Chapter 10: State-based care settings during the Inquiry period Ūpoko 10: Ngā whakaritenga taurima ā-Kāwanatanga i te wā Pakirehua

411. Throughout the Inquiry period there were many different State care settings, managed by different government departments and involving a huge range of different staff, professions, legislation, policy and practice. A single survivor could move from foster care to a children’s short-stay facility, to a long-term facility and then on to a borstal, corrective training or a psychiatric institution.

Tokoora Pāpori

Social welfare 1950–1999

Te ture Tokoora Tamariki

Child Welfare legislation

412. There were three key Acts across the Inquiry period governing child welfare and out of home placements. The first was the Child Welfare Act 1925.[502] The 1925 Act did not separate the care and protection of children from youth justice issues. Whether children and young people had broken the law or were in an unsuitable home environment, the State viewed them as in need of care and protection.[503]

413. The Children and Young Persons Act 1974 replaced the Child Welfare Act 1925. Like the 1925 Act, the 1974 Act did not distinguish between youth justice and care and protection. The 1974 Act did, however, distinguish between children (those under 14 years old) and young people (15 to 16 years old) with the intention of diverting children away from the court system.[504]

414. The Children, Young Persons and Their Families 1989 Act placed a focus on working with a child’s whānau in an attempt to give them more authority and power to make decisions about their children. That decision-making process was intended to be bolstered by the establishment of family group conferences where whānau could participate in the decision-making process.[505]

Te Tari me āna kaiārahi

The Department and its leadership

415. Departmental responsibility for administering child welfare legislation underwent several changes during the Inquiry period. For the first two decades of the Inquiry period, the Child Welfare Branch within the Department of Education was responsible for the welfare of all children and young people, under the Child Welfare Act 1925.[506]

416. From 1972, the newly established Department of Social Welfare took over responsibility for child welfare from the Department of Education. The Children and Young Persons Act 1974 governed the department’s work until 1989, with the introduction of the Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989.

417. Between 1950 and 1999, the following people were responsible for the administration of child welfare in New Zealand:

- between 1950 and 1972, the superintendent of the Child Welfare Division within the Department of Education. The superintendent was appointed by the State Services Commission and was answerable to the Minister of Education through the Director of Education.[507] The superintendent was responsible for administering the Child Welfare Act 1925, Part V of the Infants Act 1908 relating to Infant homes,[508] as well as the Child Welfare Division of the Department of Education.[509]

- The Child Welfare Act 1925 encouraged the use of community-based care rather than institutional care through the use of supervision orders where a Child Welfare Officer (social worker from 1971) would monitor a child at home.[510] Under this Act, the superintendent could become the person responsible for children and young people if the superintendent entered an agreement with a parent or other guardian to take responsibility for a child or young person.[511] Judges in the Children’s Court could also make a committal order, making the superintendent responsible for the care of children and young people.[512] Under either of these arrangements, the superintendent became the sole guardian of the child or young person[513] and had a duty to act with due expertise, skill and care in making any decisions which affected the child or young person’s wellbeing, care and development.[514]

- From 1974 to 1989, the director-general was the administrative head of the Department of Social Welfare,[515] responsible for providing care, protection, education, training[516], [517]

- Where the director-general was the child's or young person’s sole guardian, they were responsible for decisions about where and with whom the child or young person lived.[518]

- Under the Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 the director-general (known as the chief executive from the early 1990s) was responsible for a comprehensive approach to the welfare and protection of children and young persons, considering cultural diversity, preventing child abuse, and maintaining high standards in service provision.[519]

Ngā kaimahi me te whakahaerenga 1950 – 1999

Staff and structure 1950 – 1999

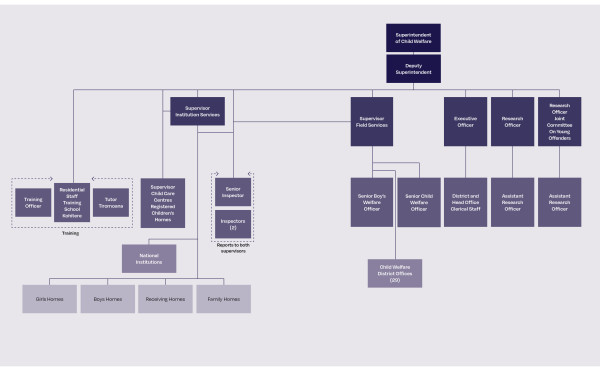

418. The Child Welfare Division was organised into administrative, field, institution and clerical workers. Head office in Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington was responsible for national administration, and included the superintendent, a deputy superintendent, and two supervisors responsible for social welfare facilities and field services (the work of social workers in each district). A senior inspector oversaw the performance of district offices and social welfare facilities. A senior boys’ welfare officer and senior child welfare officer were responsible for staff training and supervision of case work respectively.[520]

419. Field work was carried out by district offices around Aotearoa New Zealand, with each district office under the control of a district child welfare officer. They were responsible, among other things, for boys’ and girls’ homes, receiving homes and Family Homes in their district, as well as the Child Welfare Offices attached to their district.[521] District child welfare officers reported to National Office in Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington, and carried out functions on behalf of the superintendent.[522]

Structure chart for the Child Welfare Division before 1972 [523]

420. While the day-to-day care of children and young people was the responsibility of the residential staff or caregiver, the superintendent, director-general or chief executive relevant to the time was legally responsible for their well-being. They carried out part of that responsibility through delegation to departmental officers and employees such as child welfare officers and social workers.[524]

421. Child welfare officers were supervised in district offices by the district child welfare officer (DCWO).[525] Principals of district facilities reported to the local district director while principals of the four national facilities (Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre, Kingslea Girls' Training Centre, Hokio Beach School and Fareham House) reported directly to the director-general.[526]

422. Under the Child Welfare Act 1925, child welfare officers had broad powers to investigate the circumstances of children and their families, to oversee children under court-ordered supervision, and to inquire into the living situations of illegitimate children and their mothers.[527] A police officer or child welfare officer could apply to the Children’s Court for a warrant to remove children and young people from their home.[528]

423. The superintendent (or any child welfare officer acting with their delegated authority) had the discretion to place a child or young person who was under a court order in any care setting, anywhere in Aotearoa New Zealand, and they could move them at any time.[529] The superintendent or director-general had to personally approve placements for particular settings.[530]

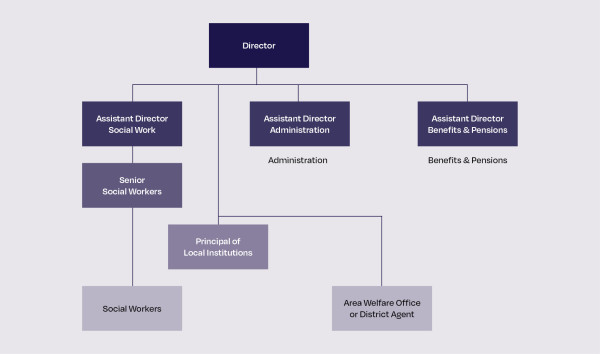

424. By the mid-1980s child welfare officers were known as social workers. Head Office was focused on overall administration of services, planning and advising the government. Directors of Social Work, Residential Services and Institutions and Family Homes reported to the director-general. District offices used a mix of specialist and general social work staff to carry out field work around Aotearoa New Zealand.[531]

Department of Social Welfare District Office Structure 1986 [532]

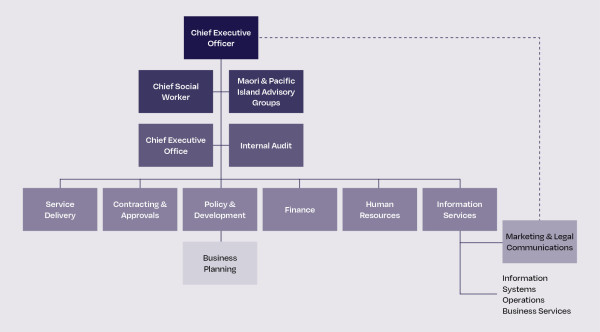

425. In 1992 the Department of Social Welfare was restructured into several different business units, including:

- the New Zealand Children and Young People’s Service, responsible for care and protection, youth justice and adoption services

- the New Zealand Community Funding Agency, responsible for third-party service providers

- the Social Policy Agency, responsible for provision of policy advice and review across core service divisions.[533]

426. The Minister for Social Welfare was responsible for these business units through the Department of Social Welfare as the parent agency.

