Chapter 4: Nature and extent of abuse and neglect at the Kimberley Centre

The nature of abuse and neglect

70. Survivors of the Kimberley Centre suffered severe and chronic abuse, including neglect, in many different forms during the Inquiry period. Sexual abuse was severe and painful. Physical abuse was normalised. Survivors were psychologically and verbally abused by staff. Neglect was pervasive, meaning neglect of children, young people and adults was experienced across all life domains including psychological and emotional neglect, and physical, cultural, medical, nutritional and educational neglect.

71. This chapter describes the abuse and neglect that survivors of the Kimberley Centre reported to the Inquiry.

Survivors experienced sexual abuse

72. Survivors experienced sexual abuse in care in the Kimberley Centre. This included sexual acts, attempts to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments and advances, and acts to traffic and groom.

73. New Zealand European survivor Mr EI told the Inquiry of witnessing the repeated rape and sexual violation of a number of children at the Kimberley Centre in the early 1960s by a group of members of the public who were regularly granted entry by making payment to nursing staff.[78] The sexual abuse was organised and occurred two to three times a week for a year and a half.[79] The children being abused could not talk or communicate, and were often restrained during the abuse.[80]

74. Mr EI said: “I was woken up by the same woman and taken over to this other room. When we arrived, there were girls and boys there around my age. There were also several adult men and women. There was a girl laying on a bed with no clothes on. The bed looked like an old-fashioned hospital bed. It was on wheels. Her legs were spread apart, with her feet up on things that looked like crutches or braces. They looked like restraints. One of the men got up and had sexual intercourse with her, while we watched. Two other girls were sexually interfered with. They were sexually touched by hand by the adults, while me and this other boy were made to watch. This happened for about an hour. After, I was made to go and wipe down the girls’ private parts and the adults left.”[81]

75. Mr EI described how two Māori girls were targeted by one perpetrator: “Three nights later, I was woken up again around midnight but I am not too sure of the time. We went over to the same place again. I remember there were two Māori girls there. They were in the same position on these beds, with their legs spread apart so they could not close them. This man came in and he turned around and said, ‘My two girls’. Again, sexual intercourse took place. I would come to realise that this man always referred to these two Māori girls as ‘my girls’, and it was always the same man who interfered with these girls.”[82]

76. Mr EI experienced sexual assaults by a nurse at the Kimberley Centre. He was made to sexually abuse other children and female staff members. He witnessed grooming and sexual conduct by a teacher at the Kimberley Centre of girls attending the school.[83]

77. Mr EI ran away from the Kimberley Centre at least twice. On one occasion, he and his friend were picked up by a police officer and taken to Palmerston North Police Station. He described trying to tell a police officer what was happening at the Kimberley Centre, but “no one took any notice of us” and he was just ignored.[84] Mr EI said his friend also tried to tell the police officers about the abuse, but they did not listen to him and similarly ignored him. Mr EI said he does not remember the police officers taking any notes. They were then returned to the Kimberley Centre.

78. The Inquiry has tried to find further information about Mr EI reporting the abuse to NZ Police, but was unable to do so.

79. New Zealand European survivor Ross Hamilton Clark told the Inquiry that he was seriously sexually assaulted with an object by another patient. He was hospitalised and had to be operated on.[85] Ross said: “One day I was going home from the male staff quarters to my villa. Another person, from Villa 2, pushed me into the swimming baths, near the bathing sheds. I told him to leave me alone, but he wouldn’t. He took my pants down and pushed a hose from the shed up my bottom. When the hose was taken out, my bottom was so sore. I’ve never been so sore in my life. It was the worst thing that ever happened to me. They had to ring an emergency doctor from Levin who came and checked what had happened to me. He told me that he had never seen anything like it in his whole life. It looked like my bottom had been cracked open. I had to go to the hospital in Palmerston North, because a big piece of metal from the hose had gotten stuck in me. It had caused an infection and the bleeding. They told me at hospital that this piece would have killed me.”[86]

80. European survivor Miss Howell told the Inquiry about being raped by a male resident at the Kimberley Centre. She didn’t know what was happening as she had never been taught anything about sex education or keeping safe. She reported the rape to a staff member who ensured the male resident didn’t come near her again. However, she wasn’t taken by staff to NZ Police to report the rape.[87]

81. European survivor Sir Robert Martin told the Inquiry that he was sexually abused by a male nurse at the Kimberley Centre. He was so young he didn’t know what was happening.[88] The abuse occurred after Sir Robert had been caught stealing apples. A nurse took him to an office and lectured him about the trouble he had caused, then put his hands down Sir Roberts’ pants and touched him.[89]

82. Expert witness and researcher Paul Milner told the Inquiry that during his time conducting observational research at the Kimberley Centre he heard about a woman from the locked villa who had been taken to hospital to have a pregnancy terminated. In a locked villa, the most obvious way for her to have become pregnant was from sex with a staff member.[90]

83. Allison Campbell worked as a social worker for IHC for many years. She checked on patients in psychiatric and psychopaedic institutions and helped to get them out of institutions. She told the Inquiry about what she had heard from survivors of Campbell Park School and the Kimberley Centre:

“After I gained their trust they told me horrendous stories of sexual, physical and psychological abuse. Different people told me the same stories over and over again. Most went from Campbell Park to Kimberley, and it also happened there.”[91]

Survivors experienced physical and verbal abuse

84. The Inquiry heard from a number of survivors who had experienced physical and verbal abuse. Their bodies were harmed and assaulted, and they were harmed or assaulted often. Physical and verbal abuse might include: aggressiveness towards a person, rough handling, yelling in anger, threats, punching, kicking and hitting (including with objects such as keys), using fire hydrant hoses on children, young people and adults, speaking in a harsh tone, teasing, taunting and , saying harsh or mean things to a resident, swearing at children, young people and adults, and laughing at and bullying at them.

