Chapter 11: Faith-based institutions during the Inquiry period Ūpoko 11: Ngā whare tūāpapa-whakapono i te wā Pakirehua

558. This chapter provides background information and a structural overview on how the different faith-based institutions were set up and run, and key faith settings during the Inquiry period.

I mahi tahi te rāngai whakapono me te Kāwanatanga

Faith and State worked together

559. State and faith-based institutions have a history of working together to provide care, with the State providing financial support to faith-based institutions.

560. Many public servants were active Christians during the Inquiry period.[715] Sometimes this influenced the development of State laws and practices, including legislation governing marriage, sexuality and approaches to child welfare.[716]

561. In the early 20th century, the desire to build a responsible society resulted in what was known as the ecumenical movement – unity and co-operation across different Christian (mainly Protestant) denominations.[717] This movement also strengthened co-operation between the State and faith-based institutions.

562. The First World War and the Great Depression led to widespread unemployment for many people, and religious and voluntary welfare organisations responded to the rising levels of need this created.[718] As the State expanded its own provision of welfare support in the 1930s, it also expanded its support for the voluntary social service sector, including church-run services.[719] While churches had long been active in care provision, this substantial and guaranteed funding stream from the State to church-run services was a change from what had previously been [720]

563. Churches, particularly the Catholic, Anglican, Methodist and Presbyterian churches and The Salvation Army, were involved in care provision during the Inquiry period. In addition to the pastoral care provided by all churches, some also operated schools and / or provided other services such as unmarried mothers homes, adoption, foster care services and some residences for disabled people.

564. The total number of children’s homes grew rapidly during the early 20th century. In 1900, five orphanages were registered as charities, but by the mid-1920s, Aotearoa New Zealand had 85 private faith-based institutions and orphanages, housing approximately 4,000 children.[721]

565. By 1950 the State was regularly subsidising Christian social services, including church or charity-run homes for the elderly.[722] Other areas of church social services also received increased financial support.[723] From 1956 the government subsidised faith-based children’s homes through a ‘capitation subsidy’ of 10 shillings a week per child, the equivalent of around $31 dollars in 2024. A subsidy for up to half the cost of any approved building work was also available.[724]

566. With growing pressure on accommodation in the State’s institutions over the 1960s and 1970s, private and religious-run homes played an increasingly important role as an ‘overflow’ for overburdened State institutions. In 1977, around a quarter of the children living in church homes were State wards.[725] Of the children and young people living in homes run by voluntary agencies in 1985, 36 percent were State wards.[726]

567. By the 1970s a distinct church sector had emerged, which operated as a well-resourced component of the non-government, non-profit sector.[727] This formalised partnership meant Christian social services developed their own institutional structures beyond traditional church structures.[728]

568. There were now Christian lobby groups and national associations, such as the New Zealand Council of Christian Social Services. This council improved the bargaining power of the faith-based care sector, advocating for greater funding and more relaxed State regulations and procedures.[729]

569. By 1977 the capitation subsidy for children in faith-based care was $12.67 a week[730] ($125.55 in 2024)[731], with an additional payment of $24.35 a week if the child was a State ward. The subsidy for approved building works rose to 66 percent of the total cost.[732]

570. A 1977 review by the Department of Social Welfare into Church Social Services identified that an average cost for a child was around $57 a week:

“This means that after taking into account the capitation subsidy, family benefit, and any contribution from parents, the Church agencies are required to find the balance of about $36 a week from their own resources for each child cared for.”[733]

571. Using the consumer price index as a measure, these amounts are the equivalent today of $482.57 for the cost of each child and $304.78 for the funding shortfall.[734]

572. Church activities received substantial State funding until the 1980s, with a large increase in State funding from the 1960s to the 1980s. In 1967, about $3.9 million (about $85.8 million in 2024) was transferred from central government departments to the voluntary social service sector, which included non-church bodies such the Society for Intellectually Handicapped Children and the Crippled Childrens Society.. By 1986, a conservative estimate placed this figure at $75.6 million,[735] equivalent to $221.3 million in 2024. [736]

Ngā whakahaerenga o ngā hāhi

Governance structures of the faiths

573. The Inquiry investigated reports of abuse and neglect in the care of eight faith-based institutions:

- Catholic Church

- Anglican Church

- The Salvation Army in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Methodist Church

- Presbyterian Church

- Gloriavale Christian Community

- Plymouth Brethren Christian Church

- Jehovah’s Witnesses.

574. The Inquiry refers to faith-based institutions across all of the eight faiths investigated by including the name of the care setting and identifying the religion, such as the Star of the Sea orphanage (Catholic), or St Andrew’s Orphanage (Anglican). Another example is where the Inquiry refers to private schools and State integrated schools with special character, often where the integrated schools was formerly a private school.

575. The degree of church involvement in the settings varied. For example, in some cases there was a less direct relationship with the entities in question and the relationship was largely one of theological or spiritual oversight and affiliation. In other settings, the religious denomination owned or operated the institution referred to. Some schools were operated by faiths, other schools merely had an onsite chaplain or yearly visits from faith officials.

576. In this report the Inquiry does not always make a distinction about the relationship between the faith and the setting described unless particular context and explanation is required for the point being made in the relevant section.

Ngā Pīhopa me ngā kaiārahi whakaminenga o te Hāhi Katorika i Aotearoa

Bishops and congregational leaders of the Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand

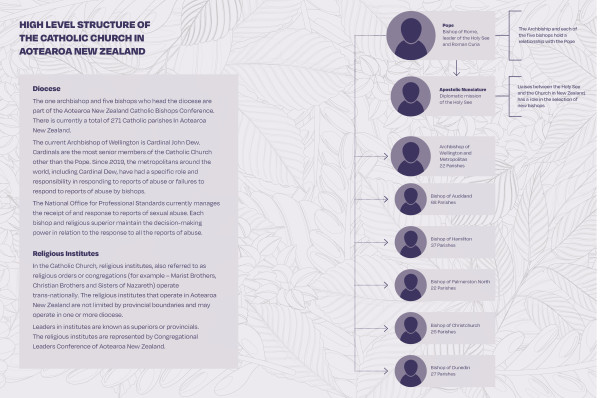

577. The worldwide Catholic Church, sometimes called the ‘universal church’, is made up of many particular or local churches, each under the leadership of a diocesan bishop appointed by the Pope. The Pope, who is the Bishop of Rome, is the leader of all these local churches. The Holy See is the name given to the Catholic Church’s central government and is led by the Pope. It operates from the Vatican City State, which is an independent sovereign territory within Italy.[737]

578. The Congregation for the Evangelisation of Peoples has oversight of Aotearoa New Zealand dioceses.[738] Only the Pope can appoint and remove bishops or intervene in dioceses. Diocesan bishops are required to make a profession of faith and oath of fidelity to the Holy See. Bishops in Aotearoa New Zealand direct their contact with the Vatican through a papal emissary.

579. The bishops and congregational leaders of the Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand (which the Inquiry refers to as the Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand) is territorially divided into one metropolitan archdiocese, and five suffragan (regional) dioceses. The Archdiocese of Wellington with the five other dioceses in Aotearoa New Zealand constitutes a province as determined by the Pope. The metropolitan is the senior bishop of the province.[739] Since 2019, the metropolitans around the world, including Paul Martin, as Catholic Archbishop of the archdiocese of Wellington, have had a specific role and responsibility in responding to reports of abuse or failing to respond to a report of abuse by bishops within their province under “Vos Estis Lux Mundi”, the new Vatican protocol for dealing with cases of abuse.

580. Dioceses are made up of various parishes, churches, schools, and other affiliated entities and institutions. Each bishop appoints priests and assistant priests, and ensures they fulfil their obligations as priests.

581. Some religious institutions (also referred to as religious orders or congregations) have both religious brothers and priest members (like the Society of Mary, known as the Marist Fathers), some only religious brother members (like the Marist Brothers) or only religious sister members (like the Sisters of Nazareth).

