Chapter Five: Complaints and Accountability Upoko Tuarima: Ngā nawe me ngā Kawenga

Whakatakinga

Introduction

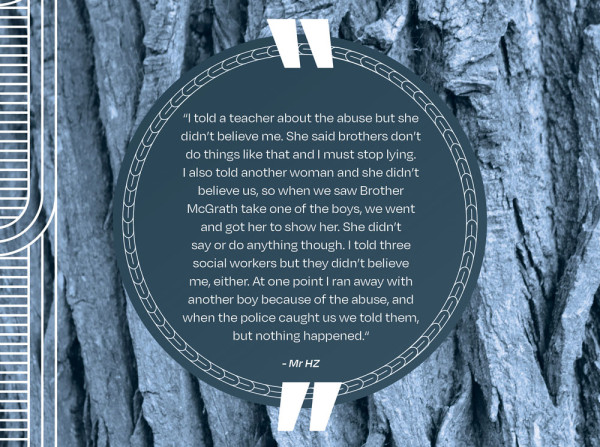

1. Despite few visits by social workers to Marylands and Hebron Trust, some boys did manage to tell social workers about the abuse inflicted on them. In most cases, however, social workers did not believe them. Some social workers made a record of the allegations, but as far as we can tell, the Department of Social Welfare did nothing more than file the information away.

2. Children also managed to tell teachers and the police, but no steps were taken to intervene and in most cases the boys were not believed.

3. The Inquiry looked into what happened with the many disclosures and complaints raised, the steps taken by survivors, their whānau and support networks to continue to raise complaints and what the State and Order did or did not do. We also inquired into what redress some survivors received. Finally, we have formed a view on the human rights obligations and te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations owed by the Crown, the church and the Order to those in care at Marylands and Hebron Trust.

Te whakautu a te Kāwanatanga ki ngā nawe mō ngā tūkinotanga Responses by the State to complaints of abuse

4. According to police records, a witness made a disclosure in April 1992 to the Department of Social Welfare regarding Brother McGrath sexually abusing a boy, yet he still spent time alone with him after the complaint was made.[428] The survivor subsequently withdrew his complaint.

5. It is unclear when information about this survivor’s abuse first became known to police, but it appears to have been around the time the complaint was first raised (and withdrawn) as the police officer running the investigation recalls this happening.[429]

6. In addition, in June 1992 a probation officer arranged a visit to Hebron Trust to discuss the allegations.[430] Nothing further was done at that time and Brother McGrath continued to work with vulnerable young people. In October 1992, a Hebron Trust youth worker provided a formal statement to police about this abuse.[431]

7. A former Marylands student disclosed to his social worker in 1992 that he had been abused by Brother McGrath and that there was a possibility other brothers were abusing as well.[432] He also reported the abuse to police.[433] He told his social worker that, while he can’t remember the names of all the other boys who were abused, there were at least 40.[434] He said that if he had a list of the boys who were attending the school at the time, he would have been able to pick out their names.[435]

8. Another of the first survivors to come forward, Justin Taia, was abused at Hebron Trust between 1989 and 1992.[436] The abuse was severe. Justin was addicted to substances, and Brother McGrath provided him with alcohol and pills, including Rivotril, as a way of maintaining power over him.[437]

9. Justin ended up living in a small cottage owned by the Order and Brother McGrath ‘paraded’ him around before other brothers and staff at community meals.[438] Brother McGrath acted as Justin’s representative and advocate, writing letters of support to the court and being the contact person for social workers.[439] He also supervised Justin’s community work at Hebron Trust and attended Family Group Conferences with him.[440]

10. Despite the extremely high level of control that Brother McGrath exercised over Justin’s life, in around May 1992, Justin stood up to Brother McGrath. He threw a glass at Brother McGrath’s head in front of the other street kids, telling him to leave him alone and never touch him again.[441] Justin formally reported the abuse in around 1993.[442]

11. We heard that on several occasions local police found and returned boys who had run away from Marylands. Police showed little interest in finding out why the boys were running away, or what they were running from, even when the boys said there was abuse occurring. Detective Superintendent Peter Read told us NZ Police accepted they had missed an opportunity in the 1970s to identify Marylands as a possible location of child abuse.[443] When the boys reported abuse to police at that time, an investigation should have been commenced but was not.