85. Witnesses spoke about staff using fire hydrant hoses on children at the Kimberley Centre. A boy who had soiled himself was hosed down naked by staff using a fire hydrant hose. The boy tried to stand up and was knocked over again. This incident was seen as a warning that if you misbehaved this would happen to you.[92] Ms VC, a training officer at the Kimberley Centre, described witnessing a group of naked boys running around with psychopaedic nurse aides following them. She saw the staff using big fire hoses aimed at the boys to get them back into the ward.[93]

86. Māori survivor Mr HZ (Ngāti Maniapoto and Ngāti Tūwharetoa) was physically assaulted by nursing staff at the Kimberley Centre. He was tied up with his hands hanging over a bar so that he was on tip toes just above the ground. A nurse then kicked him in the stomach.[94]

87. Gay Rowe’s brother, Paul Beale, NZ European, has an intellectual disability that limits his decision-making ability. He was admitted to the Kimberley Centre from age 10 years old in 1961 and spent over 40 years there.[95] Gay visited Paul at the Kimberley Centre and described peer-to-peer assaults and rough handling of children, young people and adults by staff:

“There were often fights going on quite a bit at Kimberley and the attendants only stepped in when they were not going to get injured. Sometimes the residents were handled very roughly by the attendants.”[96]

88. New Zealand European survivor Mr EI said that if children misbehaved, staff would hit them on the head with a set of keys or smack them across the backside.[97]

89. David Newman described his brother, New Zealand European survivor Murray Newman, having bruising to different parts of his body including around his neck and Murray would sometimes explain that a staff member caused the bruising.[98]

90. Caroline Arrell, an NZCare project manager who worked during the deinstitutionalisation of the Kimberley Centre, told the Inquiry she was aware of a psychiatrist using ammonia capsules as a punishment for a person’s failure to respond as required. This involved snapping an ammonia capsule, which contained a chemical with a very strong smell, under a person’s nose. The psychiatrist used ammonia capsules twice on a young woman who was banging her head severely, to try to stop this behaviour. It did not work, and it was later discovered that the young woman had severe pre-existing undiagnosed migraine, which was why she was banging her head.[99]

91. European survivor Sir Robert Martin said that staff would deliberately tease and provoke children, young people and adults to watch them lose control and ‘flip out’.[100] New Zealand European survivor Miss Howell, who went to the Kimberley Centre aged 12 years old, said that the Kimberley Centre staff were mean and would laugh at her and bully her.[101] New Zealand European survivor Ross Hamilton Clark said when his family sent him gifts, especially chocolates, the staff would take them and give him the wrapping paper to taunt him.[102]

92. Researcher Sue Gates from the Donald Beasley Institute noted that some staff were verbally abusive to children, young people and adults: “There are staff that shouldn’t be there … they talk nasty to the residents, they are rude to the residents, they are rude to the staff they work with … and the way they speak to them [residents] it is almost abuse, well it is abuse.”[103] And: “I have seen residents hit, I have seen residents sworn [at] and treated like shit.”[104]

93. Survivor Sir Robert Martin said that punishments were severe and out of proportion to the behaviour.[105] Similarly, Donald Beasley Institute researchers described physical abuse as being quite extreme: “People talked about being beaten by peers frequently and severely. They also clearly identified physical assaults carried out by staff. One survivor describing [sic] dragged down a corridor by either feet or hair as punishment. Sometimes small misdemeanours were met with excessive force, such as being kicked [f]or accidentally breaking something.”[106]

Survivors experienced neglect

94. Neglect is a form of abuse that can take many different forms, such as physical, emotional, educational and cultural neglect. It has been termed a “poverty of experience,”[107] a failure to provide for basic needs or a persistent absence of responsive care. At the Kimberley Centre it included: not providing purposeful activities, not providing education or training, not providing emotional or psychological support, not respecting personal care and dignity, not providing nutritious meals, not providing individualised care, and not providing sufficient medical and dental care. Māori survivors and Pacific survivors experienced cultural neglect.

95. Neglect was universal at the Kimberley Centre, and it was experienced in the daily routines and the institutional culture. Researcher Paul Milner considered the prevalence of neglect to be the real story of the Kimberley Centre:

“The insult of an institution is the depersonalisation and otherwise seemingly purposeless lives that make the events that we more readily recognise as abuse – almost inevitable.”[108]

Survivors experienced dehumanising and disempowering routines

96. Life at the Kimberley Centre was characterised by long periods of inactivity, sitting, standing, staring and snoozing. Observational research found that children, young people and adults spent about 80 percent of their time engaged in no form of purposeful activity.[109] The Kimberley Centre’s own audit recognised the lack of activities and staff engagement with children, young people and adults: “It appeared that staff worked hard to get their general duties done, and no time was given to engaging the residents in some leisure activity .”[110]

97. Adults in the care of the Kimberley Centre spent 70 percent of their time in their villa, and the villa day room represented the limits of their life space.[111] A typical day room was described as a sterile room containing second-hand chairs positioned around the edges of the room. A staff member was seated at a desk. Children sat in the chairs quietly waiting. Some stood or occasionally wandered around the room. On a good day, nothing happened.[112]

98. This description is consistent with survivor and family accounts. Samoan survivor Lusi Faiva described daily life at the Kimberley Centre: “During the day, we sat in the recreational room but there were no activities going on – we hardly interacted with each other. In the shared space there were people of all ages with different disabilities.”[113]

