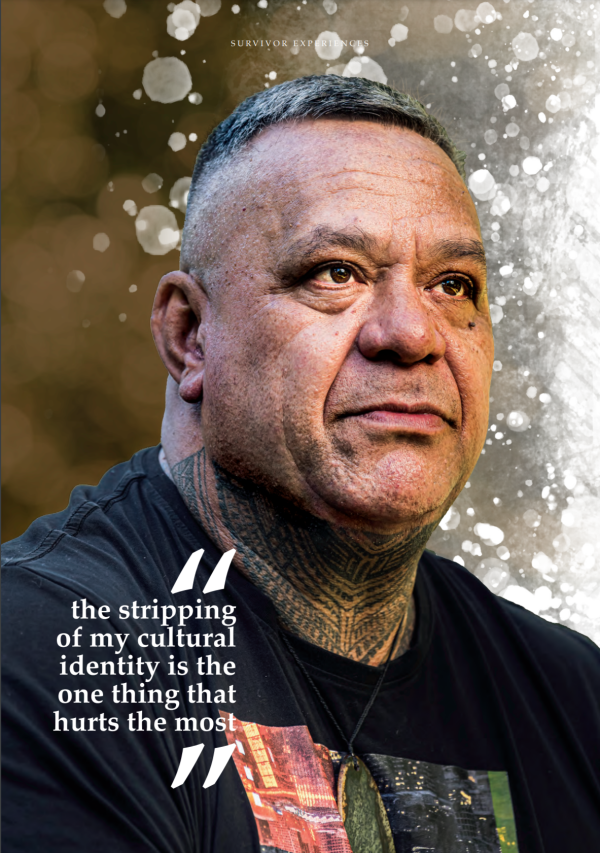

Survivor experience: David Crichton Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Age when entered care: 1 year old

Year of birth: 1967

Hometown: Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington

Time in care: 18 years

Type of care facility: Children’s Homes – St Barnabas Home, Salvation Army Residential Nursery, Berhampore Children’s Home, Our Lady’s Home of Compassion, Epuni Boys’ Home. Foster placements, including a foster placement where he was relocated to Papua New Guinea; Open Home Foundation.

Ethnicity: Samoan

Whānau background: David’s mother was born in Dunedin, he is her youngest child. David was raised under the name Mohi and grew up believing he was Māori. On getting his file at 30 years old, he read he was in fact Samoan and learnt his father’s name, noted in his file. His dad was Samoan, but David didn’t get to meet him before he passed when David was 15. No one connected David to his family during his time in care.

Currently: David maintains a strong connection to the Māori side of his upbringing as this formed a big part of his identity growing up, alongside being Samoan and is continuing to learn what this means. He has connected with his Samoan family and carries the surname of his father. He has a supportive and loving partner, children and moko, who have learnt a lot about understanding David’s trauma.

I went into care as a baby and spent my entire childhood and teenage years in care.

At birth I was named David James Mohi. Throughout my time in care, I was told I was Māori. I was referred to by others as Māori. I believed I was Māori.

I am not.

It was only after I requested my care files when my partner and I were expecting our first child that I found out my biological father was a Samoan man named James (Jim) Crichton and that I am of Samoan heritage. By this time, I had claimed the Māori culture I thought was my own and carried Māori tattoos all over my body.

Presbyterian Support Central and the State knew from the very beginning that Jim Crichton was my dad, and that I was of Samoan heritage. It is there in my files, in black and white.

My records show that my mum had significant mental health issues. She was not well, and Presbyterian Support Central and the State knew this. They shouldn’t have relied on information provided by her given her mental state.

My records state that a major source of conflict for my mum was that my father was Samoan, that she despised him for being Samoan and thought Samoans were inferior. She was reported to consider herself to be superior in every way to my father and felt that by living with a Samoan she had degraded herself.

A social worker made an entry shortly after I was born: “The baby’s father is an Islander and this coupled with Mrs Mohi’s low intelligence would probably make adoptive placement for the baby rather doubtful.”

My birth certificate doesn’t record Jim Crichton as my father – it says my father was unknown. But my mother knew who my father was. She kept his name off my birth certificate intentionally.