582. The religious institutes operating in Aotearoa New Zealand are not limited by diocesan boundaries and may be in one or more dioceses, depending on the agreement of local bishops. Bishops are required to exercise pastoral care for all the people of faith (Catholics) within a geographical region (diocese), including members of religious institutes. Alongside the dioceses and religious institutes, there are many, mostly independent and self-governing lay organisations. These are both large and small with a variety of ownership structures and legal standing. Catholic schools were owned and operated by dioceses and religious institutes before 1975. From 1975 they were integrated into the State system. The land and buildings continue to be owned by a church authority, such as a bishop, religious institute or trust / company established for this purpose.[740] The bishops, religious superiors / leaders or trust / company continues to have proprietorship of these Catholic schools but are not involved in their day-to-day operation.[741]

583. The National Office for Professional Standards was set up in 2004 and currently manages complaints of sexual abuse or sexual misconduct by clergy or members of religious orders under Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing protocol. All reports of other forms of abuse are managed by the relevant bishop, religious superior or catholic organisation. Each bishop and religious superior, or leader of a church organisation has the decision-making power in response to all reports of abuse. The image on the following page provides a simple overview structure of the Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Overview structure of the Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand

Te Hāhi Mihingare

Anglican Church

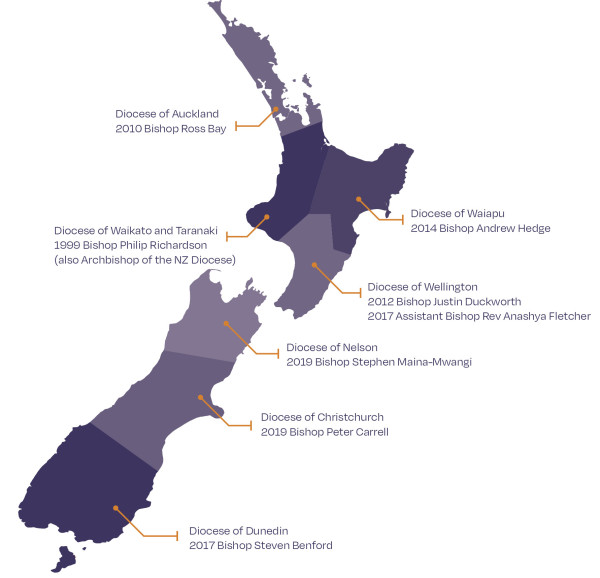

584. The Anglican Church is an autonomous branch of the worldwide Anglican Communion and is split into the church and its affiliated entities.[742] Since 1992, the Anglican Church in Aotearoa New Zealand and Polynesia (which the Inquiry refers to as the Anglican Church) has been constitutionally divided into three tikanga: Tikanga Māori, Tikanga Pasifika and Tikanga Pākehā. Three archbishops, one from each of Tikanga Māori, Tikanga Pasifika and Tikanga Pākehā form the Primacy of the Anglican Church, or in other words, lead the church.

585. The geographical division of Tikanga Māori amorangi and Tikanga Pākehā diocese can be seen in the following maps:[743]

Geographical divisions of the Anglican Church

Tikanga Māori amorangi:

Tikanga Pākehā diocese:

586. Each diocese or amorangi then consists of ministry units, parishes, schools, chaplaincies and co-operating ventures. The church is estimated to have at least 300 parishes and more than 30 schools associated with the church. The church’s primary governing body is the General Synod Te Hinota Whānui, which is made up of three houses: bishops, clergy and laity (non-ordained).

587. Every decision of the General Synod Te Hinota Whānui must be agreed to by each of the three houses and the three tikanga. The General Synod Te Hinota Whānui only meets for a week at a time, every two years. As a result, the process for change to church processes is slow.[744] The Primacy has limited influence to be able to direct change.

Te Ope Whakaora ki Aotearoa, Whītī, Tonga me Hāmoa

The Salvation Army New Zealand, Fiji, Tonga and Samoan Territory

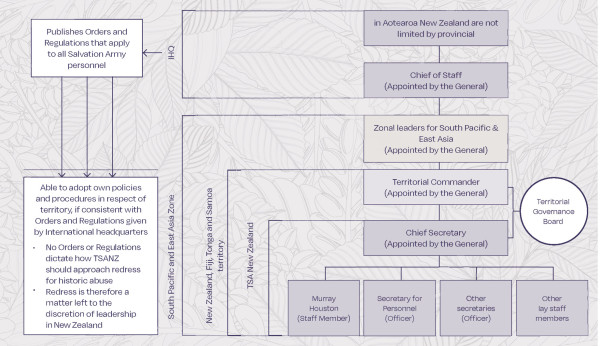

588. The Salvation Army New Zealand, Fiji, Tonga and Samoan (which the Inquiry refers to as The Salvation Army) has been active in Aotearoa New Zealand since 1883. The world-wide Salvation Army is divided into five zones. These zones are further divided into territories, which are sub-divided into commands or regions. The Salvation Army falls into the South Pacific and East Asia zone, and is part of the New Zealand, Fiji, Tonga and Samoa Territory.[745]

589. The Salvation Army has a quasi-military command structure, headed by an elected general who directs The Salvation Army operations at International Headquarters located in London. Territorial commanders and the Territorial Governance Board are responsible for the work of The Salvation Army within their territories, are subject to the control and direction of International Headquarters, and ultimately report to the general.

590. The Salvation Army in New Zealand can enact policies and procedures if they are consistent with the orders and regulations given by International Headquarters in the United Kingdom.[746]

Overview of structure and functions of The Salvation Army

591. Religious congregations in The Salvation Army are known as corps and church members as soldiers. Ordained clergy are known as officers and hold various military ranks. The Salvation Army’s structure is top-down and strongly hierarchical, and all official positions, apart from the general, are appointed, not elected.

Te Hāhi Weteriana

Methodist Church

592. The Methodist Church in Aotearoa New Zealand (which the Inquiry refers to as the Methodist Church) has been involved in caring for children in its former children’s homes, in foster care placements arranged by those homes, and in foster care placements arranged by the church. The Methodist Church also has one school, Wesley College.

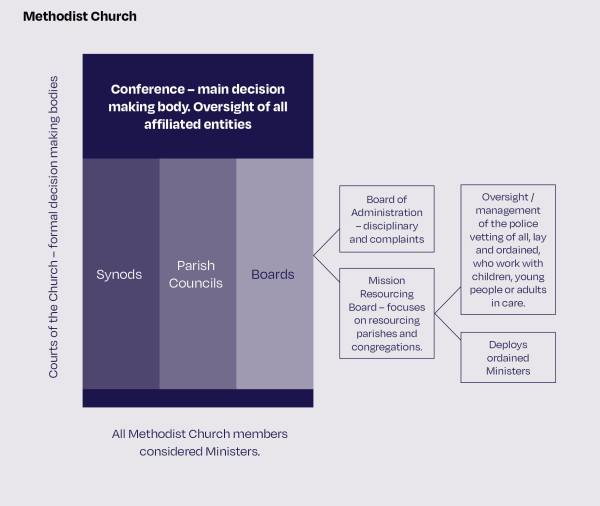

593. The governing body of the Methodist Church is known as Conference. Conference is the primary decision-making body of the church, the final authority on all matters of the church and exercises oversight over entities affiliated with the church.[747] Its decisions are binding on both lay and ordained members of the church in matters pertaining to the operation of the church.[748] Conference meets annually. Until 1983, decisions were made by a 50 percent majority.[749]

594. After 1983, the Methodist Church became a bicultural church, with two equal partners Tauiwi and Te Taha Māori. A decision of Conference after 1983 required an agreement of the two partners by consensus.[750] An increase in Pacific Peoples’ presence in the church has seen an increase in their own self-governing synods. During the Inquiry period, there were eleven regional synods with responsibility for the congregations in their region. Separate Tongan, Samoan and Rotuman synods have been added since then, and the total number of regional synods has been reduced to six.

595. The Methodist Lawbook lays down in detail the rules that govern the church. The church authorises leadership roles for presbyters and deacons, who are received into the presbyterate or diaconate.[751] The church can appoint lay members into specified roles, subject to the church’s authority.

596. The Methodist Church also has formal decision-making bodies (parish councils, synods, and boards) which, along with Conference are known as Courts of the Church.[752] The Laws and Regulations of the church sets out the powers and privileges of church members and courts and how these relate to the church’s doctrines.[753]

597. The Methodist Conference delegates various functions to its operational boards. The Board of Administration is headed by the general secretary and is the board which manages the disciplinary and complaints processes. The Mission Resourcing Board focuses on resourcing parishes and congregations. This board has a key role in deployment of ordained ministers and has oversight / management of the NZ Police vetting of all, lay and ordained, who work with children, young people or adults in care.[754]

598. There are regional Methodist Missions in many parts of Aotearoa New Zealand. Each mission is autonomous, although the boards are appointed or approved by the Conference. From the 1970s, missions took responsibility for the delivery of all social services in their region. A Conference co-ordinating body, aiming to focus policies, was reorganised in 1999 as Wesley.com and is now named the Methodist Alliance. Responsibility for local operations remains at the regional level.[755]

Overview of structure and functions of the Methodist Church

Te Hāhi Perehipitīriana o Aotearoa

Presbyterian Church of New Zealand

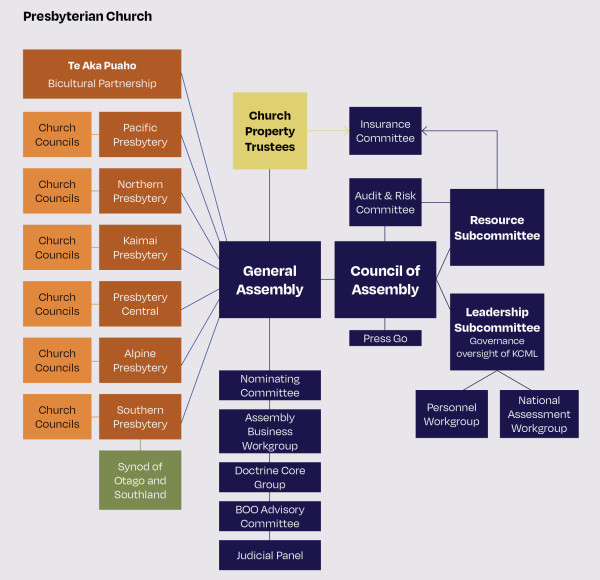

599. The Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand is governed by three courts – the General Assembly (national level), the Presbytery (regional level) and Sessnio of Elders (local level).[756]

600. The highest court is the General Assembly. It sets the policy and the direction of the church as a whole, as well as approving the various regulations that help the church to operate as an effective organisation. During the Inquiry period, the General Assembly met every year. At present, the General Assembly normally meets once every two years. The Book of Order is the church’s body of laws that incorporates all standing General Assembly decisions.

