Catholic Church

Structure and governance of the Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand

The worldwide Catholic Church, sometimes called the “universal church”, is made up of many “particular” or “local” churches, each under the leadership of a bishop appointed by the pope. The pope, who is the bishop of Rome, is the leader of all these local churches. The Holy See is the name given to the Catholic Church’s central government and is led by the pope. It operates from the Vatican City State, which is an independent sovereign territory within Italy.

The Congregation for the Evangelisation of Peoples has oversight of Aotearoa New Zealand dioceses. Only the pope can appoint and remove bishops or intervene in dioceses. Bishops are required to make a profession of faith and oath of fidelity to the Holy See.

The Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand is territorially divided into one metropolitan archdiocese, and five suffragan (regional) dioceses. The Archdiocese of Wellington with the five other dioceses in Aotearoa New Zealand constitutes a province as determined by the pope. The metropolitan is the senior bishop of the province. Since 2019, the metropolitans around the world, including Cardinal Dew, as Catholic Archbishop of Wellington, have had a specific role and responsibility in responding to reports of abuse or failing to respond to a report of abuse by bishops within their province under “Vos Estis Lux Mundi”.

Dioceses are made up of various parishes, churches, schools, and other affiliated entities and institutions. Each bishop appoints priests and assistant priests, and ensures they fulfil their obligations as priests.

Some religious institutes have both religious brothers and priest members (like the Society of Mary, known as the Marist Fathers), some only religious brother members (like the Marist Brothers) or only religious sister members (like the Sisters of Nazareth).

The religious institutes operating in Aotearoa New Zealand are not limited by diocesan boundaries and may be in one or more dioceses, depending on the agreement of local bishops. Bishops are required to exercise pastoral care for all the people of faith (Catholics) within a geographical region (diocese), including members of religious institutes. Alongside the dioceses and religious institutes, there are many, mostly independent and self-governing lay organisations. These are both large and small with a variety of ownership structures and legal standing. Catholic schools were owned and operated by dioceses and religious institutes before 1975. From 1975 they were integrated into the State system. The land and buildings continue to be owned by a church authority, such as a bishop, religious institute or trust/company established for this purpose. The bishops, religious superiors/leaders or trust/company continues to have proprietorship of these Catholic schools but are not involved in the day-to-day operation.

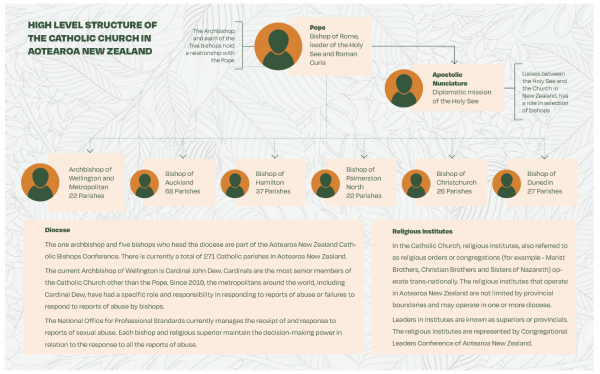

The National Office for Professional Standards currently manages the receipt of and response to reports of sexual abuse against clergy and religious under Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing protocol. All reports of other forms of abuse are managed by the relevant bishop, religious superior or catholic organisation. Each bishop and religious superior, or leader of a church organisation have the decision-making power in response to all reports of abuse. Diagram four provides a simple overview structure of the Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Diagram Four: Overview structure of the Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand

Ngā hātepe a te Hāhi Katorika - Processes of the Catholic Church

Before Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing

Prior to the 1990’s, Catholic Church leaders responded to reports of abuse in an ad hoc manner, usually under conditions of great secrecy. Few records were kept, and even when reports of abuse were documented in some way, records were often incomplete.

Cardinal Dew has acknowledged the approach of the Catholic Church to redress and cases of abuse before 1985 was not well handled. Survivors were often not believed. Offending priests were transferred and offending continued, and, as Cardinal Dew told the inquiry, in relation to the years before 1985, “that was a terrible time and it should never ever have happened like that.” He also told the inquiry there were a lack of guidelines around redress, and any requests were likely dealt with on an ad hoc basis.