99. European survivor Sir Robert Martin said: “There was nothing to do. Some people stayed on the floor all day rocking back [and] forth. Especially people with the highest needs. There were so many of them, they were just left on the ground.”[114] Anne Bell described the same situation for her sister, Vicki Golder (Pākehā): “From what I saw as an adult, [Vicki] spent a lot of her time in large day rooms. There would be 30 or 40 other people with multiple impairments and a couple of staff. The residents would sit in dated chairs which lined the rim of the rooms.”[115] Former staff member Mr NW said that:

“In between meal time, some of the patients with complex needs were placed on a mattress on the floor in the day room. In the middle of the day, training officers would come in and do movements with people’s body [sic] where possible.”[116]

Survivors experienced educational neglect

100. The Kimberley Centre was portrayed and promoted as a training school for disabled children. The 1964 New Zealand National Film Unit documentary, One in a Thousand, described the Kimberley Centre as a place for training: “The largest group is the trainable subnormal, and for them, a tremendous amount of work is being done. Instead of becoming society’s castaways, with training, these patients are taking their place within the sheltered environment of the hospital community.”[117]

101. The Inquiry heard that many children at the Kimberley Centre did not receive any education or training, let alone at a level appropriate for their needs. An educational psychologist who visited the Kimberley Centre in the 1950s said there was little provided in terms of an education programme and children were not getting any education in the broadest sense.[118] New Zealand European survivor Mr EI described the classroom at the Kimberley Centre in the 1960s as only catering for about 10 out of the approximately 400 children living there at the time.[119] He said the schoolwork was a waste of time for him because it was too basic, and most of the time he was taken out of the classroom and made to do other things, such as making cardboard boxes or coat hangers.[120] Margaret Priest said her sister, New Zealand European survivor Irene Priest, did not attend the small school, nor did she receive training. Margaret said: “It was touted as a training school, it was called a training centre,”[121] but in terms of education or training that was provided for her sister: “There was none. Irene regressed.”[122]

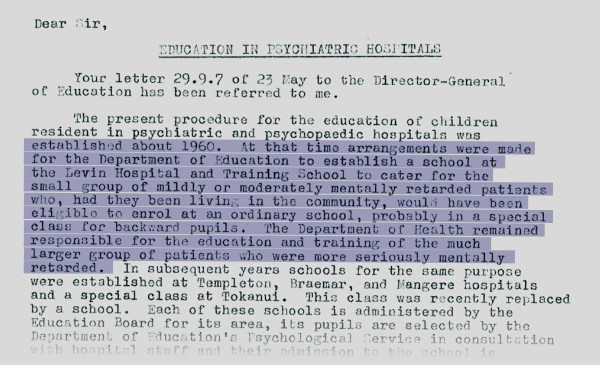

102. A 1973 letter from an officer for special education to the Waikato Hospital Board recorded that: “The present procedure for the education of children resident in psychiatric and psychopaedic hospitals was established about 1960. At that time arrangements were made for the Department of Education to establish a school at the Levin Hospital and Training School to cater for the small group of mildly or moderately mentally retarded patients who, had they been living in the community, would have been eligible to enrol at an ordinary school, probably in a special class for ‘backward’ pupils. The Department of Health remained responsible for the education and training of the much larger group of patients who were more seriously mentally retarded.”[123]

103. European survivor Miss Howell described attending school at the Kimberley Centre and doing painting there, but she cannot recall what else she did at school. She said that children and young people didn’t get taught how to read, and she used to read to others who had not been taught.[124]

104. David Newman told the Inquiry that his brother, New Zealand European survivor Murray Newman, received some schooling at the Kimberley Centre at a day programme, but it was limited: “[Murray] went to the day programme where he was taught colours or numbers in a very limited way. There were occasions when Mum went out there and someone said ‘Oh, we’ve taught [Murray] some colours’ and Mum would say he already knew that.”[125]

105. Meeting minutes of the Palmerston North Hospital Board from 1984 record that:

“Only 14 out of 133 children and young people aged 18 or under attended the school operated by the Department of Education at the Kimberley Centre.”[126]

106. This number was put to Secretary of Education Iona Holsted at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing: “It sounds low, and as we know, there was a whole range of issues around Kimberley and indeed all of those institutions, which led to their closure.”[127] Ms Holsted considered that it was ultimately the Department of Education’s responsibility for the failure to provide children in these settings with an education.[128]

107. Former staff member Mr NW stated that: “It was only a select group of patients who would go to the school, not everybody.”[129] In 1985, there were 90 school-age children and young people at the Kimberley Centre but only 10 were receiving any form of education.[130]

Survivors experienced emotional and psychological neglect

108. European survivor Sir Robert Martin gave evidence about the significant emotional impact that abandonment into an institution had on him: “I was locked away from the community. I wanted to be with my family. I wanted to grow up with my sister – I missed my family, I cried for them. I wanted them to come and take me home but they did not come. So in the end I gave up crying for them.”[131] He discussed the lack of love he felt at the Kimberley Centre: “As a toddler in Kimberley, I was fed and changed and taken care of, but I do not remember being picked up, loved or cuddled because there were so many of us and we were just a number.”[132]

109. European survivor Miss Howell said:

“If I was sad for any reason the staff didn’t give us hugs or anything like that.”[133]

Researcher Paul Milner said: “At Kimberley, staff couldn’t give themselves any opportunity to love or to hold lofty aspirations for the men and women who lived there. It was difficult even to act in ways that recognised and nurtured the very human possibilities of learning and self-expression.”[134]

Survivors experienced neglect of their right to human dignity

110. Human dignity is an inalienable human right, recognised in various international human rights instruments.[135] It is recognised that all human beings have intrinsic worth and mana because they are human. Every person and community is entitled to the same dignity and acknowledgment in society. It includes the prohibition of all forms of inhumane treatment, humiliation and degradation. It also includes the assurance of individual choice, autonomy and decision-making.[136]