601. In 2000, there were 25 presbyteries, including Te Aka Puaho (founded in 1955), but today this has been reduced to seven presbyteries – five regional, one for Pacific congregations (since 2002) and Te Aka Puaho for Māori. Each local parish reports to its presbytery.[757] Te Aka Puaho can appoint ministers to serve nationally, whereas the other presbyteries can only appoint ministers to specific positions within specific churches.[758]

602. A National Office which supports presbyteries and parishes is based in Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington, led by the Assembly Executive Officer.[759] At parish level, the local church council (made up of elders or other elected people from the congregation) make decisions affecting the local church. If there is a minister, the council is usually led by that minister.[760]

Overview of structure and functions of the Presbyterian Church

Rōpū tautoko Perehipitīriana

Presbyterian Support

603. In addition to the General Assembly and seven presbyteries, there are seven regional Presbyterian Support Services organisations. From the late 1800s Presbyterian parishes recognised they were not capable of dealing with the increasing numbers of people living in poverty. With no basic social welfare system, these separate support organisations were established.[761]

604. Presbyterian Support Central and Presbyterian Support Otago, two of the seven support organisations, told the Inquiry they were established in the early 1900s, with both organisations initiating projects to care for orphaned and destitute children.[762]

605. Each Presbyterian Support Services organisation is independently governed. A national council representing the regional Presbyterian Support Services organisations was founded in 1983, and reports to the General Assembly. This reporting is the only formal link between the church and the Presbyterian Support Services organisations.

Te Hapori Karaitiana o Gloriavale

Gloriavale Christian Community

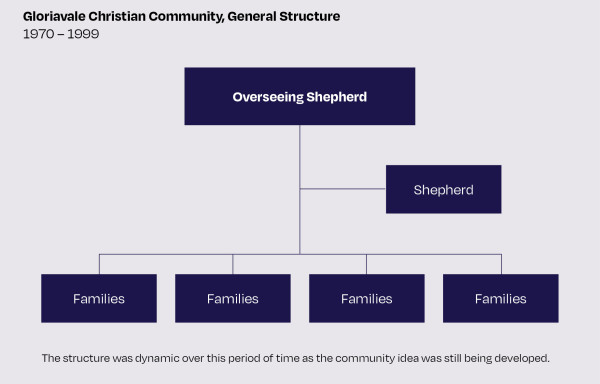

606. Gloriavale Christian Community (which the Inquiry refers to as Gloriavale) was founded in 1969 by Neville Cooper, an Australian-born, evangelical missionary, known within the community as Hopeful Christian.[763] Originally called the Springbank Christian Community, it operated a farm in North Canterbury.[764]

607. In 1991, the community bought 917 hectares of remote farmland on the West Coast. Over the next four years, they built living and dairy farming facilities. The property was named Gloriavale after Hopeful Christian’s late wife, Gloria.[765]

608. Gloriavale Christian Community is run by the Shepherds and the Servants. The Overseeing Shepherd is the principal leader. The Overseeing Shepherd is responsible to Christ and Christ alone. While the Bible is the “source of all guidance regarding Church order, doctrine and practical direction for life”, the Bible is interpreted by the Community’s leaders, ultimately and authoritatively, by the Overseeing Shepherd.[766]

609. Leaders are not elected by the members of the community. Hopeful Christian was self-appointed as the Overseeing Shepherd until his death in 2018.[767]

610. The next level of leadership is three Senior Shepherds who hold financial authority, and below the Senior Shepherds are the Shepherds and the Servants who together comprise a leadership council of 16 men.

611. From 1985 to 1995 the Shepherds were Hopeful Christian, Howard Temple and David Courage (who left in 1995) and Fervent Stedfast (who had been appointed shortly prior to David Courage’s departure).[768] Hopeful Christian and Fervent Stedfast were the authors of the document titled What We Believe, which was effectively a summary of what the leaders saw as the main principles of New Testament Christianity. The document was prepared from the mid-1980's and first published in 1989.[769]

612. Gloriavale is a strict patriarchal community with a strict hierarchy. The Overseeing Shepherds and each of the Shepherds and Servants must be male. Roles are determined by biblical criteria, emphasising men as decision-makers and breadwinners and women as mothers responsible for running the household.[770]

Overview of structure and functions of the Gloriavale Christian Community

Te Hāhi Karaitiana o Plymouth Brethren

Plymouth Brethren Christian Church

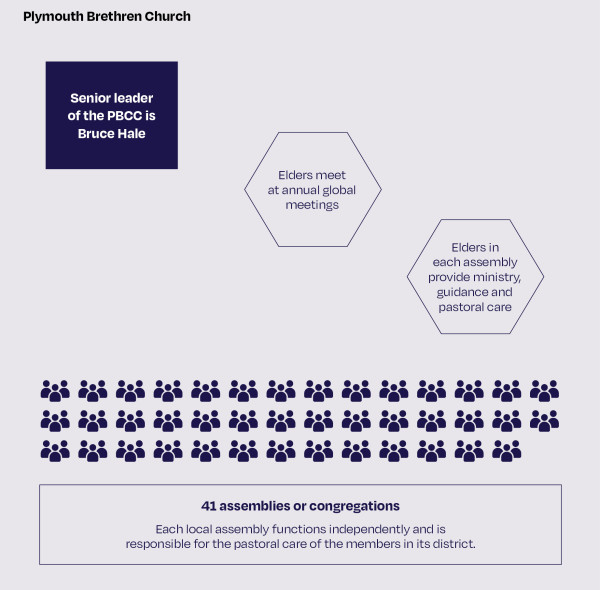

613. The Exclusive Brethren, more recently known as the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, was established in England in the early 19th century, and came to Aotearoa New Zealand in the 1850s. The Exclusive Brethren has about 50,000 members globally (across Australasia, Europe, the United Kingdom and the Americas), with around 9,006 members in Aotearoa New Zealand.[771] Members refer to themselves as the Brethren.

614. The Plymouth Brethren Christian Church in Aotearoa New Zealand is made up of 41 assemblies (or congregations). Each local assembly functions independently and is responsible for the pastoral care of the members in its district. The Brethren “consider themselves as one large family and matters of discipline decided in one assembly bind every assembly”.[772]

615. Members meet at weekly prayer meetings, Bible reading meetings, the Lord’s Supper meetings and monthly care meetings.[773]

616. The Plymouth Brethren Christian Church has no governing constituent documents other than the Bible. It does not have a formal organisational structure.[774] The most senior leader is Bruce Hales, who lives in Sydney, Australia, but there are no official positions, nor is there an established hierarchy.[775]

617. The Plymouth Brethren Christian Church told the Inquiry that elders meet at annual global meetings, where teachings about scripture are shared.[776]

618. Elders take a lead in ministering the word of God; they help co-ordinate and lead in Bible reading meetings and seek to provide guidance and pastoral care when required. There is no formal process to select elders and it is not possible to apply to become an elder.[777]

619. A person comes to be recognised as an elder by their assembly over time due to their wisdom and experience. They are not ordained.[778] Elders are not employed by the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church and do not receive any remuneration. Elders are not required to undergo any specific training and are not subject to any formal supervision or oversight.[779] The Plymouth Brethren Christian Church states however that “elders would be expected to be familiar with the holy scriptures and the ministries of the current and former senior leaders of the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church and are subject to the scrutiny of their fellow elders and their own local assembly”.[780]

Overview of structure and functions of the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church

Ngā Kaiwhakapae o Ihowa

Jehovah’s Witnesses

620. The Jehovah’s Witnesses organisation was founded in Pennsylvania in the United States in the late 19th century. Today the religion has 8.8 million active members in 239 countries.[781]