427. There were further restructures throughout the 1990s, and by 1999 the New Zealand Community Funding Agency had merged with the Children, Young Persons and Their Families to become The Department of Children, Young Persons and Their Families Services (CYPFS). The Department of Social Welfare was disestablished, with CYPFS supported by the Ministry of Social Policy.[534] These restructures would continue past 1999 into the following decades.[535]

The structure of Child Youth and Family as of October 1999 [536]

Te huarahi whakanoho tamariki me ngā rangatahi ki ngā tokoora pāpori

How children and young people were placed in social welfare care

428. The Child Welfare Act 1925 set up a system of Children’s Courts to make decisions for children and young people who came to the attention of the State. Judges in the Children’s Court could deliver a range of judgements for children, bought before the court, for care and protection matters or offences, including placing them in State care. Under the Children and Young Persons Act 1974, the Children and Young Person’s Court heard cases on youth offending, while care and protection matters were heard by the Family Court.[537]

429. Under the Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989, youth justice proceedings were dealt with by a new Youth Court and care and protection proceedings in the Family Court.[538]

430. From 1950 to 1974, the Child Welfare Act 1925 set out four ways children and young people could be committed to social welfare care.

- by agreement: The superintendent could make agreements with a child or young person's parents to take control of them.[539] In such cases, the superintendent held the same powers and responsibilities as if the child were placed under their care through the Child Welfare Act of 1925, excluding guardianship.[540] The superintendent would only assume guardianship if a committal order was issued after a complaint or application to the Children's Court[541]

- by complaint: A constable or child welfare officer could file a complaint with the Children’s Court for children or young people who were neglected, indigent (poor), delinquent, or living in an environment detrimental to their well-being. Children’s Court judges could summon custody holders and issue warrants for the child or young person to be temporarily placed in a social welfare residence such as a borstal or youth prison.[542] Following an investigation a hearing would be held. If the complaint was upheld, the judge could order the child or young person committed to the superintendent or director-general’s care, or supervision by a child welfare officer or social worker.[543]

- by application: A constable or child welfare officer could bypass the complaint and summons process by directly requesting a committal order from the Children’s Court based on a report about the child or young person’s circumstances.[544] If granted, the court didn’t have to specify a facility for the child or young person. Instead, the order gave a constable or child welfare officer authority to take the child or young person to a facility designated by the superintendent, or to the nearest available State institution[545]

- committal following charge: If a child or young person faced charges and appeared before the Children’s Court, the judge could commit them to the care of the superintendent, treating it similarly to a filed complaint.[546] In such cases, the judge did not need to rule on the charges but could base his or her decision to put the child or young person into care on factors such as the child's parentage, environment, history, education, mentality, disposition and other relevant considerations.[547]

431. Under the Children and Young Persons Act 1974, the interests and wellbeing of the child or young person were to be the first and most important consideration of the Court or any other person exercising powers under that Act.[548] In 1983, the Act was amended to provide for a principle in favour of keeping a child or young person with his or her family group, except where expressly required by the Act or impractical.[549]

432. The Children and Young Persons Act 1974 provided for Children's Boards to divert children and young people away from court. Children’s Boards involved community members such as police, social welfare officers, a representative appointed by the Secretary for Māori and Island Affairs, and a local resident.[550] They considered reports and made inquiries to decide on appropriate actions, usually if matters were undisputed by the child or parents.[551] Actions could include counselling or professional help or recommending a complaint to the Children and Young Persons Court by the police or a social worker.[552]

433. From 1982 a complaint could only proceed to the Court after being reported to a Children's Board, except when the Court thought that delay was not in the child's or the public’s best interest.[553]

434. The Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 represented a significant point, both nationally and internationally, in child welfare legislation.[554] It reflected the insights and suggestions outlined in the Puao-te-Ata-Tū Report of 1986, shifting the responsibility for decisions about care and protection for children and young offenders away from the State and toward families and whānau.[555] Beyond outlining general principles, such as prioritising the welfare and interests of the child or young person, the Act also contained specific principles related to care and protection and youth justice matters.[556]

435. At the heart of the Act was the concept of family and whānau decision-making, formalised through the family group conference process.[557] The focus on a child or young person’s whānau, hapū, iwi and extended family was intended to give them more authority and power to make decisions about their children and young people.[558]

436. The Act divided youth justice and care and protection matters, with youth justice proceedings dealt with by a new Youth Court and care and protection proceedings in the Family Court. It emphasised the accountability of young offenders for their actions and the role of families and whānau in supporting them to change their behaviour.[559]

437. While an attempt was made to reduce the powers of the State under the Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989, children and young people could still find themselves being placed into social welfare care if a Court found that they were in need of care and protection or there had been youth offending.

438. For care and protection matters, children and young people would now come to the attention of the State following a report of concern. A report of concern was where a person or an entity told a social worker or the police that they believed a child or young person had been harmed or neglected.[560]

439. Reports of concern could trigger an investigation. If the child or young person was considered to be in need of care or protection, a Care and Protection Coordinator could call a family group conference. The conference addressed concerns and decided recommendations and plans for the child or young person and their family.[561]

440. Care and protection co-ordinators sought consensus on the plan made by the family group conference, and if agreed, the Director-General of Social Welfare was required to implement it unless it was impractical or was inconsistent with the child or young person’s welfare. Financial assistance could be provided if needed.[562]

441. If no agreement was reached, the co-ordinator would report back to the referrer. Referrers, such as social workers or police officers, could then take appropriate actions under the Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989, including the use of warrants or pursuit of custody and guardianship orders in the Family Court.[563]

442. The Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989, like its predecessors, allowed the use of warrants in specific circumstances.[564] Place of safety warrants and warrants to remove a child or young person could be issued if a Judge was satisfied that there were reasonable grounds that a child or young person was suffering, or was likely to suffer, ill-treatment, neglect, deprivation, abuse or harm.[565]

443. The Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 allowed non-government agencies to care for children and young people on behalf of the State. These third-party providers were required to be approved under section 396 of the Act.[566]

444. In 1992 the New Zealand Community Funding Agency (NZCFA) was established within the Department of Social Welfare for the government to purchase social services from the not-for-profit sector. NZCFA inherited roles under the Disabled Persons Community Welfare Act 1975 and the Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 and administered regulations, assessed service providers, negotiated contracts, distributed funds, and monitored performance.

445. The Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 also allowed a parent, guardian or other caregiver to make an agreement with the director-general for the temporary or extended care of a child or young person. This could also include an agreement with an iwi or cultural organisation or the director of a Child and Family Support Service. The maximum length of extended care agreements was usually 12 months. If the child or young person was “so mentally or physically disabled that suitable care for that child or young person can be provided only if that child or young person is placed in institutional care”,[567] the agreement could be for up to two years and could be extended biennially by a family group conference.

446. Under the Care and Protection Handbook (1996–2002), direction was given to social workers that temporary care agreements were only to be entered into when the child or young person would be returning home on expiry of the agreement.

