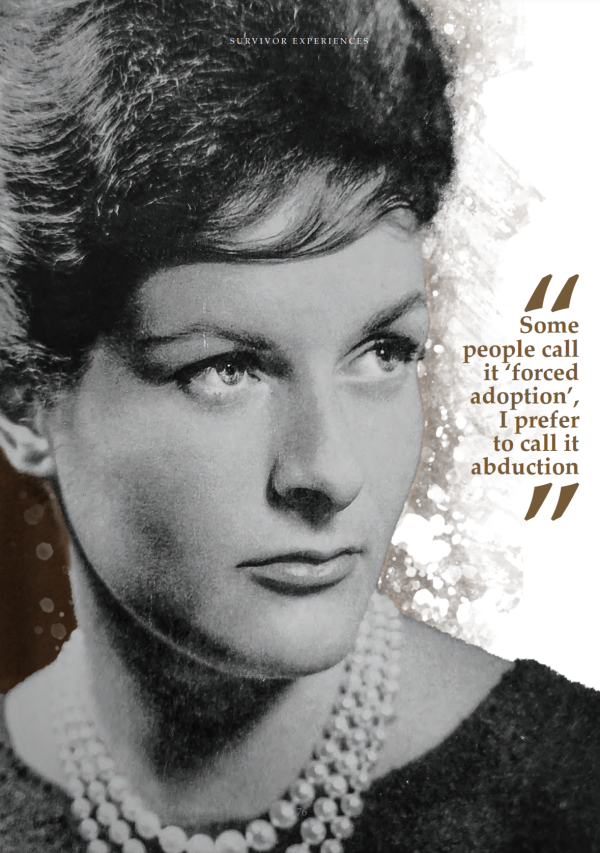

Survivor experience: Maggie Wilkinson Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Age when entered care: 19 years old

Year of birth: 1944

Hometown: Gisborne

Time in care: January to June 1964

Type of care facility: St Mary’s Home for Unwed Mothers

Ethnicity: Pākehā

Whānau background: Maggie grew up in Whakatane.

Currently: After a period living in Australia, where she met her husband Graeme, Maggie now lives with her family in Gisborne. She was reunited with her daughter Vivienne 18 years after being forced to give her up for adoption.

My child was taken away by a self-righteous matron. She was abducted from me at birth then given away to make strangers happy. No one bothered to look back at the grief of the ‘sacrificing’ mother.

In 1964 I fell pregnant with my first child. I was 19 years old. The father of my baby refused to marry me and joined the army, where he volunteered to be posted to Vietnam.

I was in Whakatane living with my family. They were ashamed and didn’t want to tell anyone that I was pregnant out of wedlock. They made me stay in my room and out of sight – I couldn’t leave the house and had to stay hidden from the community.

They wouldn’t take me to see our family general practitioner, because they wanted to hide my secret. Instead, they arranged for another local doctor to come to the house and discuss how I was to proceed with my pregnancy. This doctor advised my family to send me to St Mary’s Home for Unwed Mothers in Ōtāhuhu, Auckland.

He described St Mary’s as a safe haven, a sanctuary, and told them I would be cared for at the home. But it was neither a haven nor a sanctuary.

St Mary’s public-facing areas were nice, such as the office and the maternity wing for married women, and they gave the impression that it was a good place. There was a birthing suite and public maternity hospital on the premises where we gave birth to our babies.

The rest of the home resembled a concentration camp. It was bare, with very little furniture, and we slept in dormitories. The home was always damp because of the constant wet mopping.

There was an orphanage, full of the ‘unadoptable babies’, who were mainly twins and Māori children or children of mixed race. It was a disgusting place, always cold, and we weren’t allowed to play with the children, although they were crying out for attention.

The home was run by Matron Rhoda Gallagher. At first, she seemed to have my interests at heart and created the appearance in front of my parents that she would look after and care for me. However, it was soon clear that the matron’s ‘homey’ front room did not mirror the hell hole out the back.

Matron was a vicious woman who would always shout at us and say the most awful things to us. She would tell us that we were fallen women and that she would make decent women out of us. She used words such as selfish, used, tarnished and illegitimate. She would tell us that we were selfish to want to keep our children, and she would refer to our babies as her babies. She would say things such as, “someone better than you wants your baby” and “there are lovely married couples just wanting to give baby a home”.