621. The Jehovah’s Witnesses organisation has been active in New Zealand since 1898, and according to the 2018 census, now has over 20,000 members in this country.[782]

622. The faith in Aotearoa New Zealand is divided into congregations. A congregation comprises publishers (also referred to as members). Some publishers serve as ministerial servants and Elders. In Aotearoa New Zealand around 228 individual Jehovah’s Witness congregations are or have been registered on the Charities Register.[783] In addition, there are charities that support the activities of the Jehovah’s Witnesses at a national level, for example, New Zealand Association of Jehovah’s Witnesses, which is also a registered charity.[784]

623. Directions and guidance on the faith’s worldwide activities are overseen by the Governing Body based in New York. The Governing Body is a council of Jehovah’s Witness Elders, or self-described “mature Christians” who look to Jehovah (God) and to Jesus Christ for direction in all matters and provide “unified theocratic direction to Branch and Country committee members worldwide”.[785] The size of the Governing Body has varied, from seven to 18 men, with all based in New York and voted in by existing Governing Body members. There are currently nine members. The faith considers that all baptised congregants, men and women, are “ministers” in the faith.[786]

624. The Governing Body supervises more than 90 branches worldwide. In each country or region, there is a Branch Office. The Branch Office is overseen by a Branch Committee. The Branch Office coordinates the religious activity of Jehovah’s Witnesses in its country or geographical area. Although religious direction and guidance comes from its headquarters in New York, the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Aotearoa New Zealand are coordinated by the Australasia Branch Office of Jehovah’s Witnesses, from its head office in Sydney.

625. Each Branch Office has a Service Department and a Legal Department.[787] The Service Department provides guidance to congregation Elders on implementing the child safeguarding policies of the faith, amongst other matters, and the Legal Department provides legal advice to the Branch Office and to congregation Elders.[788]

626. Approximately 20 congregations of Jehovah’s Witnesses are grouped together into a “circuit”. The spiritual needs of those groups of congregations are addressed by an experienced Elder known as a “circuit overseer “(also called a “travelling overseer”). Circuit overseers appoint congregation Elders. These appointments are based on a recommendation from the congregation’s body of Elders, who look to passages in scripture to determine the “good qualities” of a man (as with the Governing Body, all Elders are male).[789] Circuit overseers also decide, based on the recommendation of the body of Elders, whether an Elder should be “deleted” because he no longer meets the spiritual qualifications.[790]

627. Congregational responsibilities sit with Elders and ministerial servants. Only men are eligible for these roles. In 2023 there were around 1,576 Elders within Aotearoa New Zealand.[791]

Ngā whakaritenga tuāpapa‑whakapono i te wā o te Pakirehua

Faith-based care settings during the Inquiry period

628. The Inquiry’s Terms of Reference cover a broad variety of settings. As discussed in Part 1, they include both direct care, where the State or a faith-based institution is directly providing care for an individual, or indirect care, where the State or a faith-based institution had people or entities providing care on their behalf.

Kāinga taurima tamariki me ngā whare taurima tamariki pani

Faith-based children’s homes and orphanages

629. At the beginning of the Inquiry period, faith-based institutions were among the largest providers of residential care for children in Aotearoa New Zealand. Many of the faiths ran children’s homes including the Catholic, Anglican and Methodist churches, the Presbyterian Support Organisations and The Salvation Army. By 1960, 53 out of the 68 registered children’s homes were run by faith-based institutions.[792]

630. There were also receiving homes (or reception centres) which were short-term residences for babies and very young children, such as The Nest, run by The Salvation Army, or Catholic-run orphanages such as the Star of the Sea, or the Home of Compassion.[793]

631. Across the Inquiry period, the Anglican, Presbyterian and Catholic Churches and The Salvation Army were affiliated with children’s homes. Research conducted by the Inquiry showed:

- at least 15 homes affiliated with the Anglican church, in Ōtepoti Dunedin, Ōtautahi Christchurch, Timaru, Whakatū Nelson, Te Papaioea Palmerston North, Te Matau-a-Māui Hawke’s Bay and Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland[794]

- at least 18 homes affiliated with the Presbyterian Church, in Waihōpai Invercargill, Ōtepoti Dunedin, Lawrence (in Otago), Ōtautahi Christchurch, Timaru, Whanganui, Te Matau-a-Māui Hawke’s Bay and Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland[795]

- at least 10 homes affiliated with The Salvation Army, in Ōtepoti Dunedin, Temuka, Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington, Wairarapa, Taranaki, Te Matau-a-Māui Hawke’s Bay, Kirikiriroa Hamilton and Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland[796]

- at least 33 homes affiliated with the Catholic Church, including homes in Ōtepoti Dunedin, Ōtautahi Christchurch, Whakatū Nelson, Te Waiharakeke Blenheim, Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington, Taitoko Levin and Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland[797]

- at least six homes affiliated with the Methodist Church, in Ōtautahi Christchurch, Whakaoriori Masterton and Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.[798]

Kāinga atawhai tamariki

Foster homes

632. As well as operating children’s homes, the faiths also facilitated children entering private foster homes during the Inquiry period, co-ordinated within their religious communities. It is difficult to understand from the records how many there were or their locations.

633. Reasons for going into foster care included coming from single-parent families, health concerns, economic crises or their parents being unable to care for them.[799]

634. In some circumstances, foster care was a form of respite for the family or was used by children’s homes during the school holidays. In other cases, it was to provide a permanent living arrangement for a child.

635. Some survivors who experienced abuse in Catholic orphanages told the Inquiry that they were sent away to foster placements with Catholic families during the school holidays, when the orphanages would close for several weeks.[800]

636. Other foster care arrangements were more informal. For example, a Catholic priest suggested to a struggling mother that a childless couple who lived on church property could look after her son for a while.[801]

Kāinga taurima māmā takakau

Unmarried mothers’ homes

637. The Inquiry acknowledges that during the Inquiry period some facilities referred to as “unmarried mothers’ homes” in the report offered a range of services and were not exclusively providing care for unmarried mothers. For example, Bethany Homes (operated by The Salvation Army) also functioned as maternity hospitals.

Kāinga taurima māmā takakau Katorika

Catholic unmarried mothers’ homes

638. Several Catholic entities operated homes for unmarried mothers including Mount Magdala reformatory home and St Vincent’s Home of Compassion in Herne Bay, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, which was run by the Compassion sisters.

639. St Vincent’s Home of Compassion included a home for unmarried pregnant women, a private maternity hospital and a children’s home for babies and toddlers. It operated from 1939 to 1986.

Kāinga taurima māmā takakau Mihingare

Anglican unmarried mothers’ homes

640. The Anglican Trust for Women and Children operated St Mary’s Home in Ōtāhuhu, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. The home took in unmarried pregnant women and their babies and also ran a children’s home. In 1950 there were 29 births in the unmarried mothers’ wing of the home. This number peaked at 53 in 1957.

Kāinga taurima māmā takakau o Te Ope Whakaora

The Salvation Army unmarried mothers’ homes

641. The Salvation Army ran seven unmarried mothers’ homes, called Bethany Homes, from 1887 to 1982. Women and girls spent their pregnancies in these homes and then after birth, their babies were adopted out.

Kāinga taurima māmā takakau Perehipitīriana

Presbyterian unmarried mothers’ homes

642. The Presbyterian Church operated one home called Holly House in Ōtautahi Christchurch from 1991 to 2018. The home housed teenage mothers and their babies.

Te whakapono me te whāngai

Faith and adoption

643. Faith-based adoptions were facilitated by the Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian churches and The Salvation Army.[802]

644. From the 1940s to 1955, although social worker approval was required, most legal adoptions were arranged privately, often through the various homes housing unmarried mothers.[803] The Adoption Act 1955 introduced more comprehensive State involvement in adoptions.

645. Catholic agencies remained significantly involved in the decades that followed, facilitating adoptions that were then processed through the State.[804] Catholic social services agencies also worked with the Māori Mission in finding homes for Māori and Pacific babies.[805] Catholic entities arranged and facilitated hundreds of adoptions in Aotearoa New Zealand with Wellington Catholic Social Services recording 130 adoptions March 1961 and March 1962 alone.[806]

646. Adoption through The Salvation Army was primarily facilitated through its unmarried mothers’ Bethany Homes. Some children were also adopted out from The Salvation Army’s children’s homes. Missing records mean it is not possible to accurately estimate the number of adoptions facilitated through The Salvation Army, however it is likely to be in the high tens of thousands.[807]

647. Although private adoption agencies were not legally permitted following the Adoption Act 1955, The Salvation Army’s records show it considered itself to be running an adoption agency or programme. In a submission on the Adult Adoption Information Bill in 1981, The Salvation Army stated it was “justly proud” of the adoption programme, which is “a very important part of our overall service”.[808]

648. The Anglican Church similarly facilitated adoptions through its unmarried mothers’ homes.

649. The Inquiry has received limited information about adoption facilitated through Presbyterian Support organisations and children’s homes. However, evidence provided by these organisations indicates they had a role in adoption.[809]

650. In addition, Presbyterian Support Upper South Island provided the Inquiry with its 1997 Holly House Guidelines on Adoption. This set out how it could support “young women contemplating adoption two months before the expected birth delivery date and for a limited time after the birth of the baby”.[810] The Presbyterian Church also provided evidence that adoption was considered one of the options for care of “deprived children”.[811]

Kura tūāpapa-whakapono me ngā whare mātauranga

Faith-based schools and education facilities

651. For much of the Inquiry period, faith-based institutions have been providers of education in Aotearoa New Zealand. Catholic, Anglican, Methodist and Presbyterian churches, and the Gloriavale Christian Community, have all run or have affiliation with schools in Aotearoa New Zealand. These schools offer a range of education including primary and secondary education and boarding facilities.