12. Police also did not keep adequate records about incidents of boys who ran away from Marylands. Police could not find any pre-2002 records of students absconding from Marylands and being returned by police, or reporting abuse to them.

13. On several occasions, police received information about abuse at Marylands from sources other than students. For example, in May 1991, police received an anonymous phone call advising that Brother McGrath at Hebron Trust was “suspected of interfering sexually with little boys”.[444] Police’s Child Abuse Unit was informed but decided there was no need to take any action. It also decided there was insufficient information to enter the allegation in their national computer system.[445] Instead, officers simply filed a report and the file was archived. This meant that it was harder to ensure any pattern of allegations about Brother McGrath showed up over time.

Te whakautu a te Rangapū me te Hāhi Katorika ki ngā nawe mō ngā tūkinotanga me te panoni wāhi noho

Responses by the Catholic Church and the Order to complaints of abuse, including geographic cure

14. The Order often did not record complaints of abuse. At times, the attitude within the Order was that the offending was a sin (failing to keep the vow of chastity) rather than a crime.[446] The victims were not given much consideration,[447] so keeping detailed records was not a high priority.

15. In a police interview, former Provincial Brother O’Donnell said that no allegations of sexual misconduct involving brothers were ever documented.[448] Reports of abuse were dealt with verbally and without documentation.[449] This approach was taken to avoid compromising the good name of the alleged abusive brother.[450] A documented record of abuse could jeopardise the brother’s future life within the Order.[451]

16. In the 1970s, Mr HZ reported to a teacher and Brother Garchow, that he was abused by Brother Moloney and Brother McGrath.[452] This report was not recorded. This information is not included in the Order’s raw data or the summary of what it knew and when.[453]

17. Brother O’Donnell described the former response of the Order as “institutional protectiveness”.[454] Another former brother confirms that there was a general sense of denial.[455] According to Dr Michelle Mulvihill, these attitudes remain the same today:

“Systemic abuse happens when good people place their trust in organisations and believe and hope that they stand for good, not for evil. Systemic abuse continues to take place when it is in the very DNA of the culture of any organisation. St John of God brothers demonstrate that they have caught a kind of organisational amnesia. They seem to have found a collective mute button, worldwide. Such an abusive culture installs a filter on the lens they use to see victims as they truly are. They install a damper, some blinders, some organisational ear plugs and then take a nap. The St John of God brothers as a worldwide organisation seem to have a need to erase these stories in each and every country they operate, misplace these tapes, zoom out, and slowly dissolve to black.” [456]

Te panoni wāhi noho – te whakanekeneke i ngā parata kaihara mai i tētehi whakahaere ki tētehi, whai muri i ngā nawe mō ngā mahi tūkino

Geographical cure – moving offending brothers from one institution to the next after complaints of abuse

18. Even if boys reported abuse, often nothing was done about it.[457] The Order’s leadership were aware of allegations of abuse in the 1960s, 70s and 80s,[458] but, in some cases, simply moved the offending brothers from one institution to another.

19. The practice of responding to allegations or suspicions of abuse by transferring the alleged abuser is known as the ‘geographic cure’. This movement of alleged perpetrators was how the Order dealt with the earliest allegations of sexual abuse.

For example, in Australia, allegations relating to a 1962 disclosure in respect of the Order, came to light when Brother O’Donnell made a statement to police in 2003:[459]

› Brother O’Donnell states that while he was Superior at Cheltenham, Victoria, between 1962 and 1967, he received a complaint of sexual abuse in respect of a Brother Bede who was working within the Order, in Australia.

