by any judicial process and without any use of the safeguards afforded prisoners in a penal institution.”[1476]

1095. Several investigations and reports on social welfare institutions have found similar incidents of abuse and neglect. A 1979 report by ACORD, Ngā Tamatoa and Arohanui Inc, found that social welfare residences and institutions were prison-like, and that children were subjected to cruel and inhumane treatment such as violence and assaults, psychological abuse, isolation in secure units, and forced internal examinations for sexually transmitted infections.[1477] Survivors recalled physical examinations being done by force and used as a punishment.[1478]

1096. The Confidential Listening and Assistance Service (CLAS) was set up to hear from those who were in any type of State care up to 1992, if they had concerns or allegations regarding abuse or neglect during their time in care.[1479] Reports of abuse in social welfare residences and institutions and foster care were among those disclosed to CLAS. The final report included that:

“Policy in Boys’ and Girls’ Homes seemed to support a system of institutional bullying. This bullying was done by some staff members and the older residents. Not all staff were violence or abusive, but they seemed to turn a blind eye to what went on. The abuse suffered by a young person entering such a ‘home’ could be verbal or emotional or physical or sexual, or all of these. Children learnt to fight to survive; and were sometimes made to fight for the amusement of staff.”[1480]

1097. The Christchurch Health and Development Study, a longitudinal study of more than 1,000 children born in the mid-1970s, showed an increased extent of frequent, severe physical abuse among those who experienced care aged 16 years old and younger.[1481] Māori (55 percent of total children) and European / other (34 percent of total children) also experienced increased physical violence compared to Māori and European/other children who were never in care (25 percent and 13 percent respectively).

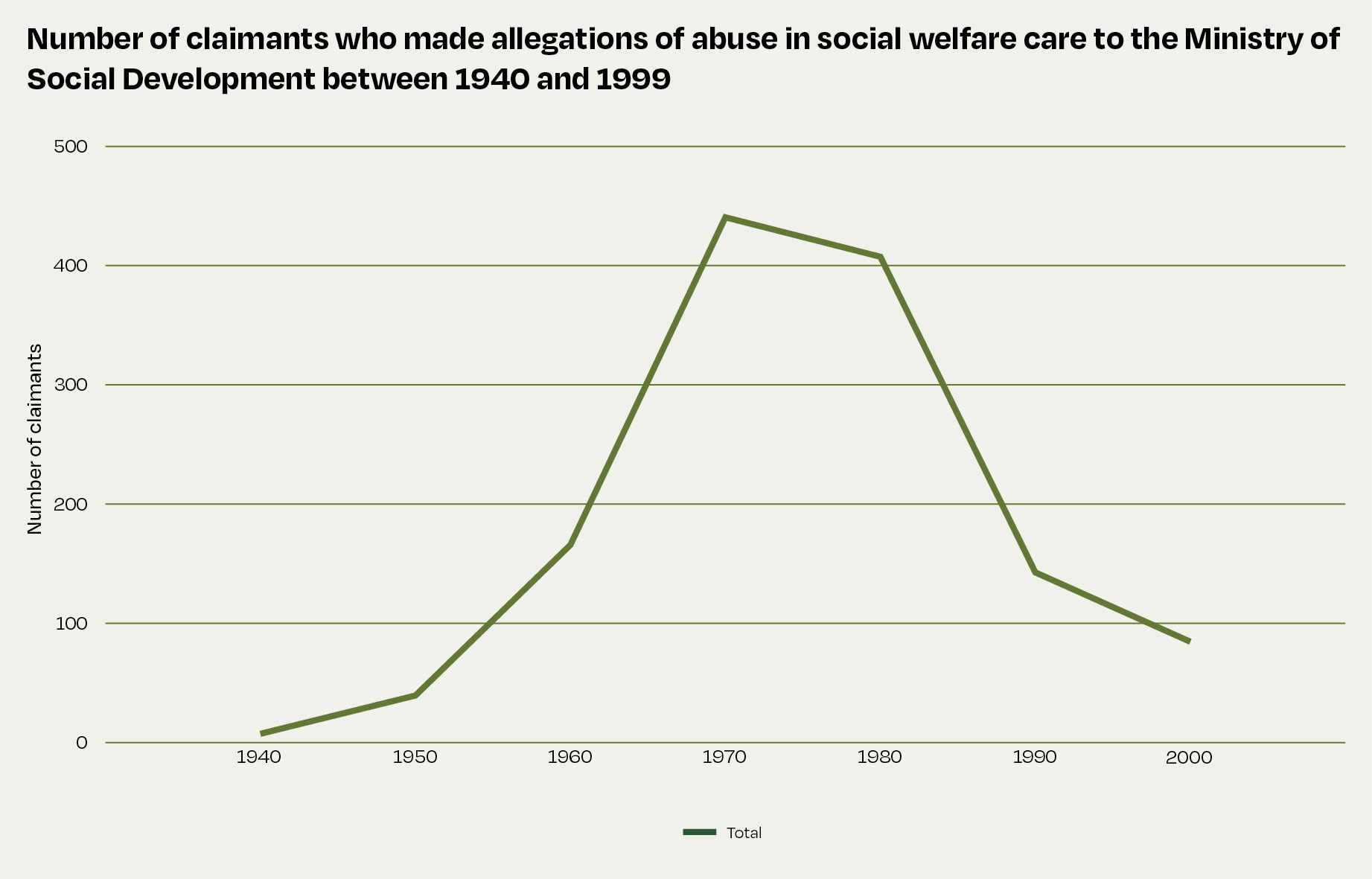

1098. The Inquiry carried out some basic quantitative analysis of data provided by the Ministry of Social Development. Analysis of this data supports the claim that the extent of abuse incidents was probably at its highest during the 1970s and 1980s. The graph below illustrates the number of claimants who have made allegations of abuse in social welfare care to the Ministry of Social Development between the years of 1940 to 1999:[1482]

Number of claimants who made allegations of abuse in social welfare care to the Ministry of Social Development between 1940 and 1999

