Tikanga Māori concepts

At a fundamental level, te ao Māori is a relational world, in which what is tika or right depends on the operation of tikanga Māori, the primary informers of behaviour and values that have withstood the test of time. They exist in an interconnected matrix and there are no English word equivalents. Each concept has a depth and richness to it that must be understood in context. The values and principles underlying tikanga remain relatively consistent. However, the way tikanga Māori manifests in particular contexts can vary between different iwi, hapū and whānau.

Some of the core tikanga Māori concepts commonly cited are: whanaungatanga, mana, tapu, utu and kaitiakitanga. In considering tikanga Māori and the rich array of mātauranga Māori concepts that can apply to addressing abuse in care, we have been guided by our pou tikanga and have drawn on both the core well-known principles as well as principles specifically framed within the context of abuse in care.

The whakataukī, “he purapura ora, he māra tipu” has guided how we think about survivors, who we sometimes refer to in this report as “purapura ora”. Purapura means seed and ora means to recover, revive or be alive. The term purapura ora was traditionally used to refer to surviving children whose parents were killed. It signified that despite suffering a traumatic event while young (where they lost a part of themselves that they will never get back) they still remain. He māra tipu refers to a garden of growth. This part of the whakataukī talks about the aspiration of all people to be able to be in a nurturing, safe place and community, where no person is excluded for any reason including disability, whakapapa and family circumstance. This is closely connected with “he mana tō tēnā, tō tēnā – ahakoa ko wai” – a phrase that means each and every person has their own mana and associated rights, no matter who they are.

We have drawn on the whakataukī “he purapura ora, he mara tipu” to refer to the life essence and the ability and potential for survivors to heal and regenerate in spite of the abuse, harm and trauma that they have experienced. Like a seed trampled in a garden, in spite of the damage inflicted, survivors of abuse and neglect in care have infinite potential to still grow or regenerate. A similar idea is captured in the pēpeha “he rātā te rākau i takahia e te moa” or “the rata that was trampled by the moa”. When a rata tree is stood on by the moa as a seedling it may grow up crooked or affected in some way by being trampled on. Embedded in this saying are ideas of accountability and permanent damage as well as resilience, adaptation, growth and potential.

Tūkino is another central concept that has informed how we think about abuse, harm and trauma. The concept of tūkino reflects ill-treatment through violence, abuse, maltreatment, mistreatment, torture and rape. The term tūkino expresses the nature and extent of the abuse, harm and trauma that has been inflicted and suffered and its severity but also acknowledges there is hope of restoration and growth. It implies a transgression that is unjust, unfair, violent, destructive, cruel and abusive. Inherent in tūkino is an acknowledgement that pain, trauma, and grief has been inflicted. We considered using the term hara to reflect abuse, harm and trauma. Hara indicates a violation of tikanga and a transgression or wrong. However, this concept was not considered strong enough and it was not quite sufficient to capture the impact and trauma that abuse has on those who are subject to it. Tūkino was seen to be more appropriate as it carries with it implication of significant distress and a negative impact on the survivor.

When tūkino has occurred, mana is impacted. Words that have been used to convey mana include power, presence, authority, prestige, reputation, influence and control. Everyone is born with and possesses mana, reflecting their actual or potential place in and contribution to their world. The mana of children in traditional Māori society, and the great care and affection accorded most children means that any action that harms a child or fails to respect the child’s mana is significant. Mana has collective and individual dimensions that affect each other. We use the concept of te mana tāngata to talk about the restoration and respect for the inherent power, dignity and standing of people affected by tūkino.

Another tikanga Māori concept important to this kaupapa is utu. Utu is the imperative to set right any tūkino. Utu is the cost that must be suffered as a result of the wrong and the process of restoring the mana and mauri of those who are aggrieved through action that provides recompense, or otherwise reciprocates or balances the harm. Utua kia ea is a process that must be undertaken to account for tūkino and restore mana to achieve a state of restoration and balance. What is required to achieve utua kia ea will differ for each survivor. For some, recognition and an apology will be central but for others this may have very little meaning. Pathways of utua kia ea should include scope for survivors, both as individuals and collectively, to chart their own unique course.

The concept of puretumu includes to seek redress, compensation or obtain satisfaction. It is underpinned by seeking justice and the restoration of mana and provision of compensation to the person and their whānau. The concept of ‘puretumu torowhānui’, or holistic redress, in this context covers a wide range of matters that taken together might be done to put right the tūkino that has been experienced.

The concept of manaaki speaks to the need to treat others with humanity, compassion, fairness, respect and generosity, and the need for responsible caring that upholds the mana of those involved. Abuse in care can impact all parts of a person’s wellbeing. To manaaki a person to grow and achieve utua kia ea may require assistance with multiple dimensions of oranga. Māori models of wellbeing are discussed further below but generally include physical, spiritual, mental, cultural, social, economic and whānau wellbeing.

The tikanga Māori concept of whakaahuru provides for an individual to receive warmth, be cherished and receive comfort. We have drawn on this concept as it provides for the safeguarding and protection of those who have been, or are being, abused in care.