› Brother O’Donnell states that as a result of the complaint, Brother Bede was transferred out of Cheltenham.

20. Brother Graham told the Victorian Parliamentary Inquiry that the earliest report of sexual abuse involving brothers in Australia was 1992. We note that the disclosure to Brother O’Donnell was 30 years before that date.[460]

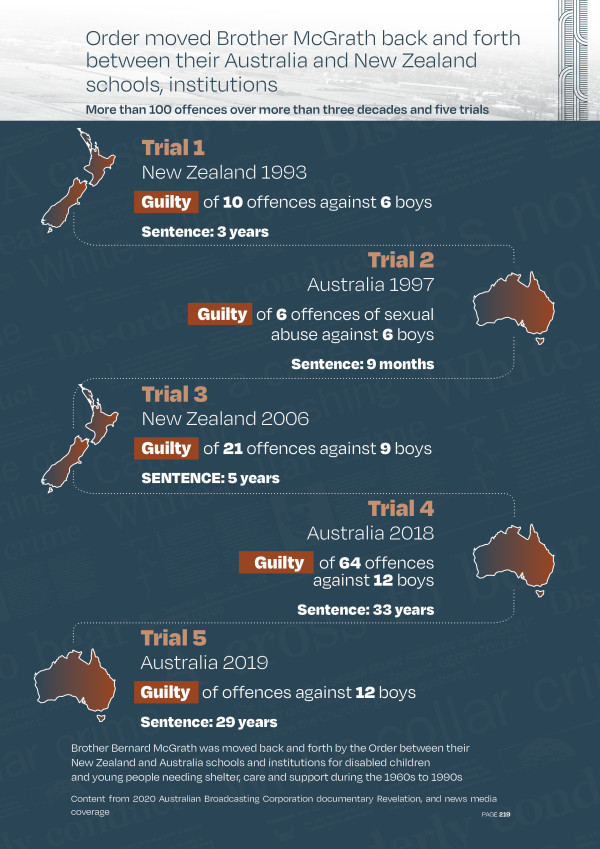

21. In 1977, two anonymous letters to Brother O’Donnell reported abuse in Christchurch, by Brother McGrath and Brother Moloney.[461] On 3 September 1977, Brother McGrath received a phone call from Brother O’Donnell telling him he was being transferred to Australia. It is likely that the transfer occurred not long after Brother O’Donnell received one or both of the letters.

22. The Order had a very controlled and powerful hierarchy.[462] At any stage, the brothers could be relocated at short notice to work in different institutions in Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia or Papua New Guinea. The practice of regularly relocating brothers, whether because of abuse or for other reasons, contributed to much higher levels of offending than would otherwise have been the case. It also means that it is difficult for any single country to get a complete picture of the harm inflicted by this Order in the Oceania Province, or more widely. Brother O’Donnell said that if an allegation was made against a brother, and he acknowledged that there was truth in the allegation, the brother would be counselled to seek forgiveness from God, to deepen his life of prayer and to live a more ascetical and disciplined life.[463] If he were transferred elsewhere, it would be to give him a chance to change his behaviour.[464]

Ngā hāmene taihara ki ngā parata

Criminal prosecutions against brothers

Parata McGrath (ngā hāmene i te tau 1993 me te tau 2006) Parata Moloney (hāmene i te tau 2008)

Brother McGrath (1993 and 2006 convictions) and Brother Moloney (2008 conviction)

23. There were two police investigations into Marylands and Hebron Trust, which took place almost 10 years apart. The first investigation in 1993 related to abuse by Brother McGrath at both Marylands and Hebron Trust. The second investigation related to abuse by many brothers, including Brother McGrath, at Marylands.

24. The Order spent enormous sums defending the criminal charges brought against its members, including fighting applications to extradite several brothers to Aotearoa New Zealand to face trial.