1099. The basic quantitative analysis of historic claim applications also provides context regarding the extent of abuse in care, including when and where these incidents occurred, what role the abuser played within the State system or how they encountered children and young people. Claims applications provided to this Inquiry included 7014 allegations of abuse, and 1490 instances of ‘practice failure’ from 1263 unique claimants.[1483]

1099. The basic quantitative analysis of historic claim applications also provides context regarding the extent of abuse in care, including when and where these incidents occurred, what role the abuser played within the State system or how they encountered children and young people. Claims applications provided to this Inquiry included 7014 allegations of abuse, and 1490 instances of ‘practice failure’ from 1263 unique claimants.[1483]

1100. The settings with the most abuse allegations were Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre, Taitoko Levin Boys’ Home (793 claims from 226 claimants) and Epuni Boys' Home, Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai Lower Hutt (779 claims from 206 claimants).[1484]

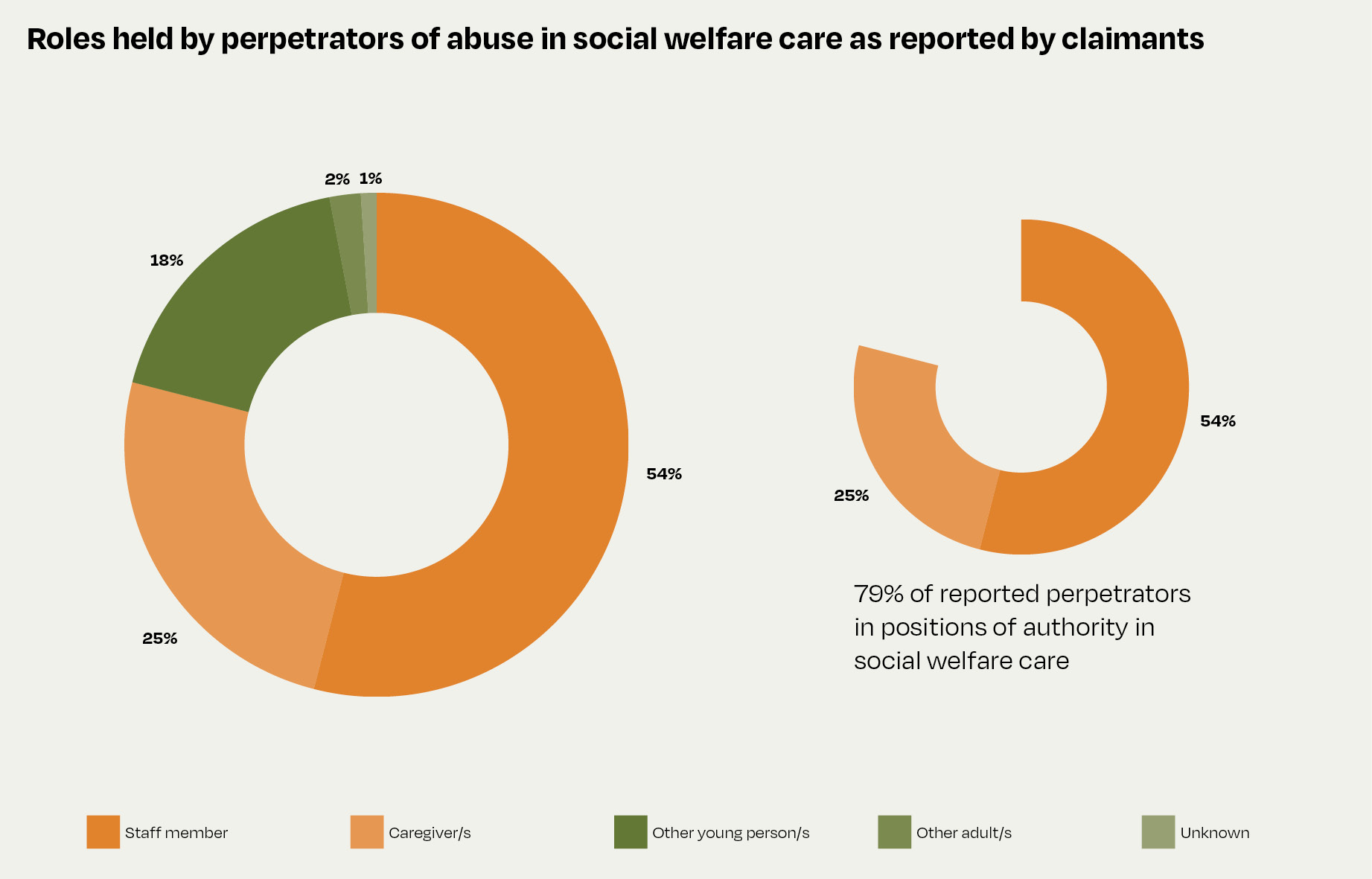

1101. In relation to more than 1,400 abuse incidents with an identified abuser, the ` claimants reported that their abuser was a ‘staff member’ in the majority of incidents (793), with the next most common being a caregiver (365) or another young person (270). A comparison of the types of roles abusers held when abuse occurred, if the survivor identified an abuser, is shown below:[1485]

Roles held by abusers of abuse in social welfare care as reported by claimants

1102. By October 2022, the Ministry of Social Development historic claims team had received more than 1,000 allegations of sexual abuse in social welfare settings.[1486]

1102. By October 2022, the Ministry of Social Development historic claims team had received more than 1,000 allegations of sexual abuse in social welfare settings.[1486]

1103. There is little evidence available regarding the extent of abuse and neglect in foster care in Aotearoa New Zealand. CLAS’s final report found that children were often placed with unsuitable foster families.[1487] Some of these foster parents had high social standing but were abusive and neglectful behind closed doors.[1488] While figures regarding alleged and substantiated abuse could exist in individual records, it is unclear how representative they would be in terms of actual abuse experienced in foster care.