652. During the early part of the Inquiry period, faith-based schools were generally private schools. The Private Schools Conditional Integration Act 1975 provided the option for private schools to integrate into the State education system. Many faith-based private schools became State-integrated with a special character. This means that the schools could become a State school, subject to the same set of standards and funding arrangements as other State schools but retaining a special character that informed how the school operated.

653. In practice, faith-based institutions tend to own the land and buildings where the State integrated school is located. Owners of the school land and / or buildings are called ‘proprietors.’ The proprietor is responsible for ensuring the facilities meet Ministry of Education standards and for maintaining the school’s special character.[812] Under the Act, certain teaching appointments, including the principal, deputy principal and director of religious studies, can be made in line with the school’s special character.[813] However, the school itself is administered by the State (via what was known as a Board of Trustees from 1989 and which was changed to the School Board in 2020 through the Education and Training Act 2020), including the teaching curriculum, teaching staff appointments and other legislative and regulatory requirements.

654. The Private Schools Conditional Integration Act 1975 significantly reduced the number of private faith-based schools in Aotearoa New Zealand. For example, by 1983, 249 Catholic and nine non-Catholic private schools had integrated into the State education system.[814]

655. There were also faith-based residential special schools. Two examples are Glenburn Centre in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, run by Presbyterian Social Services (with funding from the Department of Child, Youth and Family)[815] and Marylands School in Ōtautahi Christchurch, run by the Catholic Order of St John of God.

656. Marylands School was the subject of a separate report by the Inquiry. The findings were published in the Inquiry’s report Stolen Lives, Marked Souls.

Pehea te urunga o ngā tāngata ki ngā kura tūāpapa-whakapono

How people entered faith-based schools

657. Children and young people were often sent to faith-based schools because of their families’ religion or because their parents believed these schools provided a higher standard of education than State schools. In some cases, the schools were considered an attempt to recreate the English class system.[816]

658. Children and young people also attended some faith-based schools because they offered boarding facilities. As with faith-based children’s homes and orphanages, faith-based boarding schools were sometimes used as overflow or a last resort by the State when no other suitable placements for State wards were available.[817]

Kura Katorika

Catholic schools

659. Catholic entities ran 371 schools during the Inquiry period covering primary and secondary education. Some offered boarding facilities or were special schools for disabled and Deaf children. Marylands (1955–1983) was a private special school for disabled boys in Ōtautahi Christchurch, and St Dominics School for the Deaf (1944–1989) for Deaf children in the Te Whanganui-ā-Tara Wellington and Manawatu regions.

660. There were also four Catholic institutions that were focused on behaviour reform. These were Mount Magdala (in Ōtautahi Christchurch), Marycrest (in Te Horo), Rosemount (in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland) and Garindale (in Whakatū Nelson).

Kura Weteriana

Methodist school

661. The Methodist Church has one school in Aotearoa New Zealand, Wesley College in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. The College was first set up as the Wesleyan Native Institute in 1844. In 1911, the Methodist Charitable and Educational Trusts Act 1911 was passed, establishing the Wesley Training College Trust Board to take over the functions of the Native Education Trust and the Wesley College Executive Committee. The trust board also administered the affairs of the trust under the general control and supervision of the Methodist Conference. The Wesley College Trust Board is affiliated with the Methodist Church as representatives from the Methodist Conference are appointed to sit on the Wesley College Trust Board, which reports to the Methodist Conference.[818]

Kura Mihingare

Anglican schools

662. There are currently 37 schools throughout Aotearoa New Zealand affiliated to the Anglican Church. These schools provide primary and secondary education, some of them with boarding facilities. The Anglican Schools’ Office provides support and resources to schools.

Kura Perehipitīriana

Presbyterian schools

663. The Presbyterian Church has 20 affiliated schools. All Presbyterian schools are distinct and independent entities. The schools are governed by a board of trustees. Each school operates differently. For example, some individual board of trustees may also be members of Presbyterian Church Aotearoa, but they act independently in their school governance function. Some schools are on property owned by the Presbyterian Church Aotearoa, but this does not also mean the church has a governance role in that school.[819]

Kura noho Māori

Māori boarding schools

664. As discussed in Chapter 2, in the 19th century, missionaries from the various faiths played a role in establishing schools in Aotearoa New Zealand. Starting in 1844 with the opening of the Anglican St Stephen’s School in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, different faiths began establishing Māori boarding schools throughout the country.

665. These schools were established specifically for Māori, with the aim of providing them with the best education and to create future Māori leaders, as well as evangelise Māori. However, the leadership of these schools was predominantly non-Māori.

666. From the mid-1840s to the 1980s, these schools were the main (if not only) Māori-specific secondary school option. It was not until about the 1980s that other Māori-specific schools such as kura kaupapa were established.

667. By 1910 there were ten Māori boarding schools throughout Aotearoa New Zealand.[820]

668. By 1969 five of the schools had closed, and Hato Pāora (a school for boys) in Feilding was opened by the Society of Mary in 1948.[821] By the end of the Inquiry period there were eight Māori boarding schools still in operation.[822]

Te Kura Hapori Karaitiana o Gloriavale

Gloriavale Christian Community school

669. Gloriavale has an on-site school, the Gloriavale Christian School, which is governed by the Gloriavale Trust Board and the community management board. It has a roll of approximately 190 children aged from 5 to 16 years old, and 18 teaching staff. Teachers are self-employed and do not receive a salary as their work is unpaid and their “needs are met through membership of the community”.[823]

670. Gloriavale Christian School is a registered private school. It receives some subsidy funding from the State and is reviewed by the Education Review Office on its compliance with the registration criteria.[824]

Te Kura Karaitiana o Plymouth Brethren

Plymouth Brethren Christian Church school

671. Plymouth Brethren Christian Church told the Inquiry that children of Plymouth Brethren members customarily attend OneSchool Global schools, and that these schools are not operated or controlled by the Exclusive Brethren.

672. However, these private schools (although staffed and run by independent professionals who are not church members) are attended only by children of Plymouth Brethren. Church members are often involved in supporting the schools through volunteer work and by board membership.[825]

Ngā kura hāhi me ētahi atu whare mātauranga whakapono

Seminaries and other religious education institutions

673. The Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian and Methodist churches ran institutions for men and women preparing for religious life. These are also known as seminaries or theological colleges.

- the Catholic Dioceses’ main seminary was Holy Cross College in Ōtepoti Dunedin before it was relocated to Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, and religious congregations also had seminaries and houses of formation throughout the country. The Marist Seminary at Mount St Mary’s (originally in Napier) combined with the Holy Cross College to form the Good Shepherd College in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland in the 1990s. In 2020, the Good Shepherd College and the Catholic Institute merged to form Te Kupenga Catholic Theological College, which offers theological courses to seminarians and other people

- the Anglican Church had St John’s Theological College in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland (still in operation today), and College House (later Christchurch College) in Ōtautahi Christchurch

- the Presbyterian Church has the Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership in Ōtepoti Dunedin

- the Methodist Church has one seminary in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, Trinity Methodist Theological College, which has been co-located with the Anglican St John’s Theological College since the 1970s.

Te taurimatanga o te hunga Turi me te hunga whaikaha i ngā whakaritenga tūāpapa-whakapono

Care of Deaf people and disabled people in faith-based care settings

674. While few faith-based institutions catered for Deaf adults and disabled adults, some private and church-based organisations did open residential homes for Deaf people and disabled people. Private institutions such as Hōhepa Homes, in Te Matau-a-Māui Hawke’s Bay, opened its first residential services in 1956.[826]

675. The Catholic Home of Compassion in Island Bay, founded by Daughters of Our Lady of Compassion, a religious congregation which began in Aotearoa, operated from 1907 to 1988. It provided care for children and families in need, such as children who may have been living in insecure homes or parents needing respite.

