Chapter Five: Complaints and Accountability (Part 2) Upoko Tuarima: Ngā nawe me ngā Kawenga

Ngā wheako o ngā purapura ora hauā i te punaha manatika

Disabled survivors’ experiences of justice system

242. Of the 58 individuals who reported abuse at Marylands during Operation Authority, 21 or 22 indicated in their formal statements that they had a disability.[768] Police did not keep any systematic data on the nature of those disabilities,[769] nor did they call in specialists to help them communicate with complainants who had a disability.[770] Communication assistants and navigators in the criminal justice system were not in place at the time of the investigation or the trials.

243. In some instances, police did not lay charges because of a complainant’s learning disability. In one instance, police said a complainant had difficulty separating his real-life experiences from what he saw on television, and his evidence was not therefore sufficiently reliable for his case to proceed.[771] A caregiver who accompanied the complainant to a police station confirmed he would confuse what he had seen on television with reality, and a job sheet concluded: “He would in no way be a credible witness given the fact that he confuses reality with television.”[772]

244. Of the 21 complainants who had been recorded by police as having a disability, charges were laid for 18 of them. Detective Superintendent Read considered that a complainant’s disability could have an “indirect impact” on consideration by police and the Crown of whether a complainant would give evidence at trial, and whether charges could be laid. He stated:

“The test is always whether the possible charge meets the Guidelines. Disability may impact in some circumstances on both the evidentiary test and the public interest test. If disability affected a witness’s ability to recall and describe the offending, that would impact on the assessment of whether a matter met the evidentiary test. Where a prosecution is likely to have a very significant negative impact on a complainant, that factor may weight [sic] against laying a charge. Disability may in some circumstances be relevant to assessing the possible impact of a prosecution on a complainant. On the other hand, the seriousness of offending will be aggravated where the offending is against a vulnerable victim. Disability will often mean a victim is more vulnerable, and so this factor may also weight [sic] in favour of laying a charge.”[773]

245. For some disabled complainants who did give evidence, they or their caregivers said the courts failed to take account of their disability or allow them to have caregiver support while giving evidence. They also said the courts made no allowance for their disability during cross-examination and were too quick to disallow their evidence rather than providing appropriate support. The sister of one disabled complainant – whose evidence was subsequently disregarded as unreliable – said she watched her brother give evidence on the stand and was struck by how convincing and animated he was when describing the sexual assaults:

“He was on the stand and proceeded to gesture with his hands that he was anally penetrated; it was not a soft gesture, it was aggressive and violent. I was a bit taken aback. Throughout … his evidence, I was so proud of him getting up there and doing it, but I felt that he was unprotected and looked so vulnerable. I desperately wanted to be up there with him. We were not allowed to be together beforehand, due to suggestibility and contamination of evidence, but I do think that if I had been able to assist him with his evidence, it would have led to a better outcome. I know how to communicate with him and can help him articulate his thoughts.”[774]

246. She said the judge told the jury to set aside her brother’s evidence because his intellectual disability meant he was open to suggestibility. She said her brother would become very agreeable when put under pressure or when he felt stressed:

“Any propositions put to him would have meant he would have just said ‘yes’ and not answered the question properly. If I had been there with him, helping him answer the questions, I believe his answers would have been true.”[775]

247. She gave evidence herself at the trial, and she said the defence lawyer for Brother Moloney was “quite bullying”.[776] He accused her of “trolling for money” and asked why they had waited so long to come forward.[777] She described him as “quite nasty and humiliating” in his manner.[778] Ken Clearwater said he was very upset that Brother Moloney was acquitted on 16 of the 23 charges he faced, and he believed there would have been guilty verdicts on every charge if the survivors had not been disabled.[779]

248. At the trials of Brothers McGrath and Moloney each complainant had to give their evidence about the abuse they suffered from the witness box to a courtroom full of strangers. The protections now commonly used to assist sexual complainants give evidence in alternative ways were not used, such as audio visual links from outside the courtroom, or the use of screens so the witness did not have to confront their perpetrator. Communication assistants were not involved. While those protections were not common place in the mid-2000s when these trials were held, the police and Crown prosecutors did not proactively apply for such directions from the court.

249. Detective Superintendent Read agreed it could be difficult for disabled people to get a fair hearing because criminal trials depended on clear communication, an ability to handle cross-examination, and an understanding of complex procedures in court that can move very quickly.[780] He also said the system did not serve victims of sexual abuse, whether disabled or not. He discussed various potential solutions including having one specially trained person to ask questions of all witnesses, whether for the prosecution or the defence, using written questions that are first reviewed by the presiding judge to make sure that they are not offensive, or having a separate sexual violence court or a separate disabilities court.[781]

Ka whakatakaroatia tā te Rangapū tukanga manaaki i ngā purapura ora

Order’s pastoral process for survivors put on hold

250. The prosecution of Brother McGrath prompted the Order to declare in December 2003 that its pastoral process would consider “no matters, new or old, … until the conclusion of the criminal case next year”.[782] The decision was made by the Order’s Professional Standards Committee, whose members included Brother Burke and Dr Mulvihill.

251. During the depositions hearing for Brother McGrath’s case in 2004, Brother Burke said he stopped the pastoral process after being notified of proceedings against other brothers in Australia and hearings against other brothers in Aotearoa New Zealand.[783] In 2006, he told the High Court the Order halted the process because his legal advisors told him it would not be in the Order’s interests, or those of police, to continue it.[784] Detective Superintendent Read told us he was unaware of any suggestion police had asked the Order to halt the process, saying whether the process continued or halted would have been immaterial to the investigation.[785] The most likely explanation was the one given under oath by Brother Burke to the High Court, namely, that the Order halted the process on the advice of its lawyers, who said it would be in the Order’s interests to do so. To our knowledge, the Order never asked Sir Rodney Gallen whether he considered this step to be appropriate.

252. In February 2004, two months after reaching the decision, the Order made the decision public.[786] Brother Burke made a formal statement that the Order would restart the process once Brother McGrath’s trial was over.[787] He also wrote to many survivors telling them he could no longer meet them because it might be seen as interfering in the criminal justice process.[788] In the meantime, some survivors found their counselling and treatment abruptly cut off.[789]

253. The ‘pause’ was still in place when Brother Graham replaced Brother Burke as Provincial in March 2007, nearly a year after Brother McGrath’s conviction. Brother Graham was opposed to aspects of the pastoral process run by Brother Burke and Dr Mulvihill. Despite the assurances given to survivors that the pastoral process would be re-started, this never happened. Brother Graham instigated a much more formal process that appeared to provide less support to victims.

254. Dr Mulvihill said the Order’s failure to honour its promise to try to rebuild a pastoral relationship with survivors amounted to a “secondary injury”, the first being the abuse at Marylands, Hebron Trust or the orphanage and the second being the breach of trust caused by broken promises of help. She said the Order made a promise to “try and restore their dignity and give them help”, only to abandon them a second time: “I saw that happen over and over again sadly in the coming years.”[790] Brother Graham was highly disparaging about Dr Mulvihill’s criticisms of the Order. In August 2007, he told the Prior General, Brother Donatus Forkan, that he would have no qualms about suing Dr Mulvihill for defamation if she continued her criticisms.[791]

Ka tonoa e te Rangapū tētehi arotake, e whakawhāiti mai ana ki te tukanga whakatakoto nawe

Order commissions review, which is confined to complaints process

255. When the Order’s Oceania senior members gathered for their four-yearly meeting in Australia in March 2007, they elected Brother Graham Provincial, and at the same time also elected at least two brothers facing sexual abuse allegations to its Provincial Council. One of those elected at that time, Brother John Clegg, was convicted in 2015 in Australia on 11 charges of sexual abuse.