Uiuinga Parata McGrath

Brother McGrath investigation

25. The 1993 investigation started because of whistleblowing by survivors and others.[465]

26. The investigation was managed by Sergeant Lew Corbett although he didn’t have any specialised training to take on that work.[466] He believes that the investigation should have been dealt with by a detective from the Criminal Investigation Branch, not a sergeant.[467]

27. Sergeant Corbett was the only person assigned to the investigation, so it moved slowly.[468]

28. Despite these difficulties, and the lack of resourcing, Sergeant Corbett says that attitudes toward reports of male sexual abuse had been even worse in the past:

“I have witnessed many changes in policing over my years serving in New Zealand. There were very few male victims of sexual offences up until the 1990s. Back in the 1960s, you would have heard comments like ‘just harden up’ or similar, if a male wanted to complain.”[469]

29. Sergeant Corbett says that he did his job properly. However, he is not confident that police, at that time, would have appropriately investigated complaints about the brothers.[470]

30. During the investigation, the Order sent Brother McGrath to Australia. Sergeant Corbett said:

“This was rather annoying because I believed it was a direct result of both McGrath and the Order of St John of God learning of my investigation. I was speaking to numerous people in connection with the Hebron Trust at the time, so there was no way that they were unaware.”[471]

31. He also found it difficult to get information from both the State and the Catholic Church:

“…I got the run-around from the church when I attempted to get lists of attendees at Marylands and the Hebron Trust. Most of the time I hit a stone wall. I struggled getting records from Marylands School and was told by the diocese that the records were either lost or unable to be located. I also struggled to get any useful records from the education department.”[472]

32. Police received eight reports of abuse against Brother McGrath. Four of those complaints related to abuse at Marylands and four at Hebron Trust. Charges were laid in relation to seven of these eight reports.[473] One Marylands’ complainant, Mr HZ, got halfway through his formal statement with police and did not continue.[474] The offending at Marylands occurred in the mid-1970s, and the offending at Hebron Trust was more recent.

33. Sergeant Corbett spoke to the Provincial of the Order about contacting Brother McGrath, but the Order was reluctant to bring Brother McGrath back to Aotearoa New Zealand.[475] To make progress, Sergeant Corbett contacted the Order’s Aotearoa New Zealand lawyer, Lee Robinson. Sergeant Corbett admits that he “did not do everything by the book” in his dealings with Mr Robinson.[476] He gave Mr Robinson a summary of the allegations against Brother McGrath, and it was agreed that Brother McGrath would not be interviewed when he returned to Aotearoa New Zealand but would instead plead guilty to the police summary of facts. Sergeant Corbett says that he “disagreed with this”, but that it was “the best option under the circumstances”.[477]

34. Brother McGrath did plead guilty and on 23 December 1993 he was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment in relation to 10 charges of indecencies committed upon victims between the ages of eight and 16 years.[478] He was granted parole in 1995.[479]

2002/2003 ketuketutanga a ngā pirihimana e pā ana ki ngā tūkinotanga i te Kura o Marylands

2002/2003 police investigation into abuse at Marylands School

35. In 2002 and 2003, police undertook a more detailed investigation into abuse at Marylands. It was given the code name ‘Operation Authority’. Detective Superintendent Peter Read (then Detective Inspector) oversaw child sexual violence investigations in Christchurch in the early 2000s. He oversaw Operation Authority and appointed the police investigation team. Detective Superintendent Read gave evidence at the Inquiry’s February 2022 hearing into the Order.

36. Operation Authority began after a television documentary and media coverage in 2002 about abuse at Marylands, which resulted in police receiving complaints from throughout Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia.[480] In addition, Brother Peter Burke and Dr Michelle Mulvihill encouraged survivors who approached the Order to speak to police. Many did so.

