Anglican Church

The Anglican Church is an autonomous branch of the worldwide Anglican Communion and is split into the “core” church and its affiliated entities. Since 1992, the Anglican Church in Aotearoa New Zealand and Polynesia has been constitutionally divided into three Tikanga: Tikanga Māori, Tikanga Pasifika and Tikanga Pākehā. Three Archbishops, one from each of Tikanga Māori, Tikanga Pākehā and Tikanga Pasifika form the “Primacy” of the Anglican Church, or in other words, lead the church.

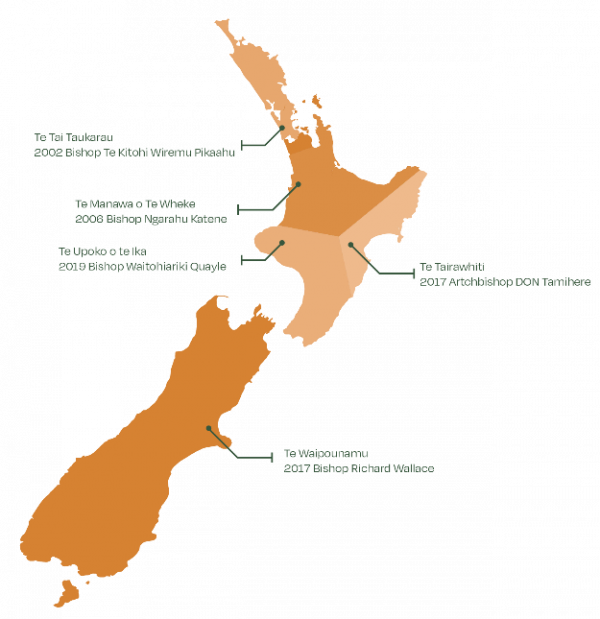

The geographical division of Tikanga Pākehā diocese and Tikanga Māori amorangi can be seen in the following maps:

Diagram Five: Geographical divisions of the Anglican Church

Each diocese or amorangi then comprises of ministry units, parishes, schools, chaplaincies and co-operating ventures. The church is estimated to have at least 300 parishes and more than 30 schools associated with the Church. The church’s primary governing body is the General Synod Te Hinota Whānui, which is made up of three houses: bishops, clergy and laity (non-ordained).

Every decision of the General Synod Te Hinota Whānui must be agreed to by each of the three houses and the three tikanga. The General Synod Te Hinota Whānui only meets for a week at a time, every two years. As a result, the process for change to church processes is slow. The primacy has limited influence to be able to direct change.

Anglican Church processes prior to 2020

The Anglican Church has had no single point of entry for claims. Rather, the bishop of the relevant diocese investigates and responds to claims individually.

The church has no national policy document to guide bishops’ responses to reports of abuse. Instead, bishops have relied on a section of the church’s code of canons known as Title D, which sets out the standards of conduct for clergy and others associated with the church. Title D does not provide a redress process for survivors. It sets out a disciplinary process which can lead to an abuser being removed from office.

The church has a number of affiliated entities including social service agencies, education services such as schools and theological colleges, charitable organisations (including residences and previously orphanages and adoption agencies), and pastoral care services, including youth groups. These entities vary from being semi-autonomous to fully autonomous from the church. Some have developed their own claims processes. The role of the church in the claims process of an affiliated entity varies depending on its formal relationship with the church. From some of the evidence we heard, it can also depend on the individual bishop and their desire to be involved in the process.

The church makes a distinction between a complaint and a claim related to abuse. Complaints are addressed under the Title D disciplinary process, which asks questions about whether an alleged abuser is fit to remain in office. A claim, according to Archbishop Philip, is concerned with redress. While the church aimed to be “fulsome” in its redress process “to be frank, the focus on redress has been consequent to us examining the handling of complaints”.

Bishop Ross Bay also saw complaints as having a disciplinary focus and claims as being focused on compensation and restitution. He acknowledged that this was a technical distinction, and that survivors disclosing abuse were likely to be seeking redress. Bishop Peter Carrell on the other hand, thought that a complaint involved disputed facts whereas in a claim the church has accepted the survivor’s disclosure, and is working with them on redress. These are very different meanings from senior leaders within the church.

Failure to honour commitments to Māori and Pacific peoples in development of redress policies

We have seen no evidence of Māori or Pacific people being involved in the development of the church’s responses to abuse in care.

In 2018, Tikanga Pākehā circulated a policy document, Addressing Abuse in Church Care. Church leaders told us that Tikanga Pākehā did not consult with the other two Tikanga branches before releasing the document. The document contained some references to tikanga Māori principles, but these were removed from a revised version in 2019. Church leaders explained that this was due to the failure to consult. It had decided to remove the values until further discussions had been held among all branches of church.

This reflects broader issues with the church’s structure. Although the three branches appear to be equal, the reality is that Tikanga Pākehā controls the bulk of resources. The unequal distribution of assets has potential implications for the ability of Tikanga Māori to respond to reports of abuse.