256. Their election to the council prompted Dr Mulvihill to write to Brother Forkan in Rome the following month expressing deep reservations about this development.[792] Bishop Michael Malone, chair of the Australian Bishops Committee for Church Ministry, also wrote to Brother Forkan that month. He said Brother Burke had confirmed to him that two newly elected councillors had been accused of sexual abuse. Bishop Malone said the men’s election was a “disturbing matter” and suggested an apostolic visitation authorised by the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life would provide an “independent and authoritative evaluation” of how the Order was being run and could be improved.[793]

257. In May 2007, Brother Graham met Brother Forkan in Rome, and they agreed that a so-called audit of the abuse allegations would be preferable to an apostolic visitation.[794] Brother Graham’s reasons for this were “a properly conducted audit resulting in much more detailed and better researched information than could be expected from an apostolic visitation”.[795]

258. In June 2007, the media in Aotearoa New Zealand reported that Dr Mulvihill was calling for the Order to be shut down. Dr Mulvihill told the Inquiry that soon after she went to The Press newspaper, she received an official letter from Lyndsay Freer, the spokesperson for the Catholic Church, accusing her of bringing “disapprobation” to the Catholic Church. Dr Mulvihill told the Inquiry that she responded by stating:

“It was not I bringing disapprobation, but those men belonging to the St John of God Brothers (and their protectors) who had sexually, physically, emotionally, spiritually and psychologically abused little boys who were in their care in Marylands School.”[796]

259. Brother Graham wrote a letter to two brothers of the Order who were not members of the Oceania province in advance of their meeting with the Congregation for Institutes of Religious and Apostolic Life.[797] The meeting was to discuss “the situation of the Order and the Province in connection with the allegations of abuse”. Brother Graham’s letter enclosed “some background information about the situation” in the province to help with discussions at the meeting. The Inquiry requested the Order provide a copy of this letter. They did not do so, advising they had searched without success for it.[798] This failure of record-keeping prevented us from scrutinising information Brother Graham wanted the meeting to consider.

260. The provincial chapter resolved to set up an independent audit of all aspects of the “abuse issue”, including how the Order handled it and what measures should be put in place to ensure “these matters do not arise again”.[799] However, the review commissioned by Brother Graham was confined to merely examining the Order’s ‘complaints management process’. Sydney consultancy firm Westwood Spice conducted the review and produced a report in September 2008.[800]

261. Many brothers who spoke to Westwood Spice denied anything untoward had ever happened. They expressed disappointment the Order had settled claims made in Victoria. They regarded the claims as spurious and the claimants as lacking the capacity to complain independently. They considered the settlement a betrayal.[801] Mr AR, a former brother said there was a general sense of denial: “I thought the denials and the excuses were just crazy. These guys were guilty as hell, but they could not admit to it.”[802] He said that when Dr Michelle Mulvihill came in to run workshops on the issue of sexual abuse, many of the brothers considered her teachings an absolute affront – “how dare she”.[803]

262. Brother Graham sent a copy of the report to Brother Forkan, along with a draft letter of response.[804] In the draft prepared for his superior to send back to him, he wrote:

“I have been pleased to note that this conclusion of this independent review is that the management process was ‘substantially sound’ and (generally) ‘conducted with the utmost good faith and best intentions’.”[805]

263. Brother Graham intended the Westwood Spice report to be the first phase of the audit, and “future phases will be determined on the information and experience of this first module.”[806] However, no further work was done, including any analysis of the causes of the abuse.

Ka whakahokia e te Rangapū te matatapu, te whakakapinga whakamutunga o ngā whiti mō ngā whakataunga

Order reinstates confidentiality, full-and-final settlement clauses

264. After Brother Graham took over from Brother Burke, the Order resumed a new, more stringent redress process. According to Brother Graham, many brothers were unhappy that the pastoral process had “a total victim focus”.[807] He considered the perpetrators were “secondary victims” and that “justice and compassion [have] been actively denied” to perpetrators.[808] He was also critical of the decision not to require complainants to sign a deed of settlement acknowledging that a payment was without any admission of liability and a full and final settlement of all claims.

265. In August 2008, he wrote to Brother Forkan that he was “quite angry” that Brother Burke and Dr Mulvihill had “refused to bother themselves” with deeds of settlement, and this decision had left the Order unnecessarily exposed legally. He wrote: “I really am getting really tired with New Zealand and the issues involved there!!!!”[809] He explained: “as predicted, some people who were paid out under the Burke-Mulvihill model are now coming back through unscrupulous lawyers to receive more money.”[810]

266. Under Brother Graham’s leadership, the Order has responded to most abuse claims through its Australian lawyers. Claimants must sign a deed of settlement, and an independent lawyer must certify that he or she has advised the claimant before the deed is signed. Brother Graham has also reinstated the practice of adding clauses that require the terms of the settlement not to be disclosed, dropped by the Order in June 2002.[811]

267. Brother Graham has also approved settlements to brothers sexually abused by other brothers. One such settlement was to Brother McGrath, who, in October 2008, sought compensation for the abuse he had been subjected to by Brother Moloney and Brother Berchmans.[812] In 2009, Brother Graham suggested a maximum payment of AUD$250,000 towards what he called the ‘Bernard McGrath project’.[813] In February 2012, Brother Graham approved a payment to Brother McGrath of NZD$100,000. The terms of settlement were confidential, and we were given no documents by the Order that would explain the basis for a payment of this size, or why the payment was higher than many of his victims received.[814] Brother Graham’s evidence did not indicate that there were any planned changes to the Order’s approach to redress, or reasons for any planned changes. It is understood that the Order has entered into a shared services arrangement with the Marist Brothers, but that final authority for any redress to survivors (in respect of alleged abuse by St John of God Brothers) rests with the St John of God Brothers.[815]

268. In Ms Cooper’s meetings with the Marist Brother’s lawyers in March 2022 (being the same lawyer who had acted for the Order, Mr Harrison of Carroll & O’Dea), Mr Harrison and his colleague raised technical legal issues relating to the Limitation Act, Accident Compensation and proof issues, especially in relation to Hebron Trust-related claims. Ms Cooper was advised that payment levels would be made on the basis of “perceived litigation risk”.[816]

269. The Order’s settlement documentation now requires survivors to warrant that all material and/or relevant acts, facts, and circumstances, including “all abuse suffered by [the survivor] at any time has been disclosed and forms part of the claim”. This approach does not acknowledge that survivors often incrementally disclose the abuse they suffered. In addition, the settlement deeds include confidentiality clauses, which the Order has previously said would not be required.[817] Ms Cooper’s view is that the payment offers are now lower than payments to others abused by the Order and who received payments before the Inquiry’s Marylands hearing.[818]

Kāore te Rangapū e hiahia ana ki te hahu ake i ngā pirautanga o ngā mahi tūkino

Order uninterested in getting to root cause of abuse

270. Until very recently, the Order has shown no interest in determining why there have been so many sexual abusers within its ranks in the Oceania province. When pressed, Brother Graham has given various explanations, always without any evidence or analysis. In August 2007, he said sexual abuse within the Order was “largely attributable to the lack of appropriate psycho-sexual assessment and formation of candidates”.[819] In May 2012, he characterised the problem to the Victorian Inquiry as being a number of brothers who operated independently.[820] Brother Graham wrote to the Prior General in Rome where he stated that it wasn’t a widespread or systemic problem at all, but rather the result of actions by “a small number of religious and ex-religious” within the province who were responsible for a “significant betrayal” of its reputation.[821]

271. Brother Graham, when questioned by the Inquiry as to why the Order had not conducted any independent investigation into why Marylands was the centre of such high rates of abuse, stated that their focus had been: “…trying to respond to those victims that are coming forward.”[822] When pressed, Brother Graham acknowledged that it would have been a positive step to investigate the reasons for the high rates of abuse within the Order: “so that this can never happen again.”[823]

272. In further evidence to the Inquiry, Brother Graham conceded that the Order inadequately responded to some allegations of abuse and that:

“The Order recognises that this was wrong. We profoundly regret the abuse that was allowed to happen both because this system was in place and because fundamentally inadequate responses were taken at the time to allegations of abuse”.

However, the takeaway message from Brother Graham was that the systems in place were exploited by certain individuals, not that the systems themselves had failed. When discussing the practice of moving brothers between institutions, Brother Graham stated:

“To our deep regret and shame, we now realise that this system was vulnerable to exploitation by abusers and those who sought to cover up their abuse.”

