Chapter 2: Context

Timeline of the Kimberley Centre

15. The institution that later came to be known as the Kimberley Centre started in 1906 on the outskirts of Taitoko Levin as Weraroa Boys’ Training Farm (Weraroa Boys) for juvenile delinquents.[8] Weraroa Boys operated from 1906 to 1939.[9]

16. Weraroa Boys was established by the Department of Education as an industrial school with occupational training for boys with behavioural problems or who were living in a detrimental environment.[10] In her book about the Kimberley Centre’s history, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre, author Anne Hunt describes Weraroa Boys as a place that was away from public surveillance and ignored by polite society as a place for ‘naughty boys’.[11]

17. Although it was only a small town, Taitoko Levin was home to two other State-run residential institutions for boys: Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre (1950–1985) and Hokio Beach School (1944–1988). The Inquiry has also received evidence from survivors of abuse and neglect in those settings and they are discussed in a separate case study.

18. From 1939 to 1944, the Royal New Zealand Air Force requisitioned the Weraroa Boys’ site for its mobilisation programme for the Second World War.[12] During this period, it was used as an air force base for pilot training.

19. After the war, the buildings were adapted by the Department of Health to accommodate an influx of people with learning disabilities, mirroring the trend of institutional expansion from the 1940s to the 1970s.[13] The Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony opened on the site in July 1945 with 42 young men who had been transferred from the Templeton Farm Colony.[14] It became a ‘home for life’ for many who had been admitted as children and stayed there through their adult years.[15]

20. A special school was opened on site in 1959[16] to provide special education for the “educable subnormal”, in the words of the medical superintendent.[17] The school was opened following a visit from an educational psychologist who noted that the children were not getting any education.[18]

21. The Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony was renamed Levin Hospital and Training School in 1959. Numbers increased during this time and peaked in 1964 at 780.[19]

22. In or around 1972, the institution had 660 children, young people and adults, with approximately 400 children, young people and adults aged 18 years and younger.[20] In 1977, the Levin Hospital and Training School was renamed Kimberley Hospital after the road it was located on, Kimberley Road.[21] In 1979 the institution was home to 759 men, women and children.[22]

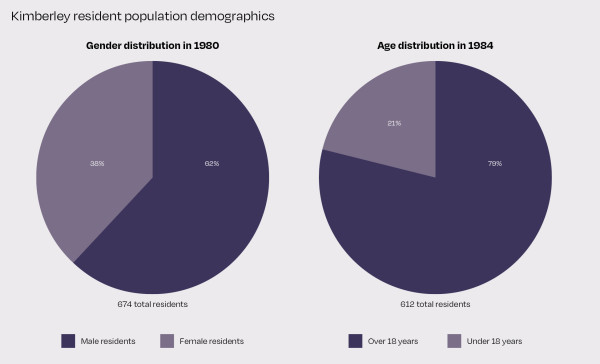

23. Numbers of children, young people and adults progressively declined in the early 1980s as they being transferred into community care. In 1980 there were 733 children, young people and adults at Kimberley Hospital, but by 1985 that number had declined to 600.[23] In late 1982, there were 674 children, young people and adults at Kimberley Hospital; 418 were male (62 percent) and 256 were female (38 percent).[24] Of the 612 children, young people and adults in 1984,[25] 133 were under 18 years old (21 percent).

24. In 1985, the government adopted a policy of community living for people with a learning disability.[26] There was an acknowledgement of the need to close large institutions, but the process was very gradual, taking more than 20 years.[27] There was a considerable period of uncertainty about Kimberley Hospital’s future role from 1985 until the Government announced its closure in 2001.