676. As noted, Catholic Church entities operated two special schools for Deaf children and disabled children. In addition, Presbyterian Support Upper South Island financially supported Little Acre Huntsbury Home in Ōtautahi Christchurch caring mostly for disabled children.[827]

Administration |

Year |

Ministerial Portfolio |

Name of Minister and tenure |

Head of Department/Chief Executive |

Relevant legislation |

|

National Government PM: |

1949 - 1957 |

Social Welfare |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Education |

Ronald Algie (1949-1957) |

Director of Education: Clarence E Beeby (1940–1960) Superintendent of Child Welfare: Charles E Peek |

Education Act 1914 Child Welfare Act 1925 Adoption Act 1955 |

||

|

Health |

Jack Watts Jack Marshall |

Director-General of Health: Dr John Cairney |

Mental Defectives Act 1911 |

||

|

Justice |

Clifton Webb Jack Marshall |

Secretary for Justice: Samuel Thompson Barnett (1949–1960) |

Prevention of Crime (Borstal Institutions Establishment) Act 1924 Penal Institutions Act 1954 Criminal Justice Act 1954 |

||

|

Police |

Sidney Holland Wilfred Fortune Sidney Holland Dean Eyre |

Commissioner of Police:

|

Police Act 1958 |

||

|

Corrections |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

||

|

Finance |

Sidney Holland Jack Watts |

Secretary to the Treasury: Sir Bernard C Ashwin (1939–1955) Ted Greensmith (1955–1964) |

Public Revenues Act 1953 |

||

|

Prime Minister (including State Services) |

Sidney Holland |

Chairman of the Public Service Commission: Richard Campbell (1946–1953) George Bolt (1953–1958) |

Public Service Act 1912 |

||

|

Labour Government PM: |

1957 - 1960 |

Social Welfare |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Education (Education + Child Welfare Division) |

Philip Skoglund |

Director of Education: |

Education Act 1914 |

||

|

Health |

Rex Mason |

Director-General of Health: |

Mental Defectives Act 1911 |

||

|

Justice |

Rex Mason |

Secretary for Justice: |

Prevention of Crime (Borstal Institutions Establishment) Act 1924 |

||

|

Police |

Phil Connolly |

Commissioner of Police |

Police Act 1958 |

||

|

Corrections |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

||

|

Finance |

Arnold Nordmeyer |

Secretary to the Treasury: |

Public Revenues Act 1953 |

||

|

Prime Minister (including State Services) |

Walter Nash |

Chairman of the Public Service Commission: |

Public Service Act 1912 |

||

|

National Government PM: |

1960 - 1972 |

Social Welfare |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Education (Education + Child Welfare Division) |

Blair Tennant |

Director of Education: |

Education Act 1914 |

||

|

Health |

Norman Shelton |

Director-General of Health: |

Mental Health Act 1969 |

||

|

Justice |

Ralph Hanan |

Secretary for Justice: |

Prevention of Crime (Borstal Institutions Establishment) Act 1924 |

||

|

Police |

Dean Eyre |

Commissioner of Police: |

Police Act 1958 |

||

|

Corrections |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

||

|

Finance |

Harry Lake |

Secretary to the Treasury: |

Public Revenues Act 1953 |

||

|

State Services |

Keith Holyoake (1963-1972) |

Chairman of the State Services Commission: |

Public Service Act 1912 |

||

|

Labour Government PM: |

1972 - 1975 |

Social Welfare |

Norman King |

Director-General of Social Welfare: |

Adoption Act 1955 |

|

Education |

Phil Amos |

Director-General of Education: |

Education Act 1969 |

||

|

Health |

Bob Tizard |

Director-General of Health: |

Mental Health Act 1969 |

||

|

Justice |

Martyn Finlay |

Secretary for Justice |

Prevention of Crime (Borstal Institutions Establishment) Act 1924 |

||

|

Police |

Mick Connelly |

Commissioner of Police |

Police Act 1958 |

||

|

Corrections |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

||

|

Finance |

Bob Rowling Bob Tizard |

Secretary to the Treasury: Henry Lang |

Public Revenues Act 1953 |

||

|

State Services |

Jack Marshall Bob Tizard Arthur Faulkner |

Chairman of the State Services Commission: Ian Lythgoe Robin Williams |

State Services Act 1962 |

||

|

National Government PM: |

1975 - 1984 |

Social Welfare |

Bert Walker George Gair Venn Young |

Director-General of Social Welfare: Stanley J Callahan John Grant |

Adoption Act 1955 Children and Young Persons Act 1974 Disabled Persons Community Welfare Act 1975 |

|

Education |

Les Gandar Merv Wellington |

Director-General of Education: William (Bill) L Renwick |

Education Act 1969 |

||

|

Health |

Frank Gill George Gair Aussie Malcolm |

Director-General of Health: Dr H J H Hiddlestone (1973–1983) |

Mental Health Act 1969 Disabled Persons Community Welfare Act 1975 |

||

|

Justice |

David Thomson Jim McLay |

Secretary for Justice: John Fraser Robertson Stanley J Callahan |

Penal Institutions Act 1954 |

||

|

Police |

Allan McCready Frank Gill Ben Couch |

Commissioner of Police: Ken Burnside Robert Josiah Walton Ken Thompson |

Police Act 1958 |

||

|

Corrections |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

||

|

Finance |

Robert Muldoon |

Secretary to the Treasury: Noel Lough Bernie Galvin |

Public Revenues Act 1953 |

||

|

State Services |

Peter Gordon David Thomson |

Chairman of the Ian Lythgoe Robin Williams Mervyn Probine |

State Services Act 1962 |

||

|

Labour Government PM: |

1984 - 1990 |

Social Welfare |

Ann Hercus Michael Cullen |

Director-General of Social Welafare: John Grant |

Adoption Act 1955 |

|

Education |

Russell Marshall David Lange Geoffrey Palmer Phil Goff |

Director-General of Education: William (Bill) L Renwick Dr Russ Ballard Secretary for Education: Dr Maris O’Rourke |

Education Act 1989 |

||

|

Health |

Michael Bassett David Caygill Helen Clark |

Director-General of Health: Dr Ronald A Barker (1983–1986) Dr George Salmond |

Mental Health Act 1969 Disabled Persons Community Welfare Act 1975 |

||

|

Justice |

Geoffrey Palmer Bill Jeffries |

Secretary for Justice: Stanley J Callahan David Oughton |

Penal Institutions Act 1954 Criminal Justice Act 1954 Criminal Justice Amendment Act 1975 Penal Institutions Amendment Act 1980 |

||

|

Police |

Ann Hercus Peter Tapsell Roger Douglas Richard Prebble |

Commissioner of Police Ken Thompson Malcolm Churches John Anderson Jamieson |

Police Act 1958 |

||

|

Corrections |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

||

|

Finance |

Roger Douglas David Caygill |

Secretary to the Treasury: Graham Scott (1986–1993) |

Public Revenues Act 1953 |

||

|

State Services |

Stan Rodger Clive Matthewson |

Chairman of the Chief Commissioner of the State Services Commission: |

State Services Act 1962 State Sector Act 1988 |

||

|

National Government PM: Jim Bolger (1990–1997) PM: Jenny Shipley (1997–1999) |

1990 - 1999 |

Social Welfare |

Jenny Shipley Roger Sowry |

Director-General of Social Welfare: Andrew Kirkland (1991–1993) Margaret Bazley |

Adoption Act 1955 Disabled Persons Community Welfare Act 1975 Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 Protection of Personal Property Rights Act 1988. |

|

Education |

Lockwood Smith Wyatt Creech Nick Smith |

Secretary for Education: Dr Maris O’Rourke (1989–1996) Howard Fancy (1996–2006) |

Education Act 1989 |

||

|

Health |

Simon Upton Bill Birch Jenny Shipley Bill English Wyatt Creech |

Director-General of Health: Dr George Salmond Dr Christopher Lovelace Dr Karen Poutasi |

Mental Health Act 1969 Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992 Health and Disability Commissioner Act 1994 |

||

|

Justice |

Doug Graham |

Secretary for Justice: |

Penal Institutions Act 1954 |

||

|

Police |

John Banks |

Commissioner of Police: |

Police Act 1958 |

||

|

Corrections |

Paul East |

Chief Executive: |

|

||

|

Finance |

Ruth Richardson |

Secretary to the Treasury: |

Public Finance Act 1989 |

||

|

State Services |

Bill Birch Paul East Jenny Shipley Paul East Simon Upton |

State Services Commissioner: Don Hunn Michael Wintringham |

State Sector Act 1988 |

Footnotes

[715] Buckley, B, ‘As loyal citizens...’: the relationship between New Zealand Catholicism, the state and politics, 1945–1965, Doctoral Thesis, Massey University (2014, page 202).

[716] Adhar R, & Stenhouse, J (eds), God and government: The New Zealand Experience (Otago University Press, 2000).