111. The right to human dignity was largely not respected at the Kimberley Centre. Attitudes that were prevalent within wider society that devalued disabled people and people experiencing mental distress were compounded and amplified in the institutional setting. Director-General of Health Dr Diana Sarfati acknowledged at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing that: ‘... institutional and societal ableism in legislation, policy and systems has contributed to the abuse of disabled people and people with mental health conditions in health and disability care settings.”[137] Samoan survivor Lusi Faiva said: “I think that the concept of institutions are not set up to care and look after the disabled people because it is built on a system that dehumanises disabled people. And I think that hasn’t changed much for how the current State care works. Care was about medication, changing, showering and other very clinical procedure that does not taken into account of the very individual needs such as human connection and affection.”[138]

112. A job description for a psychopaedic assistant at the Kimberley Centre stated: “Personal cares will be delivered, maintaining privacy and ensuring the resident retains his/her dignity.”[139] However, from the evidence received, the Inquiry is satisfied that privacy and dignity were not respected at the Kimberley Centre. European survivor Sir Robert Martin said:

“We had to treat staff with dignity and respect but they did not treat us in this way.”[140]

The design of communal bathrooms and open toilets with no doors or partitions contributed to a lack of privacy and dignity.[141]

113. The Kimberley Centre’s own internal audit in May 2000 reflected survivors’ descriptions: “The audit team witnessed many residents being cared for in a state of undress without appropriate privacy measures being used.”[142] In relation to one unit, the audit report said: “Dignity and respect need to be maximised as the survey team witnessed as [sic] resident up and undressed as care assistant changed bed. Resident standing covering private parts.”[143]

114. Personal care and support needs were neglected at the Kimberley Centre. If a person with high support needs accidentally soiled themselves, they were left in dirty clothes.[144]

115. The Kimberley Centre evidence demonstrates the gross neglect of a person’s right to be treated and respected as a human being. A Kimberley Centre staff member interviewed by researcher Paul Milner described one person as “not user friendly”. Mr Milner thought the staff member was describing the person as if they were a household appliance and said: “Shit, you’re talking about him like he’s a jug.”[145] This interaction demonstrates an institutional culture that devalued disabled people and failed to respect and protect their’ right to human dignity.

116. There were some exceptions to the predominant neglect of a person’s right to dignity and personhood at the Kimberley Centre. A group of children, young people and adults referred to as the bell-ringers would have each person play a different musical note. They visited rest homes, played their bells and brought enjoyment to their own and other people’s lives. They gifted their music to others and enjoyed the reciprocity involved. Researcher Paul Milner stated that: “Bell ringing was an oasis in a place were almost all of the men and women got no real chance to gift anything.”[146]

Survivors were not treated as individuals

117. Individuality was stripped away. Children, young people and adults of the Kimberley Centre were not dressed in their own clothes, instead they had to share a pool of clothes including underwear. They were colour coded into groups, and all given the same bowl haircuts.[147]

118. People’s names, ethnicities and personal milestones were not recognised or valued. European survivor Miss Howell, who spent more than 30 years at the Kimberley Centre, said she doesn’t recall any celebrations. She said birthdays were like any other day. She does not remember ever having a party or a birthday cake.[148] New Zealand European survivor Mr EI said:

“No one ever celebrated birthdays in these institutions. I never had a birthday at Kimberley.”[149]

119. The internal audit in 2000 noted that healthcare standards were not being met in one of the units: “There is no evidence that care is individualised except in the documentation. There was no evidence that individual needs where [sic] addressed outside prescribed routines.”[150]

120. Another form of neglect of a person’s individual needs can be seen in the account of a Māori man at the Kimberley Centre. Researcher Paul Milner, who worked with and observed this man during the Kimberley Centre’s closure, described him as repeatedly saying: “I’m going home. I’m going home.” A staff member told Mr Milner: “He always does that when he elevates.” Elevating meant that staff saw it as a sign that he was becoming unwell. There was no conversation about home or where his home was.[151] When the person was resettled by Te Roopu Taurima to a home close to his marae, a staff member described a pōwhiri they gave him and told Mr Milner: “It is almost like when he got that pōwhiri he knew he was home … you could feel it, it was like somebody who was lost and came home.”[152]

Survivors experienced nutritional neglect

121. Nutrition was poor at the Kimberley Centre. New Zealand European survivor Irene Priest’s weight fell to 33 kilograms while living at the Kimberley Centre in the 1990s. Her father thought she looked like a “bag of bones” when he saw her.[153]

122. Allison Campbell, who worked as a social worker for IHC to help transition people from the Kimberley Centre into the community, observed staff feeding four disabled adults their dinner from one bowl and using just one spoon. They were being fed at 4pm and would not receive anything else to eat until 8am the next morning.[154] The Kimberley Centre’s audit said:

“It is not appropriate to have Milo made up for patients with cold water several hours before it is given.”[155]

123. Caroline Arrell, an NZCare project manager who worked during the deinstitutionalisation of the Kimberley Centre, was incredulous at the number of people who were given food and fluid directly to the stomach with a feeding tube.[156] Many of the feeding tubes were later assessed as not medically required after the people were discharged from the Kimberley Centre. She found it distressing that some people had feeding tubes inserted due to their complex behavioural needs and dislike of mealtimes.[157]

Survivors experienced inadequate and neglectful medical and dental treatment

124. Dental care provided to children, young people and adults was inadequate, and some survivors received no dental care at all during their time at the Kimberley Centre.

