Survivor experience: Rūpene Amato Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Age when entered care: 11 years old

Year of birth: 1972

Hometown: Wairoa

Type of care facility: Education – St Joseph’s School, Wairoa

Ethnicity: Māori (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngā Ariki Kaipūtahi, Ngāti Māroko) and Samoan

Whānau background: Rūpene lived with his Mum and Dad, three brothers and two sisters. Rūpene’s eldest brother passed away in the 1990s during a rugby game. His death really took a toll on the family and many are still struggling with his passing today.

My father is full Samoan. My mother is Māori. Before Mum and Dad got married, Dad had to seek approval from Mum’s family. My Mum’s family weren’t supportive of their relationship because Dad was an Islander. In Wairoa at the time, it was out of the norm for a Māori person to marry an Islander, but it was normal for Māori to marry Palagi people.

Mum’s family became more accepting of Dad over time. However, during my childhood, Dad continued to be teased and bullied by Mum’s family about being an Islander. Because of this, I think Dad chose to be more ‘Māori’.

Given we were the only Pacific Islanders in Wairoa at the time, me and my siblings identified as Māori because we knew the other kids would hassle us if we said we were Samoan. We were also closer to our Māori whānau growing up because our mother raised us Māori, and Dad chose to conform to the Māori way of life.

Growing up, there was a lot of alcohol use and domestic violence in our household. Dad was quite violent towards me and my siblings and our Mum. Because of the violence during our childhood, my siblings and I promised that we wouldn’t use violence against our children when we were older. I am happy that our generation has been able to fulfil this promise and give our moko a new way of doing things. Although Dad was violent towards us back then, he isn’t violent towards his moko.

My maternal grandfather was a Bishop of the Rātana Church. The Rātana faith was a big part of our whānau, marae and culture. My father is Catholic and was raised in the Catholic Church in Samoa. As a child, I attended events and church services at both the Rātana and Catholic churches in Wairoa.

My siblings and I started school at North Clyde School in Wairoa. After a few years, our parents moved us all to St Joseph’s School, which was a Catholic primary school in Wairoa. We changed schools because Dad was a Catholic. Back then, you had to be a baptised Catholic to attend St Joseph’s.

As a child, I always loved school and learning. I enjoyed it more than my siblings. In Wairoa, St Joseph’s is known as a ‘good academic school’. Because of this, my parents saw it as a blessing that we were Catholic and were able to attend the school.

Our former parish priest, Father Snowden, was an amazing man. He was a part of our community and would help whānau in need whether they were Catholic or not. We were always happy to help him – he was kind and gave us treats. In my young mind, I thought all priests would be like Father Snowden. However, that wasn’t the case.

The abuse I suffered happened when I was in form one at St Joseph’s School. I was around 11 or 12 years old at the time. A new priest was appointed to St Joseph’s parish following the death of the former priest. I can’t remember the new priest’s exact name, but me and my friends at school would call him “Fitz the feeler”.[1]

At that age, my knowledge of sex was what I had learnt from friends at school. We were given no explanation about what sex education or puberty was, and we weren’t prepared or warned about the content of the lesson with Father Fitz.

The first time I was sexually abused was by Father Fitz in the priest’s house. I remember the nun giving me a yellow slip and telling me to go see Father Fitz. I went by myself and gave him the piece of paper. He opened the note, read it and said, “Oh while you’re here, let’s have a conversation.” He then took me to the lounge at the front of the house and started talking. I can’t remember how the topic came up, but we suddenly started talking about sex.

Father Fitz then asked me to remove my shorts, which I did. At this point, I was in my underwear standing in front of the couch I was sitting on. He grabbed my penis and said, “This is your penis, you might know it as your cock.” He was stroking and masturbating me through my underwear. I remember standing there with my pants down freaking out because I had no idea what was going on. Back then, I was also exploring my own sexual identity.

Father Fitz then touched my testicles and said something like, “These are your testicles, you might know them as your balls”. While we talked about sex, Father Fitz groped and fondled me. All of the touching was through clothing. He talked about things like masturbation and ejaculation. These ‘sex education lessons’ would last about 20 minutes. Then I would be sent back to class.

By the time Father Fitz started at St Joseph’s, the way confessions were done had changed. There was no longer a partition between the priest and the parishioner. The confessions at the school were face-to-face with Father Fitz, in an open room with a few chairs. During confession, Father Fitz would grope and fondle us. The door was always closed. Afterwards, he always insisted that we hug him before we could leave. Confessions became more frequent than the sex education lessons.