We all had to take Matron’s surname and we could not use our own given names. First names were changed and surnames disappeared. We wore communal clothes from a shared box of clothing – we were only allowed to wear our own clothes on a Sunday if a visitor was coming. When I look back on this, I see that the process of institutionalisation was instant, and we were dehumanised.

There would have been between 18 to 22 unwed women at St Mary’s at any one time, including young pregnant girls in the home. They were told to say they were 16 years old if anyone asked them. We were made to attend chapel twice a day for our sins. I recall one time another one of the unwed mothers fainted in chapel and Matron told us to just leave her there on the floor.

We were treated as the proverbial dirty girls and were punished daily with a heavy work schedule. I worked hard in the kitchen, orphanage and laundry. I cleaned and wet mopped constantly, I bottled produce from the harvest festivals. The work was relentless and only with very basic equipment and tools, even when we were heavily pregnant. This was unpaid labour and the conditions were something out of a Charles Dickens novel.

As a single mother, I qualified for a sickness benefit from the government, which was paid directly to the home. I was allowed a small amount of pocket money per week from that, enough for a packet of barley sugars and some wool. We were effectively locked up in the house and not allowed to go anywhere. For most of us there, the ‘home’ was a prison for sad girls with no choices and no advocacy. It was a place of fear and punishment.

Food was scarce; we weren’t given enough to eat because Matron wanted us to have small babies so there were no problems during delivery. I was not given any education about pregnancy or what our births would be like – Matron did not allow or give any opportunity for advice from anyone. Letters were vetted by Matron, coming into or leaving the home. This meant that we were isolated and controlled by her.

Social workers were meant to visit the home, but they were frightened off by Matron. I was told this by an ex-social worker, who is now deceased – he apologised to me and told me that they knew terrible things were going on at St Mary’s, but they did nothing.

It became very apparent quite early on that we would be forced to have our babies adopted. I was horrified and distressed. There was a Pacific Island woman who worked in the kitchen at St Mary’s and she looked after her daughter living on site. I loathed St Mary’s but to keep my child I thought that I might be able to live and work there just like her. When I spoke to Matron about this idea she seemed supportive and agreed to my request.

However, she had no intent on following through. When my mother visited, Matron told her that I was not the type to cope with a child.

I got in trouble one day and was placed into an isolation room and given some sort of medication to bring on the birth. It was a difficult delivery and I was torn to bits inside. I was left in a physical mess with no post-natal treatment or support. A nurse let my baby stay in the room with me for a short time and I placed my hand on my daughter as she slept. This was a big deal as the nurse wasn’t allowed to do this and would have been in trouble if Matron had caught her. While I was asleep my baby was abducted by Matron and concealed from me.

I was drugged without consent – I was given medication to stop lactation. My breasts were also bound tightly. My baby was given to an Anglican woman who was a member of the Auckland Diocese. I was called to say goodbye to my daughter when they took her, but I wasn’t allowed to hold or touch her. Eight days later I was taken to a lawyer’s office, where I was made to sign documents and swear on the Bible that I would never try to find my daughter.

I did not want to sign but felt that I had to. It is recognised that consent not freely given is not consent at all. Adoption corruption in New Zealand relied on invalid consents obtained under pressure, and on manipulation, threats, illegal practices, emotional blackmail and stand-over tactics.

I was discharged from St Mary’s two weeks after the birth, bleeding, both physically and mentally. I was told by Matron that I would get back to my normal life and I would forget about my daughter. This has never been the case.

For all these years, I have been grappling with the ongoing grief and depression. My husband has stood by me, my sturdiest support. My children from my marriage lived with a mother who was deeply depressed and suicidal.

Those on the gravy train of adoption practiced a culture of total power over unwed mothers in order to supply the adoption industry.

They are guilty of the traumatic act of removing newborns from their mothers, guilty of ignoring pleas of the mother, guilty of rendering the mother incapable of taking any action in a world that ignored her, guilty of concealing baby and coercing mother to surrender her child. They have a responsibility to make reparations and apologise. The adoption legislation enabled those with the agenda of wielding power to exert their beliefs of moral judgement over those they considered had sinned.

It is time that the State- and faith-based regimes of abuse be acknowledged without the excuses and the dismissive attempt to annihilate our physical being and pain with “but that’s just what happened then” or “it’s not like that anymore”.

Source

Witness statement, Margaret Wilkinson (7 September 2020)