447. The handbook required the social worker to ensure that people entering into the agreement fully understood it and that alternatives, such as accessing support services, were explored. A temporary care agreement could be entered into with one parent, guardian or caregiver in a “crisis situation” but other parents or guardians were to be notified as soon as possible.[568] It also stated that it was “good practice” to consult with a child over the age of 12 years old.[569]

Te wehe i te Taurimatanga Tokoora Pāpori

Exiting Social Welfare Care

448. Until 1961, superintendents decided how long a child or young person stayed in social welfare care. Subsequent Acts introduced changes, allowing requests for discharge from the child, parents, or caregivers.[570] Guardianship under the 1974 Act extended until age 20, subject to the director-general’s discretion.[571] The 1989 Act gave courts the ability to issue declaration orders for custody or guardianship, with specific terms.[572]

449. Social worker manuals from 1957, 1970 and 1984 provided general recommendations for transitioning State wards out of residential care and back into their communities.[573]

450. The key criteria points listed in the 1984 Social Worker Manual included more short-term considerations, like whether a State ward’s living circumstances were satisfactory and whether employment or benefits had been established.[574] There were no points made about ongoing support by the Department of Social Welfare.

Ngā tamariki whaikaha i pāngia e ngā whakaritenga o roto i te ture

Disabled children affected by provisions in the law

451. Similar to the voluntary agreement in Section 142 of the Disabled Persons Community Act 1975, the Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 included separate provisions for the care and protection of disabled children and young people. These provisions applied to those children and young people who were considered to be in need of out of home care due to their disability.[575] Sections 141 and 142 of the 1989 Act enabled out-of-home care placements for disabled children through the Ministry of Health's Disability Support Service. Placement decisions involved the Needs Assessment Service Coordination system, with final approval via a family group conference.

Ngā whakaritenga tokoora pāpori

Social welfare settings

Te taurimatanga i ngā kāinga atawhai me ngā kāinga whānau

Foster and Family Home care

452. Foster care was the most common State care setting for children and young people during the Inquiry period. Children were placed with families – often unrelated to them – to live as a member of that family. Due to the number of foster placements, it is unclear from the records how many such placements occurred, or their locations.

453. Family Homes were established in the mid-1950s as an extension of fostering, with Family Home caregivers intended to be surrogate parents. Married couples ran Family Homes and cared for multiple children. This type of care setting was thought to be more in keeping with a natural family life. Family Homes also allowed siblings to be kept together.[576] By 1972 there were 78 Family Homes around the country.[577]

454. Family Homes were later developed for more transitional placements. However, the continuous shortage of foster carers meant that some children remained in Family Homes for extended periods.

455. In 1983, the Department of Social Welfare and the Department of Māori Affairs started the Mātua Whāngai programme to place tamariki and rangatahi Māori in Māori homes rather than social welfare residences and non-Māori families. Mātua Whāngai evolved into a community-based initiative focused on reintegrating tamariki and rangatahi Māori into their whānau or iwi and ran until around 1991.

Kāinga tokoora

Social welfare residences

456. Social welfare residences were broadly split into national and district institutions, with separate institutions for boys and girls.[578] Each district or major centre had a boys’ and girls’ home for short- to medium-term placements. National institutions existed for long-term placements.[579]

457. There were six national and 14 district facilities which operated from the early 1950s to 1990. There were also receiving homes (or reception centres) which were short-term residences for babies and very young children.[580]

458. Children placed in district institutions were often between placements or being assessed for placement in a foster or Family Home or national institution. Those placed in national institutions were deemed to need an extended period of institutional training and behaviour management.[581]

459. Some residences were large homesteads, usually with several outbuildings, and dormitory-style accommodation. By the mid-1970s, many of the social welfare residences were overcrowded and in poor repair.[582]

460. Over the 1980s the number of these institutions dropped from 26 to four in the main centres (Weymouth, Epuni, Kingslea and Elliot Street).[583]

Whāngai

Adoption

461. Legal adoptions became possible in Aotearoa New Zealand from the late 19th century but remained relatively uncommon before the Second World War. There was a separate legal process for Māori adoptions, which took place through the Native Land Court (the Māori Land Court from 1947). The vast majority of legal adoptions in this era were open, with adoptive children knowing the identity of their biological mother or parents.[584]

462. By 1945 over 1,000 children were adopted annually in Aotearoa New Zealand, growing to 1,880 by 1960.[585] Initially, there were more people wanting to adopt than available children.[586] However, by the early to mid-1960s, State and faith-based institutions were reporting an increase in children being placed up for adoption but extreme difficulties finding adoptive homes.[587]

463. Until 1955 legal adoptions were mainly arranged privately, often by agencies, doctors, maternity homes, hospital matrons or facilitated through faith-based unmarried mothers’ homes.[588] Social workers were not required to approve or be involved in adoptions until the Adoption Act 1955 was passed.[589]

464. The State became more involved in adoptions following the Adoption Act.[590] The Act promoted a ‘complete break’ between birth and adoptive families[591] by providing for closed adoptions by unrelated strangers where “all identifying details of the child’s birth parents remained confidential”.[592] Birth mothers could consent to adoption 10 days following the birth, one of the shortest periods in any country.[593] The birth father’s consent was not required.

465. There were grounds when consent of the parent (almost always the birth mother) or guardian could be dispensed with for adoption to proceed. These were set out in Section 8 of the Adoption Act 1955 and included situations where the parent or guardian had “abandoned, neglected, persistently failed to maintain, or persistently ill-treated the child, or failed to exercise the normal duty and care of parenthood”.[594] It also included situations where the parent or guardian was thought to be unable to care for the child due to physical or mental incapacity.[595]

466. The Child Welfare Division took an active role in identifying the babies of single mothers for adoption, advising its officers to co-operate closely with unmarried mothers’ homes. The Field Officers’ Manual for 1958 to 1969 advised officers to help the mother “think carefully about the future” and “assist her towards a satisfactory decision”.[596] There was a growing reluctance among social workers from the 1960s towards making such intrusive investigations.[597]

467. Between 1984 and 1996, social workers were advised to build a relationship of trust with young mothers while they were still pregnant to help them reach a “realistic decision” that took into regard the child’s future.[598] The Social Work Manual warned that because ex-nuptial pregnancies were now more socially acceptable, and a benefit was available, mothers were “frequently confronted by a tempting choice” of alternatives to adoption:

“Unfortunately experience indicates that many of the young girls who decide to keep their babies are the very ones who are least ready to assume the responsibility – and constraints on their social life – of the care of a young child. The Social Worker should not too readily accept the mother’s statement that she has already decided the baby’s future.”[599]

468. Adoption rates peaked at 3,976 in 1971, comprising 6 percent of live births, and declined to 2,200 by 1979 (4 percent of live births).[600] Most adoptions involved children born to unmarried parents,[601] with a decrease in the percentage over the years (82 percent in 1945, 67 percent in 1971). Even into the 1970s, when social attitudes towards single motherhood began to shift, State financial support remained limited. Few childcare options existed, and women's work was often low paid. This severely constrained single mothers’ ability to provide for themselves and their children.[602] An estimated 45,000 closed stranger adoptions occurred between 1955 and 1985.[603]

469. In 1985 the Adult Adoption Information Act 1985 allowed adopted people aged over 20 to obtain their original birth certificate and potentially apply for identifying information about their birth mother and / or father.[604]

Table of legal adoptions during the period of 1943 – 1979 [605]

