The Salvation Army

The Salvation Army has been active in Aotearoa New Zealand since 1883. Internationally, The Salvation Army is divided into five zones. These zones are further divided into territories, which are sub-divided into commands or regions. The Salvation Army in Aotearoa New Zealand falls into the South Pacific and East Asia zone, and is part of the New Zealand, Fiji, Tonga and Samoa Territory.

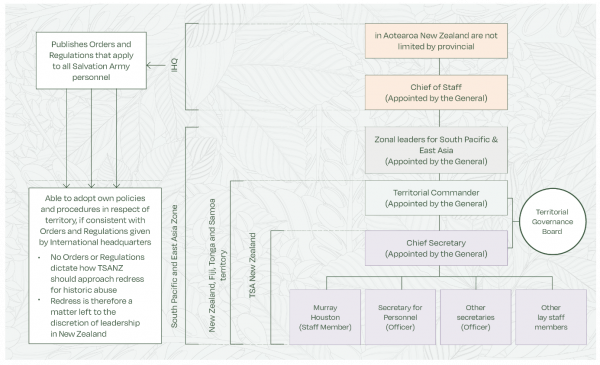

The Salvation Army has a quasi-military command structure, headed by an elected General who directs The Army operations at International Headquarters located in London. Territorial Commanders and the Territorial Governance Board are responsible for the work of The Salvation Army within their Territories, are subject to the control and direction of International Headquarters, and ultimately report to the General.

The Salvation Army in New Zealand can enact policies and procedures if they are consistent with the orders and regulations given by International Headquarters in the United Kingdom. Those headquarters have issued no orders and regulations about how the New Zealand territory should approach redress, so its leadership here is free to largely act autonomously.

Diagram Six: Overview of structure and functions of The Salvation Army

Religious congregations in The Salvation Army are known as Corps and church members as soldiers. Ordained clergy are known as officers and hold various military ranks. The Army’s structure is top-down and strongly hierarchical, and all official positions, apart from the General, are appointed, not elected.

Salvation Army claims process

The Salvation Army has appointed a single individual to make all decisions about claims of abuse in children’s homes, where most abuse took place. Murray Houston has overseen the claims process for former residents since 2003. He was The Salvation Army’s commercial manager when appointed to this role, but subsequently also filled the role as The Salvation Army’s Referral Officer. Mr Houston has broad autonomy and discretion to settle claims and according to The Salvation Army, has the ability to seek input and guidance as required. He follows an established process that has evolved over time, however there are no written policy documents or guidelines. Mr Houston has no training in tikanga Māori or trauma-informed engagement with survivors. Settlements usually involve a financial payment and apology. Sometimes counselling, and other forms of non-monetary redress may be offered as well.

The Salvation Army ran 11 children’s homes during the twentieth century, but the last of these closed in 1999. The State placed children in the homes, as did their parents or guardians, voluntarily. We cannot state with total accuracy how many children went through the homes, but Colonel Gerry Walker told us the number was in the thousands. Although we cannot say with accuracy how many Māori children were placed in The Salvation Army’s homes, we understand it to be a significant number. Between 2001 and August 2020, The Salvation Army had received 238 claims of abuse in children’s homes.

Early responses

Reports of abuse were usually made to the local congregation, or corps, and its manager investigated. Between January 2000 and August 2003, The Salvation Army received 10 reports of abuse in care. Janet Lowe was one of those to make a report. She also tried to connect with other survivors from Salvation Army children’s homes, and a front-page story in The Evening Post in 2001 highlighted her efforts to get redress.

Early claims were overseen by the church leadership. Within the organisation, there was a general disbelief that abuse could have occurred in The Salvation Army’s children’s homes. The Salvation Army took a legalistic approach to early claims, which were dealt with by its insurer, which used a law firm and Queen’s Counsel to help with this work. Legal defences were relied on. The law firm wrote to Janet Lowe, for example, to say it doubted her claim would be successful, adding that it “could be defeated on a number of fronts”, including by the limitation defence.

The Salvation Army had no formal policies or procedures in place to deal with these early claims. Its lawyers largely guided interactions with survivors, and claims were dealt with in an ad hoc manner.

That changed after a documentary about abuse in Australian Salvation Army homes aired in 2003, prompting survivors in Aotearoa New Zealand homes to come forward. By September of that year, 45 survivors had lodged claims, and the church began to realise the abuse was more prevalent and serious than originally thought, and that a different approach was needed.

