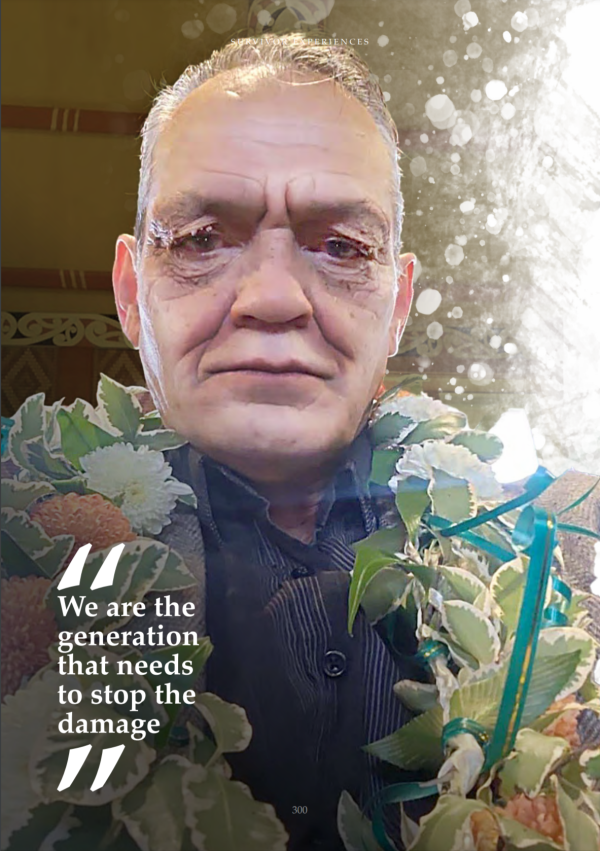

Survivor experience: Toni Jarvis Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Age when entered care: Adopted at 10 days old; entered a family home aged 7 years old

Year of birth: 1961

Type of care facility: Adoption; family home – Awatea Street Family Home, Trent Street Family Home; psychiatric hospital – Cherry Farm; boys’ homes – Epuni Boys’ Home, Hokio Beach School, Holdsworth School; borstal – Invercargill Borstal.

Ethnicity: Māori (Ngāti Toa, Ngāpuhi) and Pākehā

Whānau background: Toni’s parents had a casual relationship, and Toni was adopted 10 days after his birth as his biological mother didn’t have support to raise him. His adoption order was overturned in 2003 as it was illegal – it was arranged before he was born by a social worker and Toni’s mother wasn’t aware it was happening. His adoptive family had two children, one older than Toni and one younger.

There was a lot of violence and abuse in my house when I was little. I used to wander the streets at a preschool age looking for toys and stimulation. I didn’t get fed much so I’d steal food.

A social worker visited me and found me beaten black and blue. I didn’t think this violence was abnormal – I didn’t know any different. I started to run away from home and Social Welfare got more involved. I went to a family home when I was about 7 or 8 years old, then after I turned 9 years old, I went to Cherry Farm. One of the doctors advised Social Welfare that they didn’t have the facilities for a 9-year-old boy and that I would be placed in a locked facility with the adult patients, that the adults would corrupt me and the facility wasn’t made for children. Social Welfare sent me there anyway. Social Welfare had the attitude of doing what they wanted, and not what was best, throughout my childhood.

I didn’t know what Cherry Farm was, and I didn’t have any understanding of why I was taken there. I was excited to go to a cherry farm – all I could think about was the tins of fruit salad, where there would only be one cherry. My siblings and I always fought for the cherry, and I was excited that I was now going to a farm of them.

Cherry Farm was a transit place for me until there was a spot at Hokio Beach School. I can’t understand how the State could expect me to go to Cherry Farm and then later on manage to fit back into the community.

I entered the locked main area and it was like, welcome to the horror show, for a 9-year-old boy. The patients were very disturbed and mentally unwell, making noises, wailing, and making unusual movements. I thought, “what the hell is this” and I was still wondering where the cherries were. I went into a corner and got into the foetal position.

A door opened and an older man came in, shuffling towards me with his pyjamas around his ankles. He had a handful of shit and was eating it. He rubbed the poo on my face and head. I was screaming, but no one came. One of the other patients was masturbating and he ejaculated all over me in the corner. I was covered in shit and semen.