125. NZ European survivor Miss Howell spent more than 30 years in the Kimberley Centre and could not recall ever having a dental check-up or seeing a dentist.[158] Former staff member Mr NW (Ngāti Maniapoto), who worked at the Kimberley Centre for seven years, said: “I don’t remember any of the patients receiving dental care and some of the medication would rot the patients’ teeth.”[159] New Zealand European survivor Mr EI recalled a dentist telling a nurse he was not going to give a child an injection before removing a tooth because “he won’t feel a thing because this person’s got no brains”.[160] The removal of teeth without anaesthetic is a form of physical abuse.

126. Murray Newman’s mother was advised that her son had an ingrown toenail that required medical action. She signed a form allowing Murray to receive a general anaesthetic for the procedure. She was shocked when the medical officer phoned her to advise that the anaesthetic was not required, and her son had been very brave – it only took four men to hold him down.[161] See paragraphs 134-141 for further survivor experiences of abuse relating to other medical matters.

Survivors experienced racial abuse and cultural neglect

Māori experiences of racial abuse and cultural neglect

127. Te Tiriti o Waitangi Treaty of Waitangi provides for the active protection of Māori language and culture. At the Kimberley Centre, survivors’ cultural identities, heritage and language were suppressed, discouraged and undermined.

128. Māori language was not generally understood nor encouraged to be used at the Kimberley Centre. Dr Tristram Ingham, a member of the Kaupapa Māori Panel at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing, spoke about how a staff member noticed that nobody seemed to be paying attention to a Māori boy with Down Syndrome who would mutter all day in language the nursing staff ignored as gibberish. One day the staff member decided to stop and listen to what he had to say, and to her surprise discovered that he was speaking very well in te reo Māori.[162]

129. Being kept at the Kimberley Centre meant that Māori were separated from their whānau, hapū and iwi and therefore their culture. Due to the regimented routines kept and the brisk nature of staff, the Kimberley Centre did not offer emotional support to children, young people or adults in care that they would have expected from a whānau or support network. All of these actions:

- can be seen as a transgression against whakapapa, where Tamariki, rangatahi and pakeke Māori were isolated from the protection of their whānau, hapū and iwi, rendering them particularly susceptible to abuse and neglect[163], and

- contributed to the overall neglect of tamariki and rangatahi Māori.

130. At the Kimberley Centre, whānau hauā me tāngata whaikaha Māori experienced institutional racism, and targeted abuse and neglect.[164]

Pacific Peoples’ experiences of racial abuse and cultural neglect

131. Human rights norms recognise the right of people to enjoy and practise their own culture and language.[165]

132. Pacific survivors experienced cultural neglect at the Kimberley Centre. Samoan survivor Lusi Faiva told the Inquiry about the cultural neglect she experienced at the Kimberley Centre:

“No one ever talked to me about my Samoan heritage. I felt like people didn’t know or care about my Samoan culture. Even if they did there was no recognition, interest or inclusion. There was no respect or effort to recognise me for who I am.”[166]

133. Lusi gave evidence to the Inquiry using her communication device and told the Inquiry that her relationship with her family and culture could have been different had she not gone to the Kimberley Centre: “I would have known more about my mother's earlier life, which would have given me more idea about who she is. The time I went to Kimberley, my mother was still a new migrant from Samoa and she had struggles in settling in this country. At this time, she was in a poignant time in her life and when I was placed in Kimberley, I was at a poignant development phase of my life.”[167] Lusi had no access to her family at the Kimberley Centre, so she felt overwhelmed when she left the institution.[168]

Survivors were overmedicated

134. David Newman explained that his brother, New Zealand European survivor Murray Newman, was heavily medicated as a form of behaviour control by sedation. “[Murray’s] medication was seemingly prescribed in excessive quantities that would then require another medication to counteract the side effects from another medication and so it went on. It became and was a cocktail of medications.”[169] At one point Murray’s weight was around 40–42 kilograms and the dosage of medication he was receiving was “enough to tranquilise a horse”.[170] Murray’s mother worked with an official visitor to have his medication reviewed by an external general practitioner who reported that Murray’s life was at risk and immediate action was necessary.[171]

135. European survivor Sir Robert Martin was given medication not meant for him and this had a long-term impact on his health. “Whatever it was, it had a terrible effect on me. It made me lean on my side. The effects last for a long time. I was sent home. My family thought I was playing up, so I got into trouble but it was the medication. I should never have endured that.”[172]

136. Former staff member Mr NW told the Inquiry about the widespread use of medication at the Kimberley Centre and how, in his view, patients appeared to be overmedicated.

“All Kimberley patients would be given medication each day, usually Melleril or Largactil. This would be established to an appropriate level for the patient. Although I was unregistered, I was allowed to hand out the medication on the afternoon and night shifts. I remember the patients appeared to be overmedicated although I was unqualified at the time so I’m probably not the best person to make judgment. They were very drowsy and their mouths were very dry.”[173]

137. New Zealand European survivor Irene Priest received significant quantities of medication, including antipsychotic medication, despite never having any psychiatric diagnosis. Dr Martyn Matthews provided an expert opinion to the Inquiry on the use of psychotropic medication and reviewed Irene’s medical records.[174] Dr Matthews said: “I have found no documented evidence of additional psychiatric diagnosis that would warrant the prescription of psychotropic medications. It appears that, despite the family’s concerns about over-sedation and side effects, these medications continued to be prescribed and administered for behavioural reasons.”[175] Dr Matthews noted that antipsychotic drugs were often used for people with a learning disability for their sedative properties rather than their antipsychotic properties in order to manage agitation and other behaviours.[176]

138. Research conducted by Dr Brigit Mirfin-Veitch identified reports that medication was used as a form of chemical restraint and as a form of punishment.[177]

139. A 1978 media article reported that the Citizens Commission on Human Rights had received complaints from Kimberley Centre staff about the experimental use of high doses of a drug called psilocybin on mentally handicapped children at the Kimberley Centre. Psilocybin was said to possess hallucinogenic properties similar to those of the drug lysergide, commonly known as LSD.[178] The Citizens Commission on Human Rights called for an investigation.