1104. Recent figures regarding children and young people in Oranga Tamariki’s care from July 2018 and June 2019 indicated that there were 707 substantiated harm incidents involving 464 children and young people (5.65 percent of those in care), including 200 substantiated findings of harm in non-family placements such as foster care.[1489]

1105. These figures included 82 findings of physical harm against 63 survivors, with 65 of these incidents occurring within the placement. There were 48 findings of sexual harm (43 survivors), with 15 incidents occurring within the placement. There were 63 findings of emotional harm (45 survivors), with 53 of the incidents occurring within the placement. Oranga Tamariki also recorded seven cases of neglect.[1490]

Ngā purapura ora i kōrero ki te Kōmihana mō te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

Survivors who spoke to the Inquiry about abuse and neglect

1106. The Inquiry received evidence from more than 1,300 survivors which included abuse in social welfare settings such as boys’ homes, girls’ homes and foster care. Across all survivors, physical abuse was the most commonly experienced type, reported in 57 percent of accounts. The next most common abuse types were sexual (51 percent) and emotional (46 percent).[1491]

1107. Māori were disproportionately represented in the care system throughout the Inquiry period, particularly in the case of social welfare settings such as boys’ and girls’ homes. The Inquiry also heard how Māori survivors were racially targeted by abusers, or otherwise subjected to disproportionate abuse while in care.

1108. These ideas are supported by what the Inquiry heard from Māori about the extent of abuse and neglect they suffered. Of the Māori survivors who went through social welfare settings, 60 percent reported experiencing physical abuse. The next most common types of abuse by Māori survivors in these settings were sexual abuse (53 percent) and emotional abuse (49 percent).[1492]

1109. Looking specifically at female Māori survivors, the most experienced type of abuse for those in social welfare care was sexual abuse, which was reported by 57 percent. The next most common types were physical abuse (56 percent), and emotional abuse (53 percent).

1110. Pacific survivors in social welfare settings experienced the highest proportion of physical abuse for any ethnicity or setting: 63 percent. In addition, more than half of Pacific survivors who spoke to the Inquiry described being sexually abused while they were in social welfare care (52 percent).

1111. Pākehā was the most frequently recorded ethnicity among survivors who spoke to the Inquiry. Looking at social welfare settings, the most frequent type of abuse for Pākehā survivors was physical abuse (54 percent), closely followed by sexual abuse (50 percent).

1112. For survivors who identified as having any kind of disability, the most reported type of abuse in social welfare care was physical abuse (55 percent). The next most common types were sexual abuse (46 percent), and emotional abuse (45 percent).[1493] In addition, 30 percent of disabled survivors said they were neglected while in social welfare settings.

1113. Of survivors who had difficulty learning, 53 percent were physically abused in social welfare settings, while 47 percent were sexually abused and 43 percent were emotionally abused.[1494]

1114. The type of abuse most reported by survivors who have a communication disability was physical abuse, which was included in 59 percent of accounts. In addition, half of these survivors experienced emotional abuse (50 percent), and 45 percent were sexually abused.[1495]

1115. According to DOT Loves Data analysis, across State settings, foster care had the highest proportion of reported sexual abuse.[1496]

1116. The type of abuse most commonly experienced by survivors who have a mobility impairment was physical abuse, which occurred in 63 percent of these accounts. The next most common types were sexual abuse (52 percent) and emotional abuse (51 percent). The fact that the majority of mobility impaired survivors who spoke to the Inquiry experienced each of these types of abuse is damning evidence of the level of care these survivors received, in a situation where they were highly reliant on staff and caregivers to meet their needs. In addition to this overt abuse, 36 percent of mobility impaired survivors reported being neglected in these settings.

1117. For survivors with any kind of neurodivergence, more than half of those who experienced social welfare care were physically abused.[1497] In addition, 41 percent were emotionally abused and 41 percent were sexually abused.

1118. More than half of the blind survivors who spoke to the Inquiry about their experience in social welfare care settings were physically abused (53 percent).[1498] The next most common types of abuse in social welfare settings were sexual (44 percent), and emotional (36 percent).[1499] In addition, 28 percent of blind survivors were neglected in these settings.

1119. For Deaf survivors, physical abuse was the most common type of abuse experienced (61 percent). The next most common types were emotional abuse (48 percent), and sexual abuse (40 percent).[1500] In addition, 34 percent of Deaf survivors who experienced social welfare settings were neglected while they were there.

1120. More than 1,000 survivors who experienced mental distress and spent time in social welfare settings gave evidence to the Inquiry. Of this group, the abuse type most common was physical abuse (56 percent) with sexual abuse and emotional abuse, at 52 percent and 46 percent respectively.[1501]