Finally, whanaungatanga is the essential principle through which every element in creation is related, tracing common descent down lines of whakapapa from a single sacred source. In a world where everything is seen through a lens of kinship, the importance of tamariki and mokopuna cannot be overstated. In te ao Māori, all people, all ancestors, and every element of nature are bound together in a web of mutual obligation; each possesses mauri or life force which must be sustained; and all relationships, human or otherwise, must be kept in balance. In this context, the connections that exist between people and the concept of whanaungatanga means that the impact of abuse in care must be looked at beyond solely the individual that has been impacted. The impact can be intergenerational and go beyond the individual and affect whānau, hapū, iwi and hāpori, or communities. Further, if an individual is seen as belonging to a matrix of kinship groups, the inherent harm of removing a child from their whānau becomes evident. This is why from a te ao Māori perspective, removal of children can itself be an act of tūkino – both towards the child and their whānau, hapū and iwi. Viewed through a whanaungatanga lens, puretumu should facilitate individual and collective wellbeing and mana, connection and reconnection to whakapapa, and cultural restoration.

Māori models of wellbeing – Te Whare Tapa Whā

In recent decades, several frameworks have been developed to describe Māori views of hauora, or health, and oranga, and in particular the spiritual, communal, and holistic ways in which wellbeing is understood. These frameworks have been described as being:

“... constructed from land, language and whānau; from marae and hapū; from Rangi and Papa; from the ashes of colonisation; from adequate opportunity for cultural expression; and from being able to participate fully within society.”

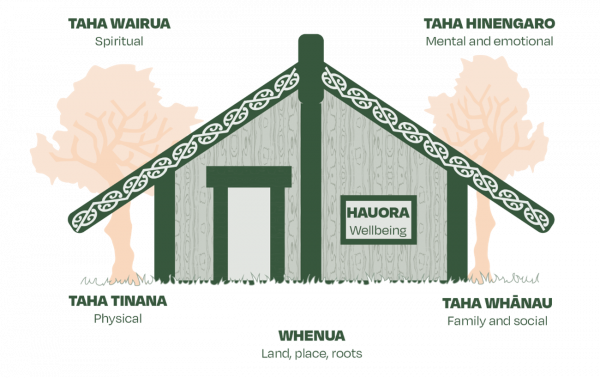

One of the earlier Māori health and wellbeing models, Te Whare Tapa Whā, developed by Ahorangi Tā Mason Durie, is a useful model that is grounded in the tikanga Māori concepts outlined above. We recognise there are other later models; however, we focus on Te Whare Tapa Whā because it is a model many of our survivors are familiar with, and a model some Māori survivors have discussed with us.

In recognising that Māori health was traditionally defined by elders at the marae, the model drew on four basic dimensions of life that are referred to on the marae, ‘te taha wairua’ (spiritual health), ‘te taha hinengaro’ (mental and emotional wellbeing), ‘te taha tinana’ (physical health), and ‘te taha whānau’ (family health). This whare sits on top of the whenua (land), which forms the foundation for the other four dimensions.

Te Whare Tapa Whā uses these dimensions to conceptualise Māori health and wellbeing as four walls of a wharenui.

Diagram One: Te Whare Tapa Whā

Within this framework, taha wairua includes having a sense of meaning and purpose as well as a sense of connectedness to self, whānau, and community. It can also include connectedness to nature, to whenua, and the sacred (including, but not specific to, religious beliefs and practices).

Taha wairua also accounts for the presence of mana, a state not derived from personal strengths or pursuit, but “conferred by the gods, a state of spiritual authority and power, denoting a high level of health without an egocentric core”. To possess mana is to know health.

Taha hinengaro encompasses the nature of one’s thoughts and feelings, and how emotions are expressed. An integral component of this is also how a person views themself. In te ao Māori, thoughts and feelings are seen as fundamental to health, and healthy thinking reflects fundamental values including the wellbeing of the community. To place personal ambition above communal good is to be unhealthy, even if the body is fit.

Taha tinana is about one’s physical health, including physical activity, how food is prepared and consumed, and tikanga around the body, and especially about bodily functions. These tikanga were routinely ignored in hospitals and other State institutions, creating an environment that caused distress and was unsafe for Māori.

Taha whānau refers to the health of relationships and the wider kinship system, including not only immediate family but all kin and the wider community. Taha whānau recognises the importance of whānau and their wellbeing, and acknowledges whānau as an essential support system, and as a source of belonging and identity.

The model emphasises balance and interconnection between all the dimensions. Should the wairua, hinengaro, tinana, whānau or whenua be missing, neglected, or damaged in some way, the person and their collective or group may become unbalanced and unwell.

Te Whare Tapa Whā provides a framework through which puretumu torowhānui for purapura ora, or survivors, can be viewed holistically, as a process that restores, reconnects, empowers, and builds mana.

There are also other useful models of Māori wellbeing. These include:

- the Pā Harakeke model, based on the structure of a flax plantation

- Te Wheke model, based on the tentacles of the octopus

- Te Pae Māhutonga model based on the Southern Cross constellation

- the Meihana model developed for use within the mental health system.

These various models demonstrate that a te ao Māori approach to puretumu torowhānui should be multi-faceted and holistic, and centred on supporting and improving the capability of the individuals and the collective. It should aim to heal and restore balance, by restoring the mana and mauri of survivors and their whānau, hapū and iwi, including through connecting and reconnecting with whakapapa and mātauranga Māori.