My father’s sister, Aunty Rose, is mentioned in the early reports. But no one made attempts to contact her directly. The social workers believed all the negative things my mother told them about my dad and my family, despite references in the report to my mum being “disturbed” and information provided by her lacking credibility.

My mother gave me the surname Mohi. I think this was probably so that the Crichton family couldn’t ever find me, I will never know.

The obligation on the State to establish, preserve and strengthen a relationship between me and my paternal family was further heightened because they knew my mother had such strong feelings against my Samoan father, family and heritage. They knew she was very unwell. There was no way she was going to support and encourage any relationship between me and my family, so when Presbyterian Support Central and the State became involved in my life and responsible for my care that duty fell squarely on them.

My dad died while I was in the care. My mother knew for ages that he had been sick. He died on a Monday. I understand that the previous Friday, the staff at my placement became aware that my dad was in hospital, he was likely to pass away and he had asked to see me. But the staff kept this information from me until Sunday. On Monday morning the staff contacted the hospital to organise a time for me to visit him, but they were told he had died a few hours earlier.

Later that week my mother and a social worker took me to my dad’s funeral. I had no idea what was going on. At the funeral my mother told my dad’s family that Jim was my father. She introduced me to people by saying things like, “This is Jim’s boy”. I vividly remember family members staring in disbelief, some didn’t know how to take it, which made me feel very uncomfortable. I was only there for a very short time, less than half an hour. It was so confusing for me.

Despite the other abuse I suffered in care, the loss of my cultural identity is the part of my experience in care that hurts me the most. I spent all my childhood, youth and the beginning of my adult life believing that I was Māori. I was denied any knowledge of my Samoan family, culture and identity. I am covered in Māori tattoos because I believed that that was who I was. If I had truly known of my Samoan cultural heritage I would likely be covered in Samoan tatau.

It took many years, and I still struggle with it, to accept that I’m Samoan, because I wasn’t raised as a Samoan, but all my family is. With my Māori family and friends, I’m very culturally comfortable, they are staunch people of Māori descent, and they would be the first to say that I’m Māori.

I feel like I was Māori before I was Samoan and when I’m around my friends I still feel like I’m Māori. Adjusting to the Samoan culture has been challenging. The way things are done is quite structured and there is a hierarchy of who can say and do different things. I am quite a vocal person, so I have had to adjust that to fit into the Samoan way of doing things.

When children are in care, they need to be made aware of their ethnicity, their true identity and of their extended family. When Presbyterian Support Central and the State became responsible for my care, they should have done all they could to locate my dad and my paternal family directly, but they did not. My Samoan family lived in the Wellington region, and it would not have been that hard to find them.

I missed out on having relationships with my extended family because of my mother’s secretiveness and because Presbyterian Support Central and the State neglected their duties. I believe that the organisations responsible for my care had a duty to at least tell me who my family was, to tell me about my ethnicity, to make genuine efforts to look for my family. This responsibility increases, in cases like mine, where a child spends their whole upbringing in care.

After I gave evidence at one of the Inquiry’s public hearings, Presbyterian Support Central’s chief executive wrote to me to apologise for the abuse I suffered while in its care and to acknowledge my evidence. My family and I found this to be a genuine apology and we later met with senior staff face-to-face. We appreciated this.

My children very much identify with Samoan and Māori culture. They have been around their Samoan family their whole lives, and due to this have a strong connection to being Samoan. At times I feel guilty and angry about not being able to teach them about my family and the Samoan culture, but it has been great to learn things together and to build bonds with our Crichton whānau in the process.

It’s been a joy to see my children’s desire to be connected to who they are. Seeing my daughter building connections online with the extended Crichton family and hearing my 16-year-old son’s speech in the Samoan language are great successes for us as an aiga.

There are no words that will ever come close to fully describing the impact this has had on me. I suffered all forms of abuse during my time in care, but the stripping of my cultural identity is the one thing that hurts the most and has had the most effect on me and my family. This is the main reason why I am sharing my story with the Inquiry in the hopes that no other child goes through what I have.

Source

Witness statement, David Crichton (9 July 2021)