140. In February 1979, then Minister of Health George Gair wrote to the Citizens Commission on Human Rights informing them that there was a technical breach of the Misuse of Drugs Act because when psilocybin was first administered it didn’t have ministerial approval. However, approval was retrospectively granted, and parental consent was given for use of the drug at the time.[179]

141. In February 1992, the Manawatu-Wanganui Area Health Board informed the Citizens Commission on Human Rights that at least two patients had been treated between 1978 and 1979 with LSD or psilocybin for schizophrenic illnesses.[180]

Survivors experienced seclusion

142. Researcher Paul Milner described four locked villas at the Kimberley Centre, one for women and three for men, where individuals had to ask for permission to leave. He described one villa for men as a concrete unit with double locked doors, high windows with mesh over them, and not enough chairs in the day room. The men locked into this villa spent 90 percent of their time in the day room where they had nothing to do. He compared this to being imprisoned and yet these men “had done nothing wrong other than to be born with a learning disability.”[181]

143. Margaret Priest believes that her sister, New Zealand European survivor Irene Priest, was placed in seclusion at the Kimberley Centre as punishment for her behaviour.[182] Irene’s records show that over a 10-week period in 1990 she was placed in seclusion 18 times; 13 times were for getting up too early in the morning.[183]

144. Former staff member Mr NW described what being placed in seclusion was like at the Kimberley Centre.

“Where a patient became violent, we would put them into the seclusion room. This room had a mattress on the ground and a pot for the toilet. There were windows in the room, but usually there were shutters across the window and, depending on the nature of the patient, that window would be either be locked or unlocked.”[184]

Mr NW said patients were sedated in seclusion until they calmed down which could take five to seven days.[185]

145. The internal audit of the Kimberley Centre in 2000 noted that a lack of staff numbers at night resulted in individuals being locked in the day room with the lights off. It was recommended this practice cease immediately.[186] In relation to one of the villas, the audit said:

“The locking up of clients and leaving them unattended would be seen to constitute abuse and neglect as defined by the company policy. Hawea as a unit has some resident [sic] with particularly challenging behaviour at night … staffing levels need to recognise this fact.”[187]

146. Both Acting Chief Executive of Whaikaha – Ministry of Disabled People Geraldine Woods and Director-General of Health Dr Diana Sarfati acknowledged to the Inquiry's State Institutional Response Hearing that there was inappropriate use of seclusion and restraint in psychopaedic settings.[188]

The extent of abuse and neglect

147. The Kimberley Centre did not collect complaint data before 1994, therefore it is not possible for the Inquiry to accurately report on the extent of abuse at the Kimberley Centre. However, the evidence received shows that abuse and neglect was prevalent. Further, for Tell Me About You, the Donald Beasley Institute’s research report into the care experiences of people with a learning disability or who are neurodiverse at the Kimberley Centre, the Institute interviewed 16 people about their experience in care and concluded that disabled people experienced bullying, emotional / psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, medication abuse, cultural abuse, neglect, that this abuse pervasive and violent, and that it could be blatant and covert.[189]

148. Researcher Paul Milner told the Inquiry: “For some people if you walked up to them really quickly they would cower and cringe, the clear implication being that they had been assaulted previously and in the vernacular of Kimberley this was kind of known as the ‘Kimberley cringe’.”[190] New Zealand European survivor Mr EI gave evidence about the Kimberley cringe. He described kids cowering and protecting their face and head with their arms when staff members came near them to protect themselves from being hit in the head.[191] The ‘Kimberley cringe’ exemplifies the extent of abuse at the Kimberley Centre. It demonstrated the normalised acceptance of physical abuse at the Kimberley Centre and its impact on individuals.

149. Social worker Allison Campbell, who helped transition individuals out of the Kimberley Centre into the community, told the Inquiry: “I believe a lot of residents who came out of Kimberley were used to being hit. There was only once [sic] occasion where I actually witnessed a staff member hitting someone at Kimberley. The way the person responded to being hit indicated to me that he was used to his happening. He acted as if it was normal, he just took it. I remember he did not ask why the staff member had hit him.”[192]

150. Researchers Dr Brigit Mirfin-Veitch and Dr Jennifier Conder described another example of the Kimberley cringe that illustrated the fear provoked by frequent abusive treatment. A sister visiting her brother was informed that patting his hand provoked a fearful response because he thought he was being disciplined or hurt.[193]

Footnotes

[78] Witness statement of Mr EI (20 February 2021, pages 5–9).

[79] Witness statement of Mr EI (20 February 2021, paras 2.39–2.40).

[80] Witness statement of Mr EI (20 February 2021, para 2.52).

[81] Witness statement of Mr EI (20 February 2021, pages 5–6).

[82] Witness statement of Mr EI (20 February 2021, para 2.35).

[83] Witness statement of Mr EI (20 February 2021, para 2.48).

[84] Witness statement of Mr EI (20 February 2021, para 2.6–-2.66).

[85] Witness statement of Ross Hamilton Clark (15 February 2022, page 2).

[86] Witness statement of Ross Hamilton Clark (15 February 2022, page 2, paras 2.5–2.8).

[87] Witness statement of Miss Howell (26 January 2022, page 4, para 2.28).

[88] Transcript of evidence of Sir Robert Martin at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 November 2019, page 700).

[89] McRae, J, Becoming a person: The biography of Robert Martin (Craig Potton Publishing, 2014, page 34).

[90] Witness statement of Paul Milner (20 June 2022, para 2.8).

[91] Witness statement of Allison Campbell (15 February 2022, page 12, para 2.44).