37. Operation Authority once again involved allegations against Brother McGrath who, by that stage, had also been sentenced to a nine-month term of imprisonment in Australia for sexual offending there.[481] It also related to allegations of abuse committed by many other members or former members of the Order.[482] The allegations were of sexual indecencies, sodomy and physical abuse.[483]

38. Operation Authority gathered a lot more momentum than the first investigation. Even so, police did not proactively seek out complainants.

![A picture of a quote that says “I made statements to Christchurch police in relation to abuse I suffered ... It was a stressful time having to relive the memories of the physical and sexual abuse I had endured … In making a complaint to the police it was my intention to have those responsible exposed and for them to be held accountable in a court of law. I was prepared to give evidence at a trial for Brother [IU], but this never occurred as the trial was cancelled at a late stage. I felt that he and the others, who had since passed away, had gotten away with abusing kids as we never had the opportunity to tell the truth in court.” - Mr IR](/assets/page-banners/Stolen-Lives/IR2__ResizedImageWzYwMCw0NjNd.jpg)

39. The Order itself received more than 100 allegations of sexual abuse in 2002 and 2003.[484] Police did not contact all these people, even though all the names were provided to them, as the Order had advised them to contact police if they wanted to pursue a criminal complaint.[485] During the investigation, only 56 people reported abuse at Marylands to police, including two of the complainants who had already disclosed abuse by McGrath in 1993.[486] Some people who contacted police had not approached the Order.

40. Police said that the reasons why many former pupils didn’t make complaints to them included: “intellectual ability to give evidence in court hearings, previous criminal offending and lack of respect/trust in police, fear of the judicial system, and in many cases embarrassment and reluctance to disclose the offending and effects of the offending in court.”[487]

41. Unlike the approach that would likely be taken now in a mass allegation situation, police did not carry out scoping interviews of all the people who attended Marylands or Hebron Trust to find out whether abuse had occurred.[488] NZ Police say that in deciding not to approach all 537 former pupils of Marylands, consideration was given to the extensive media reports asking victims to contact police, the number of victims who had come forward already, and the interviews with complainants who had named other students as possible victims or witnesses to abuse. Those people were then contacted by investigators and asked if they had been abused too.[489] Detective Superintendent Read said that investigating officers were conscious that being contacted by police can be difficult for victims,[490] but also acknowledged that an approach to all former pupils “…would have necessitated a far larger response”, indicating resourcing was a factor.[491]

42. The Operation Authority police investigation team was small, involving Detective Superintendent Read, a detective sergeant and three detectives who were selected for their “particular skill, sensitivity, and experience in handling this type of investigation”.[492] However, at the time police had no specific training in dealing with at-risk adults, disabled people[493] and Māori or Pacific complainants.

43. Police worked with others to try and support the complainants, including Ken Clearwater, an advocate with the Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse Trust in Christchurch. The Trust provided specialised support to the complainants throughout the investigation and court processes, as did other counsellors and support people.[494] Police spoke to the whānau of complainants and to current caregivers to assess needs and the best ways of interviewing and providing support.[495]

44. Of the 58 complainants[496] who made statements to police of sexual abuse by brothers at Marylands, approximately 20 percent alleged a single incident of abuse. Most complaints described multiple occasions of abuse, and 18 complainants disclosed abuse by more than one perpetrator. Of those, five reported three or more perpetrators.[497] Three complainants described more than one perpetrator abusing them at the same time and a “handful” described another student being present.[498]

45. The alleged abuse included the full range of sexual offending from indecent touching to anal sexual violation. Many complainants described coercion and pressure to comply including rewards and threats, or actual physical violence during the sexual abuse. Complainants described being physically injured by the abuse, including rectal bleeding.[499]

46. The complainants were aged between six and 16 years old at the time of the abuse.[500] The delay between the abuse occurring as a child at Marylands and reporting to police as an adult ranged between approximately 17 to 45 years.[501]