1943 |

1944 |

1945 |

1955 |

1960 |

1965 |

1970 |

1971 |

1972 |

1974 |

1979 |

|

|

Total Adoptions |

577 |

1,313 |

1,191 |

1,455 |

1,880 |

3,088 |

3,837 |

3,976 |

3,642 |

3,366 |

2,200 |

|

Adoptions as % of live births |

1.9% |

3.91% |

3.22% |

2.92% |

3.39% |

5.14% |

6.18% |

6.17% |

5.75% |

5.67% |

4.21% |

|

Adoptions known to Child Welfare Divisions/DSW |

Not available |

1,065 |

1,151 |

1,366 |

1,796 |

2,835 |

3,362 |

3,231 |

3,280 |

3,366 |

2,200 |

|

Adoptions involving ex‑nuptial births |

Not available |

903 |

973 |

1,062 |

1,377 |

2,429 |

2,831 |

2,674 |

2,713 |

1,821 |

845 |

|

Adoptions by strangers |

Not available |

Not available |

Not available |

Not available |

984 |

1,327 |

2,162 |

2,176 |

2,136 |

1,821 |

845 |

|

Adoptions of children under 1 year old |

Not available |

Not available |

Not available |

Not available |

849 |

1,321 |

2,503 |

2,969 |

2,892 |

2,474 |

1,258 |

Te Ture Whāngai 1955, te whāngai Māori me te whāngai

The Adoption Act 1955 and Māori whāngai and adoptions

470. Māori traditionally had a system of caring for children among wider whānau and had common and accepted practices such as whāngai or atawhai, which involved tamariki Māori being raised by whānau members.[606] Whāngai also enabled tamariki Māori to maintain connection with their birth whānau and their whāngai whānau and meant the child’s and hapū rights and privileges remained protected.[607]

471. From the 1900s Māori adoptions and whāngai became increasingly controlled and regulated by the State. In 1901, Māori adoptions and whāngai were not recognised legally unless they were registered in the Native Land Court, where they had to be approved by a judge.[608] In 1909, it became illegal for Māori to adopt non-Māori. Māori rates of adoption and whāngai were not recorded during this time.

472. The 1955 Act removed the ban on Māori adopting non-Māori, and Māori adoptions were also brought under almost the same rules as adoption. As such, the Act did not recognise Māori whāngai practices.[609]

473. A 1962 amendment transferred Māori adoption hearings from the (open) Māori Land Courts to the (closed) Magistrates Courts. Financial costs and questioning of applicants’ personal circumstances disadvantaged whānau Māori.[610] This reduced the number of potential Māori adoptive parents and increased the likelihood of pēpē and tamariki Māori being placed in foster care or being adopted by Pākehā parents.[611]

474. Some pēpē and tamariki Māori adopted out through this closed process lost knowledge of their whakapapa or were even unaware that they were Māori.[612] For tamariki Māori who were adopted out, their iwi were rarely recorded, and their ethnicity was often incorrectly recorded.

475. This was particularly the case where the mother was Pākehā and the father was Māori. Pākehā women increasingly gave their pēpē up for adoption to avoid racial and social discrimination and prejudice, often omitting the name of the Māori fathers on birth certificates.[613] Dr Anne Else told the Inquiry that any claims from the father or wider whānau were often not recognised:

“This aspect of the law proved highly significant in cases where the birth mother was Pākehā and the father was of Māori heritage. Māori social workers recalled many cases where the birth father’s family, especially the grandparents, wanted to adopt the child, but had no standing and were not permitted to do so.”[614]

476. Māori researchers and experts have noted closed adoption policies were part of a wider context of State policies “oriented towards the nuclear family, domesticity and producing ‘ideal citizens’”, and supported the prevailing assimilationist agenda.[615]

Whakaritenga whakawhiti, whakaū ture hoki

Transitional and law enforcement settings

477. NZ Police also had children, young people and adults in their care. Children, young people and adults in care for disability or mental distress who were picked up by police officers or were being processed for sentencing or placement in another care setting could find themselves temporarily in police cells, police custody, court cells and transfers to, between, or out of State care residences. Police cells were also used sometimes when there were no beds available in other facilities.[616]

478. Police cells were established as penal institutions under the Penal Institution Act 1954 for holding a person on remand or for short-term sentences.[617] Under the Criminal Justice Act 1954, young people could be sentenced to imprisonment in an adult prison if the judge thought it was appropriate.[618]

479. The role of NZ Police in relation to care was often carried out alongside social workers. Children and young people came to the attention of police officers for a variety of reasons, from perceived antisocial behaviour to notifications and referrals from other agencies.

480. The Child and Young Persons Act 1974 detailed the broad powers of police officers to pick up unaccompanied children in public places if they were in an environment ‘which is detrimental to his physical or moral well-being'.[619] Police officers ultimately had discretion to determine whether a situation was harmful to the child or young person’s well-being. If a parent or guardian could not be found, police officers could deliver the child or young person to the custody of the Director-General of Social Welfare.[620]

481. The Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 outlined principles for dealing with young offenders, emphasising that criminal proceedings should be a last resort,[621] not initiated solely for welfare assistance, and designed to strengthen the family group’s ability to address offences.[622] Police officers had to consider alternatives such as warnings or formal cautions, with recommendations from family group conferences.[623]

482. Family group conferences offered an opportunity for families to respond to issues involving their young people before matters reached the courts.[624] From the 1990s, family group conferences became the primary means of dealing with young offenders. Of nearly 6,000 family group conferences held in 1990 / 1991, only 300 cases were referred on to the Youth Court for resolution.[625]

483. Police officers could arrest a child or young person without a warrant for purely indictable (requiring a prison term) offences in the public interest or in specific situations.[626] After arrest, with their agreement, the child or young person could be delivered to an iwi or cultural authority, the director-general, or placed in custody, depending on the circumstances.[627] This could also be done without their agreement, but had to happen within 24 hours[628] unless a senior social worker and member of the police agreed the child or young person was likely to run away or be violent and social welfare did not have suitable facilities for them.[629] In these circumstances, the young person could be detained in police custody until appearing in Court.[630]

Te manatika taiohi

Youth justice

484. From the 1950s to the late 1990s, Aotearoa New Zealand had several types of settings for young people considered to be in need of youth justice care or corrective training. These included borstals, detention centres and youth prisons. Some social welfare residences also had a corrective or training element to them intended to address perceived behavioural issues with children and young people – this included residences such as Hokio, Kohitere and Epuni.

485. Up until 1995 when the Department of Corrections was formed, the Department of Justice was responsible for overseeing young people in these facilities.[631] If the Department of Social Welfare was transferring a young person from a social welfare residence to a borstal, they were no longer responsible for the young person once the transfer was complete.[632]

486. Borstals were introduced in 1924 with the Prevention of Crime (Borstal Institutions Establishment) Act 1924. Young offenders between 15 and 21 years of age[633] could be sentenced to undergo borstal training for a period of up to three years[634] if they had been convicted of an offence punishable by imprisonment.[635]

487. The purpose of the borstals was to reform young offenders with the goal of diverting them from becoming habitual criminals.[636] A 1969 review of Aotearoa New Zealand Borstals stated that borstals aimed to:

- “keep youths from further offending during a difficult period of their lives

- “develop moral standards, good work habits, vocational skills, and personal hygiene"

- “train youths to live responsibly as citizens in the community.”[637]

488. As their sentence progressed, borstal trainees were gradually awarded privileges, freedoms and responsibilities during their stay to rehabilitate them for life on the outside.[638] However, borstal trainees often had a high rate of reoffending.[639]

489. There was also the option to send young people that had been convicted of an offence punishable by imprisonment to a detention centre for short-term corrective training. At the beginning of the Inquiry period young people between the age of 17 and 23 years could be sent to a detention centre for corrective training for a period of four months.[640] In 1961 the age range was lowered to between 16 and 21 and the length of the programme was reduced to three months.[641]

490. Borstals and detention centres were abolished by the Criminal Justice Amendment Act 1975, though this did not come into force until 1981.[642] Though the borstal programme was finished, under the Penal Institutions Amendment Act 1980, some borstals transitioned into youth prisons and became known as Youth Institutions from April 1981.[643]

491. Under the Criminal Justice Act 1954, young people could also be sentenced to imprisonment in an adult prison, if the judge believed that it was appropriate.[644] Children and young people were sometimes held in adult prisons on remand or awaiting court when other facilities were full.[645]

492. There was one borstal for girls, Arohata, which was attached to the women’s prison in Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington. It opened in 1944 and closed in 1981. There were five borstals for boys, two in the South Island – Waihōpai Invercargill and Waipiata – and three in the North Island, at Kaitoke, Tongariro and Waikeria. All were closed by 1981.