One lunchtime, I remember sitting in a circle with a group of friends. Me and my friends were talking about something unrelated when we saw a student walking towards the priest’s house with a yellow note in his hand. We all said things like, “Oh I know where you’re going” and started laughing. Because we were talking about what was happening, it made other students aware of what might happen to them when they were alone with Father Fitz. There was a girl in our group who was quite well-endowed for her age. She told us Father Fitz tried to touch her breasts. Everyone then started sharing stories about abuse from Father Fitz. We all agreed to go home and tell our parents. I didn’t tell my parents that night, mostly because I wasn’t sure how they’d take it. I was scared I would get a hiding mainly because I know that it was Dad’s church. At the time, I knew that it would be my word against the church. I knew Dad would take the church’s word over mine.

I later found out that when one of my friends told her mother about Father Fitz, her mother called some of the other parents and told them what Father Fitz had been doing. A group of parents went to the school the same day and complained about Father Fitz. Within a week of this complaint, Father Fitz was no longer at St Joseph’s. We didn’t even see him the next day. There was no explanation given as to why he left. Nobody from school or the church talked to us about it. Father Fitz was just there one day and gone the next.

To this day, I’m not sure whether my parents knew about what happened with Father Fitz, or if my friend’s mother had called my Mum that night. If they did know, we never talked about it. Most Pacific families, especially Catholic, don’t talk openly about sex or sexuality.

On reflection, I now know that Father Fitz was grooming us all. We lived in a poor town and were more vulnerable to this kind of abuse. We never discussed contacting police or anything like that once Father Fitz left.

One of the major impacts on my life was that I became distant from the church as a result of what happened to me. However, more recently, I have decided to visit the church to close the chapter on my abuse.

There should have been further consequences for Father Fitz. I believe that he should have been prosecuted for what he did. Following on from the abuse, the school should have had someone speak to us about what had happened, what was done about it and how to get support if we needed anything. However, the school didn’t do any of this.

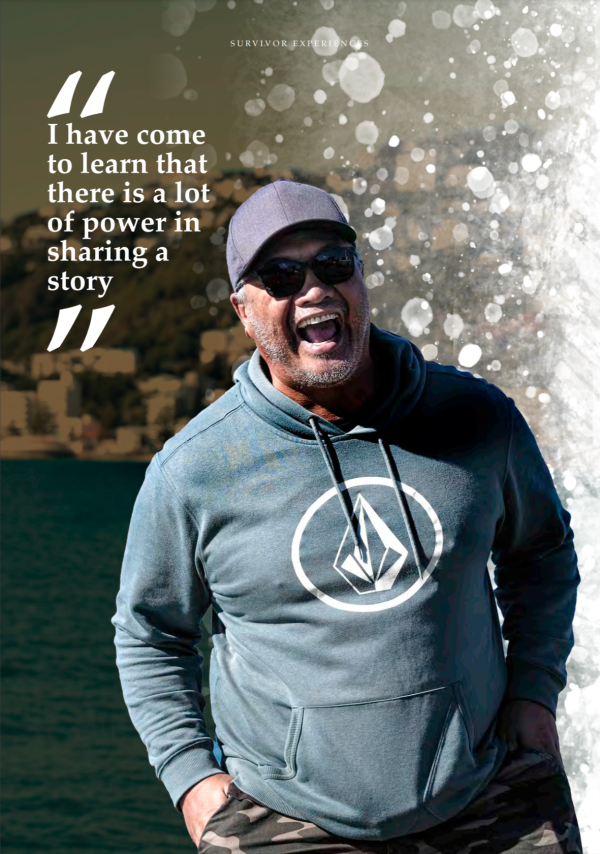

I have come to learn that there is a lot of power in sharing a story. Particularly for those who are survivors of sexual abuse who feel that they are alone. It would be great if it were normalised to have someone like myself or other survivors who work in these fields to go into schools to share their experience and inform children and young people of the supports that are available.

Source

Witness statement of Rūpene Amato (16 July 2021).

Footnotes

[1] The Inquiry notes Mr Amato cannot recall the identity of the priest who he says abused him. A subsequent investigation into the allegations by the Society of Mary has found that the priest is unlikely to be a Society of Mary priest.