Then Territorial Commander, Commissioner Shaw Clifton, appointed Murray Houston to deal with the claims. He worked with The Salvation Army’s leadership, insurer and lawyers to assess and respond to claims. However, tensions soon surfaced between the insurer and lawyers, who preferred the existing legalistic approach, and The Salvation Army’s leadership team, who preferred a more empathetic, survivor-focused approach. Mr Houston eventually became the sole point of contact for survivors who bought claims. He has personally dealt with every complainant since. At the time of his appointment, Mr Houston had no background, training or experience in dealing with claims of this nature. He has not subsequently received any training.

Over time, correspondence with survivors became less legalistic. There were still references to the limitation defence (something that could be found in correspondence to survivors right up till 2014), but these were outnumbered by references to The Salvation Army’s stated preference not to deal with claims on a strict legal basis.

Current process

The claims process has remained relatively unchanged since 2003. However The Salvation Army provided evidence that its process has evolved over time as its understanding of the impact of abuse has changed. The Salvation Army has never conducted any formal review of how its process works and whether it could be improved. Mr Houston retains primary responsibility for all children’s home claims. The Secretary for Personnel handles abuse claims involving soldiers and officers in all other settings.

All children’s homes claims, whether from a survivor or their lawyer, are directed to Mr Houston. They are often accompanied by a request for records. Mr Houston said he tried to respond to these requests before organising a face-to-face meeting. He told us that in-person interviews were a crucial part of the claims process because they allowed for a more empathetic approach towards the survivor, and also helped him verify the claim. A Salvation Army officer occasionally accompanied him to these meetings, and until 2011 would always wear their uniform. This was discontinued when it became clear the mere sight of a Salvation Army uniform could be disconcerting, even traumatic, for some survivors.

The Salvation Army accepted that as long as it was still able to hear the experiences of the survivor, a face-to-face interview may not be as part of their claims redress process, as it can be unnecessarily traumatising. The Salvation Army acknowledged that more flexibility is required in this area: while a face-to-face interview is welcomed by some survivors, others may find it difficult.

After the interview, Mr Houston told us that he verified that the survivor and alleged perpetrator were at the home at the time alleged. Mr Houston gave evidence that The Salvation Army’s approach was to “largely accept the allegations at face value, but to seek to verify and corroborate what was said”. In the early years, he sought advice from The Salvation Army’s insurer or lawyers, but since then he had come to his own conclusions about the accuracy.

Mr Houston then provided the survivor with a formal response. This usually included an apology and a settlement offer. Some negotiation over the settlement amount may follow and, if it was accepted, the offer is documented and a discharge is signed. Mr Houston said he now settles most claims within two to three months, although 12 per cent of the overall redress claims settled with The Salvation Army took longer than 18 months to settle. According to The Salvation Army, claims that took longer tended to be claims made in the early period of the claims process being adopted. The Salvation Army told us that delays occurred for any numbers of additional reasons, including that the survivor did not feel ready to go through the process, had lost touch with their lawyer or The Salvation Army, or had not come back to continue the process until a later date. The Salvation Army has never insisted survivors keep the terms of their settlement confidential.

As at 1 August 2020, The Salvation Army had settled 166 of the 238 children’s homes claims it had received. Ten claims had been declined, there was ‘no further action’ on 60 of the claims, and there were two claims outstanding. Since then, Mr Houston has reviewed several of the claims that were first declined, and four have since been settled.

The Salvation Army does not actively monitor Mr Houston’s workload or supervise his work on redress matters. The Salvation Army gave evidence that they provided “whatever resource [Mr Houston] has needed to undertake this very challenging work”. Mr Houston also provides high-level reporting on some matters, such as estimated annual payment amounts. The Salvation Army has not provided training in tikanga Māori or how to deal with survivors of abuse – a significant defect given so much responsibility rests on his shoulders. Cooper Legal has raised concerns about Mr Houston’s workload with The Salvation Army on a number of occasions. Mr Houston told us that he did not have concerns about his workload.

Some survivors told us that The Salvation Army’s redress process can lack empathy. Some said they found the face-to-face interviews difficult, and one survivor met Mr Houston at a McDonalds to receive his settlement offer.

The Salvation Army had no documented process for dealing with abuse claims. Prior to our faith-based redress hearing in March 2021, it had not published any information about its claims process on its website. The information currently on the website is under a tab called ‘Royal Commission’ and is difficult to locate.

Mr Houston has a high degree of discretion over the outcome of claims and is under no restrictions on the size of payments he can offer. He told us he did not use any matrix or criteria to help determine monetary payments, but that he considers a number of factors, including individual circumstances of the survivor (including nature and severity of abuse), legal considerations and parity between survivors. Mr Houston also said he was guided by the recommendations of lawyers acting for the survivor. He also used his experience to arrive at a settlement amount.

