Pacific peoples’ concepts of harm and restoration

As noted, in Aotearoa New Zealand, the term ‘Pacific’ encompasses more than twenty Pacific nations with unique languages, customs, beliefs, cultural values and traditions. Pacific peoples who have migrated to or were born in Aotearoa New Zealand have kept a particular set of cultural and spiritual values that have been passed down the generations by ancestors, through to families and communities. These values are represented in a Pacific worldview that is holistic, collective and relational.

We heard from a number of Pacific survivors and experts at our public hearing on Pacific people’s experiences of abuse in care in July 2021. In particular, a talanoa panel of Pacific experts discussed redress. The experts spoke to the importance of understanding key Pacific concepts, in particular the vā, in order to frame what a new redress approach for Pacific survivors of abuse in care might look like.

The vā – relationality

The concept of vā is fundamental to understanding the Pacific worldview. Sister Vitolia Mo’a writes that “relationship and mutuality – the vā – signifies the vā-tapu and vā-tapuia, or the sacred relational space among inter-connected entities. Inherent in the concept of vā is the recognition of both distinctiveness and relationality.” Samoan people’s understanding of the workings of their social, cultural, economic, and religious systems is rooted in vā and this recognition of interconnectedness. Faasinomaga or identity “situates the Samoan person within the interconnected and inter-related levels of vā, in that which is understood as a cosmic cyclic form of existence”.

Albert Wendt defined the vā as “the space between, the betweenness, not empty space, not space that separates but space that relates, that holds separate entities and things together in the Unity-that-is-All, the space that is context, giving meaning to things. The meanings change as the relationships / the contexts change.”

Teu le vā and tauhi vā is the tending to and nurturing of interconnected relationships or vā between people and places.

Conceptions of vā from across the Pacific are not identical. While it would be a presumption to consider vā as a single phenomenon across Pacific cultures, there are reflections of vā in cultural practices of Pacific people who are not Samoan. Differences in detail aside, migration has meant that the essential aspects of vā are shared and recognisable across various Pacific cultures.

When a Pacific person is abused in care, that is a violation of that relationship and a damage to the vā. This is sometimes referred to as soli le vā. Another way of looking at it is that when there is abuse, harm and trauma the vā no longer exists.

Violation of the vā, or the loss of the vā, is evident in Pacific survivors’ experiences of being abused and neglected in care by people who were supposed to look after them, as well as being disconnected from their families, communities, cultures and languages. To soli le vā of a Pacific person would be to violate that person, their families and their genealogies. In this way, their families are also victims of the abuse.

Healing / restoring the vā

Pacific cultures have various customs and practices for healing the vā and restoring this balance, including ifoga (Samoa), ho’oponopono (Hawai’i), isorosoro (Fiji), and fakalelei (Tonga) to name a few.

Ifoga is a ceremonial public apology in which an offender and their wider family make a request for forgiveness to those harmed. It can be adopted as a form of restorative justice whereby the whole family and village takes collective responsibility for the offender’s actions and seeks to right the wrong directly with the victim and the victim’s family. One survivor explained it as “a display of significant respect, humility, and a sincere request for forgiveness”.

Fakalelei is similar to ifoga but less formal and is adaptable depending on the time, context and other circumstances. The literal translation for ‘fakalelei’ means ‘to mend, repair, improve, to reconcile’ and is practiced in Tongan communities with the same principles of humility, respect, apology and seeking forgiveness.

Ho’oponopono literally translates as “to make right”. Expert Dr Michael Ligaliga distinguished between setting something right and making something right, suggesting that “making” something right promotes ownership of the process.

Careful consideration of the values and principles that underpin these cultural practices is essential in considering a new redress process that seeks to heal and restore the vā.

The multicultural nature of Pacific communities in Aotearoa New Zealand means that these cultural practices need to be adapted and reappropriated. Care must be taken in determining which mechanisms to use, and/or whether to use them at all.