47. Police only recorded ethnicity for 47 of the 58 complainants,[502] of whom 43 were recorded as European/Pākehā and four as Māori. Detective Superintendent Read described data on disability as ‘somewhat unclear’: “Approximately 21 of the 58 complainants indicate that they had a disability in their formal statements. The disabilities referred to include autism, dyslexia, intellectual disabilities, and learning disabilities. A number of other formal statements indicate the complainant was sent to Marylands due to behavioural issues and/or being a ‘slow learner’.”[503]

48. Police attempted to obtain other evidence to corroborate the complainants’ allegations. They gathered historical documents from Brother Peter Burke and from complainants and their families, including photographs, Department of Education records and school records. Detectives interviewed surviving staff members and other potential witnesses named in the complainants’ statements.[504]

49. In June 2003, four detectives travelled to Australia where they interviewed complainants and members of the Order as witnesses, and tried to interview four of the brothers named as perpetrators. Of those, Brothers Lebler and Moloney declined to be interviewed.[505]

50. Not all survivors were happy with the way police dealt with them.[506] Detective Superintendent Read acknowledged at the Inquiry’s public hearing that the investigation process requiring re-interviewing was traumatising for some complainants.[507]

51. But some spoke highly of the officers who ran the investigation. Ken Clearwater, an advocate who worked with many of the survivors, said:

“The police that were involved went above and beyond. They were so easy to work with. I admired the work they did at the time especially with the lack of resources, which was appalling. We are talking about people who had spent their lives fighting police officers being able to work with them through this process due to the empathy that the cops showed. Without that empathy I doubt things would have gone far. That needs to be acknowledged.”[508]

[428] Witness statement of Peter Read, statement on post-hearing maters for the Marylands School public hearing, WITN0838004 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 7 April 2021), para 3.1(a).

[429] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146002, para 4.5. See also: Report to Minister for Social Welfare from NZ Community funding agency, regarding Bernard McGrath and accountability for Hebron Trust, ORT0006888 (undated) paras 4.1–4.2. Police made approaches to Hebron in August 1992, but did not take formal action.

[430] Witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838004, para 3.1(d)

[431] Witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838004, para 3.1(f).

[432] Report to Minister for Social Welfare from NZ Community funding agency, ORT0006888.

[433] Report to Minister for Social Welfare from NZ Community funding agency, ORT0006888 paras 3.2, 4.2.

[434] Report to Minister for Social Welfare from NZ Community funding agency, ORT0006888.

[435] Report to Minister for Social Welfare from NZ Community funding agency, ORT0006888.

[436] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 354.

[437] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 357.

[438] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, paras 358, 360.

[439] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 359.

[440] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 359.

[441] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 362.

[442] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 363.

[443] Transcript of evidence of Peter Read, TRN0000416, p 51, pp 517.

[444] NZ Police report forms by Detective Sergeant W R Mitchell, regarding Brother Bernard McGrath, NZP0048198 (NZ Police, 1991), p 5.

[445] NZ Police report forms by Detective Sergeant W R Mitchell, NZP0048198, p 4.

[446] Statement from Brian O’Donnell to NZ Police regarding his life in the St John of God Order and knowledge of historical sexual abuse, NZP0012941 (NZ Police, 24 July 2003), p 5.

[447] Statement from Brian O’Donnell, NZP0012941, p 6.

[448] Statement from Brian O’Donnell, NZP0012941, p 5.

[449] Statement from Brian O’Donnell, NZP0012941, p 5.

[450] Statement from Brian O’Donnell, NZP0012941, p 5.

[451] Statement from Brian O’Donnell, NZP0012941, pp 5-6.

[452] Witness statement of Mr HZ, WITN0324015, para 53.

[453] Te Rōpū Tautoko Marylands Briefing Paper 5, CTH0015243. The Order provided a Briefing Paper summarising the dates when the Order first knew of an Aotearoa New Zealand-based report of abuse against Brother Garchow (and other brothers who ministered in Aotearoa).