273. This message was reiterated in Brother Graham’s concluding comments:

“The brothers shamefully acknowledge the great harm that has been perpetrated by some of our members.”

274. Reverend Dr Wayne Te Kaawa (a Presbyterian minister), in his opinion submission to the Inquiry, noticed this and labelled it ‘scapegoating’, and said it was the approach taken by both the Archbishop Paul Martin and Provincial Timothy Graham when providing evidence to the Inquiry. He stated:

“By repeatedly saying, it was only one person, or two people responsible for the abuse, it seems like the Church is setting up a scapegoat(s) to protect the Church. This effectively tries to draw attention away from the other substantial allegations of abuse against the 21 brothers and others.”[824]

275. In April 2013, Brother Graham and Ms Harris, the chair of the Order’s professional standards committee appeared before the Victorian Parliament’s Family and Community Development Committee, where he accepted that the 31 abuse cases in Victoria involving the Order were due to a “systemic failure of scrutiny and accountability”.[825] They were asked whether the Order attracted paedophiles, to which Ms Harris replied that only an investigation into the systemic causes of the abuse could answer that question.[826] When asked whether the Order would be prepared to undertake such an investigation, she replied that it was open to doing so.[827] However, it has never done so, and nor has it ever made any attempt to answer that most obvious and essential question: why have so many brothers in the Order been sexual abusers?

Whakataunga ā-pūtea mō ngā purapura ora

Financial outcomes for survivors

Ngā kerēme i whakatakotongia atu ai ki te Rangapū

Claims made to the Order

276. The Order has made payments to 113 (78 percent) of the 144 individuals who reported abuse by the Order in Aotearoa New Zealand.[828] As at 30 June 2021, payments amount to NZD$7,992,066 (payments were made in Australian dollars and have been converted here using the exchange rate at the time). The average payment was NZD$71,358. By contrast, the average financial payment by other Catholic Church authorities to Aotearoa New Zealand survivors is NZD$24,582.[829]

277. Differences exist in the level of the Order’s payments relative to the setting in which the abuse occurred. The reason for these differences is unclear.

278. Payments totalling NZD$6,639,290 were made by the Order to individuals who reported abuse by brothers at Marylands, the Order’s bach and the orphanage. The average payment was NZD$67,074.

279. Payments totalling NZD$1,769,956 were made to individuals who reported abuse in the care of Hebron Trust. The average payment was NZD$98,331.

280. While the reasons for the difference are not known to the Inquiry, the chance of receiving a payment if the abuse occurred in Hebron Trust context was lower than if abuse occurred in other settings. But, on average, individuals who were abused in Hebron Trust context received a higher level of payment than people abused in other settings.

281. The Order’s payments to Aotearoa New Zealand survivors are lower than it paid to Australian survivors.[830] Brother Graham was not able to explain why.

Ngā kerēme ki te Manatū Mātauranga me te Manatū Whakahiato Ora

Claims made to Ministry of Education and Ministry of Social Development

282. Survivors lodged claims with the Ministry of Social Development and the Ministry of Education in relation to their experiences at Marylands and Hebron Trust. The State has refused to accept responsibility for the abuse perpetrated at Marylands.[831] The redress process for survivors of abuse, operated by the Ministry of Social Development, initially excluded abuse within a facility under the auspices of a faith-based institution. Since 2018 the redress process does not exclude abuse in those settings. However, the State will only acknowledge or apologise for social work practice failures and does not therefore accept responsibility for the abuse suffered.[832]

283. There appears to have been only one claim lodged with the Ministry of Education regarding abuse at Marylands.[833] The Ministry of Education told the victim to approach the Catholic Diocese in Christchurch.[834]

284. The Ministry of Social Development has identified at least six claims that relate to concerns about a claimant’s experience at Marylands, although there may be more.[835] The Ministry of Social Development accepts that at least some social workers failed to supervise children properly, during which time the children suffered sexual abuse.[836]

285. Until November 2018, the abuse endured by the survivors was not considered in settlement payments under the Ministry of Social Development’s full assessment process, though has been in some circumstances including under the Ministry of Social Development’s Two Path Approach since November 2018. [837] The Crown draws a technical distinction between its own failures and the abuse itself. When a claim was received, the Ministry of Social Development considered only whether the social work practices met the standards of the day.[838] For example, if a social worker failed to visit a child as often as they should have done, or failed to investigate an allegation of abuse made by the child, this would be considered to be a practice failure.[839] But the Ministry would take no responsibility for the abuse that resulted from those failures. Survivors have recognised the redress payments, if any, were very low.

“After 12 years in DSW care and nine years fighting the Ministry of Social Development with my lawyers, this offer was like a kick in the head. It was blood money, or chump change. The Ministry basically told me ‘we’re sorry, but we can’t do anything real for you, get on with your life’.”[840]

286. A Hebron Trust survivor, Justin Taia, was under the legal supervision of the Department of Social Welfare for at least 12 months in the period he was being abused.[841] He did not see a social worker for nearly all this time,[842] and the Ministry of Social Development accepts that there was “practice failure” in that he was not supervised properly.[843] However, the apology letter from the Ministry of Social Development did not give any apology for, or recognition of, the abuse that he suffered at Hebron during the time that he was not supervised.[844]

287. Ms Hrstich-Meyer, from the Ministry of Social Development, gave evidence about why redress was provided for “practice failures” but not for abuse that the State failed to notice or act on because of those practice failures:

“…there are a number of reasons for that and bearing in mind this is the thinking at the time, is that many faith-based institutions had their own processes. There was a view that it’s not appropriate to receive multiple payments for the same allegation of abuse. We’re not in a civil context where we’re looking at joint tortfeasors and trying to apportion that.

The other thing is that we presume that the church would have the documentary records, and lastly that it’s more appropriate to get an acknowledgement and apology from that particular organisation.”[845]

288. Cooper Legal has represented a number of Marylands, Hebron Trust and orphanage survivors. It believes that this position is wrong in law, and is a “complete abdication of legal and moral responsibility”.[846] It takes the view that the State has joint responsibility for the abuse, and that it is responsible regardless of whether a child was placed in faith-based care as a State ward, or in the State’s custody, or under its guardianship.[847] Mr Galvin’s own evidence, on behalf of Oranga Tamariki, states that:

“During the period that children were placed at Marylands School, children and young people were able to be placed in State care in accordance with the provisions in the Child Welfare Act 1925, the Guardianship Act 1968, or the Children and Young Persons Act 1974. Those Acts then provided that the CWD [Child Welfare Division] or DSW [Department of Social Welfare] had responsibilities in respect of those children and young people.”[848]

Te Whare Pani o Hato Hōhepa – i roto i ngā puretumu

St Joseph’s Orphanage – Redress

289. The Inquiry has heard from a number of survivors from the orphanage that have shared their experience with the redress process offered by the Sisters of Nazareth.

290. Sister Mary Moynahan told the Inquiry that this redress process was called The Commitment, although confirming that it “has concluded”, she said “The Sisters of Nazareth have entered into a number of settlements with survivors”.[849]

291. The Sisters of Nazareth offered an apology to all orphanage survivors and encouraged these survivors to come forward.[850]

Puretumu torowhānui mō ngā purapura ora

Holistic redress for survivors

292. Survivors are still calling for justice and accountability, an acknowledgment of the pain and harm they suffered, adequate financial compensation, adequate and ongoing holistic support, and to raise awareness in the hope of change:

“I want this abuse to never happen again. The whole thing feels like a horror story, I find it difficult to believe that it could have happened.”[851]

“Peace does not even exist in my world, as there has never been any acknowledgement as to what happened to me as a little boy, an innocent defenseless boy.”[852]

“Justice needs to be done. That includes being paid proper compensation rather than just being shut up and being put aside. This has got to come out.”[853]

Kāore i tika ngā utu paremata

Inadequate financial compensation

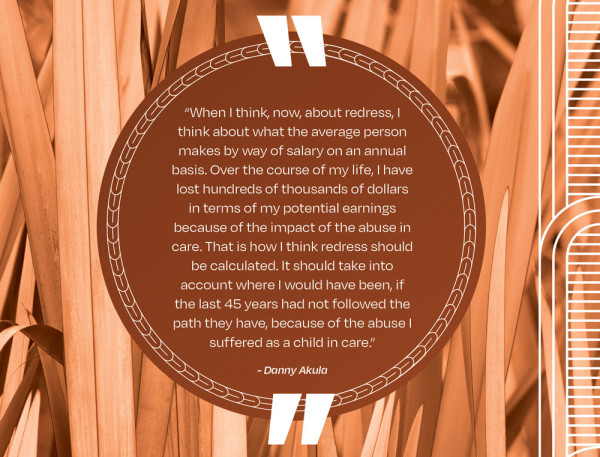

293. Survivors have described the compensation offered by the Order as completely inadequate and are calling for financial redress that is reflective of the impact the abuse and neglect has had on their lives.