25. Around 1987, family and whānau of children, young people and adults at Kimberley Hospital began to discuss the institution’s closure. The president of the Kimberley Parents and Friends Association voiced a concern at a meeting that Kimberley Hospital could not be closed because there were some children, young people and adults who would not cope in the community due to the nature or severity of their disabilities.[28] They also said the community would not cope with people from Kimberley. Their concerns reflected a struggle by some parents and whānau to grasp the potential implications of closure.[29] There were concerns about the resources and expertise available to care for people with severe or complex disabilities in a community environment.[30]

26. In 1989, the hospital board changed the name Kimberley Hospital to the Kimberley Centre to reflect a shift from a hospital model with its implication of illness, to normalisation and a focus on lifestyle and developmental services.[31] In 1990, there were 504 Kimberley Centre children, young people and adults ranging from 6 to 79 years old. The average age was 33 years, with 51 children and young people under the age of 20 years.[32]

27. In 1991, 493 children, young people and adults were living at the Kimberley Centre.[33] In 1992, then Health Minister Simon Upton announced that 200 of the remaining 478 children, young people and adults would be moved into the community within the next five years.[34]

28. By 1996, the total number of children, young people and adults had further reduced to 445.[35] In 1997 it was reported that then Health Minister Bill English had said there was not enough money for the shift of 400 children, young people and adults to the community which was estimated to cost $15 million.[36] The Kimberley Centre’s future remained uncertain in the late 1990s. In 1998, the number of children, young people and adults was 416.

29. By the early 2000s there was increasing pressure from families, disabled people and disability rights advocates to close the Kimberley Centre. However, there were some in the community, including some families and staff members, who remained opposed to closure.[37]

30. In September 2001, self-advocacy group People First organised a march on Parliament calling for the Kimberley Centre to be closed. At the march, then-Minister of Disability Issues Ruth Dyson announced that all children, young people and adults of the Kimberley Centre would be resettled in the community over the next four years and the institution would close. At the time of the announcement, there were 375 people living at the Kimberley Centre.[38] Although the deinstitutionalisation movement had started in the 1970s, the Kimberley Centre did not close until 2006.[39]

Societal and attitudinal context

Eugenics and the devaluation of disabled people

31. Whaikaha – Ministry of Disabled People Acting Chief Executive Geraldine Woods acknowledged at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing that: “Between 1950 and 1999 the Health and Disability case settings were ableist. They did not always meet the needs of disabled people and disabled people often experienced discrimination and unfair treatment as a result of their disability. I acknowledge this means disabled people experienced higher levels of abuse and neglect than other people in care.”[40]

32. The Kimberley Centre operated within a socio-cultural context of a false science of eugenics, an ideology that perceived disabled people as inferior beings who should be segregated from society to prevent the reproduction of a ‘subnormal’ race.[41]

33. Government policy followed the Aitken Report, which in 1953 recommended large-scale institutionalisation for the “majority of intellectually handicapped children and adults in the community”.[42] The report recommended parents send their learning-disabled children to a psychopaedic institution at around 5 years old.

34. Expert witness and disability researcher Dr Hilary Stace believes the Aitken Report reflected a toxic mix of societal attitudes of colonisation, racism and eugenics.[43]

35. In 1973, the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Hospital and Related Services: Services for the Mentally Handicapped recommended that patients should be transferred from large institutions to community care. [44] This led to three decades of deinstitutionalisation.[45]

36. By 1977, the Kimberley Centre had become the largest specialist learning disability hospital in the Southern Hemisphere with a resident population approaching 800 people – an estimated 15 percent of all people with a learning disability in Aotearoa New Zealand at the time.[46]

37. While the Inquiry received information on total numbers at the Kimberley Centre at different points in time, the Inquiry received minimal ethnicity data for the Kimberley Centre children, young people and adults over the period of its existence. It appears that ethnicity data was not collected, or if it was collected, it has not been retained. Dr Tristram Ingham, a member of the Kaupapa Māori Panel at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing, told the Inquiry: “There are almost no statistics and certainly no systemic administrative statistics that collect disability status and ethnicity in a way that allows them to identify both.”[47] It is therefore not possible to have a clear picture of how many Māori and Pacific children, young people and adults were in care.

38. The limited ethnicity data the Inquiry has received suggests that in 1989 there may have been 90 Māori children, young people and adults at the Kimberley Centre.[48] A 2007 document, one year after closure, noted that of the 172 former children, young people and adults of the Kimberley Centre now residing in the community in the MidCentral Region, the majority (140) were Pākehā (81 percent), 15 were Māori (9 percent) and one was Pacific (0.5 percent).[49] Across the Inquiry, there has been an issue with a lack of available ethnicity data.