[717] Evans, J, Church state relations in New Zealand 1940–1990, with particular reference to the Presbyterian and Methodist churches, Doctoral Thesis, University of Otago (1992, pages 26 and 54–56).

[718] Tennant, M, O'Brien, M & Sanders, J, The history of the non-profit sector in New Zealand (Office for the Community and Voluntary Sector, 2008).

[719] Evans, J, “Government support of the church in the modern era,” Journal of Law and Religion, 13(2), (1998, pages 517–530, page 518).

[720] Evans, J, Church state relations in New Zealand 1940–1990, with particular reference to the Presbyterian and Methodist churches, Doctoral Thesis, University of Otago (1992, page 82).

[721] Dalley, B, Family matters: Child welfare in twentieth-century New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 1998, page 134).

[722] Tennant, M, O'Brien, M & Sanders, J, The history of the non-profit sector in New Zealand (Office for the Community and Voluntary Sector, 2008, page 20).

[723] Evans, J, “Government Support of the Church in the Modern Era,” Journal of Law and Religion, 13(2), (1998, pages 517–530, page 518); Evans, J, Church state relations in New Zealand 1940–1990, with particular reference to the Presbyterian and Methodist churches, Doctoral Thesis, University of Otago (1992, page 43).

[724] Cahill, T, Mitchell, A, Nixon, A, Sherry, B & Wetterstrom, J, Church social services: A report of an Inquiry into childcare services (Department of Social Welfare, 1977, page 12).

[725] Tennant, M, The fabric of welfare: Voluntary organisations, government and welfare in New Zealand, 1840–2005 (Bridget Williams Books, 2007, page 104).

[726] Craig, T & Mills, M, Care and control: The role of institutions in New Zealand (New Zealand Planning Council, 1987, page 37).

[727] Evans, J, Church state relations in New Zealand 1940–1990, with particular reference to the Presbyterian and Methodist churches, Doctoral Thesis, University of Otago (1992, page 322).

[728] Evans, J, Church state relations in New Zealand 1940–1990, with particular reference to the Presbyterian and Methodist churches, Doctoral Thesis, University of Otago (1992).

[729] Lineham, P, “The voice of inspiration? Religious contributions to social policy,” in Dalley, B & Tennant, M (eds) Past judgement: Social policy in New Zealand history (Otago University Press, 2004, pages 57–74).

[730] Cahill, T, Mitchell, A, Nixon, A, Sherry, B & Wetterstrom, J, Church Social Services: A report of an Inquiry into childcare services (Department of Social Welfare, 1977, page 3).

[731] Calculated from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand inflation adjustment calculator using general consumer price index as a comparator, Reserve Bank of New Zealand website, Inflation calculator (accessed February 2024), https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/monetary-policy/about-monetary-policy/inflation-calculator.

[732] Cahill, T, Mitchell, A, Nixon, A, Sherry, B & Wetterstrom, J, Church Social Services: A report of an Inquiry into childcare services (Department of Social Welfare, 1977, page 3).

[733] Cahill, T, Mitchell, A, Nixon, A, Sherry, B & Wetterstrom, J, Church Social Services: A report of an Inquiry into childcare services (Department of Social Welfare, 1977, page 12).

[734] Calculated from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand inflation adjustment calculator using general consumer price index as a comparator, Reserve Bank of New Zealand website, Inflation calculator (accessed February 2023), https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/monetary-policy/about-monetary-policy/inflation-calculator.

[735] Tennant, M, O'Brien, M, & Sanders, J, The History of the Non-profit Sector in New Zealand (Office for the Community and Voluntary Sector, 2008, page 20).

[736] Both conversions calculated from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand inflation adjustment calculator using general consumer price index as a comparator, Reserve Bank of New Zealand website, Inflation calculator (accessed February 2023), https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/monetary-policy/about-monetary-policy/inflation-calculator.

[737] The Holy See has ratified a number of international conventions, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

[738] Code of Canon Law (1983), canon 333 §1.

[739] Code of Canon Law (1983), canons 431–436.

[740] Witness statement of Cardinal John Dew for the Archdiocese of Wellington and the Metropolitan Diocese (23 September 2020, page 10).

[741] Witness statement of Cardinal John Dew for the Archdiocese of Wellington and the Metropolitan Diocese (23 September 2020, page 11).

[742] Title G, Canon XIII of Holy Orders in the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand & Polynesia (1992), section 6.1. The Anglican Church does not take direction from overseas but presents itself as in full communion with the Church of England and all other churches of the Anglican Communion.

[743] Witness statement of Archbishop Philip Richardson for the Anglican Church (12 February 2021, pages 11–12).

[744] Witness statement of Archbishop Philip Richardson for the Anglican Church (12 February 2021, pages 9–10).

[745] Witness statement of Colonel Gerry Walker for The Salvation Army (18 September 2020, page 22).

[746] Witness statement of Colonel Gerry Walker for The Salvation Army (18 September 2020, page 25).

[747] Opening submissions of the Methodist Church of New Zealand, Wesley College Board of Trustees and Wesley College Trust Board (18 October 2022, para 3.4).

[748] Methodist Church of New Zealand, Laws and Regulations of the Methodist Church of New Zealand (2021, pages 5 and 84).

[749] Methodist Church of New Zealand, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 452 (questions 2–7) (24 May 2022, page 6).

[750] Methodist Church of New Zealand, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 452 (questions 2–7) (24 May 2022, page 2).

[751] Methodist Church of New Zealand, Laws and Regulations of the Methodist Church of New Zealand (2021, page 5).

[752] Methodist Church of New Zealand, Laws and Regulations of the Methodist Church of New Zealand (2021, page 10).

[753] Methodist Church of New Zealand, Laws and Regulations of the Methodist Church of New Zealand (2021).

[754] Methodist Church of New Zealand, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 452 (questions 2–7) (24 May 2022, page 4).

[755] Methodist Church of New Zealand, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 452 (questions 2–7) (24 May 2022, page 1).

[756] Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand, ‘General Assembly’.

[757] Transcript of submissions of Matthew Hague, counsel for the Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand at the Inquiry’s Faith-based Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 19 October 2022, pages 295–296).

[758] Transcript of submissions of Matthew Hague, counsel for the Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand at the Inquiry’s Faith-based Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 19 October 2022, page 296).

[759] Transcript of submissions of Matthew Hague, counsel for the Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand at the Inquiry’s Faith-based Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 19 October 2022, page 296).

[760] Transcript of evidence of Wayne Matheson for the Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand at the Inquiry’s Faith-based Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 19 October 2022, page 298).

[761] Transcript of opening statement from Presbyterian Support Central and Presbyterian Support Otago at the Inquiry’s Faith-based Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 19 October 2022, page 240).

[762] Transcript of opening statement from Presbyterian Support Central and Presbyterian Support Otago at the Inquiry’s Faith-based Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 19 October 2022, page 240).

[763] Gloriavale Christian Community, A life in common: The experience of the Gloriavale Christian Community, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (2018, page 8).

[764] Gloriavale Christian Community, A life in common: The experience of the Gloriavale Christian Community, Response to Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (2018, pages 9–12).

[765] Gloriavale Christian Community, A life in common: The experience of the Gloriavale Christian Community, Response to Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (2018, pages 9–12).

[766] Gloriavale Christian Community, A life in common: The experience of the Gloriavale Christian Community, Response to Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (2018, page 12).

[767] Gloriavale Christian Community, A life in common: The experience of the Gloriavale Christian Community, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (May 2021, page 30).

[768] Transcript of evidence of Howard Wendell Temple and Rachel Stedfast on behalf of Gloriavale Christian Community at the Inquiry’s Faith Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 13 October 2022, page 44).

[769] Transcript of evidence of Howard Wendell Temple and Rachel Stedfast on behalf of Gloriavale Christian Community at the Inquiry’s Faith Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 13 October 2022, page 46).

[770] Gloriavale Christian Community, A life in common: The experience of the Gloriavale Christian Community, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (May 2021, page 19).

[771] Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, Natural Justice response letter (10 January 2024, page 9).

[772] Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (23 April 2021, page 2).

[773] Notes from meeting with representatives of the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church (29 November 2022, pages 4–5).

[774] Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (23 April 2021, page 2).

[775] Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (23 April 2021, page 2).

[776] Notes from meeting with representatives of the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church (29 November 2022, page 6).

[777] Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (23 April 2021), Appendix 1: Overview of the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, paras 7–8.

[778] Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (23 April 2021, page 2).

[779] Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (23 April 2021, page 2).

[780] Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 1 (23 April 2021, page 2).

[781] JW.Org > About Us > Frequently Asked Questions > How Many of Jehovah’s Witnesses Are There Worldwide (Jehovah’s Witnesses, 2023) https://www.jw.org/en/jehovahs-witnesses/faq/how-many-jw/.