493. There were also four detention centres, the first of which opened in Waikeria in 1961. The other three were Rangipo and Hautu, both near Tūrangi, and Rolleston in Waitaha Canterbury. By the late 1980s these had also closed.

494. The Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 established mixed purpose residences with both youth justice and care and protection, although the two groups were generally cared for separately.

495. Some of the former social welfare residences were adapted to these new mixed purpose residences. These included Kingslea Residential Centre in Ōtautahi Christchurch, Puketai in Ōtepoti Dunedin, Epuni in Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington, Dey Street in Kirikiriroa Hamilton and Northern Residential Centre in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland (formerly Weymouth). From the mid-1990s there was concern about the mixing of care and protection and youth justice groups[646] and a youth justice-only facility was opened in Te Papaioea Palmerston North in 1997.

496. From the 1990s children and young people charged through the courts could also be sent to third-party providers contracted under section 396 of the Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989. The main ones which took young offenders in the 1990s were Moerangi Treks in Te Urewera and Whakapakari on Aotea Great Barrier Island. From 1999 the State also funded a residence in Ōtautahi Christchurch, managed by Barnados, for adolescent sex offenders.

Te whaikahatanga me te whaioratanga

Disability and Mental Health

I te Tari Hauora me ngā poari hohipera te haepapa matua

Department of Health and Hospital Boards had overall responsibility

497. Decisions about how the disability and mental health care system operated were usually made at a national level by the Minister of Health, the Director-General of Health or the Department of Health.[647]

498. Ultimate accountability for the disability and mental health care system sat with the Minister of Health, who provided overall direction, oversight and control over the system.[648]

499. During the Inquiry period decisions about what disability and mental health care should look like and how it should be delivered and funded sat variously with the Department of Health (followed by the Ministry of Health from 1993 onwards) and Division of Mental Health / Mental Hygiene, the Director-General of Health and the Director of Mental Hygiene / Mental Health, and a range of devolved decision-makers including Area Health Boards and Crown Health Enterprises.[649]

500. The Director-General of Health was the chief administrative officer of the department, and the Ministry of Health from 1993. Reporting to the Director-General was the Director of Mental Hygiene, later Director of Mental Health, who had specific legislative obligations relating to people in disability and mental health care.[650]

501. Until 1983, hospital services were provided by District Health Offices and Hospital Boards. From 1983 to 1993 there was a decentralisation of purchasing and provision of health care away from the Department of Health to Area Health Boards, and with further reform this changed again to Regional Health Authorities and Crown Health Enterprises and the establishment of Needs Assessment and Service Coordination agencies. In 1998, further reform created the Health Funding Authority and Hospital and Health Services.[651]

502. More localised decisions about how specific institutions or third-party providers should be run were made by individuals such as superintendents or medical officers, or devolved decision-makers such as Area Health Boards and Crown Health Enterprises.

503. In 1992 the Needs Assessment and Service Coordination system was set up after a review of the existing disability support services.[652] The funding and delivery of existing support services were redistributed across the four Regional Health Authorities.[653]

504. Under this system, disabled people needed to be assessed to see what funding they were eligible for. This funding then determined the support and resources they could access.[654]

Ngā ngaio hauora me ētahi atu kaimahi taurima

Health professionals and other care workers

505. Most immediate to people in health settings were medical professionals and other health care workers who made decisions about individual treatment, care and other daily activities. Decision-making about how care and treatment was provided both generally and in specific instances by medical professionals and health care workers, including doctors, psychiatrists, nurses and other health care workers.

Ngā ture mō te whaikaha me te hauora hinengaro

Disability and mental health legislation

506. The Mental Defectives Act 1911 set out the conditions for admission into disability and mental health institutions until it was replaced by the Mental Health Act 1969. The Mental Defectives Act 1911 was the first legislation in Aotearoa New Zealand to categorise types of disability, long-term health conditions and mental distress. The Act arranged ‘mental defectives’ into six categories: persons of unsound mind, mentally infirm, idiots, imbeciles, feeble-minded and epileptics. [655]

507. This was extended by the Mental Defectives Amendment Act 1928 to include a seventh category: persons socially defective (defined as anti-social behaviour requiring supervision).[656]

508. The Mental Health Act 1969 replaced the Mental Health Act 1911 and its amendments but continued the same basic approach. Under the Mental Health Act 1969 anyone who met the definition of ‘mentally disordered’ in the Act, including those suffering from mental illness or deemed ‘mentally infirm’ or ‘mentally subnormal’ could be required to undergo treatment through a compulsory treatment order.[657] The 1969 Act was replaced by the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992.

Whare hauora hinengaro

Psychiatric hospitals

509. For people who experienced mental distress during the Inquiry period, placement in psychiatric settings was often compulsory. It was not until the enactment of the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992 that the focus shifted to upholding the rights of those under compulsory treatment.

510. People who experienced mental distress were placed in psychiatric settings by order of the court, on an emergency basis, or through the criminal justice system. Sometimes people entered mental health settings voluntarily or on the advice of their family or clinician.[658]

511. The Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992 led to substantial changes in New Zealand’s mental health system. It put more importance on the rights of patients, recognising the role of cultural factors in diagnosis and treatment and the right to appeal treatment.[659]

512. The 1992 Act still enabled compulsory mental health assessment or treatment, if someone was judged to be a serious danger to themselves or others, or unable to take care of themselves.[660] People experiencing mental distress could also be compulsorily assessed and treated in the community.

513. The Director of Mental Health became responsible for administration of the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992.[661] The Director-General of Health could also appoint a director of area mental health services for each region, to lead the mental health workforce for their area.[662]

514. By 1911, Aotearoa New Zealand had six asylums – Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, Porirua, Whakatū Nelson, Sunnyside (Waitaha Canterbury), Seaview (South Island West Coast) and Seacliff (Ōtepoti Dunedin) – with a combined total of 3,913 patients.[663] As the 20th century progressed, these buildings were replaced by villa-type residences, usually located in more rural areas.[664]

515. Psychiatric settings continued to grow as Kingseat (Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland), Tokanui (Te Awamutu), Cherry Farm (Ōtepoti Dunedin) and various inpatient units attached to hospitals were established. By 1996, almost all the large psychiatric hospitals had closed.[665]

Whare hauora hinengaro tamariki

Psychopaedic hospitals

516. Psychopaedic was a 20th century Aotearoa New Zealand term to distinguish children, young people and adults with a learning disability from people who experienced mental distress. The main psychopaedic institutions were Templeton (Waitaha Canterbury), Kimberley (Taitoko Levin), Braemar (Whakatū Nelson) and Mangere (Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland).[666] Some psychiatric hospitals such as Tokanui had psychopaedic wards.

517. Families could voluntarily place their disabled family member into one of these hospitals, often because a lack of other supports in the community meant they had no other real options. Authorities such as medical staff often recommended psychopaedic care as the best choice.

518. The large institutions began to close in the 1990s and were replaced with smaller group residential homes. These were mainly run by voluntary organisations contracted by the State, such as the IHC and trusts.[667]

Kāinga mō te hunga whaikaha ā-tinana

Homes for physically disabled people

519. For disabled people with no family support, limited care options existed until the establishment of some group homes in the early 20th century. In 1914, the Elizabeth Knox Home and Hospital opened in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, with the specific purpose of caring for disabled people with physical impairments.[668]

520. Pukeora, an institution for children and young adults with physical impairments, was founded near Dannevirke in the late 1950s.[669]

Wāhi mahi āhuru

Sheltered workshops

521. From the early part of the 20th century, sheltered workshops provided employment and training for wounded war veterans, or disabled civilians with learning or physical impairments.[670] The work was menial and repetitive, and payment was tokenistic. However, the workshops became the main source of occupation for many disabled people.