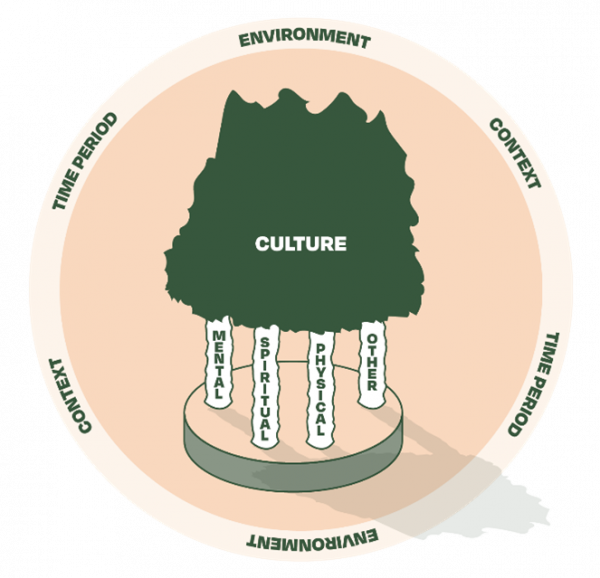

Diagram Two: Fonofale Model

“E sui faiga ae tumau fa’avae”

Our practices may change but the values and foundations of the cultural traditions remain.

The Fonofale model and “cultural humility”

Several cultural frameworks have been developed to describe Pacific views on different areas including health, wellbeing, education and family violence. Earlier Pacific models of health and wellbeing (especially the Fonofale model) have been built into the frameworks of various Pacific and mainstream health services.

It is not possible to have a one-size-fits-all redress process for Pacific survivors, because of the changing population, demographics, and beliefs and value systems of the children of the Pacific diaspora in Aotearoa New Zealand. However, Pacific experts spoke to us about the Fonofale model, as well as concepts of “cultural humility” and restorative justice as central features of any new redress process for Pacific survivors of abuse in care.

The Fonofale model adopts the metaphor of a Samoan fale, or house, and includes elements from many Pacific nations including the Cook Islands, Niue, Fiji, Tokelau and Tonga.

The foundation of the fale represents family, providing support for the entire fale structure. Family is generally seen as the foundation for all Pacific Island cultures. The roof represents cultural values and beliefs and acts as the shelter of the family for life.

Between the roof and the foundation are four pou. Each pou represents a fundamental element of a person’s wellbeing:

- spiritual – a person’s spiritual sense of wellbeing, which stems from a belief system that includes either Christianity or traditional spirituality relating to nature, spirits, language, beliefs, ancestors and history, or a combination of both

- physical – a person’s biological or physical wellbeing, the anatomy and physiology of the body as well as physical or organic and inorganic substances such as food, water, air and medications that can have either positive or negative impacts on the physical wellbeing

- mental – the wellbeing or the health of the mind which involves thinking and emotions as well as the behaviours expressed

- other – other variables that can directly or indirectly affect health such as gender, sexuality/sexual orientation, age, and socio-economic status.

The fale sits inside a cocoon that contains three further elements that influence a person’s wellbeing:

- the environment – the unique relationships Pacific people have to their physical environment, which may be a rural or an urban setting

- time – the actual or specific time in history

- context – the where/how/what and the meaning it has for that particular person or people, including whether they were raised in Pacific Islands or Aotearoa

New Zealand, their country of residence, and the legal, political and

socio-economic context.

The Fonofale model reminds us that it is important to consider context, environment and time when trying to understand the wellbeing of a person. For example, a Pacific survivor of abuse that occurred in 1950 may not find a 1950 resolution useful when seeking redress in the present. Addressing the survivor and their family’s current needs is what will make the difference.

“Cultural humility” is another key concept relevant to how we approach redress. Pacific criminologist Dr Tamasailau Suaali’i-Sauni highlighted that all of us – as the society of Aotearoa New Zealand, and Pacific peoples in Aotearoa – need to develop cultural agility and humility to enable us to navigate our many challenges.

Dr Jean Mitaera, described “cultural humility” as “the ability to be able to stand and have a consciousness of the other.” She told us that in the context of abuse in care, a cultural humility approach invites the State and churches to stand and have regard for Pacific peoples in care, in coming up with a resolution that is transactional, transformative, but importantly, has regard for the differences and needs of all.

Cultural humility focuses on both individual and organisational accountability, lifelong learning and critical reflection, and reducing power imbalances. It makes clear the interaction between the institution and the individual and the presence of systemic power imbalances.

These models and frameworks can work together in a broader framework for redress, provided they are put in place in a way that is culturally inclusive of the diverse Pacific cultures and suitable to the particular survivors’ needs. Holistic Pacific models of care that include Pacific values must be used to ensure Pacific mental health and wellbeing.