[782] “Seventy-Five years of ‘legally establishing’ the Good News in New Zealand,” Jehovah’s Witnesses (7 March 2022) https://www.jw.org/en/news/region/new-zealand/Seventy-Five-Years-of-Legally-Establishing-the-Good-News-in-New-Zealand/.

[783] Charities Services Ngā Ratonga Kaupapa Atawhai (Charities Register), https://register.charities.govt.nz/CharitiesRegister/Search accessed 24 April 2024.

[784] Charities Services Ngā Ratonga Kaupapa Atawhai, Charity Summary of the New Zealand Association of Jehovah’s Witnesses https://register.charities.govt.nz/Charity/CC29352, noting there is a set of rules included in the charity documents.

[785] Australian Child Sexual Abuse Royal Commission into Institutional responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Report of Case study no 29, (Commonwealth of Australia, October 2016), p 15.

[786] JW.org, “Do Jehovah’s Witnesses Have Women Ministers?” (“Yes, worldwide Jehovah’s Witnesses have several million women ministers. They are a great host of preachers of the good news of God’s Kingdom. Psalm 68:11 says prophetically of those ministers: “Jehovah himself gives the saying; the women telling the good news are a large army”).

[787] Witness statement of Paul Gillies, The United Kingdom Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (2 December 2019, para 9)

[788] Witness statement of Paul Gillies, The United Kingdom Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (2 December 2019, para 9)

[789] Supplementary witness statement of Shayne Mechen, Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (21 June 2023, para 4). These scriptures known as ‘inspired qualifications” can be found at: 1 Timothy 3:1-13; Titus 1:5-9; James 3:17&18 and 1 Peter 5:2 & 3.

[790] Memorandum to Counsel Assisting the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Historical Abuse in State Care and in the Care of Faith-based Institutions (“Inquiry”) on behalf of Jehovah’s Witnesses of New Zealand (1 November 2019, para 3.5).

[791] Jehovah’s Witnesses interview transcript with the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (8 March 2023, pages 20-21).

[792] Evans, J, “Government support of the church in the modern era,” Journal of Law and Religion, 13(2), (1998, pages 517–530, page 519).

[793] Brief of evidence of Sonja Cooper and Amanda Hill on behalf of Cooper Legal at the Inquiry’s Contextual Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 5 September 2019, para 38).

[794] Department of Social Welfare, Directory of residential facilities for disturbed children in New Zealand (1975, pages 22, 24, 26–27, 29, 31, 34); Oranga Tamariki, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 14, Schedule 2 (22 January 2021, pages 2, 12, 21).

[795] Department of Social Welfare, Directory of residential facilities for disturbed children in New Zealand (1975, pages 21, 23–24, 28, 30, 37–39); Presbyterian Support Southland, Submission settings out a narrative and analysis of the information requested in Schedule A (2024, page 2); Oranga Tamariki, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 14, Schedule 2 (22 January 2021, pages 12–13).

[796] Department of Social Welfare, Directory of residential facilities for disturbed children in New Zealand (1975, pages 24, 27– 28, 32, 37); Oranga Tamariki, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 14, Schedule 2 (22 January 2021, pages 7, 14); Hawke’s Bay children’s holding trust, Our history (accessed 22 March 2024), https://hbcht.org.nz/our-history/; Cussen, I, Help where help was needed: Single mothers and the Salvation Army Bethany home in 1960s-70s Auckland (Auckland History Initiative, 5 August 2021) https://ahi.auckland.ac.nz/2021/08/05/help-where-help-was-needed-single-mothers-and-the-salvation-army-bethany-home-in-1960s-70s-auckland/.

[797] Department of Social Welfare, Directory of residential facilities for disturbed children in New Zealand (1975, pages 22–23, 31–32, 34–35, 38); Ponter, Elizabeth, Interface: A review of Catholic social services New Zealand (National Directorate, Catholic Social Services 1986, pages 7–8); Oranga Tamariki, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 14, Schedule 2 (22 January 2021, pages 5–6, 12, 14–16, 20–23).

[798] Department of Social Welfare, Directory of residential facilities for disturbed children in New Zealand (1975, pages 21, 25, 35)

[799] Witness statement of Charlene Montgomery (May 2022, page 2).

[800] Letter from Cooper Legal to the National Office for Professional Standards on behalf of Alexandra Murray (23 May 2018, pages 6–7); Witness statements of Ms NJ (10 February 2022, page 6); Anne Hill (28 September 2020, page 5) and Linda Taylor and Janice Taylor (5 March 2021, paras 123, 128–129). Private session of Mr SI (5 August 2021, page 7).

[801] Written account of K.C. (24 April 2021, page 8).

[802] Witness statement of Dr Anne Else (9 October 2019, page 3).

[803] Witness statement of Dr Anne Else (9 October 2019, page 4).

[804] Witness statement of Lesley Hooper on behalf of the bishops and congregational leaders of the Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand (16 June 2022, page 6).

[805] Archdiocese of Wellington, Social Welfare Work in the Archdiocese (n.d., page 2).

[806] Between March 1961 and March 1962 alone, Wellington Catholic Social Services recorded 130 adoptions. See Catholic Social Services Summary of Statistics, March 1961–March 1962 (page 1).

[807] Sumner, B, External consultation prepared for the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (15 August 2022, pages 17–18).

[808] Adult Adoption Information Bill submission by Major Eunice Eichler (16 February 1981), in Sumner, B, External consultation prepared for the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (15 August 2022, pages 19–20).

[809] Presbyterian Support Central told the Inquiry about an unsuccessful adoption arrangement where a child was returned to Berhampore Children’s Home after being abused by the man who had adopted him; Berhampore Childrens Home – Abuse (2005, pages 7–11).

[810] Presbyterian Support Upper South Island, Holly House Guidelines re Adoption (December 1997, page 1).

[811] Presbyterian Church of New Zealand, Care of deprived children (n.d., page 2).

[812] Brief of evidence of Helen Hurst for the Ministry of Education at the Inquiry’s Marylands School (St John of God) Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 7 October 2021, paras 3.19–3.20); Ministry of Education website, Types of schools and year levels, (last reviewed 28 April 2022), https://www.education.govt.nz/school/new-zealands-network-of-schools/about/types-of-schools-and-year-levels/.

[813] Ministry of Education, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 468 (7 July 2022), page 6.

[814] Brief of evidence of Helen Hurst for the Ministry of Education at the Inquiry’s Marylands School (St John of God) Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 7 October 2021, para 3.19).

[815] Education Review Office, Evaluation of the residential behaviour schools (2008, page 11).

[816] Cook, M, Private education: Elite private schools (Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 2012, page 3), https://teara.govt.nz/en/private-education/page-3.

[817] Tennant, M, The fabric of welfare: Voluntary organisations, government and welfare in New Zealand, 1840–2005 (Bridget Williams Books, 2007, page 107).

[818] Witness statement of Reverend Tara Tautari on behalf of the Methodist Church of New Zealand (1 July 2022, page 7).

[819] Presbyterian Church, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 286 (30 November 2021, pages 2–3).

[820] The 10 Māori denominational boarding schools in 1910 were as follows. For boys: Te Aute College (Hawke’s Bay), St Stephen’s Boys’ School (Auckland), Waerenga-a-hika College (near Gisborne), Hikurangi College (Wairarapa). For girls: Hukarere Protestant Girls’ School (Napier) St Joseph’s Roman Catholic Girls’ School (Napier), Queen Victoria School for Māori Girls (Auckland), Turakina Māori Girls’ School (Marton) and Te Waipounamu College (near Christchurch), Department of Education, “Education: Native Schools,” AJHR, E-3 (1911, page 10).

[821] Calman, R, Māori education – mātauranga: Māori church boarding schools (Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 2012, page 4), https://teara.govt.nz/en/maori-education-matauranga/page-4.

[822] They were Te Aute College (Hawke’s Bay), St Stephen’s School (Auckland), Queen Victoria Māori Girls’ Boarding School (Auckland), St Joseph’s Māori Girls’ College (Napier), Hato Pāora College (Feilding), Hato Pētera College (Auckland), Hukarere Girls’ College (Napier) and Turakina Māori Girls’ College (Marton). Remaining open today are St Joseph’s, Hukarere, Te Aute and Hato Pāora.

[823] Complaints Assessment Committee v Faithful Pilgrim [2022] NZTDT 2021/35, para 3.

[824] Brief of evidence of Secretary for Education and Chief Executive Iona Holsted for the Ministry of Education at the Inquiry’s State Institutional Response Hearing (Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, 8 August 2022, page 41).

[825] Notes from meeting with representatives of the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church (29 November 2022); Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce No 1 (23 April 2021, page 3).

[826] National Advisory Committee on Health and Disability, To have an ‘ordinary life’ - Kia whai oranga ‘noa’: Background papers to inform the National Advisory Committee on Health and Disability (2004, page 30).

[827] Letter from Presbyterian Support Upper South Island to Renée Habluetzel (15 January 2007, page 2).