During the period 1990-1998, bishops and leaders of religious institutes used various interim protocol documents when responding to reports of sexual abuse. In 1994, the leaders of Catholic religious institutes, as members of the Congregational Leaders Conference of Aotearoa New Zealand, published a draft document called “Suggested Procedures in Cases of Allegations of Sexual Abuse by a Religious” which was revised in 1995 and approved in 1996. The religious institutes agreed to publish the procedures, but there is no evidence all the religious institutes agreed to follow the same process.

Between 1990 and 1992, the New Zealand Catholic Bishops’ Conference (Bishop’s Conference) sought advice on the establishment of a “protocol” for bishops and religious superiors/leaders to use when responding to allegations of sexual misconduct. The Bishops’ Conference established a small working party to review, adapt, and revise protocols developed overseas for recommended use in our country.

In 1993, the Bishops’ Conference developed a document, Catholic Church Guidelines on Sexual Misconduct by Clerics, Religious, and Church Employees, which is sometimes referred to as the “Provisional Protocol”. It dealt only with sexual misconduct. Despite the title, the contents of the document are focused on sexual misconduct by clergy.

The guidelines recommended the six Aotearoa New Zealand bishops each set up an advisory committee to assist with responding to reports of abuse. The committees were known as the “Sexual Abuse Protocol Committees” or “Professional Standards Committees”.

The 1993 Provisional Protocol represented an effort to provide a more consistent response to reports of sexual abuse by priests and religious than had previously been the case. However, as noted earlier, it was of limited scope and its primary focus was dealing with alleged abusers rather than responding to victims and survivors. Also, Catholic Church authorities did not always know about the Provisional Protocol, nor did they always follow it. Although the current and previous versions of Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing state that the protocol was first “adopted” in 1993, there is no evidence dioceses or religious institutes collectively agreed to any national policy before Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing in 1998.

Catholic Church processes now

In 1998, Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing: Principles and procedure in responding to complaints of sexual abuse by Clergy and Religious of the Catholic Church in New Zealand was issued. This represented an attempt to shift towards a consistent national process for responding to reports of sexual abuse.

Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing relates only to reports of sexual abuse by clergy or male and female religious. It does not extend to reports of abuse against lay employees or volunteers. Nor does it extend to reports of other forms of abuse. Individual Catholic Church authorities developed their own policies and processes to address reports of abuse falling outside of Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing.

Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing requires each bishop to establish an Abuse Protocol Committee and urged each religious institute to make use of the services of those committees when required. The primary functions of the Abuse Protocol Committees were to:

- receive and investigate reports of abuse

- advise the respondent and receive their response

- make recommendations to the bishop or religious superiors leaders on findings and outcomes relevant to the report.

In 2004, the National Office for Professional Standards was established by the Mixed Commission. From 2004 to 2017 the National Office for Professional Standards provided support to Catholic Church authorities on handling reports of sexual abuse. Catholic Church leaders continued to manage the response to all abuse reports, also making decisions about how to respond to survivors of abuse. Processes and outcomes varied between Catholic Church authorities.

From 2017, the National Office of Professional Standards managed receipt and response to the reports of sexual abuse. The work of the diocesan/regional Abuse Protocol Committees was moved to a single entity titled the Complaints Assessment Committee which reviews the reports of sexual abuse received by or passed to the National Office for Professional Standards. The terms “complaint” and “complainant” have been commonly used by members of the Catholic Church to describe reports of abuse made in the context of Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing protocol, and those people who come forward as part of that protocol to disclose their experience of abuse.

Failure to honour commitments to Māori

We found no evidence that the Catholic Church involved Māori in the design or implementation of redress protocols or policies, including Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing. The Catholic Church said it regarded engagement with Māori as extremely important but made no meaningful effort to engage with Māori on redress process design. Despite the Catholic Church coming to Aotearoa New Zealand to “look after” Māori. The Bishops Conference made a bicultural commitment to Māori in 1990, before the development of Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing. The Church’s adoption of a reo Māori name Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing is the only expression of biculturalism in the document. Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing does not mention Māori, tikanga Māori, or te Tiriti. There is no evidence that the way Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing was delivered showed the commitments made by the Catholic Church to Māori.

The current head of the National Office for Professional Standards accepted Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing did not include anything that reflected te Tiriti, tikanga Māori, aspects of Pacific people’s culture or the accessibility needs of disabled people or Deaf people. There is no requirement for staff, including the committees established to consider claims and assessors used to investigate claims, to have training in tikanga Māori or experience of Māori in care. Currently, none do.