“St John of God’s compensation was inadequate to me. They paid some people a lot more than I was paid. I accept that they may claim that they don’t know the full extent of it however I do not feel that what they gave me was sufficient compensation for what I had been exposed to at Marylands.”[854]

“When I think, now, about redress, I think about what the average person makes by way of salary on an annual basis. Over the course of my life, I have lost hundreds of thousands of dollars in terms of my potential earnings because of the impact of the abuse in care. That is how I think redress should be calculated. It should take into account where I would have been, if the last 45 years had not followed the path they have, because of the abuse I suffered as a child in care.”[855]

“All I want is comfort now. I want a house where myself and my children can come and go from.”[856]

“[my sister] says that if the government paid compensation, I could live in a better room in my rest home and have a better quality of life.”[857]

Te hāpai ahurea i roto i ngā puretumu

Culturally appropriate redress

294. The lack of culturally informed redress available for survivors was raised during the hearing when Dr Mulvihill, who assisted the Order with their redress process, was asked whether there was “any consideration given to the policies and the practices of what you might then engage in or was it [te Tiriti o Waitangi] part of the discussions really around your redress processes knowing that you were coming into New Zealand?” Dr Mulvihill replied:

“No...To my shame we did not – I did not know enough, I was ignorant of the culture and the respect that the culture should and could have been paid.”[858]

295. Māori survivor Adam Powell complained about feeling ill-informed and confused about the redress process:

“To be honest, I didn’t really understand much about what was going on... I met with Peter Burke from St John of God at the Star and Garter Pub in October 2002. That’s where he met with quite a few of the complainants. He took notes of our meeting in letter form, but he did not ask about my experience in much detail. I felt that he wanted to deal with us as quickly as he could, the quicker he got us out of there the better. It was difficult to trust him.”[859]

Te hāpai purapura ora i roto i te puretumu torowhānui

Survivor-centred redress

296. Many survivors recommended that any new puretumu torowhānui, holistic redress, process needs to be survivor led. Adam Powell said:

“Any future redress process needs people involved who have an understanding of being a victim. Unless you have been a victim you don’t understand what one goes through. You don’t know what is required to heal, to get through the healing process or even have the belief and strength to disclose in the first place. It must be a survivor led and informed process.”[860]

Te puretumu torowhānui mō ngā purapura ora ki Ahitereiria, ngā wawata mō Aotearoa Niu Tīreni

Redress for survivors in Australia, hopes for Aotearoa New Zealand

297. Darryl Smith is a Marylands survivor and historical child sexual abuse advocate who describes himself as having a mild intellectual disability. Darryl went through a redress settlement process for the sexual abuse he suffered as a child from the Order in Australia and received compensation from the Queensland Government. Darryl shares his experiences of the support he and other survivors of abuse received in Australia:

“If it wasn’t for the courtesy of the Queensland government I wouldn’t be where I am now. That was a recent settlement where my lawyer’s fees were paid, and I received a settlement as well. Queensland has more support for survivors than in New Zealand, take for example the Forde Foundation that was set up after the Inquiry.

At the Lotus Place, there is support there for financial grants, medical costs, dental, start-up costs for a flat and furnishings, educational grants. I received an educational grant for a laptop, for example.

It has a physical location in Brisbane where there is a complete building dedicated to survivors where they can walk off the street, get a coffee, get help, speak to someone.

There’s an 0800 number, there are services available there, like meetings for survivors and cooking classes, all sorts of things going on.

They also help with advocacy for Centrelink, which is Queensland’s equivalent to WINZ. They tell the government what supports survivors need, Lotus Place would meet with Centrelink on behalf of the survivor, or the survivor might be there too. Together they work out what would be available between the state’s interests and the survivor’s needs. Lotus Place shows that they’re there for the long haul.

The Royal Commission Act also shows survivors in Australia that the changes are there for the long haul. New Zealand also needs to commit to redress in legislation.

I have the same hopes for the outcomes for survivors from the Royal Commission in New Zealand.”[861]

298. Like other survivors, Darryl is of the view that redress is much more than financial compensation. As well as sharing his experience in Australia, Darryl has written to the Inquiry urging the Government to establish an independent redress scheme.

299. Darryl’s submission set out features of this proposed redress scheme.[862] Darryl recommends any new redress scheme set up by the Government in response to the Inquiry’s reports must provide for:

› mandatory participation by all faith-based institutions

› the redress scheme being managed independently from the institutions

› historical claims for redress being reviewed and financial compensation being adjusted if necessary.

300. We refer to the Inquiry’s report He Purapura ora, he Māra tipu: From Redress to Puretumu Torowhānui,[863] which recommends the establishment of an independent puretumu torowhānui, holistic redress, system and scheme be set up for survivors of abuse and neglect in care. The Inquiry’s report recommends that faith-based institutions, including the Catholic Church, are strongly encouraged by the State to sign up to the system and scheme. When questioned by the Inquiry, the Catholic Church signalled its support ‘in principle’ for an independent redress scheme.

Ngā takahitanga o te ture tikanga tangata

Potential breaches of human rights law

301. We have found there was pervasive and severe sexual abuse of tamariki and rangatahi at Marylands between approximately 1955 and 1983 and rangatahi at Hebron Trust between approximately 1986 and 1992. The survivors of that abuse suffered severe pain or suffering, both mental and physical. Other abuse had similar effects. Tamaraki and rangatahi were humiliated, forced to act against their will, and lived in fear. All tamaraiki and rangatahi were vulnerable, particularly disabled children.

302. There is evidence that some of the brothers used sexual abuse to punish children, or combined sexual abuse with other acts of punishment and that disabled children were targeted for abuse. We have also found that at Marylands and Hebron Trust there was racism, abusive targeting of tamariki and rangatahi Māori and cultural neglect.

303. The State (Ministry of Education, Department of Health, Department of Social Welfare) provided minimal oversight of these institutions. The Department of Social Welfare and police were put on notice of the alleged abuse at Marylands and Hebron Trust, through complaints they received. When this occurred, the State, through those agencies, did not respond at all or did not respond in a timely way.

304. Many acts of abuse may constitute breaches of the criminal law by the abuser. They may also give rise to civil (tort) law liability for others including the institution or State. In addition, these acts, and failures to address them effectively, may give rise to breaches of human rights law. Potentially relevant human rights and obligations are below:

› The right not to be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment in Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which New Zealand ratified on 28 December 1978.

› Where States have ethnic minorities, persons belonging to those minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, or to use their own language in Article 27 of the ICCPR, which New Zealand ratified on 28 December 1978.

› The State’s obligation to take effective measures to prevent acts of torture contained in the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which Aotearoa New Zealand ratified on 10 December 1989.

› The right not to be subjected to torture or to cruel, degrading or disproportionately severe treatment or punishment in s 9 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990, which has been in force since 25 September 1990.