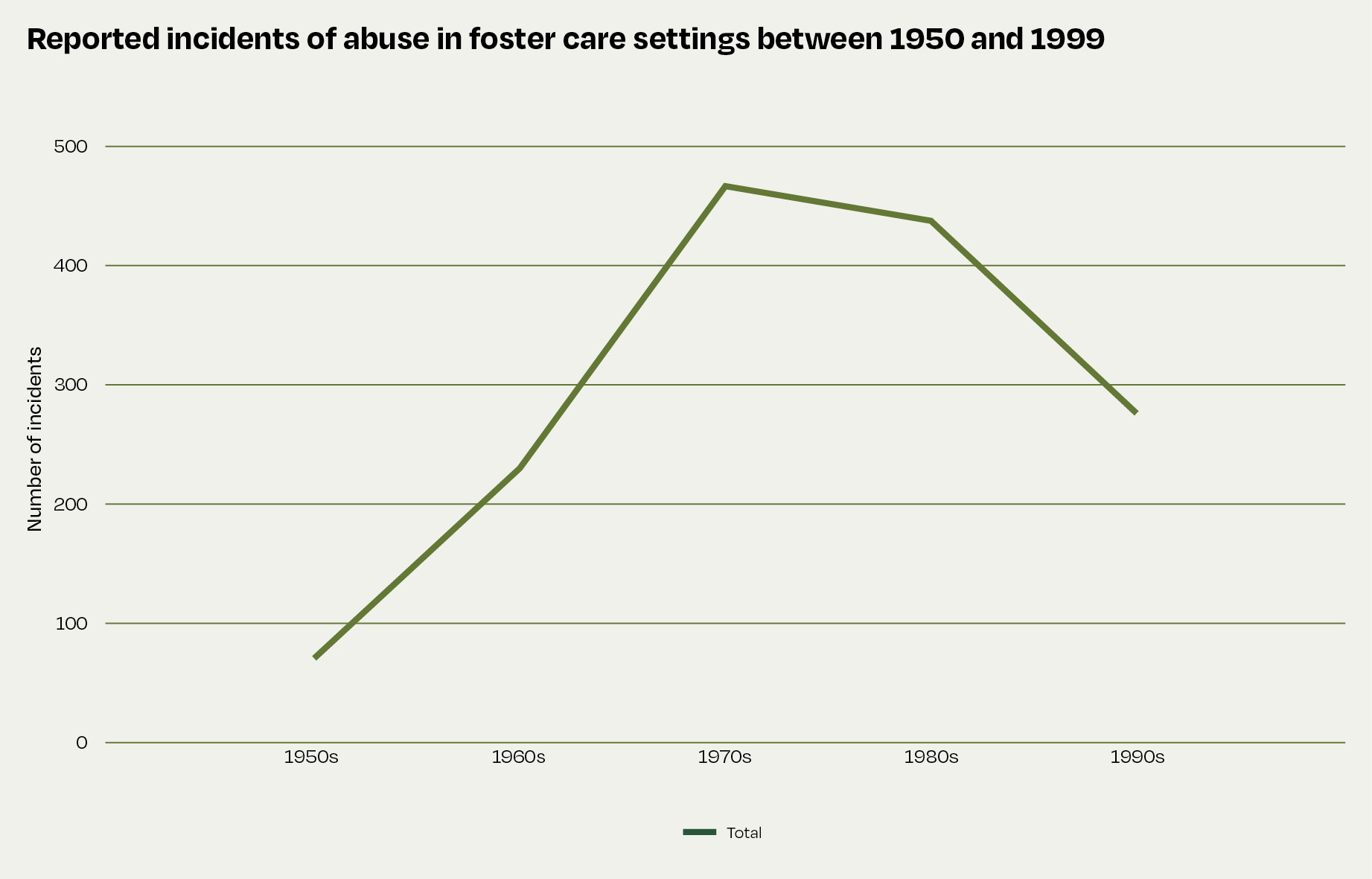

1121. DOT Loves Data analysis of accounts survivors shared with the Inquiry indicated foster care was the setting where the highest proportion of survivors experienced abuse (715 survivor accounts, with 1,108 incidents).[1502] While these reports of abuse and neglect provide useful information on what happened in these settings, they cannot be used to determine the true extent of abuse throughout the foster care system from 1950 to 1999.

1122. The graph below shows the chronological spread of abuse incidents in foster care reported to the Inquiry, based on analysis by DOT:[1503]

Reported incidents of abuse in foster care settings between 1950 and 1999

Te rangahau ā-ao whānui mō te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

Te rangahau ā-ao whānui mō te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

International research on abuse and neglect

1123.International literature on abuse in foster settings includes a 1999 UK study of 133 children who were fostered or in residential care over a six-year period, which found that 158 episodes of alleged physical or sexual abuse were assessed and reported by a paediatrician, with 41 percent involving foster carers as the abuser and 20 percent involving other children.[1504]

Te roanga o te tūkinotanga i roto i te pūnaha taurima a-whakapono

Extent of abuse in faith-based care

Te whakatau tata o te taupori

Estimated population

1124. The MartinJenkins report, which used the timeframe of 1950 to 2019, estimated that approximately 254,000 people were in faith-based care settings (excluding pastoral care) over the Inquiry’s scope period. Of this number, 143,000 (56 percent) were in faith-based children’s homes, orphanages, and foster homes; 1,600 (0.6 percent) were in faith-based residential disability care settings; and 109,000 (43 percent) were in faith-based boarding schools.[1505]

1125. MartinJenkins also determined how many people probably experienced abuse in faith-based care settings. Their analysis of available data provided a low estimate of 53,388 (21 percent of the survivors who experienced these settings from 1950 to 2019), as well as a high estimate of 105,713 (41.6 percent).[1506] The report also confirmed that faith-based settings probably had the highest prevalence of abuse, with 33 to 38 percent of those who experienced these settings probably abused.[1507]

Ngā rangahau, ngā ripoatatanga rānei mō te whānuitanga o te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

Research or reporting on the extent of abuse and neglect

1126. The Inquiry is not aware of any research conducted to try to understand the extent of abuse and neglect across faith-based care settings in Aotearoa New Zealand.

1127. However, some churches have undertaken exercises to understand the size of the problem within their own faith. Te Rōpū Tautoko (Catholic) as part of its Information Gathering Project, analysed information provided by Catholic entities. From 1950 to 2022, Te Rōpū Tautoko (Catholic) found a total of 7,807 diocesan clergy and religious present in Aotearoa New Zealand, and a total of 1,680 reports of alleged abuse held by church entities. These reports of abuse were made against 1,122 individual clergy members- 14.4 percent of the total number from 1950 to 2022.[1508]

Ngā purapura ora i kōrero ki te Kōmihana mō te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

Survivors who spoke to the Inquiry about abuse and neglect

1128. The Inquiry heard from more than 800 survivors who had experienced abuse and neglect while in the care of faith-based institutions.[1509] Analysis of accounts from survivors of faith-based care showed that the abuse types most commonly experienced varied between different groups, as discussed below. Sexual abuse was the most commonly experienced type in this setting (48 percent), followed by emotional abuse (40 percent) and physical abuse (38 percent).[1510]

1129. Sexual abuse was found to be more prevalent in faith-based settings as opposed to State settings, in particular at Dilworth School (Anglican) and Marylands School (Catholic).[1511] In addition, more than half of survivors who provided evidence to the Inquiry after going through a Catholic institutional setting were sexually abused.[1512]

1130. The Inquiry spoke to more than 200 Māori survivors of faith-based care settings.[1513] More than 200 Māori survivors who spoke to the Inquiry experienced faith-based care.More than a third of these survivors experienced sexual (39 percent, physical (39 percent) and emotional abuse (34 percent).[1514] Of wāhine Māori who spoke to the Inquiry about their time in faith-based settings 41 percent were sexually abused while they were there, making it the most common abuse type for this group. The next most common types were physical and emotional abuse at 39 percent and 37 percent respectively.[1515]

1131. For Pacific survivors in faith-based settings, the most frequently experienced types of abuse were physical (45 percent) and sexual (33 percent).[1516]

1132. Within faith-based settings, almost half of the Pākehā survivors who gave evidence to the Inquiry were sexually abused (49 percent). This and other similar figures that emerge from DOT Loves Data analysis indicate that the extent of sexual abuse was a systemic problem across different faith-based settings, rather than the result of ‘a few bad apples’.