Catholic Church authorities have not collected data on survivors’ cultural background or risk factors in their lives, and have not understood the nature or impact of abuse on these people. During the course of the inquiry, the Catholic Church said it would begin a research project into the experiences of Māori in the care of the Catholic Church. At the time of this report, this work is still in development.

Policy and process

The four principles of the current version of Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing are:

- a compassionate response to a Complaint: we will treat all people involved through a complaint with compassion, respect and fairness

- any attempt to sexualise a pastoral relationship is a betrayal of trust, an abuse of authority and professional misconduct

- in any inquiry, the quest for truth will be paramount, and will be based on the principles of natural justice

- any person responsible for abuse will be held to account.

With the approval of the chair of the Complaints Assessment Committee, the National Office for Professional Standards appoints an investigator. The investigator is under a contractual relationship with the Church to carry out the investigation and is therefore not fully independent. According to the Catholic Church, this arrangement is a normal contractual arrangement. The investigator is not required to be trained in the impact of tūkino, or abuse, harm or trauma, or in tikanga Māori.

The National Office for Professional Standards currently administers the policy and is now the contact point for survivors making reports of sexual abuse. Its director and staff do not make decisions on reports, but rather triage reports to ensure they are within the scope of the policy and, with the approval of the Complaints Assessment Committee chair, they appoint an investigator.

The National Office for Professional Standards director, Virginia Noonan, told us that its role was not to believe or disbelieve anyone who came forward to disclose abuse. Ms Noonan’s evidence is that the complaint process is an inquiry rather than a listening process. Its function is to expedite the processing of reports of sexual abuse. Expert Dr Doyle told us that the first response to a survivor should be “a human response, not a bureaucratic approach”.

An investigator contacts the survivor directly and prepares a report which goes to the Complaints Assessment Committee, which assesses it and sends its recommendations to the relevant local bishop or religious superior or leader who remains the ultimate decision-maker. Therefore, outcomes continue to vary among each Catholic Church authority.

The Complaints Assessment Committee is made up of six volunteers appointed by the New Zealand Catholic Bishops Conference and whose identities are not made public. Neither the Complaint Assessment Committee nor the National Office for Professional Standards hold full information on the final outcomes of claims. The National Office for Professional Standards has recently started collecting some information on final outcomes of reports of sexual abuse, but this information is incomplete. It does not, for example, include the amounts of redress payments made to survivors.

Cooper Legal has acted for many survivors of abuse associated with the Catholic Church. It provided us with examples of investigation practices that it considered were questionable. These include:

- an investigator sought a survivor’s criminal records, suggesting a starting point of disbelief

- an investigator inappropriately disclosed information to a survivor’s family members for corroboration purposes

- an investigator risked re-traumatising a survivor because their lines of inquiry went beyond what was reasonable, and also because more investigators have become involved and seek further interviews with the survivor

- the Complaints Assessment Committee was supposed to reach a conclusion on “the balance of probabilities”, but in reality, it applied a criminal standard of proof, namely “beyond reasonable doubt”

- a copy of an investigator’s report was not made available to the survivor.

An investigator’s report is a vital document because it is considered by the Complaints Assessment Committee, who then recommend to a bishop or religious superior/leader whether to accept or reject the report of sexual abuse. The majority of survivors who spoke with us did not receive a draft for them to comment on. Virginia Noonan told us that survivors are given a copy of the investigation report in redacted form if they ask for it. She also said the Church was “very mindful” of Privacy Act considerations. The Act applies to personal information of all individuals referred to in the investigator’s report.

The “quest for the truth” principle applied by Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing feels to some survivors like an investigation into whether the survivor can prove the abuse happened. The search for corroboration of a survivor’s account takes great importance. Whether the alleged abuser is alive or dead should not, in itself, affect the weight of the survivor’s account. Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing principles – compassion, respect, fair treatment of all involved, holding the perpetrator to account – appear to hold less sway over the minds of those evaluating a report of sexual abuse.

Not all in the Catholic Church adopt such a starting point. For example, Father Tim Duckworth, New Zealand provincial of Society of Mary, (also known as Marist Fathers), said no-one would come to this process and lie about such a thing as sexual abuse, adding that “within seven seconds of meeting with them, you know that they’re not lying … [and you] say to them, ‘I believe what you’re telling me and I’m sorry about it. You got hurt at a time when you were a lovely, often young person who’d come into our care and we didn’t protect you’”.