› The obligation in Article 37 of the United Nation Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Aotearoa New Zealand ratified on 6 April 1993, to ensure that no child is subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

305. In 1982 the United Nations Human Rights Committee issued a General Comment on Article 7 of the ICCPR. The Committee considered that State Parties must ensure effective protection against acts prohibited by Article 7 through “some machinery of control”, including effective investigations of complaints.[864] Such investigations must be prompt, impartial and competently conducted.[865]

306. To be consistent with human rights obligations, a criminal investigation must be capable of establishing the facts and “identifying and punishing those responsible”.[866] The UN Torture Committee has concluded that international legal obligations to investigate alleged torture may apply regardless of whether the alleged acts of torture occurred before or after the State ratified the applicable human rights treaty.[867]

307. In General Comment 31, the United Nation Human Rights Committee stated that it saw implicit in Article 7 of the ICCPR that: “State Parties have to take positive measures to ensure that private persons or entities do not inflict torture, or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment on others within their power.”[868]

308. Sexual offending may constitute torture: rape has been recognised as torture where at least one of the purposes for the rape was a prohibited purpose (to punish, to intimidate or coerce, or for a discriminatory purpose), and the rape was committed by or with the consent of acquiescence of a person acting in an official capacity.[869] There are also sources referring to other forms of sexual abuse,[870] and sufficiently serious corporal punishment,[871] as cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

309. The State’s potential obligations to those in the care of church institutions can be seen in a decision of the European Court of Human Rights in 2014. The court considered Ireland’s obligations to protect children sexually abused in the early 1970s at a school owned by a Bishop of the Catholic Church. The majority of the court referred to the absolute prohibition against torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment as “one of the most fundamental values of democratic society”.[872] It held that State Parties had to: “take measures designed to ensure that individuals within their jurisdiction are not subjected to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment, including such ill-treatment administered by private individuals.”[873] This positive obligation to protect had to be interpreted so that it would not impose an excessive burden on public authorities. However, “the required measures should, at least, provide effective protection in particular of children and other vulnerable persons…” The State was obliged to take “reasonable steps to prevent ill-treatment of which the authorities had or ought to have had knowledge”.[874]

310. The majority held that this positive obligation assumed: “particular importance in the context of the provision of an important public service such as primary education, school authorities being obliged to protect the health and well-being of pupils and, in particular, of young children who are especially vulnerable and are under the exclusive control of authorities.”[875] Ireland could not absolve itself of its obligations to minors in primary schools by delegating its duties to private bodies or individuals, including, in this case, the Catholic bodies responsible for the school.[876]

311. As part of the Faith institutional response hearing in October 2022, the Crown filed a memorandum with the Inquiry stating:

“24. Overseas case law suggests that s 9 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act (right not to be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment) may, independently of s3(b) impose one or both of the following obligations on the State in respect of non-State actors:

24.1 A systemic duty to implement a legal regime that criminalised and punished acts of torture;

24.2 An operational duty to keep children in the care and control of the state safe from known or suspected risks of severe ill-treatment by:

24.2.1 adequately facilitating and investigating complaints of severe ill-treatment; and

24.2.2 adopting reasonable measures and safeguards to protect those children from that risk of severe ill-treatment.”[877]

312. The Crown also stated:

“22. Any one can have obligations in relation to human rights as a result of s3(b) of NZBORA, but only if they are performing a public function, power or duty. This is likely to be the case where the State has empowered private citizens and other actors to provide care for vulnerable children.”[878]

313. The evidence therefore indicates that the Crown may well have breached human rights obligations to those in care at Marylands School, and Hebron Trust. If the Crown is liable, it would be obliged under international law and potentially under the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act to provide appropriate redress including compensation and rehabilitation.

314. There are also potential questions about the liability of the Order of St John of God and members of the Order for abuse of those who received services of Hebron Trust. Liability could potentially arise under the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act for acts done in performance of a public function, power or duty conferred by or pursuant to law after the Bill of Rights came into force on 25 September 1990.[879]

315. There would no doubt be hurdles for any claimant and it is not the Inquiry’s function to determine liability. That is a matter for the courts or other appropriate bodies. But our findings give rise to questions about liability, including for torture and other fundamental human rights breaches. We signal possible recommendations in the Final Report that further steps be taken to determine liability of the Crown, the Order and relevant individuals.

316. In the meantime, we encourage the Crown and the Order to take good-faith steps to assess their liability in light of this report. We also encourage proactive action to ensure that survivors of abuse at Marylands and Hebron Trust have effective and efficient access to justice.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi

317. The current Tiriti o Waitangi legal framework as it applies to the Crown and faith-based institutions providing care for tamariki Māori, rangatahi Māori and pakeke Māori at risk, in the context of faith-based care, can be summarised in the following way:

(a) the Crown has Tiriti obligations as a Tiriti partner/signatory that include:[880]

› Ensuring that faith-based institutions recognise Māori rights and values, and that they act in accordance with te Tiriti obligations of the Crown. This is consistent with te Tiriti principle of active protection and the Crown’s responsibility to ensure its Tiriti obligations are upheld when it delegates its powers and functions to faith-based institutions.

› Monitoring the activities of faith-based institutions, and auditing faith-based institutions’ performance in the context of te Tiriti relationship between Crown and Māori.

(b) faith-based institutions are not Tiriti partners themselves, but:

› Legislation may require them to act consistently with te Tiriti.[881]

› Te Tiriti is relevant to interpreting legislation (or in other words can be read in to legislation) even where legislation is silent on te Tiriti.[882] Therefore, te Tiriti may impact faith-based institutions when they care for tamariki Māori, rangatahi Māori and pakeke Māori at risk as te Tiriti is relevant to the care of tamariki Māori and rangatahi Māori and it colours all legislation dealing with the status, future and control of tamariki.[883]

› If faith-based institutions made their own commitments to te Tiriti (for example, in governing documents of public statements), they may be held accountable to meet those commitments.[884]

318. How te Tiriti applies in a given context depends on the particular circumstances.[885]

319. The status of te Tiriti in Aotearoa New Zealand’s law has evolved overtime so te Tiriti is now recognised as the founding constitutional document of Aotearoa New Zealand and “of the greatest constitutional importance”.[886]

320. In terms of what te Tiriti requires, the Waitangi Tribunal and courts have interpreted and developed a significant body of jurisprudence over the last 40 years. The Waitangi Tribunal, in particular, is a specialist body that has statutory authority to determine the meaning and effect of te Tiriti.[887] Given this expertise, courts have empahsised that much weight should be given to the opinions of the Waitangi Tribunal as expressed in its reports.[888]

321. The Tiriti principles and framework in this report draw on contemporary jurisprudence, some of which emerged after the operation of Marylands and Hebron Trust. This is consistent with the approach taken by the Waitangi Tribunal when assessing historic Crown breaches of te Tiriti: the Tribunal assesses historic Crown conduct against the principles as they are now understood to be. It is also consistent with the operation of the common law.

322. Indeed, te Tiriti rights and obligations have existed since 1840. The principles of te Tiriti are derived from its text, spirit, intent and circumstances. The principles of te Tiriti cannot be divorced from, and necessarily include, the Articles and language of te Tiriti itself.[889] Te Tiriti is always speaking and it is important to stress that the intention of both Māori and the Crown when they signed te Tiriti was to share public power and authority.[890] The Waitangi Tirbunal has found that te Tiriti principles must be based in the actual agreement entered into in 1840 between rangatira and the Crown and the rangatira who signed te Tiriti: did not cede their sovereignty or authority to make and enforce law over their people and within their territories; and agreed to share power and authority with the Governor by way of having different roles and different spheres of influence (the Governor would have authority to control British subjects in New Zealand, and keep the peace and protect Māori interests). [891]

323. The Inquiry is not aware of any relevant te Tiriti commitments made by the Order. The Catholic Church’s National Safeguarding and Professional Standard Committee has committed to “honouring the principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi by working with tangata whenua in the development and implementation of safeguarding practices”. The Church’s “Code of Conduct for Employees & Volunteers” also includes an agreement to “honour the principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi”. However, that code only applies to employees and volunteers in Catholic dioceses and religious institutes, and not to clergy or religious, or employees or volunteers of other lay Catholic organisations. The code of conduct for clergy and religious does not mention te Tiriti.