1133. Within faith-based settings, survivors with a disability gave evidence that sexual abuse was the most frequently experienced type, as reported by 41 percent of the group. The next most common types were physical abuse and emotional abuse, both at 37 percent of accounts.[1517]

1134. For survivors who had a learning disability and were placed in faith-based settings 44 percent were sexually abused while they were there.[1518] The next most common types were physical abuse (41 percent), and emotional abuse (39 percent).

1135. Within faith-based settings, almost half of survivors with a mobility impairment were sexually abused (45 percent). In addition, 31 percent were physically abused in these settings, while 29 percent gave evidence of being emotionally abused.[1519]

1136. A quarter of survivors with a communication disability were sexually abused while in faith-based care.[1520]

1137. Of blind survivors who were in faith-based settings, the most common type of abuse was emotional (58 percent). The next most common types were physical abuse and sexual abuse, which were in 53 percent of accounts.[1521]

1138. Within faith-based settings, the type of abuse most commonly experienced by Deaf survivors was sexual abuse (38 percent). The next most common types were emotional and physical abuse, which each featured in 35 percent of accounts from Deaf survivors.[1522]

1139. For mentally distressed survivors who were in faith-based settings, the most common type of abuse was sexual abuse, which was in 49 percent of accounts.

Ngā taunakitanga ā-ao whānui mō te whānuitanga o te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

International sources on the extent of abuse and neglect

1140. Research on the extent of different types of abuse in faith-based institutions is lacking, however international abuse inquiries can provide some relevant insights, including: the 2019 UK and Wales Royal Commission; the 2019 Historic Institutional Abuse Inquiry in Northern Ireland; the 2011 Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse in the Republic of Ireland; and a 2017 research review of the Scottish Royal Commission.

1141. International literature shows that male religious leaders and others are more likely to sexually abuse than females.[1523] However, most of the inquiries listed above[1524] found several church institutions where nuns and other females were physically and emotionally abusive, as well as being aware of priests sexually abusing children without reporting this to non-church authorities.

1142. A study of a German government hotline set up for survivors to anonymously disclose their experiences of sexual abuse found that of 1,050 survivors, 404 had been in Roman Catholic, 130 in Protestant and 516 in non-religious institutions.[1525] In addition, most victims reported that the abuse had occurred repeatedly, that the assaults had been committed by males and sexual intercourse was more frequently reported at the time of abuse by older victims and by females.[1526]

1143. A recent UK child sex abuse inquiry found that 85 percent of survivors abused in a religious context told someone about the abuse after it ended, in line with the 82 percent of survivors who made a disclosure after being abused in a non-religious context.[1527] When disclosing abuse as a child, survivors who were sexually abused in religious contexts often only reported their abuse to someone in authority inside the institution.

1144. Overseas inquiries and US research show similarities in the extent of abuse in faith-based institutions to non-religious organisations, and that precise estimations of prevalence could be impossible due to under-reporting of abuse,[1528] or significant delays in disclosing abuse (often when abused children become adults).[1529] Overseas inquiries also found that religious leaders’ responses to reports of abuse, within faith-based institutions, have been to keep investigations ‘in-house’,[1530] which presents significant challenges for survivors who attempt to bring their abusers and the institutions responsible for them to justice.

1145. The UK Inquiry 2019 report summarised the outcomes for abusers of reports made at the time of the abuse. These involved:[1531]

- religious leaders questioning abusers, but after abusers gave reassurances, they remained in their positions or were given positions of further responsibility

- religious leaders not reporting abuse allegations to the police nor escalating them to higher levels within churches or religious communities

- the abusers being moved elsewhere but remaining working in the organisation.

1146. For survivors abused in religious contexts who reported child sexual abuse after it had ended, 60 percent said that they had also disclosed to police at the time the abuse was occurring (by comparison, 54 percent of survivors reporting abuse in a non-religious context disclosed to the police). When disclosing the abuse after it had ended, survivors told a variety of other people, including staff in mental health services, family members, and partners.[1532]

Te roanga o te tūkinotanga i roto i te pūnaha hauora Turi, whaikaha, mate hinengaro, whaiora hoki

Extent of abuse in Deaf, disability, psychiatric, psychopaedic and mental health care

Te whakatau tata o te taupori

Estimated population

1147. In preparation of its estimates MartinJenkins included psychiatric hospitals or special and restricted facilities. It did not include other Deaf, disabled and mental distress facilities such as special schools (included within the education estimates below) or health camps.

1148. MartinJenkins estimated a total of 183,489 people in the identified health and disability care settings. The MartinJenkins report further estimates how many people probably experienced abuse in health and disability care settings. Their analysis of available data from international studies provided a low estimate of 22,153 survivors (10.5 percent of survivors who were in these settings from 1950 to 2019), and a high estimate of 72,422 survivors (34.2 percent).[1533]

Ngā rangahau, ngā ripoatatanga rānei mō te whānuitanga o te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

Research or reporting on the extent of abuse and neglect

1149. There has been limited research done on the extent of abuse and neglect in Deaf, disability, psychiatric and mental health care settings. The Ministry of Health has never kept centralised records. As part of its Notice to Produce response, the Ministry of Health reported that any complaints of abuse that could have come to the attention of the Ministry and its predecessors over the scope period would not be held in a central location and would instead be held among records for the relevant directorate or business unit.[1534] The Ministry stated it was not a health provider and so was unable to answer questions relating to records.[1535]

1150. The Inquiry is not aware of any national-level research undertaken by any other State department.

1151. At the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing, Ministry of Health representative Director-General of Health Dr Diana Sarfati acknowledged that “many disabled people placed in care settings experienced abuse and other forms of harm.”[1536]

Ngā purapura ora i kōrero ki te Kōmihana mō te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

Survivors who spoke to the Inquiry about abuse and neglect

1152. For Pākehā survivors of disability and mental health settings, the most commonly experienced type of abuse was physical, at 44 percent.