[92] Transcript of evidence of Sir Robert Martin at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 November 2019, page 700).

[93] Witness statement of Ms VC (13 October 2020, pages 12–13).

[94] Witness statement of Mr HZ (14 May 2021, page 4, para 15).

[95] Affidavit of Gay Rowe (12 February 2020, page 1, paras 2 and 5).

[96] Affidavit of Gay Rowe (12 February 2020, page 2, para 8).

[97] Witness statement of Mr EI (20 February 2021, para 2.26).

[98] Witness statement of David Newman (31 May 2022, paras 5.31–5.37).

[99] Witness statement of Caroline Arrell (21 March 2022, page 5, para 2.15).

[100] Witness statement of Sir Robert Martin (17 October 2019, para 29).

[101] Witness statement of Miss Howell (26 February 2022, page 4, para 2.31).

[102] Witness statement of Ross Hamilton Clark (15 February 2022, page 2, para 2.13).

[103] Gates, S, The impact of deinstitutionalisation on the staff of the Kimberley Centre (Donald Beasley Institute, 2008, page 35).

[104] Gates, S, The impact of deinstitutionalisation on the staff of the Kimberley Centre (Donald Beasley Institute, 2008, page 35).

[105] Witness statement of Sir Robert Martin (17 October 2019, para 26).

[106] Transcript of evidence of Dr Brigit Mirfin-Veitch at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 1 November 2019, page 417).

[107] Brief of evidence of Dr Simon Rowley (17 August 2022, page 2).

[108] Witness statement of Paul Milner (20 June 2022, para 2.9).

[109] Witness statement of Paul Milner (20 June 2022, para 218); Milner, P, An examination of the outcome of the resettlement of residents from the Kimberley Centre (Donald Beasley Institute, 2008, page 124).

[110] MidCentral Health, Internal audit: Audit of the residential units at the Kimberley Centre (July 2000, page 3).

[111] Witness statement of Paul Milner (20 June 2022, para 2.16); Milner, P, An examination of the outcome of the resettlement of residents from the Kimberley Centre (Donald Beasley Institute, 2008, page 89).

[112]Witness statement of Paul Milner (20 June 2022, para 2.17).

[113] Witness statement of Lusi Faiva (15 June 2022, page 1).

[114] Witness statement of Sir Robert Martin (17 October 2019, para 22).

[115] Witness statement of Anne Bell (16 May 2022, page 4, para 2.18).

[116] Witness statement of Mr NW (31 May 2022, page 4, para 3.7).

[117] New Zealand National Film Unit, One in a Thousand (1964), https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/one-in-a-thousand-1964/availability.

[118] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 74).

[119] Transcript of evidence of Mr EI at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 11 July 2002, page 51).

[120] Transcript of evidence of Mr EI at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 11 July 2002, page 51).

[121] Transcript of evidence of Irene Priest and Margaret Priest at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 11 July 2022, page 22).

[122] Transcript of evidence of Irene Priest and Margaret Priest at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 11 July 2022, page 24).

[123] Letter from officer for special education to secretary, Waikato Hospital Board, Re: Education in psychiatric hospitals (11 June 1973, page 1).

[124] Witness statement of Miss Howell (26 February 2022, page 3, paras 2.11–2.12).

[125] Witness statement of David Newman (31 May 2022, para 5.79).

[126] Meeting minutes of the Palmerston North Hospital Board (1984, page 3).

[127] Transcript of evidence of Secretary for Education and Chief Executive Iona Holsted for the Ministry of Education at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 18 August 2022, page 386).

[128] Transcript of evidence of Secretary for Education and Chief Executive Iona Holsted for the Ministry of Education at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 18 August 2022, page 386).

[129] Witness statement of Mr NW (31 May 2022, page 5, para 3.11).

[130] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 283).

[131] Transcript of evidence of Sir Robert Martin at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 November 2019, page 697).

[132] Transcript of evidence of Sir Robert Martin at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 November 2019, page 697).

[133] Witness statement of Miss Howell (26 January 2022, page 3, para 2.16).

[134] Witness statement of Paul Milner (20 June 2022, para 3.6).

[135] See the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 1; International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 10(1); the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Article 16(4).

[136] Clapham, A, Human rights obligations of non-state actors (Oxford University Press, 2006, pages 545–546), in McCrudden, C, “Human dignity and judicial interpretation of human rights,” The European Journal of International Law, Volume 19, No 4 (2008, page 686).

[137] Transcript of evidence of Director-General of Health and Chief Executive Dr Diana Sarfati for the Ministry of Health at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 17 August 2022, page 206).

[138] Witness statement of Lusi Faiva (15 June 2022, page 2).

[139] Job description of a psychopaedic assistant received from the Mid Central District Health Board (n.d., page 2).

[140] Transcript of evidence of Sir Robert Martin at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 November 2019, page 711).

[141] Transcript of evidence of Sir Robert Martin at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 November 2019, page 699); Witness statement of Miss Howell (26 January 2022, page 3, para 2.18).

[142] MidCentral Health, Internal audit: Audit of the residential units at the Kimberley Centre (July 2000, page 3).

[143] MidCentral Health, Internal audit: Audit of the residential units at the Kimberley Centre (July 2000, page 36).

[144] Transcript of evidence of Sir Robert Martin at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 November 2019, page 699).

[145] Witness statement of Paul Milner (20 June 2022, para 2.44).

[146] Witness statement of Paul Milner (20 June 2022, para 2.86).

[147] Transcript of evidence of Sir Robert Martin at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 November 2019, page 699).

[148] Witness statement of Miss Howell (26 January 2022, page 3, para 2.10).

[149] Witness statement of Mr EI (20 February 2021, para 2.13).

[150] MidCentral Health, Internal audit: Audit of the residential units at the Kimberley Centre (July 2000, page 6).