522. In 1956, the responsibility for the Occupational Centres, originally founded by the Intellectually Handicapped Children’s Parents Association, was transferred to the control of regional Education Boards. These centres became Day Special Schools under the management of the State. Children who had attended day programmes run by voluntary groups could transfer to the special schools. Government funding was provided to the IHC Occupation Workshops catering for the needs of adults with learning disability.[671]

523. Disabled people who worked in sheltered workshops were not given the same rights as other employees and were exempt from legislation designed to protect employees throughout the Inquiry period.[672]

Hōpuni hauora

Health camps

524. Health camps were established in the early 20th century and focused on physical health and nutrition for children and young people, such as recovering from tuberculosis, or to put on weight or increase fitness and learn healthy habits.[673] Responsibility for health camps was shared between the Department of Health and the Department of Education.[674] Health camps were administered by a board and had their own legislation – the King George V Memorial Fund Act 1938 and the Children’s Health Camp Act 1972.[675]

525. From the 1960s onwards, the focus turned to children with emotional or behavioural difficulties. Health camps provided respite care, particularly those with difficult home lives. This was in line with the better understanding of children and child psychology emerging at the time.

526. By the 1950s, permanent health camps had been established in Whangarei, Pakuranga, Tairāwhiti Gisborne, Ōtaki, Whakatū Nelson, Ōtautahi Christchurch (Glenelg) and Roxburgh (Ōtākou Otago). Children were referred to them through school nurses, teachers or their family doctor.[676]

527. By the 1980s all the camps were still in use, other than the camp at Whakatū Nelson. In 1983 the Princess of Wales Children’s Health Camp was opened in Rotorua. In the late 1990s some of these health camps began to close. In 1999 responsibility for remaining health camps and their liabilities was transferred to a charitable trust, Stand Tu Māia.[677]

Mātauranga

Education

Te Ture Mātauranga me Te Tari Mātauranga

Education legislation and the Department of Education

528. Up until 1989, the Director-General of Education oversaw the administration of the education sector under the Education Acts 1877, 1914 and 1964, along with their amendments and regulations. The Department of Education had regional offices in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington, and Ōtautahi Christchurch, each under the control of a superintendent.[678]

529. The Department inspected all schools (State, State integrated and private), organised the recruitment, training and assessment of teachers, and directly controlled departmental special schools, the Correspondence School, and the Psychological Service (a diagnostic, advisory, and counselling service for children whose academic or social progress was causing concern).[679]

530. Ten regional education boards were responsible for the control and management of State primary schools. Each primary school also had a school committee whose main responsibilities were the maintenance of school buildings, grounds and equipment.[680]

531. State secondary schools were administered by boards of governors (made up of representatives of parents, members of the education board of the district, representatives of other local organisations, and a teacher), which was responsible for the management of the school, including the appointment of the principal and staff.[681]

532. The Education Act 1989 saw a major change in the education sector with the Tomorrow’s Schools reforms. These reforms changed the way schools and kura were governed. Decision-making moved away from central government agencies to school communities via self-managing and self-governing locally elected school boards of trustees. The Department of Education was abolished by the Education Act 1989 and replaced by the smaller Ministry of Education.

533. The Education Act 1989 brought in powers to allow the Secretary for Education to intervene in the control and management of schools in trouble, including in some circumstances dissolving the Board and appointing a Commissioner in its place.[682] From 1990 the Secretary of Education had powers of entry and inspection of all registered schools. From 1998 they also had powers to enter private schools suspected of operating while unregistered.[683]

Kura kōhure

Special schools

534. Before 1950 the government had established a number of State special schools, units and classrooms for children and young people who were Deaf, blind, had additional learning needs, or had “behavioural management challenges”.[684] During the Inquiry period there were five residential special schools overseen by the Department of Education, as well as schools for Deaf, blind and Deafblind students.

535. The first two special schools, Salisbury and Campbell Park, were opened in the 1900s. Campbell Park was located near Oamaru and had a maximum roll of 108. It was for boys aged 10 to 17 years old who were considered emotionally disturbed, ‘backward’ or aggressive.[685]

536. Salisbury School in Whakatū Nelson could take up to 90 girls aged 8 to 18 years old who were seen as “educationally backward, delinquent or had personal or social problems.”[686] Campbell Park and Salisbury took referrals through the Department of Education’s psychological service or the Child Welfare Division.

537. Mount Wellington Residential School for Maladjusted Children opened in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland in 1960, before moving to Bucklands Beach in 1980, when it was renamed Waimokoia. It was intended to cater for children with severe behavioural and social problems.[687]

538. McKenzie Residential School opened in Ōtautahi Christchurch in 1971 for children with serious emotional difficulties.[688] It could take up to 25 children from the ages of 7 to 14 years old.[689]

539. Several schools were established for Deaf or blind children and young people.

- Sumner Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, which opened in 1880 (then Van Asch College, combined with Kelston to become Ko Taku Reo: Deaf Education New Zealand in 2020)

- Kelston School for the Deaf, which opened in 1958

- Jubilee Institute, which opened in 1890 and offered the first educational services for blind children in Aotearoa New Zealand, as well as a residential programme and workshops for blind adults.[690] It was opened by the Royal New Zealand Foundation for the Blind at Parnell[691]

- Homai School for the Blind replaced Jubilee Institute for the Blind of New Zealand, opening in 1965. A facility for Deafblind students was added in 1968.

540. Children could be admitted to schools for the Deaf as day pupils at the age of 3 years old and boarding pupils at 5 years old.[692]

541. Under the Education Act 1964 the minister could establish “any special class, clinic or service” and outline conditions for compulsory enrolment of certain children.[693] For disabled children the Act provided alternative education pathways where a regular school may not have provided a suitable education to meet their needs. The Act provided for training teachers for special education purposes and regulations regarding funding and inspections.[694] The Education Department employed educational psychologists, while regional Education Boards employed speech language therapists, to assist children with special education needs who were enrolled in regular schools. [695]

542. The Department of Education was responsible for the education of all children, including disabled children in psychopaedic and psychiatric institutions. However only a small proportion of children in these settings went to a school and received an education. The Department of Health trained and employed training officers in institutions that provided a minimal level of education to children, often focused on behaviour modification using aversion techniques, known during the Inquiry period as aversion therapy.[696]

543. The growing trend towards mainstreaming the education of learning-disabled children led the rolls of the Department of Education’s special residential schools to shrink over the 1980s.

544. Falling rolls led to some school closures. Campbell Park closed in 1987, and its remaining pupils were transferred to Hogben School (formerly Marylands) or placed into mainstream schools with learning support.

545. The Education Act 1989 formalised the move away from special residential schools to the State education system by increasing provisions for disabled children in mainstream education.

546. The Act signalled a move away from the previous model of segregation in residential institutions towards an inclusive educational environment that aimed to integrate the needs of all students. However, the Secretary of Education could still direct a disabled child to attend a special school or class.

Te Ratonga Hauora Hinengaro

The Psychological Service

547. Established in 1945, the Department of Education’s Psychological Service was the main assessment and guidance service available to assist children from birth to their late adolescent years, their parents and their teachers. Schools, parents, child welfare officers, doctors, and government and voluntary agencies could refer children and young people to the service for assessment and advice.[697] After 1989 a new crown entity, the Special Education Service, was created to provide specialist support and interventions to students with special educational needs.