324. In 1990, Catholic bishops issued a statement acknowledging te Tiriti as providing “the moral basis for the presence of all other peoples in Aotearoa”. The bishops also committed to establishing a Catholic committee to “promote bicultural relationships in our multicultural society” and to implementing two related educational programmes for Catholics.

325. A Statement from the New Zealand Catholic Bishops Conference in 2008 said “[t]he Church will support the cause of all indigenous peoples who seek a just and equitable recognition of their identity and their rights.”

326. Tamariki and rangatahi Māori at Marylands and Hebron experienced institutional racism, targeted abuse and cultural neglect. There was limited knowledge, understanding and acceptance of tikanga Māori and te reo Māori.

327. In our view, the Crown failed to ensure the care provided at Marylands and Hebron Trust was consistent with the principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi. These principles include:

› Tino rangatiratanga – the Māori right to autonomy and self-government, and their right to manage the full range of their affairs in accordance with their own tikanga.[892] Te Tiriti guaranteed Māori the rights and responsibilities their communities possess and practised for generations prior to the signing of te Tiriti.[893] Te Tiriti guaranteed ongoing full authority of Māori over their kāinga (home) encompassing the rights to continue to organise and live as Māori, to cultural continuity where whanaungatanga is strengthened and restored, and to care for and raise the next generation.[894]

› Kāwanatanga[895] – te Tiriti gave the Crown, through the new Kāwana (Governor) the right to exercise authority over British subjects, and keep the peace and protect Māori interests. The duty of the Crown is to foster tino rangatiratanga, not to undermine it, and to ensure its laws and policies are just, fair, and equitable and to adequately give effect to te Tiriti rights and guarantees.

› Partnership[896] – the Crown and Māori are equals with different roles and spheres of influence. Partnership requires the co-operation of both the Crown and Māori to agree to their respective areas of authority and influence, and to act honourably and in good faith towards each other. The Crown is not to decide what Māori interests are or what the sphere of tino rangatiratanga encompasses; the Crown’s duty is to engage actively with Māori (rather than merely consulting), and to ensure shared decision-making with Māori.

› Mutual recognition and respect[897] – the Crown and Māori must recognise and respect the values, laws, and institutions of the other. For the Crown, its recognition and respect of hapū communities, their values, rights, interests and spheres of authority, should be evident in the importance it places on the te Tiriti guarantee of tino rangatiratanga.

› Active protection – the Crown must actively protect Māori rights and interests, including Māori tino rangatiratanga. This includes rights relating to the wellbeing of tamariki, rangatahi, tāngata whaikaha and pakeke whakaraerae. The Crown cannot cause harm, or stand by while harm is done. The active protection of tino rangatiratanga is not a Crown duty arising from its sovereign authority, rather it is an obligation on its part to help restore balance to a relationship that became unbalanced.[898] Because the Crown expanded its sphere of authority far beyond the bounds originally understood by Māori who signed te Tiriti, this duty is heightened so long as the imbalance remains.[899]

› Equity[900] – Māori are guaranteed equitable treatment and citizenship rights and privileges, and the Crown has a duty to actively promote and support both. Equity requires the Crown to focus attention and resources to address the social, cultural, and economic requirements and aspirations of Māori. The Crown must actively address inequities experienced by Māori, and this obligation is heightened if inequities are especially stark. At its heart, satisfying the principle of equity requires fair, not just equal or the same, treatment. This is a duty to be undertaken in partnership with Māori.

328. In our view, the Catholic Church and Order did not ensure the Order’s members recognised the relevance of te Tiriti when caring for tamariki and rangatahi Māori and did not provide care that was consistent with te Tiriti.

Nga Whakakitenga: Kawenga

Findings: Accountability

Te wāhi ki te Kāwanatanga

The role of the State

329. The Royal Commission finds:

a. The State registered Marylands as a private special residential school with knowledge that the brothers were not suitably qualified to teach, but could train and care for disabled boys enrolled at Marylands. The State only carried out minimal monitoring of Marylands.

b. The Order’s operating model was dependent on State funding. If State funding had not been provided, the Order would have not been able to establish, nor continue operating, Marylands school in Aotearoa New Zealand.

c. The Crown failed to ensure the care provided at Marylands and Hebron Trust was consistent with the principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi, specifically tino rangatiratanga, partnership, active protection, kāwangatanga, mutual recognition, respect and equity.

d. Police made poor decisions in 1993 by agreeing not to interview Brother McGrath if he returned to Aotearoa New Zealand, and by later ‘custody clearing’ additional allegations of sexual offending received when he was imprisoned.

e. Social Workers and police failed to investigate, document or act on reports of abuse by boys who ran away, or were wards of the State attending Marylands school and Hebron Trust.

f. The criminal justice system did not ensure access to justice for tamariki and rangatahi, and especially for tamariki and rangatahi Māori and disabled people, including through the provision of accommodations, such as communication assistance or navigations, and there was a lack of culturally appropriate support.

g. The State has failed to accept any responsibility for the harm caused to those abused at Marylands and Hebron Trust.

h. Police failed to provide culturally appropriate processes when engaging with Māori and Pacific survivors during the 2002/2003 Operation Authority investigation.

Te wāhi ki te Hāhi Katorika

The role of the Catholic Church

Te wāhi ki te Pīhopa Katorika o Ōtautahi

The role of the Catholic Bishop of Christchurch

330. The Royal Commission finds:

a. The Bishop of Christchurch failed to properly assess the Order’s suitability to run Marylands as an educational facility.

b. The Catholic Church, Bishop of Christchurch and the Order did not ensure the Order’s members recognised the relevance of te Tiriti o Waitangi when caring for tamariki and rangatahi Māori and did not provide care that was consistent with te Tiriti o Waitangi.

c. The Bishop of Christchurch failed to ensure the Order responded adequately to reports of abuse and claims for redress from 1993, and appeared to be mostly concerned with minimising any harm to the Catholic Church’s reputation.

Te wāhi ki te Rangapū o Hato Hoani o te Atua

The role of the Order of St John of God

331. The Royal Commission finds:

a. The Order failed to prepare the boys placed at Marylands for inclusive community living to enable full and ordinary lives. The education and training provided was not tailored to recognise their different skills and experiences. Students at Marylands spent a lot of their time working in the laundry, kitchen or on the grounds of the school.

b. The Order repeatedly failed to pass allegations of sexual abuse against brothers on to police, in some instances. Instead the Order’s leadership transferred perpetrators elsewhere while taking no steps to safeguard other potential victims from these individuals.

c. The Order missed a clear opportunity to respond to reports of abuse by Brother Moloney and Brother McGrath in 1977. Had the Order taken appropriate action at that time, later prolific offending by these two brothers could have been prevented.

d. If the Order had responded appropriately to the allegations of abuse by Brother DQ in Australia, he never would have been transferred to Marylands to carry out further abuse.

e. The Order’s three provincials at the time, Brother Brian O’Donnell, Brother Joseph Smith and Brother Peter Burke, all failed to act on allegations of sexual abuse involving its members.

f. The Order appeared to have a practice of not making or keeping records of reports of abuse it received about brothers, and more generally. This absence of documentation prevented the Order’s ability to see the true extent of the issues and take appropriate steps in response. It has also meant limited records were kept regarding the ethnicity or disability of boys at Marylands and Hebron Trust.

g. The Order misrepresented that it had acted as soon as allegations were made against Brother McGrath in 1992. Contrary to what the Director of Hebron told the media in 1993, Hebron Trust had not “acted immediately” in relation to the 1992 Aotearoa New Zealand reports of abuse against Brother McGrath. Allegations were made in May and June 1992. Brother McGrath was not removed from his role at Hebron Trust until a brother came from Australia in August 1992 to take him to Australia after an allegation of abuse was made there.

h. The Order’s redress to survivors through its pastoral process had the potential to transform the lives of those traumatised by the abuse. The retraction of the pastoral process in 2004 caused further serious trauma.

i. Neither the Catholic Church nor the Order has ever proactively sought out survivors who attended Hebron Trust facilities and offered help or redress, neither has any successive bishop or Catholic Church entity. Social workers and NZ Police failed to investigate, document or act on reports of abuse by boys who ran away, or were wards of the State attending Marylands School and Hebron Trust.

j. Neither the Catholic Church nor the Order have ever initiated any form of investigation into why abuse at Marylands was so prolific.