[151] Witness statement of Paul Milner (20 June 2022, para 2.78).

[152] Witness statement of Paul Milner (20 June 2022, para 2.82).

[153] Witness statement of Margaret Priest (28 January 2022, para 2.15).

[154] Witness statement of Allison Campbell (15 February 2022, page 9, para 2.30).

[155] MidCentral Health, Internal audit: Audit of the residential units at the Kimberley Centre (July 2000, page 21).

[156] Witness statement of Caroline Arrell (21 March 2022, page 8).

[157] Witness statement of Caroline Arrell (21 March 2022, pages 8–9).

[158] Witness statement of Miss Howell (26 January 2022, page 3, para 2.22).

[159] Witness statement of Mr NW (31 May 2022, page 5, para 3.10).

[160] Transcript of evidence of Mr EI at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 11 July 2002, page 52).

[161] Witness statement of David Newman (31 May 2022, page 11, para 5.60).

[162] Hunt, A, The lost years: From Levin Farm Mental Deficiency Colony to Kimberley Centre (Nationwide Book Distributors, 2000, page 318).

[163] Dr Ingham from the Kaupapa Māori Panel spoke of institutions such as the Kimberley Centre being primarily places of detention and isolation, in Transcript of evidence of Dr Tristram Ingham from the Kaupapa Māori Panel at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 20 July 2022, page 647).

[164] Witness statements of Mr EI (20 February 2021, para 2.35); Mr HZ (14 May 2021, page 4, para 15) and Mr NW (31 May 2022, page 5, para 3.13); Kimberley Needs Assessment Team, Needs assessment of [survivor] (13 May 2000).

[165] Clapham, A, Human rights obligations of non-state actors (Oxford University Press, 2006, pages 545–546), in McCrudden, C, “Human dignity and judicial interpretation of human rights,” The European Journal of International Law, Volume 19, No 4 (2008, page 686).

[166] Witness statement of Lusi Faiva (15 June 2022, page 1).

[167] Transcript of evidence of Lusi Faiva at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 19 July 2022, page 554).

[168] Transcript of evidence of Lusi Faiva at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 19 July 2022, page 552).

[169] Witness statement of David Newman (31 May 2022, pages 7–8); Transcript of evidence of David Newman at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 12 July 2022, pages 91–92).

[170] Transcript of evidence of David Newman at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 12 July 2022, page 92).

[171] Witness statement of David Newman (31 May 2022, pages 12–13).

[172] Transcript of evidence of Sir Robert Martin at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 November 2019, pages 705).

[173] Witness statement of Mr NW (31 May 2022, page 5, para 3.15).

[174] Matthews, M, The medicalisation, use of psychotropic medications and seclusion and restraint for people with a learning disability and / or autism spectrum disorder, Expert opinion prepared for the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (7 August 2022, page 10).

[175] Matthews, M, The medicalisation, use of psychotropic medications and seclusion and restraint for people with a learning disability and / or autism spectrum disorder, Expert opinion prepared for the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (7 August 2022, page 10, para 4.20).

[176] Matthews, M, The medicalisation, use of psychotropic medications and seclusion and restraint for people with a learning disability and / or autism spectrum disorder, Expert opinion prepared for the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (7 August 2022, page 5, para 2.4).

[177] Brief of evidence prepared by Dr Brigit Mirfin-Veitch for the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 27 June 2022, pages 16–17); Mirfin-Veitch, B & Conder, J, Institutions are places of abuse: The experiences of disabled children and adults in State care between 1950–1992 (Donald Beasley Institute, 2017, page 41).

[178] “Complaints about drug experiments on mentally retarded children,” The 8 O’Clock Auckland Star (25 November 1978).

[179] Letter from the Minister of Health to the secretary, Citizens Commission on Human Rights (23 February 1979).

[180] Letter from general manager, Manawatu-Wanganui Area Health Board, to research officer, Citizens Commission on Human Rights (14 February 1992).

[181] Transcript of evidence of Paul Milner at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 12 July 2022, page 122).

[182] Witness statement of Margaret Priest (28 January 2022, para 2.32).

[183] Transcript of evidence of Irene Priest and Margaret Priest at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 11 July 2022, page 31).

[184] Witness statement of Mr NW (31 May 2022, page 5, para 3.17).

[185] Witness statement of Mr NW (31 May 2022, page 5, para 3.18).

[186] MidCentral Health, Internal audit: Audit of the residential units at the Kimberley Centre (July 2000, page 6).

[187] MidCentral Health, Internal audit: Audit of the residential units at the Kimberley Centre (July 2000, page 8).

[188] Transcript of evidence of Acting Chief Executive Geraldine Woods for Whaikaha – Ministry of Disabled People at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 17 August 2022, page 216); Transcript of evidence of Director-General of Health and Chief Executive Dr Diana Sarfati for the Ministry of Health at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 17 August 2022, page 207).

[189] Mirfin-Veitch, B, Tikao, K, Asaka, U, Tuisaula, E, Stace, H, Watene, FR & Frawley, P, Tell me about you: A life story approach to understanding disabled people’s experiences in care (1950–1999), (Donald Beasley Institute, 2022, page 17).

[190] Transcript of evidence of Paul Milner at the Inquiry’s Ūhia te Māramatanga Disability, Deaf and Mental Health Institutional Care Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 12 July 2022, page 111).

[191] Witness statement of Mr EI (20 February 2021, para 2.27).

[192] Witness statement of Allison Campbell (15 February 2022, page 11, para 2.42).

[193] Mirfin-Veitch, B & Conder, J, Institutions are places of abuse: The experiences of disabled children and adults in State care between 1950–1992 (Donald Beasley Institute, 2017, page 37).