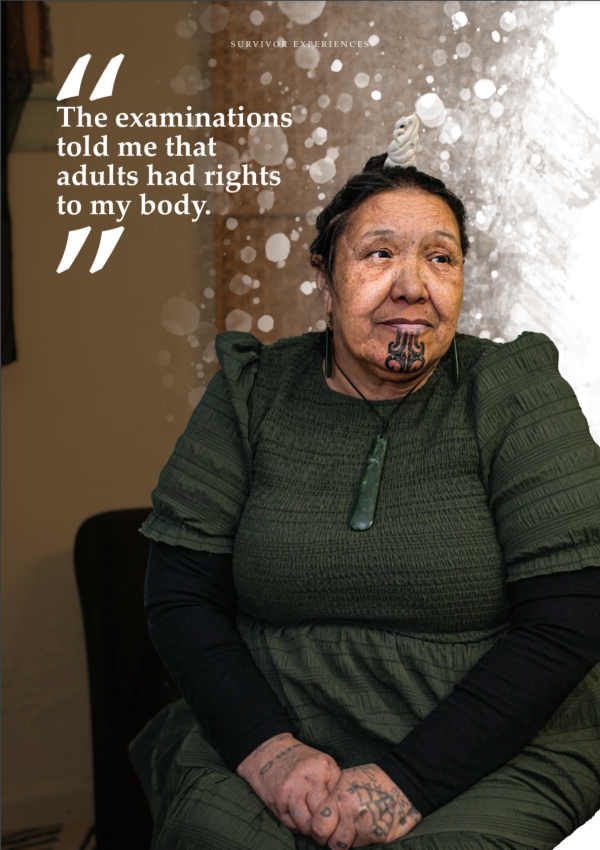

Survivor experience: Gwyneth Beard (also know as Piwi) Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Age when entered care: 11 years old

Year of birth: 1961

Hometown: Ōtautahi Christchurch

Time in care: 1972 –1978

Type of care facility: Girls’ homes – Strathmore Girls’ Home in Ōtautahi Christchurch, Kingslea Girls’ Home in Ōtautahi Christchurch, Weymouth Girls’ Home in Tāmaki Makaurau

Auckland.

Ethnicity: Māori (Ngāti Porou), Welsh descent

Whānau background: Gwyneth has three older sisters and one older brother, and three younger

brothers.

Currently: Gwyneth has given birth to seven beautiful children, five who are alive, and 36 mokopuna. When she was 30, she lost her son to cot death. In 2011 one of her daughters passed away; Gwyneth is now raising three of her mokopuna. There is neuro diversity within the wider family and Gwyneth believes she may have an undiagnosed neuro diverse condition.

I was a very damaged child, and to survive I became quite rebellious. Between the ages of five and about eight or nine, I was sexually abused by someone who knew my family. It carried on for a long time, and I didn’t feel like I could tell anyone – I would have gotten the blame for it.

My mum put me into social welfare care.

She took me to Strathmore Girls’ Home. I’d never been to a place like it. A staff member took me to a cupboard-like room, and I was given rompers to wear and some knickers. It was frightening and foreign. After I was let out of the cells two older girls sexually abused me and raped me, as an initiation. They held me down and they laughed.

I experienced several forms of abuse at Strathmore But the worst thing about Strathmore was the medical examinations. Every time you left the institution and came back, you had to have one, even if you were just on day leave.

The first time I went in, I had no idea what was going on. It was worse than sexual abuse. You could hear them saying things about you while you lay there, helpless. There was a male doctor and a female staff member, and she would hold me down. If you moved at all, she put straps on your legs where the stirrups were so you couldn’t move. I always had the straps.

Then the doctor would insert a big steel thing inside you.

They said the medical examinations were to check for sexual diseases. I remember a comment they made that I wasn’t a virgin, that I was sexually active. That really buggered with my mind, that these adults were blaming me for the sexual abuse I’d experienced. Nobody thought to ask why, or to find out what had happened to me.

No one should have to go through that experience, especially after being sexually abused. It was absolutely horrific.

Every girl in Strathmore had to have the medical examinations. We would say we had our periods so we didn’t have to undergo the examinations, and they’d make us show evidence of our period. So when we did have our periods, we’d hide the evidence, so that when it came to test day we had something to show.

A new doctor arrived in 1977, called Dr Morgan Fahey. I had two examinations done by him.