1153. For those with a disability who were in disability or mental health care settings, physical abuse was experienced by 41 percent. Also, frequently experienced were sexual abuse (40 percent), emotional abuse (35 percent), and neglect (20 percent).

1154. Of those who had a learning disability, 46 percent gave evidence about being physically abused, 43 percent were sexually abused, and 38 percent emotionally abused.[1537] As for education-based settings, more than half of survivors with a learning disability who experienced these settings were emotionally abused.

1155. In terms of neurodiverse survivors in these settings, 40 percent experienced physical abuse and the same proportion experienced sexual abuse.[1538]

1156. Among survivors who have a mobility impairment, 38 percent shared experiences of sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and physical abuse. In addition, 30 percent of the mobility impaired group were neglected while in disability and mental health care settings.[1539]

1157. For survivors who had a communication disability and experienced dedicated disability and mental health settings, the most common type of abuse was emotional (44 percent). In addition, 31 percent of communication impaired survivors were physically abused and the same proportion were sexually abused.[1540]

1158. For blind survivors, 47 percent were physically abused, while 33 percent were sexually abused.[1541]

1159. Looking at survivors with chronic health conditions, physical abuse was the type most commonly experienced (43 percent), followed by emotional abuse (38 percent), and sexual abuse (35 percent).

1160. For survivors who experienced mental distress, the most common abuse type in these settings was physical, which featured in 43 percent of accounts.

1161. Almost half of Māori survivors who went through disability or mental health care settings were physically abused (46 percent). There was also significant sexual (33 percent of accounts), and emotional abuse (31 percent of accounts) experienced by Māori.[1542]

1162. For wāhine Māori who spent time in dedicated mental health and disability care settings, physical abuse was the most commonly experienced type (44 percent).

1163. Of the Pacific survivors who experienced disability or mental health settings 36 percent said that they were neglected while they were there. This is a high proportion compared to other groups or settings. The next most common abuse type was physical abuse, which was experienced by 29 percent of survivors.

1164. The Inquiry also analysed the extent of abuse it heard about from Deaf survivors during the Inquiry period. For those who experienced dedicated disability and mental health settings, physical abuse was the most common type and featured in 57 percent of survivor accounts.[1543] The next most common types were emotional abuse and sexual abuse, which each featured in 48 percent of accounts.

1165. The Inquiry heard from more than 300 survivors who experienced abuse in a psychiatric institution in Aotearoa New Zealand.[1544] In addition, experts and former staff witnesses discussed their experiences of working in these settings or the experiences of a loved one who had been in a psychiatric setting.

Te rangahau ā-ao whānui mō te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

International research on abuse and neglect

1166. Studies conducted since the 1960s have found that disabled children are at significantly greater risk of abuse and neglect.[1545] However, disabled children’s risk of abuse was not brought to public notice until the 1980s when US and Canadian studies found that disabled children were up to seven times more likely to experience sexual abuse than non-disabled children.[1546]

1167. Studies conducted since the 2000s estimate that the risk of child sexual abuse is about three times higher for disabled children than non-disabled children.[1547] A 2000 study by Sullivan and Knutson that used school, foster care, and police data bases together with record reviews to examine the extent of abuse and neglect, reported a prevalence of 31 percent for disabled children and 9 percent for non-disabled children.[1548]

1168. Not only are disabled children and adults more likely to experience abuse, there is evidence to suggest that abuse occurs for longer periods. A 2008 report found that the duration of abuse reported by disabled women ranged from one to 22 years, with women with greater care needs reporting near life-long abuse.[1549] Another earlier report also found that women with physical impairments suffered abuse (sexual, physical, and emotional) for a longer duration than their non-disabled counterparts.[1550]

1169. In 1991, a report showed 162 cases of sexual abuse in the US and found that disabled people with a wide variety of impairments were frequently the victims of sexual abuse as children and / or sexual assault as adults. They found 20 percent of victims reported a single offence, while 20 percent reported two to 10 incidents, and 50 percent disclosed 10 or more incidents of sexual abuse. The remainder (9.4 percent) described abuse as ‘repeated’.[1551] One study based in Hawaii found that abuse and neglect notifications were three-and-a-half times higher for children with a learning difficulty.[1552]

Te roanga o te tūkinotanga i roto i ngā whakaritenga mātauranga

Extent of abuse in education settings

Te whakatau tata o te taupori

Estimated population

1170. In this section, education includes residential special school and regional health schools, non-residential special schools and non-religious boarding schools.

1171. The MartinJenkins report estimates a total of about 102,000 people were in education settings during the Inquiry period. The report further estimates how many people probably experienced abuse in education settings. Their analysis of available data from international studies provided a low estimate of people suspected to have been abused – 18,570 (18 percent) a high estimate – 33,349 (33 percent).