39. Director-General of Health Dr Diana Sarfati told the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing: “Record-keeping issues such as ethnicity not being recorded and the loss of some records have meant that the number of Māori and Pacific people in health and disability care settings during the relevant period is unlikely to ever be known. However, from what we know, Māori and Pacific people and disabled people were particularly negatively impacted, either by being over-represented in these settings or through these settings not meeting their distinct needs, including because of abuse.”[50] Despite the lack of ethnicity data, the Inquiry believes that many Māori were in care at the Kimberley Centre.

40. It was further acknowledged by Whaikaha – Ministry of Disabled People Acting Chief Executive Geraldine Woods that it is likely that Māori, Pacific Peoples and disabled people were disproportionately abused in care.[51]

41. The Inquiry has received no data or evidence from Rainbow and takatāpui survivors of the Kimberley Centre.

Disablism and societal pressure

42. Disablism is the oppression of disabled people.[52] The abuse inflicted on Kimberley Centre children, young people and adults is a prominent example of disablism in Aotearoa New Zealand. Another form of disablism manifested in the fundamental segregation of disabled people out of communities and into an isolated institution with barracks-style mass accommodation. Children, young people and adults were marginalised and excluded from society because of their disability status.

43. The Inquiry commissioned research by the Donald Beasley Institute into the care experiences of people with a learning disability or who are neurodiverse at the Kimberley Centre and other institutions. The research found:

“Abuse of disabled people in care, including (most of) the storytellers in this research can be considered as blatant disablism; they were abused because they were part of a system that created the opportunity for abuse to occur, and they were in that system because they were disabled.”[53]

Timeline of abuse at the Kimberley Centre

- 1939 – 1944 - Royal New Zealand Air Force requisitioned the Weraroa Boys’ site for its mobilisation programme for the Second World War.

- July 1945 - Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony opened on the site with 42 young men who had been transferred from Templeton Farm Colony.

- 1959 - A special school was opened on site in 1959 to provide special education for the “educable subnormal”, in the words of the medical superintendent.

- 1959 - Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony was renamed Levin Hospital and Training School

- 1964 - Numbers peak at 780 people.

- Circa 1972 - The institution had 660 children, young people and adults, with approximately 400 children and young people aged 18 years and under.

- 1977 - Levin Hospital and Training School was renamed Kimberley Hospital after the road it was located on, Kimberley Road.

- 1979 - The institution was home to 759 men, women and children.

- 1985 - numbers have declined to 600 people.

- 1985 - The government adopted a policy of community living for people with a learning disability

- Circa 1987 - Family and whānau of Kimberley Centre children, young people and adults began to discuss the institution’s closure. There were concerns about the resources and expertise available to care for people with severe or complex disabilities in a community environment.

- 1989 - Name changed from Kimberley Hospital to the Kimberley Centre.

- 1990 - There were 504 children, young people and adults ranging in age from 6 to 79 years old.

- 1992 - Health Minister Simon Upton announced that 200 of the remaining 478 children, young people and adults would be moved into the community within the next five years.

- 1996 - Numbers have reduced to 445 people.

- 1997 - Health Minister Bill English said there was not enough money for the shift of 400 children, young people and adults to the community, which was estimated to cost $15 million.

- 1998 - Numbers have reduced to 416 people.

- Early 2000s - Increasing pressure from families, disabled people and disability rights advocates to close the Kimberley Centre, however some were still opposed to closure.

- September 2001 - People First organised a march on Parliament calling for the Kimberley Centre to be closed. Minister of Disability Issues Ruth Dyson announced that all children, young people and adults of the Kimberley Centre would be resettled in the community over the next four years and the institution would close. At the time there were 375 children, young people and adults at the Kimberley Centre.

- 2006 - Although the deinstitutionalisation movement had started in the 1970s, the Kimberley Centre closes.

Footnotes

[8] Brief of evidence prepared by Dr Brigit Mirfin-Veitch for the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 27 June 2022, para 30 and at footnote 4).

[9] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 11).

[10] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, pages 9–10).

[11] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 9).

[12] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 11).

[13] Gates, S, The impact of deinstitutionalisation on the staff of the Kimberley Centre (Donald Beasley Institute, 2008, pages 3 and 8).

[14] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 3).

[15] Mirfin-Veitch, B & Stewart, C, The impact of deinstitutionalisation on the families of the Kimberley Centre residents (Donald Beasley Institute, 2008, page 5), citing Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000).