[454] Statement from Brian O’Donnell, NZP0012941, p 6.

[455] Witness statement of Mr AR, WITN0901001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 26 April 2022) para 7.18.

[456] Transcript of closing statement of Dr Michelle Mulvihill from the Marylands School public hearing, TRN0000417 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 17 February 2022), p 574.

[457] See our timeline of undisclosed abuse: Cries for help not believed or acted on over almost 40 years

[458] Te Rōpū Tautoko Marylands Briefing Paper 5, CTH0015243, p 16.

[459] Te Rōpū Tautoko Marylands Briefing Paper 5, CTH0015243, p 16.

[460] Victorian Parliament’s Family and Community Development Committee Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Organisations, MSC0006399 (29 April 2013), p 5.

[461] Transcript of Makinson d’Apice Lawyers’ interview of Brian O’Donnell, regarding his handling of sexual abuse complaints, CTH0018408 (19 December 2016), p 6.

[462] Witness statement of Mr AR, WITN0901001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 26 April 2022) para 6.7.

[463] Statement from Brian O’Donnell, NZP0012941, p 5.

[464] Statement from Brian O’Donnell, NZP0012941, p 5.

[465] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 363.

[466] Transcript of evidence of Peter Read, TRN0000416, p 53, pp 519.

[467] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 24 March 2022), para 4.4.

[468] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146001, para 3.14.

[469] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146001, para 4.7.

[470] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146001, para 5.3.

[471] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146001, para 3.14.

[472] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146002, paras 3.11 and 3.12.

[473] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 August 2021), para 2.7.

[474] NZ Police Report Form, Sergeant L F Corbett, regarding outcome of McGrath trial, NZP0014846 (4 February 1993), p 1.

[475] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146002, para 3.23.

[476] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146002, para 3.25.

[477] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146002, para 3.25.

[478] Witness statement of Lew Corbett, WITN1146002, para 46. See also: Letter from Sergeant L F Corbett, NZ Police, to Rachel Adams, NZP0014838 (16 July 1997), p 1.

[479] R v McGrath [2006]; See also Letter from Sergeant L F Corbett, NZP0014838 , p 1;

[480] NZ Police Report Form, NZP0012793, p 2.

[481] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 747.

[482] NZ Police Report Form, NZP0012793, p 1, 5.

[483] NZ Police Report Form, NZP0012793, p 1, 5.

[484] NZ Police Report Form, NZP0012793, p 7, 8.

[485] Second witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838002, para 2.2.

[486] NZ Police Report Form, NZP0012793, p 7–8.

[487] Second witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838002, para 2.4

[488] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 2.5. Second witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838002, para 2.5.

[489] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 11.4.

[490] Second witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838002, para 2.3.

[491] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 2.

[492] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 2.4.

[493] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 5.5.

[494] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 5.4. Second witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838002, para 2.19.

[495] Transcript of evidence of Peter Read at Marylands Hearing, TRN0000416, page 46, pp 512.

[496] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 3.2. This included two of the 1993 complainants.

[497] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, paras 3.2, 3.9.

[498] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 3.12.

[499] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 3.11.

[500] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 3.6.

[501] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 3.7.

[502] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 3.6.

[503] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 3.8.

[504] NZ Police report form from Peter Read, regarding St John of God, Historic Sexual Abuse, NZP0012793, (23 May 2010) p 2–3. See also: NZP0015137, p 13, 22.

[505] NZ Police report form, NZP0012793, (2010) p 8.

[506] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 5.9; See also: Second witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838002, para 2.28

[507] Transcript of evidence of Peter Read at Marylands Hearing, TRN0000416, p 42, 46, pp 508, 512.

[508] Statement of Ken Clearwater, WITN649001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 14 June 2021), para 94. See also: Transcript of evidence of Ken Clearwater from the Marylands School public hearing, TRN0000414 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 14 February 2022), p 53 pp 329.