Ngā rangahau, ngā ripoatatanga rānei mō te whānuitanga o te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

Research or reporting on the extent of abuse and neglect

1172. The Ministry of Education Notice to Produce revealed that complaints data, regarding misconduct and abuse in education settings, was not recorded and collated at a national level until 2013, and incidents went unrecorded until 2016.[1553] Complaints of misconduct were, and continue to be, managed by boards of trustees.[1554] Schools are required to act on incidents if they occur, including reporting to the Teaching Council, NZ Police and / or Oranga Tamariki where appropriate.[1555]

1173. The Ministry of Education is also included within the historic abuse claims process, although the scope has limitations. You may be able to lodge a sensitive claim with the Ministry of Education if you were abused (physically, sexually, psychologically), mistreated or neglected when you attended:

- a specialist school before 1989

- a primary school prior to 1989

- any State school that is now closed (including specialist schools and health camp schools).[1556]

1174. The Ministry has acknowledged that allegations made through the claims process are restricted to a limited range of schools, noting that its “body of knowledge will grow” as it researches and assesses further claims.[1557]

1175. The Ministry of Education has received a total of 144 abuse claims for residential special schools since 2010, 43 of which have been resolved (33 including settlement payment).[1558] As of December 2020, the residential special schools with the highest number of claims made were Waimokoia Residential School, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland (46 claims), Campbell Park School, Waitaki, North Otago (31 claims), and McKenzie Residential School, Ōtautahi Christchurch (29 claims).[1559]

1176. Within schools that were specifically intended to meet the learning needs of Deaf children and young people, there was a significant extent of abuse reported to the Inquiry. While the number of Deaf survivors who experienced these settings and engaged with the Inquiry are few, an alarming 75 percent of survivors were physically abused while they were there.[1560] In addition, 50 percent of these survivors were sexually abused while they were at a Deaf school, and 44 percent emotionally abused there.

Ngā purapura ora i kōrero ki te Kōmihana mō te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

Survivors who spoke to the Inquiry about abuse and neglect

1177. The Inquiry heard from more than 150 survivors who experienced abuse and neglect in education settings, although a major difference in approach is that DOT Loves Data analysis also includes faith-based boarding schools whereas MartinJenkins did not include faith-based education in their data.

1178. While general data on the extent of abuse in education settings remains limited, the recently published report into the nature and extent of abuse within Dilworth School indicates that a high prevalence of abuse occurred in some education settings within Aotearoa New Zealand. Of 171 former Dilworth students who spoke to that Inquiry about sexual abuse, 126 reported being sexually abused.[1561]

Te whakataunga mō te whānuitanga o te tūkinotanga me te whakahapa

Conclusion on the extent of abuse and neglect in care

1179. Regardless of the data limitations, and the inability to know the true extent of abuse and neglect in State and faith-based care settings in Aotearoa New Zealand, abuse and neglect occurred across all types of care settings and represents a national shame, undermining any claims that Aotearoa New Zealand has always been a compassionate or egalitarian country.

1180. The persistent underreporting and delayed reporting of this abuse, the persistent societal stigma felt by survivors, as well as how many complaints of abuse were effectively ignored or forgotten, has meant that many survivors have had to suffer the long-term effects of their abuse and neglect with little opportunity to connect with others have shared similar experiences.

Footnotes

[1431] MartinJenkins, Indicative estimates of the size of cohorts and levels of abuse in State and faith-based care – 1950 to 2019 (2020, page 9).

[1432]These numbers represent the number of new admissions to a care setting each year. For example, if a child enters a boarding school for 5 years, they are counted once, in the year they first started that school. There is an estimated overlap across the settings of 21% that has been deducted.

[1433] MartinJenkins, Indicative estimates of the size of cohorts and levels of abuse in State and faith-based care – 1950 to 2019 (2020, pages 6–8). See also: Appendix 2: Description of methodology and data sources, page 68.

[1434] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry, September 2023). Note: that DOT’s text-based analysis of accounts has by necessity used different abuse type categories to the Inquiry, to interpret survivors’ information through quantitative data.

[1435] Transcript of evidence of Chief Executive Geraldine Woods for Whaikaha – Ministry of Disabled People at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 17 August 2022, page 214).

[1436] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 74).

[1437] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, pages 72–74, 109).

[1438] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 43).

[1439] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 45).

[1440] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 52).

[1441] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 47).

[1442] DOT Loves Data. Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 9).

[1443] DOT Loves Data. Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 10).

[1444] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 13).

[1445] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, pages 13–14).

[1446] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity, (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 14).

[1447] DOT Loves Data. Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, pages 16–17).

[1448] DOT Loves Data. Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, pages 24–29).

[1449] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 61).

[1450] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, pages 73–76).

[1451] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 39).

[1452] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 44).

[1453] MartinJenkins, Indicative estimates of the size of cohorts and levels of abuse in State and faith-based care – 1950 to 2019 (2020, page 24).

[1454] Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Final report: Religious institutions, Volume 16, Book 1 (2017, page 79).

[1455] TDB Advisory, Peer review of MartinJenkins report: A report prepared for Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (2020, page 5).

[1456] Oranga Tamariki, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 418 (10 June 2022, page 78, para 8.10).

[1457] Oranga Tamariki, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 418 (10 June 2022, page 78, para 8.10).

[1458] Oranga Tamariki, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 418 (10 June 2022, page 136,para 18.27).

[1459] Witness statement of Gary Hermansson (1 October 2022, para 5.2).

[1460] Witness statement of Gary Hermansson (1 October 2022, para 5.3).

[1461] Independent Children’s Monitor, Experiences of care in Aotearoa: Agency compliance with the National Care Standards and Related Matters Regulations (January 2022, page 32).

[1462] Oral evidence of Nicolette Dickson for Oranga Tamariki at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 24 August 2022, page 834).

[1463] Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, He Purapura Ora, he Māra Tipu: From Redress to Puretumu Torowhānui (2021, pages 257-260).

[1464] Fry, D, Lannen, P, Vanderminden, J, Cameron, A & Casey, T, Child Protection and disability: Ethical, methodological and practical challenges for research (Dunedin Academic Press, 2017).

[1465] MartinJenkins, Indicative estimates of the size of cohorts and levels of abuse in State and faith-based care – 1950 to 2019 (2020, pages 35–36).

[1466] Oral evidence of Chief Executive Chappie Te Kani for Oranga Tamariki at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 24 August 2022, page 807).

[1467] Witness statement of Professor Elizabeth Stanley (11 October 2019, page 2, para 6).

[1468] Transcript of Professor Elizabeth Stanley examined by Ms Spelman at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 4 November 2019, page 4).