The church also acknowledged that it had not made information about redress processes available in reo Māori or any languages other than English.

Lack of transparency

Church leaders have acknowledged that processes have not been accessible, and that the church was not taking steps to proactively seek out survivors, or to reach survivors from marginalised communities.

At the time of publication, the church’s website provided basic information about reporting abuse but, it did not inform survivors about the process, the support they might receive, or the range of possible outcomes including financial compensation, apology, and counselling.

Some dioceses have used posters listing helpline numbers and naming contact people, but these posters have been limited in number and prominence, only in English, and lacking information about the redress process. Even when survivors made contact with the church, they were not given any written information or guidelines about the process that would be followed.

Bishop Bay acknowledged that the church had a responsibility to seek out and care for survivors and was not doing so effectively. Bishop Carrell acknowledged that there could be a connection between the lack of information about redress and low numbers of survivors coming forward. The failure to have nationally accessible and transparent policies across survivors, and access to funding for legal or other appropriate advice, seems stark when compared to church assets of at least $2,872,000,000.

Process and policy documents show no consideration of Deaf and disabled people or those with other vulnerabilities.

The church’s response to reports of abuse

We have seen no evidence that the church has ever made a formal decision that Title D should be used as a basis for responding to reports of abuse or assessing claims. Nor have we seen any policy to provide guidance for bishops on how to apply the Title D process to redress. Archbishop Philip Richardson told us that Title D’s purpose had always been on discipline and fitness to minister, and he regretted that the church’s focus had often been on those questions rather than on the needs of the complainant.

This is one of many issues that we have identified, and church leaders have acknowledged, with respect to the church’s approach to reports of abuse.

Up to 2020, bishops played a crucial role in the application of Title D. Each bishop is independent, which means that different approaches have been taken in different dioceses or amorangi.

In the past, dioceses have adopted processes and policies relating to claims of sexual harassment, and have established small committees to investigate claims and make findings. These committees have appeared to focus more on discipline than claims processes. So far as we are aware, no diocese has developed a formal claims policy, though one Anglican-affiliated school adopted a policy on historic abuse claims after this inquiry was established.

Overall, diocesan autonomy combined with the lack of national policy has produced processes that are ad hoc and inconsistent. Archbishop Richardson acknowledged that the current structure had a built-in potential for inconsistency, and had “failed” the church and survivors, and that as a result the church had no single cohesive process. Redress, whether monetary or non-monetary, differed from diocese to diocese and from one affiliated entity to another, if it was offered at all. Such inconsistency, he said, was “unfair and unacceptable”. He said institutions also differed in the records they had kept, the financial and human resources at their disposal, and the number of lawyers and other external advisors they sought help from.

Bishops have also felt conflict between their responsibility to survivors and their other duties. Bishops are responsible for licensing clergy within their dioceses, and as part of that role they are obliged to provide support and pastoral care for other clergy. However, until a policy change in 2020, they were also responsible for responding to disclosures of abuse, and for disciplining abusers. Bishops and survivors told us that these obligations conflicted.

At ordination, bishops take an oath to both seek out and care for those in need and provide pastoral care to clergy “Bishops are sent to lead by their example … They are to be Christ’s shepherds in seeking out and caring for those in need ... They are to heal and reconcile, uphold justice and strive for peace … They are to ordain, send forth and care for the Church’s pastors.”

Bishop Bay agreed that survivors of abuse are people in need within the words of the ordination and that the church, and Bishops, have a role to seek out and care for survivors. There was little evidence of steps taken by the church to proactively seek out survivors of abuse and care for them.

Bishops have faced a conflict between their duty to provide pastoral care to clergy members and their moral obligation to support survivors. The church’s process is neither co-ordinated, consistent nor transparent. Survivor Jacinda Thompson said a bishop should not be simultaneously offering a clergy member pastoral care and making disciplinary decisions about that same person. She said no one would “accept a judge also acting as a support person for the accused” and she recommended splitting the roles. Bishop Ross Bay said “the relationship between bishops and clergy can make it difficult for bishops to make objective and good decisions”, but the 2020 changes to Title D went a long way towards removing this tension.

We heard that, rather than pursuing disciplinary action against alleged abusers, bishops have sought reconciliation between abusers and survivors. As part of the Title D process, survivors have been invited to mediation with their abusers. Survivors told us that these processes led to mutual accusations, or “he said, she said” debates that caused survivors further distress and anguish.

Some survivors told us mediation was a bishop’s first port of call when faced with a sexual abuse allegation and moved to other avenues only when mediation failed. We saw Nelson diocese policies on general standards of behaviour from 2006 that showed mediation was a strongly promoted option, even in indecent exposure and indecent assault cases.

Some in the Church, including professionals such as Yvonne Pauling, said they considered it inappropriate for dealing with reports of sexual abuse as it relied on the survivor and the accused meeting with each other to work through the abuse allegations, which survivors found traumatising. It was also unclear why mediation was being used to deal with such sensitive subject matter “the experience of relying on mediation, or having it as an option, in the complaints process has been confusing and unsatisfactory”.