When I look back now, I understand what was going on – he was touching parts of my body that he shouldn’t have touched. I know it was wrong. He’d say things like “I’ll just put some lubrication in” – you don’t need to lubricate for that.

The other doctor did the same.

When they put the lubrication in they used their fingers, always two fingers. It wasn’t until years later that I learned it wasn’t a necessary part of the procedure.

Dr Fahey did other things that were different. He touched you in places he didn’t need to – he’d touch my clitoris during the exam, and he would give you an examination like when you’re having a baby to check you’re dilated. I know the other girls got the same examination.

Later on, when I heard about Dr Fahey being charged, I put everything together and realised the medical examinations at Strathmore were very wrong. You shouldn’t do that to 12 year olds.

The staff at Strathmore were mainly Pākehā – there were no Māori staff, although there were a lot of Māori and Pacific children at Strathmore. Staff picked on me for being Māori - we were seen more as ‘the trouble’. I remember hearing the words ‘typical Māori’ quite often from staff members. Were the Māori girls more naughty, or was it just that we felt we were naughtier because we were made to feel that way?

I turned my life around at Strathmore, and I was told I was doing well.

One day I thought I was going home, only I got in the car to discover they were taking me to Kingslea. I couldn’t understand why I wasn’t being rescued from the situation I was in.

I was at Kingslea for around three days before I ran away. I spent a lot of time in secure.

Children should not be locked up. You would not be locked up in your own house, so why should the Government be allowed to lock you up in a cell for weeks on end?

I ended up being the longest person held in secure at Kingslea at that time. I was an at-risk person, so the only place they could hold me was secure.

Dad went back to Wales for a while because his mother was sick. When he came back and found out I was in a home, he fought to get me out.

They were just waiting for me to be able to go to Weymouth.

By the time I got there, I could handle myself. I’d adapted to institutional life and I wasn’t picked on by anyone. Weymouth was a better place for me than Kingslea and Strathmore, although the secure unit was horrible, worse than any other secures I’d been in – it was more like a police cell. It smelled of kerosene, and the toilet was in the cell, which wasn’t nice.

There was an article about me and Weymouth in a magazine. It had a photo of me from behind and said I was the highest absconder in New Zealand or something. I wasn’t a monster to be locked up.

I also still had to undergo medical examinations at Weymouth. They were done by a nurse, who was lovely, but I always pretended I had my period.

The first time I ever properly thought about suicide was when I was at Kingslea. I thought everything was my fault. I didn’t understand what was going on with me and what I’d done wrong. I thought out what I was going to do, how I was going to do it. I don’t know why I didn’t do it, but I’m so glad somewhere in there, one of my tupuna made me strong enough not to go through with it.

After Weymouth, I was sent home, and things didn’t work out well for me there. I was institutionalised, so I felt I couldn’t live outside of the homes. I just didn’t know how to focus or function. All I knew was dysfunction, and I just wanted revenge for my life, so I didn’t last long at home. I went back to Strathmore on my own. I knocked on the door and said I had nowhere else to go.

When I left State care, I was given $21 by the State, and I was on my own.

The abuse I suffered in care was so traumatising, it still affects me today.

I’ve struggled to go for smear tests because of the medical examinations I experienced in care. I’ve had cancer scares. I was traumatised by those experiences. The examinations told me that adults had rights to my body, no matter who they were, and that’s wrong.

I’m now a social worker, and I work under the kaupapa of Tūpono te mana kaha o te whānau, which means to stand in the truth and strength of the family. I want to make sure that children who go into care don’t come out more damaged than before they went in. I believe in care and protection, but it needs to be care and protection, not care and damage.

We live in a society that punishes the child for adults’ behaviour, and we need to find a system that fixes that.

We also need to decolonise the way we think within our government departments, and we need to come back to Tikanga Māori and the Treaty of Waitangi. We need to come back to whanaungatanga, manaakitanga and those concepts, to bring it all together and ask, how is this going to work for this whānau?

Later in life I started to have this ability to talk to myself. I think it’s my tīpuna. My tīpuna that stand beside me, giving me this ability to focus. The way I have done it, is I think what I would tell someone else, then I tell myself that. I get told I’m a wise old lady, but I get that strength from one of my two tīpuna. This wise old lady that stands beside me gives me all this wisdom.

Source

Witness statement, Gwyneth Beard (26 March 2023).