He hononga tō ngā kura ki te tokoora pāpori me ngā kāinga tika rangatahi

Schools attached to child welfare and youth justice residences

548. Many social welfare and youth justice residences had schools onsite, with teachers supplied by the Department of Education. After 1989 these onsite schools were staffed by either staff supplied by the Ministry of Education, or third-party providers contracted to provide education services.[698] They were classified as special schools and provided a mix of primary and secondary education depending on the age mix at the social welfare residence they were attached to.[699] Social welfare staff at the residences were expected to work collaboratively with the onsite teachers to support student learning.[700]

Te Tari Arotake Mātauranga

Education Review Office

549. The Education Review Office (ERO) was established in 1989 as part of the Tomorrow’s Schools reforms. ERO is a government department with responsibility for evaluating and publicly reporting on the education and care of children and young people in early childhood services and schools. The majority of its reviews are regular, although on occasion ERO will complete a review on a particular matter of concern or as directed by the Minister of Education. [701]

Te Poari Rēhita Kaiako

Teacher Registration Board

550. Before 1989, teachers in State schools were required to be registered and the Teacher’s Register was kept by the Director-General of Education.[702]

551. The Teacher Registration Board was established by the Education Act 1989.[703] The Registration Board was established with no functions specified in legislation.

552. The mandate of the Registration Board was to register and certify teachers. The Registration Board could consider cancellation of registration on the grounds of character, fitness to teach or lack of satisfactory training.[704]

Kura Hourua

State integrated schools

553. Prior to the Private Schools Conditional Integration Act 1975, all faith-based schools were private. The Act came into effect in August 1976 and provided the option for private schools to integrate into the State education system. They could then receive government funding and had to teach the New Zealand Curriculum, while being able to maintain their religious or “special character” and offer religious education.[705]

Kura tūmataiti

Private schools

554. In 1975, ahead of the Private Schools Conditional Integration Act, around 11 percent of primary and 18 percent of secondary students attended private schools in Aotearoa New Zealand.[706] As discussed in the section on faith-based schools, the number of private schools decreased after integration became an option in 1976.

555. Private schools are both owned and operated by private entities rather than the State. Private schools must follow the law in running the school. They receive some State funding and must be registered, but otherwise have a large amount of flexibility in setting their own curriculum, assessment methods and internal rules.[707]

Kura Noho

Boarding schools

556. By 1997 Aotearoa New Zealand had 102 schools with some form of boarding facility available. Seventy-eight of these were State or State integrated, and 24 were private schools. Most were single sex, for boys or girls only. Around 3 percent of all students attending State and State integrated schools and 16 percent of those attending private schools boarded in hostels connected to those schools.[708] Most boarding schools also had pupils who attended as day students and did not live in boarding hostels during term time.[709] The term boarding school was not legally defined but covered a variety of arrangements for student education and accommodation.[710]

557. Responsibility for boarding hostels in State and State integrated schools varied between boards of trustees / school boards, boards of proprietors, hostel trust boards, private companies, hostel committees and, where a hostel was used by more than one school, trusts made up of appointees from parents, trust boards and the schools concerned. In private schools the hostel was governed by the school trust board.[711] Hostels might be on the same physical site as the school, or in another location.[712] The Education Act 1989 was largely silent about school hostels and the responsibilities of Boards of Trustees for student safety in hostel accommodation.[713] Hostel accommodation was essentially a private commercial arrangement between parents and the hostel management.[714]

Footnotes

[502] Children and Young Persons Amendment Act 1983, sections 4A, 4B and 4C.

[503] Child Welfare Act 1925.

[504] Frater, M, Why and how children went into care: a legal analysis of the legislative framework for care: Background paper for the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (2019, page 29).

[505] Frater, M, Why and how children went into care: a legal analysis of the legislative framework for care: Background paper for the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (2019, page 29).

[506] Parker, W, Social Welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume I: National policies and procedures (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, page 9).

[507] Department of Education, Child Welfare Division Field Officers’ Manual, part 1, chapter 2 (1953, page 4).

[508] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 3; Department of Education, Child Welfare Division Field Officers’ Manual, part 1, chapter 2 (1953, page 4); The Infants Act 1908 was repealed in 1989.

[509] Parker, W, Social Welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume I: National policies and procedures (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, page 9).

[510] Parker, W, Social Welfare residential care 1950-1994, Volume I: National policies and procedures (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, page 9).

[511] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 12(1).

[512] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 13(4).

[513] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 16.

[514] Earl White v Attorney General, HC, Wellington, CIV-2001-485-864 (28 November 2007, para 346).

[515] Department of Social Welfare Act 1971, section 6.

[516] Children and Young Persons Act 1974, section 49(4).

[517] Children and Young Persons Act 1974, section 5(1).

[518] Earl White v Attorney General, HC, Wellington, CIV-2001-485-864 (28 November 2007, para 346).

[519] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989, section 7.

[520] Department of Education, Child Welfare Division Field Officers’ Manual, part 1 (1953, page 104).

[521] Department of Education, Child Welfare Division Field Officers’ Manual, part 1 (1953, page 106).

[522] Department of Education, Child Welfare Division Field Officers’ Manual, part 1 (1953, page 106); Ministry of Social Development, Record keeping history of the Ministry of Social Development and its predecessor agencies: Part One agency structure, records systems and procedures (n.d., page 37).

[523] Ministry of Social Development, Record keeping history of the Ministry of Social Development and its predecessor agencies: Part One agency structure, records systems and procedures (n.d., page 46).

[524] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 6(1).

[525] Parker, W, Social Welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume I: National policies and procedures (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, page 11).

[526] Department of Education, Child Welfare Division Field Officers’ Manual, part 1 (1953, page 106).

[527] Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 1998, page 97); Parker, W, Social Welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume I: National policies and procedures (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, page 9).

[528] Child Welfare Act 1925, (No 22), section 13 (2).

[529] Child Welfare Act 1925, sections 13 (9) and 20(1), (Repealed); Children and Young Persons Act 1974, section 49(4); Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989, sections 105 and 362.

[530] Department of Social Welfare, Social Workers Manual (1984, page 47); Department of Social Welfare, Social Workers Manual (1985, page 83); Department of Social Welfare, Social Workers Manual (1989, page 81).[531] Sagar, M, Psychologists and the Department of Social Welfare (publisher unknown, 1986, pages 2–3).

[532] Sagar, M, Psychologists and the Department of Social Welfare (publisher unknown, 1986, page 3).

[533] Ministry of Social Development, Record keeping history of the Ministry of Social Development and its predecessor agencies: Part One agency structure, records systems and procedures (n.d., pages 125–126).

[534] Ministry of Social Development, Record keeping history of the Ministry of Social Development and its predecessor agencies: Part One agency structure, records systems and procedures (n.d., pages 125–156).

[535] Garlick, T, Social developments: An organisational history of the Ministry of Social Development and its predecessors, 1860–2011 (Steele Roberts Aotearoa, 2012, pages 278 and 283–286).

[536] Ministry of Social Development, Record keeping history of the Ministry of Social Development and its predecessor agencies: Part One agency structure, records systems and procedures (n.d., page 157).

[537] Garlick, T, Social developments: An organisational history of the Ministry of Social Development and its predecessors, 1860–2011 (Steele Roberts Aotearoa, 2012, pages 53 and 93).

[538] Garlick, T, Social developments: An organisational history of the Ministry of Social Development and its predecessors, 1860–2011 (Steele Roberts Aotearoa, 2012, page 132).

[539] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 12(1).

[540] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 12(2).

[541] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 12(2).

[542] Child Welfare Act 1925, sections 13(1) and 13(2).

[543] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 13(4).

[544] Child Welfare Act 1925, sections 13(5), 13(7).

[545] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 13(6).

[546] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 13(5).

[547] Child Welfare Act 1925, section 31.

[548] Children and Young Persons Act 1974, section 4.

[549] As inserted by the Children and Young Persons Amendment Act 1977 (No 126), section 3.