[16] Mirfin-Veitch, B & Stewart, C, The impact of deinstitutionalisation on the families of the Kimberley Centre residents (Donald Beasley Institute, 2008, page 5).

[17] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 74).

[18] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 74).

[19] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 116).

[20] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 71).

[21] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 156).

[22] Milner, P, An examination of the outcome of the resettlement of residents from the Kimberley Centre (Donald Beasley Institute, 2008, page 30).

[23] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 239).

[24] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 202).

[25] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 242).

[26] Mirfin-Veitch, B & Stewart, C, The impact of deinstitutionalisation on the families of the Kimberley Centre residents (Donald Beasley Institute, 2008, page 6).

[27] Gates, S, The impact of deinstitutionalisation on the staff of the Kimberley Centre (Donald Beasley Institute, 2008, page 3).

[28] Witness statement of David Newman (31 May 2022, page 7, paras 5.12–5.20).

[29] Witness statement of David Newman (31 May 2022, page 7, para 5.20).

[30] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 291).

[31] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 271).

[32] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 289).

[33] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 277).

[34] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 327).

[35] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 321).

[36] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 334).

[37] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 1).

[38] Mirfin-Veitch, B & Stewart, C, The impact of deinstitutionalisation on the families of the Kimberley Centre residents (Donald Beasley Institute, 2008, page 7).

[39] Stace, H & Sullivan, M, A brief history of disability in Aotearoa New Zealand (Office for Disability Issues, 2020, page 13).

[40] Transcript of evidence of Acting Chief Executive Geraldine Woods for Whaikaha – Ministry of Disabled People at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 17 August 2022, page 214).

[41] Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, He Purapura Ora, he Māra Tipu: From Redress to Puretumu Torowhānui, Volume 1 (December 2021, page 41), citing Tennant, M, “Disability in New Zealand: An historical survey,” New Zealand Journal of Disability Studies, 2 (1996, pages 12–15).

[42] Aitken, RS, Caughley, JG, Lopdell, FC, McLeod, GL, Robertson, JM, Tothill, GM & Hull, DN, Intellectually handicapped children report: Report of the consultative committee set up by the Minister of Education in August 1951 (Department of Education, 1953, page 38, para 77(1)).

[43] Witness statement of Dr Hilary Stace (20 September 2019, para 17).

[44] Hutchison, CP, Cropper, J, Henley, W, Turnbull, J & Williams, I, Services for the mentally handicapped: Third report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Hospital and Related Services (The Royal Commission of Inquiry into Hospital and Related Services, 1973, page 15–16).

[45] Stace, H & Sullivan, M, A brief history of disability in Aotearoa New Zealand (Office for Disability Issues, 2020, page 13).

[46] Witness statement of Paul Milner (20 June 2022, para 2.58).

[47] Transcript of evidence of Dr Tristram Ingham from the Kaupapa Māori Panel at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 20 July 2022, page 647).

[48] Letter from general manager, Palmerston North Area Health Board, to chairman and members of the board (25 October 1989) which records that a hui was held with the Kimberley Whānau Group to discuss preparation for Māori residents moving to the community. The letter noted that a small number of the 90 Māori families were represented at the hui.

[49] Memorandum from general manager, Enable New Zealand, to Disability Support Advisory Committee, Enable New Zealand Governance Group (14 September 2007, page 2).

[50] Transcript of evidence of Director-General of Health and Chief Executive Dr Diana Sarfati for the Ministry of Health at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 17 August 2022, page 206).

[51] Transcript of evidence of Acting Chief Executive Geraldine Woods for Whaikaha – Ministry of Disabled People at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 17 August 2022, page 214).

[52] Mirfin-Veitch, B, Tikao, K, Asaka, U, Tuisaula, E, Stace, H, Watene, FR & Frawley, P, Tell me about you: A life story approach to understanding disabled people’s experiences in care (1950–1999), (Donald Beasley Institute, 2022, page 5).

[53] Mirfin-Veitch, B, Tikao, K, Asaka, U, Tuisaula, E, Stace, H, Watene, FR & Frawley, P, Tell me about you: A life story approach to understanding disabled people’s experiences in care (1950–1999), (Donald Beasley Institute, 2022, page 131).