The average payment over the past 17 years was about $29,000, although payments ranged from $5,000 to $91,000. During that period, The Salvation Army had paid about $5 million to survivors. This figure included lump sum payments and contributions to counselling, legal fees and other services.

The Salvation Army said it regularly offered counselling to survivors, but the overall amount spent on counselling was relatively low. It did not offer a fixed sum for counselling, but rather an amount that varied according to each survivor’s circumstances. The Salvation Army has no written protocol on how survivors can get independent legal advice. It encourages those without a lawyer to seek legal advice before signing a settlement agreement. Mr Houston told us he accepted that, had this approach been in place in earlier years, it would have made a significant difference to those who settled and did not receive a contribution.

The Salvation Army has provided some survivors with support other than money or counselling, including targeted payments toward things such as hearing aids, travel for whānau, tattoo removal and a laptop, as well as providing support for a survivor to get a flat and furniture on release from prison. It has also assisted some survivors’ attendance at Salvation Army programmes, including the prison reintegration service. In questioning, Mr Houston recalled two instances of referrals being made to the prison reintegration service. While The Salvation Army also has available non-monetary supports, this has generally been provided at the request of survivors, rather than being proactively offered by The Salvation Army. Some survivors may have been unaware of this option.

In spite of The Salvation Army’s role in providing social and welfare services, it has made little attempt to utilise this expertise and resource to provide this sort of wrap around support that some survivors badly need. Its dealings with survivors have been kept separate from the very services they could have benefitted from. The Salvation Army has committed to do better in this regard.

Mr Houston said apologies were an essential component of any redress package, although he acknowledged that early attempts at apologies were inadequate. He said today’s apologies were more empathetic and less legalistic. Some survivors have reported being pleased with their apologies, although some survivors have still criticised the apologies they received as insufficient.

The Salvation Army does not have a policy on dealing with claims brought by the whānau of a deceased person, or by individuals who died before their claim was settled. Mr Houston said he considered such claims on a case-by-case basis. He said it was difficult to assess claims brought on behalf of deceased individuals using the existing process.

Where allegations were of possible criminal conduct, Mr Houston gave evidence that The Salvation Army encouraged the survivor to contact Police and report the allegations. The Salvation Army would cooperate fully with Police if a complaint was made, but The Salvation Army would not approach Police without the survivor’s consent. While we heard evidence of The Salvation Army’s cooperation with Police, we also heard that Mr N was not proactively offered support to make a criminal complaint.

Mr Houston did not collect data about whether survivors had any disability. While Mr Houston would tailor the process to survivor needs if he was asked by the survivor, he would not proactively seek to do this. Mr Houston has not had any training in working with disabled people.

The Salvation Army has not taken a proactive approach to finding survivors of abuse. There has been a limited number of Pacific claimants that have gone through the redress process. When asked whether The Salvation Army would proactively seek out survivors to inform them about the process, Colonel Walker stated that they had translated “a considerable amount of our information in different languages”, and that engaging appropriately and clearly with people of different cultures is a “journey” that The Salvation Army is on. Murray Houston said that The Salvation Army would look at any opportunity for accommodating persons with disability to come forward but has not proactively sought out disabled survivors. Colonel Walker said that he expects The Salvation Army’s redress process to enable supported and informed decision making for disabled survivors going forwards. It is unclear whether The Salvation Army intends to make information available in New Zealand sign language or easy read formats.

Failure to honour commitment to Māori survivors

Colonel Gerry Walker stated that The Salvation Army is “very conscious of our responsibilities and obligations under the Treaty of Waitangi”. As early as 1997, The Salvation Army had a Treaty of Waitangi policy that recognised the importance of bicultural partnership. Despite having policies on te Tiriti, The Salvation Army failed to incorporate them into its redress process in a meaningful and comprehensive way. The Salvation Army did not proactively incorporate tikanga Māori or te ao Māori values into its redress process.

Murray Houston said he had not received any training on tikanga Māori and accepted that such training “would have been helpful” in fulfilling his role. Mr Houston did not collect data about survivors’ ethnicity. He did not incorporate tikanga Māori into his assessment process, unless specifically requested by the survivor, and generally did not tailor the process to survivors’ different cultural needs – although he tried to support survivors with different needs, and from different backgrounds, as best he could. In one instance, Mr Houston received a claim where a survivor spoke to a loss of cultural identity. Mr Houston brought a Māori cadet with him to the meeting, which was well received by the survivor.