Committee members read the investigator’s report and any supporting documents and form their own view about the merits of the report of sexual abuse. Investigators used to indicate whether they considered the report of sexual abuse proven, but that requirement was discontinued in 2020. The Committee decides, by majority view, whether a report of sexual abuse is, on the balance of probabilities, proven. If it upholds a report of sexual abuse, it may recommend a financial payment, although not a specific amount. It may also recommend an apology and counselling. The Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand has not initiated an inquiry into the systemic issues that contribute to abuse or failed responses within the Catholic Church, despite this being part of its terms of reference.

Prior to this inquiry, the dioceses and religious institutes did not centrally hold information about abuse that has been reported to Catholic Church authorities or the records of decision-making about any redress. In response to this inquiry, this information is now being centrally collated by Te Rōpū Tautoko, a group coordinating Catholic Church engagement with this inquiry, on behalf of the Catholic Church entities. Whether this information will form the basis of a national database in response to ongoing and future reports of abuse made it the church is not known. It has never set up a national database to hold reports about abuse that have been reported to the various dioceses and religious institutes.

The National Office for Professional Standards has not yet carried out an annual audit of the Committee’s work, as it is required to do, to ensure consistency of approach and adherence to the principles of Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing. As a result, there is no information about whether the church’s system that is responsible for the national response of Catholic Church authorities to reports of sexual abuse is working as intended. There is some indication that feedback has been recently sought from those people who report sexual abuse, about what is working, or not, from their perspective and involving them in the design or reform of the response process. However there has been no systemic process to engage survivors in the design or reform of the response process. There has not been any systematic attempt to seek feedback from those people who report sexual abuse about what is working, or not, from their perspective or involve them in the design or reform of the response process.

Final decision

In the context of the church process, the relevant bishop or religious superior/leader has decision-making power in the outcomes for those people who report abuse by their clergy or religious members. The redress outcomes vary significantly amongst Catholic Church authorities. The committee sends a letter to the relevant bishop or religious superior with a summary of the investigation and its recommendation. The individual, whether bishop or religious superior/leader, making the final decision about the report of sexual abuse does not appear to have the level of detail available to the Committee. For example, Cardinal Dew said he received a letter with a summary of what the Complaints Assessment Committee has decided and recommends. There is no criteria or guidance about how to reach this decision, beyond what is contained in Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing. There are no records kept on the reasons for decisions and no resulting cumulative knowledge bank.

Cardinal Dew said that in about half of the cases he would seek legal advice on the amount of financial compensation to offer. In the other cases, he would decide on his own. He said that the Archdiocese of Wellington offered sums ranging up to $25,000. He characterised such payments as a “pastoral gesture” to “help [survivors] in their recovery, acknowledging that they’ve been terribly hurt and a few thousand dollars is not going to make a big difference in their life, but in a pastoral way it may help them to move on to do something they’ve never been able to do, to buy something”.

A bishop or religious superior is not required to make a decision within any specified time. Some people who have reported abuse said they experienced delays at this point, although why is not clear. The church has not provided us with information to show how often bishops or religious superiors accept or reject the Committee’s recommendation.

Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing allows a person seeking redress or the respondent to ask for a review of the redress process. The review: “is not an independent evaluation of whether there is substance in any of the grounds for complaint, but whether the procedures of Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing have been followed. A review of process is not a review of the outcomes reached by the Complaints Assessment Committee or the Church Authority.”

Both the person who reported the abuse and alleged perpetrator can ask for a review of the way a decision was reached, that is, whether it followed the procedures set out in Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing, but they cannot ask for a review of the decision itself.

Financial claims

A pastoral letter in 1987 said bishops should “do whatever seems reasonable and best to help the victim of any sexual misconduct committed by a priest”. Such language suggests generosity, but the reality appears to be otherwise. Many survivors expressed great dissatisfaction with the size of their compensation payment, which they often described as insultingly low in light of the abuse they had suffered. A briefing paper provided by the church based on initial data collected indicated a number of payments had been made over the relevant period, with the average payment being about $30,000, although payments ranged from $1,000 to $152,000.

In 2002, certain church leaders began discussions with their legal advisors about the financial implications of a “flood of complaints” reaching the church. In September of that year, heads and representatives of some of the dioceses and religious institutes met to discuss these financial implications. They agreed that the need to “exercise responsible stewardship over the resources that have come mainly from the Catholic people”. The gathering agreed that the church would base its assistance on ACC’s assessment criteria. If an individual had already made a claim to ACC, the church would cover any difference between ACC’s payments and the actual cost of an approved treatment. If the church made any ex-gratia payments to top up ACC assistance or to help those ineligible for ACC assistance, it would use mediators to determine the size of those payments. Mediators would have regard to the levels or percentages of impairment used by ACC in determining payments.