[1469] Von Dadelszen, J, Sexual abuse study: an examination of the histories of sexual abuse among girls currently in the care of the Department of Social Welfare (Research Section, Department of Social Welfare, 1987, pages 46–48).

[1470] Ministry of Social Development, Response to the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 14: Quantitative analysis based on information regarding applicants to MSD's historic claims process (2021). See also: Ministry of Social Development, MSD spreadsheet of claimant data and allegations (2020). Note: 208 allegations in total as at 13 October 2020.

[1471] Witness statement of Hurae Wairau (29 March 2022, paras 23–26).

[1472] Ministry of Social Development, MSD spreadsheet of claimant data and allegations (2020).

[1473] Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand, Auckland University Press, 1998).

[1474] Stanley, E, The road to hell: State violence against children in postwar New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 2016).

[1475] Parker, W, Social welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume II: National institutions (Ministry of Social Development, 2006).

[1476] Sutherland, O, Justice and race: Campaigns against racism and abuse in Aotearoa New Zealand (Steele Roberts, 2020).

[1477] Auckland Committee on Racism and Discrimination, Ngā Tamatoa & Arohanui Inc, Child welfare or Child abuse? Compiled by ACORD for the Public inquiry into child welfare homes, 11 June 1978, in association with Nga Tamatoa and Arohanui Inc (ACORD, 1979), in Sutherland, O, Index of the Document Bank for the brief of evidence of Oliver Robert Webber Sutherland, (Wai 2615), document A12(a), (2017, page 142).

[1478] Auckland Committee on Racism and Discrimination., Ngā Tamatoa & Arohanui Inc, Child welfare or Child abuse? Compiled by ACORD for the Public inquiry into child welfare homes, 11 June 1978, in association with Nga Tamatoa and Arohanui Inc (ACORD, 1979), in Sutherland, O, Index of the Document Bank for the brief of evidence of Oliver Robert Webber Sutherland, (Wai 2615), document A12(a), (2017, page 146).

[1479] Confidential Listening and Assistance Service, Some memories never fade: Final Report of The Confidential Listening and Assistance Service (2015, (page 9).

[1480] Confidential Listening and Assistance Service, Some memories never fade: Final Report of The Confidential Listening and Assistance Service (2015, page 27).

[1481] Horwood, J, Department of Social Welfare and related care in the CHDS cohort [Unpublished] (Christchurch Health and Development Study & University of Otago, 2020), in MartinJenkins, Indicative estimates of the size of cohorts and levels of abuse in State and faith-based care: 1950 to 2019 (2020); Savage, C, Moyle, P, Kus-Harbord, L, Ahuriri-Driscoll, A, Hynds, A, Paipa, K, Leonard, G, Maraki, J & Leonard, J, Hāhā-uri, hāhā-tea: Māori Involvement in State care 1950–1999 (Ihi Research, 2021).

[1482] Ministry of Social Development, MSD Master Spreadsheet of Allegations, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce14 (2020)

[1483] Ministry of Social Development, MSD Master Spreadsheet of Allegations, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 14 (2020)

[1484] Ministry of Social Development, MSD spreadsheet of claimant data and allegations (2020).

[1485] Ministry of Social Development, MSD spreadsheet of claimant data and allegations (2020).

[1486] Ministry of Social Development, MSD Master Spreadsheet of Allegations, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce (2020)

[1487] Confidential Listening and Assistance Service, Some memories never fade: Final Report of The Confidential Listening and Assistance Service (2015, page 13).

[1488] Confidential Listening and Assistance Service, Some memories never fade: Final Report of The Confidential Listening and Assistance Service (2015, page 13).

[1489] Oranga Tamariki, Safety of children in care, Annual Report July 2018 to June 2019 (2019, page 6), https://www.orangatamariki.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/About-us/Performance-and-monitoring/safety-of-children-in-care/2018-19/Safety-of-children-in-care-Annual-Report-2018/19.pdf.

[1490] Oranga Tamariki, Safety of children in care, Annual Report July 2018 to June 2019 (2019). https://www.orangatamariki.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/About-us/Performance-and-monitoring/safety-of-children-in-care/2018-19/Safety-of-children-in-care-Annual-Report-2018/19.pdf.

[1491] DOT Loves Data, Data request addition (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, pages 8–9).

[1492] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 4).

[1493] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 23).

[1494] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 29).

[1495] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 42).

[1496] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, pages 14, 18). Note: DOT’s text-based analysis of accounts has by necessity used different abuse type categories to the Inquiry’s Final Report, to interpret survivors’ information through quantitative data.

[1497] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 34).

[1498] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 47).

[1499] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 47).

[1500] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 51).

[1501] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, pages 56–57).

[1502] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, pages 110 – 112).

[1503] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 111)

[1504] Hobbs, GF, Hobbs, CJ & Wynne, JM, “Abuse of children in foster and residential care,” Child Abuse & Neglect, 23(12), (1999, pages 1239–1252.)

[1505] MartinJenkins, Indicative estimates of the size of cohorts and levels of abuse in State and faith-based care – 1950 to 2019 (2020, page 45).

[1506] MartinJenkins, Indicative estimates of the size of cohorts and levels of abuse in State and faith-based care – 1950 to 2019 (2020, page 44).

[1507] TDB Advisory, Peer review of MartinJenkins report: A report prepared for Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (2020. page 4).

[1508] Te Rōpū Tautoko, Information Gathering Project Fact Sheet (1 February 2022) https://www.catholic.org.nz/assets/Uploads/20220201-Tautoko-IGP-Fact-Sheet-1-Feb.pdf

[1509] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 56).

[1510] DOT Loves Data, Data request addition (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 9).

[1511] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, pages 64-65).

[1512] DOT Loves Data, Final report: Quantitative analysis of abuse in care (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, pages 64–65).

[1513] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 4).

[1514] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 4).

[1515] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 4).

[1516] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 4).

[1517] DOT Loves Data, Reporting of abuse types by gender and ethnicity (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, September 2023, page 24).