My bedroom was a cell with a slot for them to look in. I screamed, and they sedated me with Melleril. I had no mental health diagnosis, no assessment, and no understanding of why I was there.

Some of the patients were normal and could have a conversation. I was initially drawn to one of them as he played the guitar. He asked me to sit on his knee, and he bounced me around, then put his hands down my pants and his fingers up my anus. I threw billiard balls at him and was locked in a room for a few days for doing that. I screamed constantly to try to get out. I started to lose my sense of sanity. They regularly medicated me and I became quite docile.

I was constantly medicated after that, and the patients then had free reign to me. I was sexually abused at least six times when I went to the toilet. Groups of men would insert their fingers in my anus and grab my penis. I would urinate in my pyjamas so I didn’t have to go to the toilet.

I was discharged from Cherry Farm after about six weeks, and went to Epuni Boys’ Home then Hokio Beach School. The boys checked me out as the new boy, put me on a grey blanket and pulled me along the polished wooden floor. I thought this was fun until I got to the end of the hall. They swung me into the wall and pulled the blanket over my head, then started booting me. I went from being okay being there to complete fear.

I was regularly abused by a boy who was the kingpin, but it wasn’t only him – some nights when the night watchman left my room, I could count the seconds before three or four boys would rape me. Initially I used to fight and squeeze my buttocks tight, then I just became a rag doll. As soon as the watchman did his check, I’d spit on my hand and wet my anus, and lie with my pants down – that way it hurt less.

I wasn’t sexually assaulted by any of the staff, but I didn’t feel like I could talk to anyone about the abuse. Lots of the other boys were also survivors of abuse and they were angry. The abuse was often just passed down the food chain. The culture at Hokio was to shut your mouth and not complain.

I believe I was in Hokio for just under a year, but my time there seemed like an eternity. I can’t say how many times I was raped while I was there, but my guess is about 200 times.

I went to the Awatea Street Family Home next and it was a good experience, but after about six months, the kingpin from Hokio arrived. He was only there for two days before the abuse started. He continued to abuse me there, about 30 times over the next five or six months. I didn’t tell anyone – I was threatened and scared. I stole a bike and smashed it up, because I knew they’d take me away, and I wanted to get away from him.

I went to Holdsworth School next. The deputy principal would come around the dorm at night and kiss us on the lips – full and sloppy. He would then fondle us including putting his fingers in our anuses. I had been raped so many times I was conditioned to it, so it was the kiss that I found the most disgusting. Two other staff members were abusive when I was there, and some of the other boys. It was well ingrained in me by this stage to shut my mouth.

I ended up in Invercargill Borstal and later Paparua Prison in Christchurch. A lot of borstal and State care boys were also in prison. I changed a bit after I got out of prison, and I haven’t been back to jail for 40 years since then. I still have a lot of issues and problems with violence, but I turned away from the life of crime that would have kept me behind bars.

I didn’t know what a relationship was. I often ran away from relationships. I didn’t know how to be intimate – I was used to being beaten and sodomised. Feelings of abandonment have never been far from the surface. I used alcohol as a coping strategy, but I stopped drinking to excess about 20 years ago.

I found out I was adopted when I was 19, and life started to make a lot more sense once I knew that. I’ve always questioned my identity. I struggle with it, because if I don’t know who I am, then who are my children, my tamariki, my mokopuna.

My mental health was definitely impacted by my time in care. I struggled with depression but I didn’t let it show. I was beaten until I’d stop crying, so I didn’t cry for 30-odd years. I’d shut things out.

I believe we should receive an unreserved apology from the Crown for the abuse we suffered while in the care of the State, an admission of fault and a starting point for moving forward. Abuse can be prevented by getting rid of State institutions. The boys’ homes were breeding grounds for abuse. It’s gone on for too many generations. You can’t care for children in institutional systems – kids need one-on-one love, encouragement and acceptance.

I’ve spent 44 years of my life looking for justice and answers. It’s time for the State to be honest, stop the lies and deceit. I want the State to bring out all of the records, be honest, and put them on the table for all to see. This is a chance for real change, with the truth.

We are the generation that needs to stop the damage.

Source

Witness statement of Toni Jarvis (12 April 2021).