This sounded like a good approach to calculating payments, but in practise the church was highly inconsistent in the way it determined financial redress and non-financial redress for that matter. In June 2003, the Bishop of Auckland, Pat Dunn, proposed that the church should reach agreement on a maximum payment amount. He noted the Marist Brothers had a maximum of $12,000 and the Society of Mary a maximum of $30,000.

The church also did not appear to have a clear process for determining contributions to survivors’ legal costs, nor any focus on supporting survivors during the redress process until the latest version of Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing (2020) which introduced the provision of therapeutic counselling during this inquiry’s process. The church provided non-monetary redress to survivors who requested it. This could take the form of such things as flights and accommodation to attend a restorative justice meeting, or educational support for children and grandchildren. It often denied those who reported abuse from accessing therapeutic support, or provided it only after settlement on a very restricted basis.

Cardinal Dew said the church was caught between wanting to help survivors and having only limited resources, but added that “we do the best we can for them”. However, this is not the impression most survivors are left with. As one family member of a survivor explained it, approaching the church felt more like “going up against Goliath”, given that “bigger people with more resources” had been up against the Catholic Church and “did not get anywhere”.

A Path to Healing Abuse that falls outside Te Houhanga Rongo

The church has no nationally co-ordinated process for responding to claims of sexual abuse by those who are not clergy or members of religious institutes, such as lay members or volunteers. Nor does it have a nationally co-ordinated process for responding to reports of physical, emotional, psychological or reports of neglect. Church entities have thought about this in the past.

Each diocese or religious institutes has its own way of responding to reports of non-sexual abuse. Some have a written process, while others have none. Sister Susan France from the Sisters of Mercy told us that her religious institute followed no specific process, but simply applied a “pastoral approach” to resolving reports of non-sexual abuse. It decided whether to undertake investigations on a case-by-case basis. They are investigated to the extent considered appropriate in the circumstances. The complaints received by the church vary and there is no “one size fits all”.

Where a survivor has been abused by more than one Catholic Church authority, different policies and processes may apply to abuse that is outside the scope of Te Houhanga Rongo – A Path to Healing. The legal structures of the various independent Catholic Church entities in Aotearoa New Zealand potentially creates a barrier for survivors, especially those harmed in multiple institutions. The absence of a single response process for all types of abuse, along with a single point of entry into that one process – creates real difficulties for survivors. It unnecessarily complicates the task facing a survivor looking to navigate the systems and also does not structure the process around the survivor’s needs.

Bishops and religious superiors also decide whether to accept or reject reports about non-sexual abuse (and sexual abuse by lay members and volunteers). They do not systematically collect or share information about the outcomes of these reports of abuse, so the church is not in a position to fully assess whether decisions are consistent, equitable or satisfy complainants’ needs. Nor can the church always determine whether systemic issues are at work behind the individual reports of non-sexual abuse or sexual abuse by lay persons, including volunteers. Having this information helps it revise or introduce policies and practices to safeguard against further abuse. We could find only very limited evidence to suggest survivors had any input into the development the response and redress processes, that these processes were accessible to disabled people, or that there was any accommodation of individual cultural needs of the people who disclosed their experience of abuse to the Catholic Church.

Disciplinary processes in response to clergy and religious who are abusers

We have seen that there have historically been structural issues in the Catholic Church, with bishops and religious superiors removing abusers from their positions and transferring them to other locations where they continue to abuse, rather than starting formal or informal disciplinary processes.

There has always been a distinction in canon law for dealing with sexual abuse by ordained clergy such as bishops, priests and deacons, and non-ordained members of religious institutes, being religious brothers and sisters. It can be more difficult to dismiss ordained men, as removing them from the clerical state involves the sacrament of Holy Orders.

Disciplinary processes have changed over time. Important changes were introduced by the 1983 Code of Canon Law; the Motu Proprio issued by Pope John Paul II in 2001 (and its revision in 2010), and the Motu Proprio issued by Pope Francis in 2019.