[768] Second witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838002, paras 3.8 and 5.2.

[769] Transcript of evidence of Peter Read from the Marylands School public hearing, TRN0000416 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 16 February 2022), p 54–55 pp 520–521.

[770] Second witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838002, para 2.18.

[771] Witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 2.8(d)(i) and second witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838002, para 4.9.

[772] NZ Police Jobsheet, Detective R M Emerson, NZP0030333 (NZ Police, 24 October 2003), p 2.

[773] First witness statement of Peter Read, WITN0838001, para 4.7.

[774] Witness statement of Ms DN, WITN0870001, paras 3.56–3.57.

[775] Witness statement of Ms DN, WITN0870001, para 3.58

[776] Transcript of evidence of Ms DN, TRN0000411, p 97 pp 95.

[777] Transcript of evidence of Ms DN, TRN0000411, p 98 pp 96.

[778] Transcript of evidence of Ms DN, TRN0000411, p 98 pp 96.

[779] Second witness statement of Ken Clearwater, WITN0649002 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 28 January 2022), para 38.

[780] Transcript of evidence of Peter Read, TRN0000416, p 57 pp 523.

[781] Transcript of evidence of Peter Read, TRN0000416, p 57 pp 523.

[782] Hospitaller Order of St John of God Professional Standards Committee Minutes, CTH0012250, p 16. The decision was reaffirmed by the committee in 2004.

[783] Evidence of Peter Burke at Deposition hearing, MSC0008037, p 9 pp 34.

[784] Transcript of McGrath hearing, MSC0007496_00004, p 210.

[785] Transcript of evidence of Peter Read, TRN0000416, p 47 pp 513.

[786] Newsletter from Brother Peter Burke, CTH0015149, p 52.

[787] Newsletter from Brother Peter Burke, CTH0015149, p 52.

[788] Letter from Brother Peter Burke (Provincial) regarding Marylands, CTH0017947 (3 February 2004).

[789] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001,

paras 792, 805, 806.

[790] Transcript of evidence of Dr. Michelle Mulvihill at Marylands School public hearing, TRN0000414 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 14 February 2022) p 26, pp 302.

[791] Letter from Reverend Michael Malone to Brother Donatus Forkan, regarding Apostolic Visitation of the SJOG Australian Province, CTH0019383 (10 April 2007), p 3.

[792] Letter from Dr Michelle Mulvihill to Prior General Brother Donatus Forkan, regarding concerns about sexual abuse allegations against recently elected members, EXT0018237 (2 April 2007), p 1–2.

[793] Letter from Reverend Michael Malone to Prior General, Brother Donatus Forkan, regarding widespread culture of sexual abuse amongst members of the Australian Province of the Brothers of St John of God, CTH0018360 (10 April 2007), p 2.

[794] Letter from Brother Timothy Graham to Prior General Brother Donatus Forkan, regarding articles in the press accusing the Province of inadequate responses to allegations of abuse, CTH0019368 (25 June 2007), p 1.

[795] Letter from Brother Timothy Graham to Prior General Brother Donatus Forkan, CTH0019368, p 1.

[796] Witness statement of Dr Michelle Mulvihill, WITN0771001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 15 September 2021), para 162.

[797] Letter from Brother Timothy Graham to Brother Rudolf Knopp and Brother José Maria Chavarri, CTH0019369 (5 July 2007).

[798] Email from Simpson Grierson (16 June 2022).

[799] Letter from Dr Michelle Mulvihill to Prior General Brother Donatus Forkan, EXT0018237, pp 1–2.

[800] Westwood Spice Report, Report on St John of God Review of Complaints Management Process, CTH0015183 (26 September 2008), pp1–57.

[801] Westwood Spice Report, CTH0015183, p 11.

[802] Witness statement of Mr AR, WITN0901001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 26 April 2022) para 7.18.

[803] Witness statement of Mr AR, WITN0901001, para 7.18.

[804] Letter from Brother Timothy Graham to Brother Donatus Forkan, enclosing the final Westwood Spice Report, CTH0019372 (10 October 2008).

[805] Letter from Brother Timothy Graham to Brother Donatus Forkan, enclosing a letter of response to the Westwood Spice Report, CTH0019375 (19 December 2008), p 1.

[806] Letter from Brother Timothy Graham to Brother Donatus Forkan, providing an update on the management of the professional standards issues, CTH0019366 (10 October 2008), p 1.

[807] Letter from Reverend Michael Malone to Brother Donatus Forkan, CTH0019383, p 2.

[808] Letter from Reverend Michael Malone to Brother Donatus Forkan, CTH0019383, p 2.

[809] Letter from Brother Timothy Graham to Brother Donatus Forkan, enclosing a copy of a video documentary on Bernard McGrath, CTH0019367 (2 April 2009).

[810] Letter from Brother Timothy Graham to Brother Donatus Forkan, CTH0019367 (2 April 2009).

[811] Transcript of evidence of Brother Timothy Graham for the Marylands public school hearing, TRN000415, (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care), 15 February 2022, p 71.

[812] Letter from Brother Bernard McGrath to Brother Timothy Graham, regarding sexual abuse by Brother Rodger Moloney and Brother Berchmans Moynahan, CTH0011944 (23 October 2008).

[813] Letter from Brother Timothy Graham to Lee Robinson of Saunders Robinson Brown, regarding the maximum budget and purchase of a house for the “Bernard McGrath Project”, CTH0016522 (11 September 2009).

[814] Deed of Release between Brother Bernard McGrath and the Trustees of the Hospitaller Order of St John of God and Brother Timothy Graham, regarding the ex-gratia payment to Brother Bernard McGrath, CTH0011956 (no date), p 5.

[815] Updating witness statement of Sonja Cooper, Sam Benton and Caitlin Rabel on behalf of Cooper Legal – relating to redress for historic abuse in state and faith-based care, WITN0831087 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 9 December 2022), para 57.

[816] Updating witness statement of Sonja Cooper, Sam Benton and Caitlin Rabel on behalf of Cooper Legal, WITN0831087, para 63.

[817] Updating witness statement of Sonja Cooper, Sam Benton and Caitlin Rabel on behalf of Cooper Legal – relating to redress for historic abus in state and faith-based care between, WITN0831087 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 9 December 2022), para 72.

[818] Updating witness statement of Sonja Cooper, Sam Benton and Caitlin Rabel on behalf of Cooper Legal, WITN0831087, para 65.

[819] Letter from Reverend Michael Malone to Brother Donatus Forkan, CTH0019383, p 2.

[820] Victorian Parliament’s Family and Community Development Committee Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Organisations, MSC0006399, p 5, 6, 18.

[821] Letter from Brother Timothy Graham to Prior General Donatus Forkan, regarding changes to Brother Brian O’Donnell’s appointment in Papua New Guinea and the Victorian Parliament’s Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Organisations, CTH0015296, p 8.

[822] Transcript of evidence of Brother Timothy Graham, TRN0000415, p 105, pp 466.

[823] Transcript of evidence of Brother Timothy Graham, TRN0000415, p 106, pp 467.

[824] Submission by Reverend Dr Wayne Te Kaawa, WITN1500002, (August 2022).

[825] Victorian Parliament’s Family and Community Development Committee Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by religious and other Organisations, MSC0006399, p 7.

[826] Victorian Parliament’s Family and Community Development Committee Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by religious and other Organisations, MSC0006399, p 18.

[827] Victorian Parliament’s Family and Community Development Committee Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by religious and other Organisations, MSC0006399, p 18.

[828] Possible reasons for financial redress not being made by the Order include: a report of abuse being made recently which has not yet been settled; a report by a parent of an individual that attended Marylands or Hebron where no financial settlement was made; a complainant either stopped correspondence or passed away before settlement.