We heard that bishops have sometimes bypassed the Title D process altogether and encouraged those accused of abuse to resign. Archbishop Richardson said it was “disappointing that [resignation] has been at times used as a way of avoiding … responsibility” for a clergy member’s actions. He said canon law was clear that this was not an option, and any bishops who acted in this way today would themselves face disciplinary action.

Even when a bishop followed the Title D process through to completion, clergy members who were found guilty of abuse were often insufficiently sanctioned by the church and were not removed from office when they should have been. Archbishop Richardson cited the example of survivor Robert Oakly, who was sexually abused by Archdeacon Bert Jameson in the Nelson area in the 1960s. Jameson was subsequently convicted of offences relating to sexual abuse however, “Jameson wasn’t deposed from holy orders and was able to continue to represent himself as a priest of the church” until after his conviction. The Archbishop said: “I simply don’t believe that the church did not know [about Jameson’s actions].”

The Anglican Church has no national policy on reporting abuse to secular agencies, such as Police and Oranga Tamariki. The Church often failed to report abuse, and in some cases actively discouraged survivors from going to these agencies. Archbishop Philip Richardson acknowledged the experience of one survivor who told us of a “failure of process”. He said that she and others should have been supported to go to Police by the Church.

Survivors have told us that the church’s haphazard and inconsistent processes did not bring them the healing they sought. Robert Oakly said the process of seeking redress was “almost actually worse than the event itself, and I wonder if [the payment offered] is even worth it”. Another survivor, Margaret Wilkinson, said she incurred legal fees of $10,000, which the church refused to contribute to, instead offering her six counselling sessions. She said succinctly: “I felt re-victimised”.

Survivors also said that, as part of the process, they were not given information about how much money the church was likely to offer. The church has rarely disclosed settlement amounts or other outcomes, but it told us payments had averaged about $30,000 and had ranged from $1,000 up to $100,000. The church estimated it had received 579 abuse complaints, of which 161 claims have settled and 27 remain outstanding or are ongoing.There are 394 claims where the status is unknown. The estimates of numbers are based on reports of abuse made to the Church and its affiliated entities, such as schools and care organisations. We have good reason to believe, however, that the number of abuse claims the church received or processed is understated because we know that due to historic intentional and unintentional destruction of records, historical records kept are incomplete.

Bishop Bay acknowledged the church had “failed to alert people to the fact that we could consider, say, financial redress or other [forms of redress]”. One anonymous survivor told us she wanted the school to acknowledge it should have given her more support, should have recommended, or helped her get, independent legal advice, should have discussed going to police, and should have helped her get counselling. The church has no policy on funding independent legal advice or representation, a deficiency people inside and outside the church have long recognised and sought to rectify.

Calls for change

Calls for change stretch back many years. In 1989, the Reverend Patricia Allan wrote a letter to Archbishop Brian Davis pointing out the “urgent need to critically examine the underlying issues surrounding this present crisis [of the abuse in the church]”. In 1993, Nerys Parry, a psychologist used by the church in redress claims, wrote to Bishop Bruce Moore complaining about the variation in guidelines employed by each diocese to deal with sexual harassment and recommending bishops agree on a set of national guidelines and draw up a complaints procedure for sexual misconduct.

In 2002, a media article referred to a group of female survivors of abuse by clergy that had been pushing for the establishment of an independent avenue for complaints within the church, such as an ombudsman for church affairs. About a year later, an unknown author or authors drew up draft guidelines on how to respond to sexual abuse by clergy and recommended establishing a special unit to manage claims.

Archbishop Richardson said nothing became of the draft guidelines, and the recommended work had not been carried out. Then in 2016, and again in 2017, Cooper Legal wrote to the church about its lack of a clear process for investigating and responding to complaints.

Despite all these calls, the church continued to persist with the same poor disciplinary process to deal with reports of abuse.

Changes to the policy in 2020

Changes to Title D came into force in early 2020, partly in response to some of these concerns. Among other changes, a new two-tier system was introduced, in which breaches of standards could be defined either as misconduct (any intentional, significant or continuing departure from standards, including abuse) or the less serious unsatisfactory conduct.

When a complaint is received, a national registrar determines whether it should be investigated as misconduct or unsatisfactory conduct. Bishops no longer determine claims of misconduct. Instead, these are referred to a Title D Tribunal for determination. The survivor is supported by a church advocate, whereas previously the survivor represented themselves.

Archbishop Richardson told us that these changes had “greatly reduced” the roles of bishops in the church’s disciplinary processes. Bishops no longer have active decision-making roles. While they formally have a role because it is Bishops that issue licences and have jurisdiction, they must now follow the recommendations of the Registrar and Tribunals as to outcomes.

Bishop Bay said removing bishops from decision-making would also remove the conflict between their duties to survivors and clergy, by shifting “critical decisions about the process of a complaint to a more objective forum, with processes that will be applied more consistently across the whole Anglican Church”.

The Commission is yet to see evidence of the effect of these changes.