Priests

Since 2001, in cases involving an ordained cleric abusing a child, the Ordinary (usually the bishop) must report the abuse to the Holy See advising what he has done about it and seeking approval for a trial or an extra-judicial process.

Local bishops only have the power to limit a priest’s ministry, but not remove him from the priesthood. This power to limit includes cancelling a license or practicing certificate, or imposing a restriction. A bishop can also ask a religious superior/leader to remove a member of a religious institute from the diocese. These actions can be taken independently of the Holy See (pope). Any limitation imposed on a priest is only temporary and means that a priest still retains their status. Removal from the clerical state (making a priest no longer a priest) is imposed as a punishment or it may be granted at the priest’s own request. Removal from the clerical state for sexual abuse of a minor can only be imposed by the Holy See. A Catholic priest may voluntarily request to be removed from the clerical state. However, only the pope can grant a priest a dispensation from celibacy which is an obligation for clerics.

Often, priests have been encouraged to seek voluntary laicisation (reduced to lay status), as the disciplinary processes enacted by the Holy See are lengthy and complex.

Non-ordained religious

Religious superiors can restrict the ministry of religious brothers or sisters but need to seek a dismissal or dispensation from vows from the major superiors, who are accountable to the pope. Crimes of sexual abuse by religious must also be reported to the local Ordinary, usually the bishop.

Some Church entities keep priests, brothers, and sisters who are abusers as members of their diocese or religious institute, as they consider that they can be better supervised through a safeguarding plan and therefore this reduces the potential for further harm. Other Church entities have a different approach.

Disciplinary processes of bishops who are abusers and the exclusive power of the pope

The position is even more limited with bishops, as only the pope can impose restrictions on a bishop’s ministry. In a disciplinary sense, bishops are answerable only to the pope and real accountability demanded of bishops depends solely on the pope. The difficulties arising from this were demonstrated recently in the case of Charles Drennan, former bishop of the Diocese of Palmerston North.

On 7 May 2019, Pope Francis issued the Motu Proprio ‘Vos Estis Lux Mundi’, which requires the metropolitan to report allegations of abuse by bishops and their equivalents to the Holy See. Under Vos Estis Lux Mundi the metropolitan (currently for Aotearoa New Zealand Cardinal Dew, as Archbishop of Wellington) is responsible for the conduct of an investigation in relation to a report of abuse against a bishop of their province. While the metropolitan can ask for the help of “qualified persons” in conducting the investigation, the ultimate responsibility for the investigation remains with the metropolitan.

Cardinal John Dew, as Archbishop of Wellington and metropolitan, had to implement Vos Estis Lux Mundi shortly after it was issued, in response to a report of abuse of a young woman that had been made against Bishop Charles Drennan. It may be the first time Vos Estis Lux Mundi was used anywhere in the world to respond to a report of abuse against a bishop. In September 2019 Charles Drennan wrote a letter of resignation to Pope Francis in respect of his position as Bishop of Palmerston North. The resignation was formally announced on 4 October 2019.

It was not until nearly a year later, on 25 September 2020, that the Holy See advised Cardinal Dew of its decision on conditions to impose on Bishop Drennan’s future. The Holy See decided to stop Charles Drennan taking part in any public ministry, and to place restrictions on him in relation to his living arrangements (which had to be outside the diocese of Palmerston North), travel, religious clothing and participation in events as a bishop.

Despite Charles Drennan’s resignation as bishop of Palmerston North, at the time of this report he remains a bishop in the Catholic Church. Cardinal Dew told the inquiry in his evidence “I really don’t know why he is still a bishop”. The Diocese of Palmerston North is responsible for meeting the costs of Charles Drennan’s living expenses and rents a house from the Diocese of Auckland, for him to live in. An important consideration is the ongoing monitoring and supervision of Charles Drennan’s compliance with these restrictions. Cardinal Dew told the inquiry that he was informed “very categorically” by Cardinal Filoni, who was the then prefect of the relevant congregation of the Holy See, that Cardinal Filoni had responsibility for Charles Drennan through the Apostolic Nuncio in Aotearoa New Zealand. It is difficult to understand how Church officials from the Holy See in Rome can monitor restrictions imposed on a bishop living in Aotearoa New Zealand. Real concerns arise about the safety of others when only the Holy See can make certain decisions.

The significant delays in this process raise important questions about the efficiency and effectiveness of the Holy See maintaining the ultimate authority over the future ministry of bishops and the disciplinary process for priests who are subject to reports of abuse.