[829] In terms of value, the total value of all ex-gratia payments made to survivors by 29 Catholic Church authorities is NZD$16,841,558. The value of the payments made by St John of God to survivors (NZD$7,992,066) is 48 percent of all ex-gratia payments. If the ex-gratia payments made to St John of God survivors is excluded, the total amount paid to survivors by other Catholic Church authorities is NZD$8,849,492. The average ex gratia payment made to those 360 survivors who received money from other Catholic Church authorities is NZD$24,582. This average is NZD$46,776 less than the average payment made to St John of God survivors.

[830] Transcript of evidence of Brother Timothy Graham, TRN0000415, p 22 pp 383.

[831] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 775.

[832] Brief of evidence of Linda Hrstich-Meyer for MSD, WITN0102005, paras 4.1–5.5.

[833] Ministry of Education submission in response to the Royal Commission of Inquiry’s Notice to Produce No. 202: Schedule 2, MOE0002844, pp 25–26; Brief of evidence from Helen Hurst (Associate Deputy Secretary, Ministry of Education) for the Marylands School public hearing, EXT0020167 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 7 October 2021), paras 6.1 to 6.12.

[834] Ministry of Education submission in response to the Royal Commission of Inquiry’s Notice to Produce No. 202: Schedule 2, MOE0002844, p 25–26.

[835] Brief of evidence of Linda Hrstich-Meyer for MSD, WITN0102005 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 8 February 2022), para 5.1.

[836] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 43.

[837] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 43.

[838] Brief of evidence of Linda Hrstich-Meyer for MSD, WITN0102005, para 4.1.

[839] Brief of evidence of Linda Hrstich-Meyer for MSD, WITN0102005, para 4.1.

[840] Witness statement of Alan Nixon, WITN0716001, para 33.

[841] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 42.

[842] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 364.

[843] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 364.

[844] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 364.

[845] Transcript of evidence of Linda Hrstich-Meyer for MSD, TRN0000416, p 75–77 pp 541–543.

[846] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 275.

[847] Witness statement of Sonja Cooper and Sam Benton of Cooper Legal, WITN0831001, para 275.

[848] Brief of evidence of Peter Galvin for Oranga Tamariki, WITN1056001, para 12.

[849] Witness statement of Sister Mary Monaghan, WITN1801001 (2023) para 14.

[850] Witness statement of Sister Mary Monaghan, WITN1801001 (2023) para 15.

[851] Witness statement of Mr IH, WITN0671001, para 113.

[852] Witness statement of Mr CA, WITN0721001, para 29.

[853] Witness statement of Steven Long, WITN0744001, para 35.

[854] Witness statement of Edward Marriott, WITN0442001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 24 May 2021), p 20.

[855] Witness statement of Danny Akula, WINT0745001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 13 October 2021), p 39.

[856] Witness statement of Mr HZ, WITN0324015 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 14 May 2021), p 16.

[857] Witness statement of Mr CB, WITN0813001 (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 22 November 2021), p 10.

[858] Transcript of evidence of Dr Michelle Mulvihill, TRN0000414, p 38, pp 314.

[859] Witness statement of Adam Powell, WITN0627001, para 71.

[860] Witness statement of Adam Powell, WITN0627001, para 86.

[861] Witness statement of Darryl Smith, WITN0840001, para 54.

[862] Submission of Darryl Smith, MSC0008833 (20 February 2023) p 1.

[863] He Purapura Ora, he Māra Tipu: From Redress to Puretumu Torowhānui, Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse In Care, December 2021, p 266.

[864] UNHRC General Comment No. 7: Article 7 (Prohibition of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment), 1982 at [1].

[865] UNHRC General Comment No. 20: Article 7 (Prohibition of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment), 1992 at [14].

[866] Zentveld v New Zealand CAT/C/68/D/852/2017 4 December 2019 at [9.2].

[867] Zentveld v New Zealand CAT/C/68/D/852/2017 4 December 2019 at [8.3].

[868] UNHRC General Comment No. 31: The Nature of the General Legal Obligations Imposed on States Parties to the Covenant CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.13 2004 at [8].

[869] For example, see: UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Report on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Committee on Human Rights, E/CN.4/1986/15, 19 February 1986 at [36], [38] and page 29; Raquel Martín de Mejía v. Peru Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Report nº 5/96, Case 10.970, 1 March 1996: “the Commission considers that rape is a physical and mental abuse that is perpetrated as a result of an act of violence […]. The fact of being made the subject of abuse of this nature also causes a psychological trauma that results […] from having been humiliated and victimized. […] Raquel Mejía was raped [in 1989] with the aim of punishing her personally and intimidating her […] The third requirement of the definition of torture is that the act must have been perpetrated by a public official or by a private individual at the instigation of the former. As concluded in the foregoing, the man who raped Raquel Mejía was a member of the security forces […]”; and Prosecutor v Kunarac, Kovac and Vukovic (IT-96-23 & IT-96-23/1-A), International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991, 12 June 2002, Appeals Chamber at [142]-[156].

[870] M.C. v. Poland, European Court of Human Rights, 3 March 2015 at [86]; A and B v. Croatia European Court of Human Rights 20 June 2019 at [106], [110], [111] and [114]; and X and Others v Bulgaria European Court of Human Rights (Grand Chamber) 2 February 2021 at [193].

[871] For example, UNHRC General Comment No. 7: Article 7 (Prohibition of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment), 1982 at [2]; UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Report on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Committee on Human Rights, E/CN.4/1986/15, 19 February 1986 at [48]; and Costello-Roberts v United Kingdom ECHR (25 March 1993) at [30].

[872] O’Keeffe v Ireland European Court of Human Rights (Grand Chamber) 28 January 2014 at [144].

[873] O’Keeffe v Ireland at [144].

[874] O’Keeffe v Ireland at [144].

[875] O’Keeffe v Ireland at [145].

[876] O’Keeffe v Ireland at [150] and [165]-[169].

[877] Memorandum of Counsel of behalf of the Crown: Faith-based institutions response hearing, 21 February 2023, para 24.

[878] Memorandum of Counsel of behalf of the Crown: Faith-based institutions response hearing, 21 February 2023, para 22.

[879] New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990, ss 3(b) and 1(2).

[880] See Waitangi Tribunal Tauranga Moana 1888-2006: Report on the Post-Raupatu Claims

(Wai 215, 2010) at 476.

[881] For example, see: Education and Training Act 2020, ss 4, 5, 9 and 127.

[882] See Trans-Tasman Resources Ltd v Taranaki-Whanganui Conservation Board [2021] 1 NZLR 801, [2021] NZSC 127, paras 8 and 151; Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei Trust v Attorney-General [2022] NZHC 843, para 589; and Huakina Development Trust v Waikato Valley Authority [1987] 2 NZLR 188 (HC).

[883] Barton-Prescott v Director-General of Social Welfare [1997] 3 NZLR 179 at 184.

[884] See Te Pou Matakana Limited v Attorney-General [2022] 2 NZLR 148, [2021] NZHC 2942. Although this case concerned the Ministry of Health’s policy commitments to exercise its powers in accordance with Te Tiriti, it may be arguable that faith-based institutions exercise public powers and functions when providing care and therefore could be amenable to judicial review if a decision is inconsistent with its own Te Tiriti commitments.

[885] New Zelaand Maori Counsil v Attorney-Geneal [1994] 1 NZLR 513 (PC) at 517 (the Broadcasting Assets case); and Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei Trust v Attorney-General [2022] NZHC 843 at [593] and [596].

[886] See New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney-General [1994] 1 NZLR 513 (PC) p 516; Sir Robin Cooke, “Introduction” (1990) 14 NZULR 1, p 1; Huakina Development Trust v Waikato Valley Authority [1987] 2NZLR 188 (HC) pp 206 and 210; and Attorney-General v New Zealand Māori Council (No 2) [1991] 2 NZLR147 (CA) p 149.

[887] Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, Preamble and s 5.

[888] See, for example, New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 (CA) pp 661–662.