[550] Children and Young Persons Act 1974 (No 72), section 13.

[551] Children and Young Persons Act 1974 (No 72), section 15(8).

[552] Children and Young Persons Act 1974 (No 72), section 15(7).

[553] As inserted by the Children and Young Persons Amendment Act 1977 (No 126), section 7.

[554] Transcript of evidence of Chief Ombudsman Peter Boshier (26 August 2022, pages 1041–1042).

[555] Frater, M, Why and how children went into care: a legal analysis of the legislative framework for care: background paper for the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (2019, page 29).

[556] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989, sections 5 and 13.

[557] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989, sections 20–38.

[558] Frater, M, Why and how children went into care: a legal analysis of the legislative framework for care: background paper for the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (2019, page 29).

[559] Watt, E, A history of youth justice in New Zealand, research paper commissioned by the Principal Youth Court Judge (2003, pages 24–26); Children, Young Persons, and their Families Act 1989 (No 24), section 208.

[560] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), section 15.

[561] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), sections 18(1) and 19(3).

[562] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), sections 30 and 34.

[563] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), sections 31 and 31(2).

[564] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), sections 39–40.

[565] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), sections 39–40.

[566] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), section 396.

[567] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), section 141.

[568] Child Youth and Family Care and Protection Handbook, 1996-2002, (Version 2.1, June 2000). 10-6.

[569] Child Youth and Family Care and Protection Handbook, 1996-2002, (Version 2.1, June 2000). 10-7.

[570] Child Welfare Act 1925 (No 22), section 23.

[571] Either married, or was adopted other than by a parent (Children and Young Persons Act 1974, No 72, section 49(7)).

[572] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989, sections 101(1) and (2); Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), section 110(1)(a)-(e).

[573] Department of Education, Child Welfare Division Field Officers’ Manual (1957, section J.468); Department of Education, Child Welfare Division Social Workers’ Manual (1970, section J27); Department of Social Welfare, Social Work Manual, Volume 2 (1984, section N21).

[574] Department of Social Welfare, Social Work Manual, Volume 2 (1984, section N21.3).

[575] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), section 141.

[576] Craig, T & Mills, M, Care and control: The role of institutions in New Zealand (New Zealand Planning Council, 1987, page 36).

[577] Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 1998, page 173).

[578] Parker, W, Social Welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume. I: National policies and procedures (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, page 10).

[579] Parker, W, Social Welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume I: National policies and procedures (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, page 51).

[580] Parker, W, Social Welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume. I: National policies and procedures (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, pages 50–51); Garlick, T, Social developments: An organisational history of the Ministry of Social Development and its predecessors, 1860–2011 (Steele Roberts Aotearoa, 2012, page 133).

[581] Parker, W, Social Welfare residential care 1950–1994, Volume I: National policies and procedures (Ministry of Social Development, 2006, page 51).

[582] Carson, R, New horizons: A review of the residential services of the Department of Social Welfare (Department of Social Welfare, 1982, page 59).

[583] Garlick, T, Social developments: An organisational history of the Ministry of Social Development and its predecessors, 1860–2011 (Steele Roberts Aotearoa, 2012, page 133); Savage, C, Moyle, P, Kus-Harbord, L, Ahuriri-Driscoll, A, Hynds, A, Paipa, K, Leonard, G, Maraki, J, & Leonard, J, Hāhā-uri, hāhā-tea: Māori involvement in State care 1950–1999 (Ihi Research, 2021, page 92).

[584] Else, A, A question of adoption: Closed stranger adoption in New Zealand, 1944–1974 (Bridget Williams Books, 1991, pages x–xi, page 24).

[585] Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 1998, page 224).

[586] Else, A, A question of adoption: Closed stranger adoption in New Zealand, 1944–1974 (Bridget Williams Books, 1991, page 48); Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 1998, page 233).

[587] Else, A, A question of adoption: Closed stranger adoption in New Zealand, 1944–1974 (Bridget Williams Books, 1991, paras 67–69).

[588] Witness statement of Dr Anne Else (9 October 2019, page 4).

[589] Else, A, Adoption: Growth in adoption (Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 2011, page 2), https://teara.govt.nz/en/adoption/page-2.

[590] Adoption Act 1955.

[591] Witness statement of Dr Anne Else (9 October 2019, page 5).

[592] Haenga-Collins, M, Closed stranger adoption, Māori and race relations in Aotearoa New Zealand, 1955–1985, Doctoral Thesis, Australian National University (March 2017, page 1).

[593] Witness statement of Dr Anne Else (9 October 2019, page 5).

[594] Adoption Act 1955, section 8(1).

[595] Adoption Act 1955, section 8(2).

[596] Department of Education, Child Welfare Division Field Officers Manual (c. 1958-1969, I.289).

[597] Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 1998, page 264).

[598] Department of Social Welfare, Social Work Manual (1984, E4.1).

[599] Department of Social Welfare, Social Work Manual (1984, E4.1).

[600] Else, A, A question of adoption: Closed stranger adoption in New Zealand, 1944–1974 (Bridget Williams Books, 1991, page xii).

[601] Witness statement of Dr Anne Else (9 October 2019, para 7).

[602] Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 1998, page 223).

[603] Haenga-Collins, M, “Creating fictitious family memories: The closed stranger adoption of Māori children into white families,” Journal of New Zealand studies (2019, page 37).

[604] Adult Adoption Information Act 1985, sections 4 and 9.

[605] Witness statement of Dr Anne Else (9 October 2019, page 3).

[606] Else, A, A question of adoption: Closed stranger adoption in New Zealand, 1944–1974 (Bridget Williams Books, 1991); Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 1998, page 60).

[607] Savage, C, Moyle, P, Kus-Harbord, L, Ahuriri-Driscoll, A, Hynds, A, Paipa, K, Leonard, G, Maraki, J, & Leonard, J, Hāhā-uri hāhā-tea: Māori involvement in State care 1950–1999 (Ihi Research, 2021, page 35).

[608] Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 1998, page 233).

[609] Else, A, A question of adoption: Closed stranger adoption in New Zealand, 1944–1974 (Bridget Williams Books, 1991, page 180).

[610] NZ Press Association, “New Law Reduces Adoptions,” The Press (29 July 1966). https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19660729.2.36?phrase=2&query=New+Law+Reduces+Adoptions&snippet=true

[611] Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 1998, page 234)

[612] Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 1998, page 234); Witness statements of Dr Anne Else (9 October 2019, page 18); Ms AF (13 August 2021, paras 3.3–3.5) and Dallas Pickering (n.d., para 27); Haenga-Collins, M, Closed stranger adoption, Māori and race relations in Aotearoa New Zealand, 1955–1985, Doctoral Thesis, Australian National University (March 2017, page 7).

[613] Else, A in Savage, C, Moyle, P, Kus-Harbord, L, Ahuriri-Driscoll, A, Hynds, A, Paipa, K, Leonard, G, Maraki, J & Leonard, J, Hāhā-uri hāhā-tea: Māori involvement in State care 1950–1999 (Ihi Research, 2021, page 168).

[614] Witness statement of Dr Anne Else (9 October 2019, para 14).

[615] Ahuriri-Driscoll, A, Blake, D, Potter, H, McBreen, K & Mikaere, A, “A ’forgotten’ whakapapa: historical narratives of Māori and closed adoption, New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online,” 18(2), (2023, page 136).

[616] Children, Young Persons. and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), sections 241(1)– (2).

[617] Penal Institutions Act 1958, sections 12(1)–(2): Sentences of imprisonment for less than one month could be served in a police jail.

[618] Criminal Justice Act 1954, section 14(1).

[619] Child and Young Persons Act 1974, section 12.

[620] Transcript of evidence of Commissioner Andrew Coster for NZ Police at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 16 August 2022, pages 104–105).

[621] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (No 24), section 208(a).