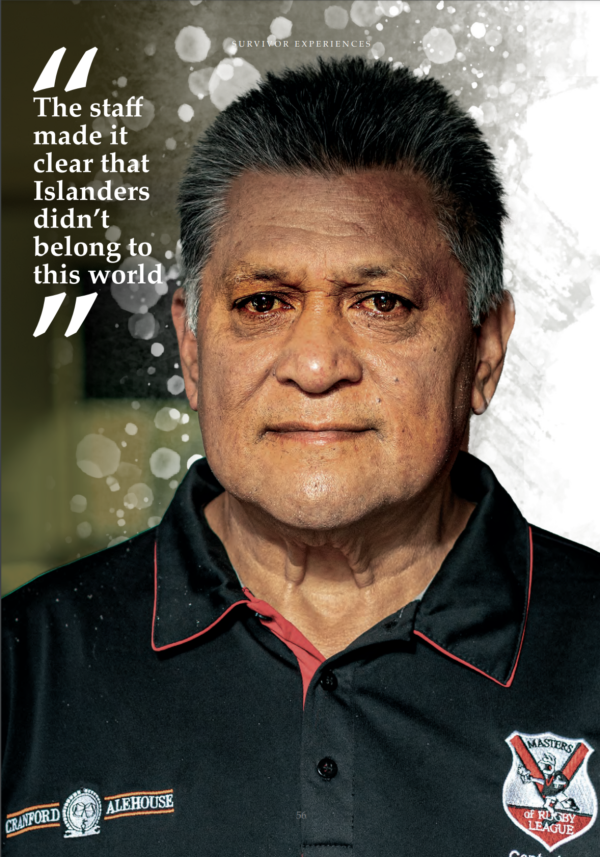

Survivor experience: David Williams (aka John Williams) Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Age when entered care: 9 years old

Year of birth: 1958

Hometown: Ōtautahi Christchurch

Time in care: 1969‒1974

Type of care facility: Boys’ homes – Ōwairaka Boys’ Home, Hokio Beach School, Kohitere Training Centre; borstals – Invercargill Borstal and Waipiata Borstal

Ethnicity: Samoan

Whānau background: David, two sisters and a brother grew up in Auckland with his grandparents, who became his guardians after his parents split up.

Currently: David has found sisters he never knew he had and is now part of a loving family. After many years, he finally has a sense of belonging.

I started running away from home when I was 9 or 10 years old. I just got sick of the bashings and sexual abuse.

When I was 11 or 12 years old, I was kidnapped. The kidnapper sexually abused me and threatened to kill my brothers and sisters. There was a nationwide search, with pictures of me on TV, and I was found when the neighbour saw me in the window and called the police. I brought shame to the family because of what happened to me.

The kidnapping was never noted in my Social Welfare file. After the kidnapping, I started running away from home. I got into trouble because of what I had to do to survive on the street. Nobody ever asked me why I was running away or why I was in trouble.

I was sent to Ōwairaka when I was about 13 years old. No one asked me what ethnicity I was but they knew who was Māori and who was a Pacific Islander. They never acknowledged our culture or ethnicity in a positive sense. You had the white boys who were treated not too bad. Then you had the Māori who were treated like shit. But then if you were an Islander you were dog shit. They would step all over you.

Staff used to tell me nobody wanted me and that I was useless and I should kill myself. At school in the classroom, they made the white boys sit at the front, the Māori boys in the middle and the Islanders at the back. School was a waste of time because you couldn’t hear anything from the back. If you asked the teacher to repeat anything he would come up to you and whack your knuckles with a ruler.

It was the sexual abuse that was the worst. I’ve shut it away for such a long time. A lot of things happened down in the secure unit but also outside of secure. I can still hear the screams and cries from other boys when they’d get taken into the shower block, where the abuse happened. I remember one time it was so painful because they thought it was funny to stick a bottle up my arse and watch me walk around.

My last time in secure at Ōwairaka, they kept me there for three weeks. I contracted a sexual disease but staff never got me to see the doctor because questions would have had to be asked about how it happened. I think that’s why I’ve never been able to father children.

I was transferred to Hokio. They came during the night and took me out of my room, and put me in secure but didn’t say why. In the morning, they put me in handcuffs and I was taken to Hokio.

There was a lot of abuse by the staff. Once when I was locked up in the cell, a staff member came in and sat on the mattress on the floor next to me. He talked to me as if he was my friend. It started by rubbing my leg and progressed from there. It wasn’t just me getting that treatment, you could hear the other boys screaming.

Going to school at Hokio was a privilege, which was ironic given it was called Hokio Beach School. If you misbehaved or ran away, you would have to mop, clean, vacuum and wash windows instead of school. A report in my files says that I was “probably the best in the class” at oral and written expression, and that I was “articulate and well conversant with language”. Another note said I had a good attitude to school work and that I had made “amazing progress” at school. But the abuse got to me and it became hard to focus on school. Later that year Hokio applied for a school exemption for me. I would have liked the opportunity to continue my schooling, but no one asked me.

At both Ōwairaka and Hokio they would drag you outside and give you cigarettes after abusing you. You had to smoke them as a reward, as if you agreed to the abuse and were being a good little boy. We were never smokers as kids, but if we didn’t smoke when we went in, we were big smokers when we went out.

Most of the boys at Hokio were Māori or Islanders. If you had brown skin, you were going to get abused. When I was being raped, both at Ōwairaka and Hokio, I was told “this is all you’re good for, you’re a coconut, you are the lowest of the low, you are just a piece of shit”. They’d refer to us as ‘coconut’ or ‘bunga’ or ‘fresh off the boat’.

When I was released from Hokio, I was told I wasn’t a ward of the State anymore. I was sent back to Auckland on a train, but my family didn’t want me back. I had nowhere to go, no money and I ended up living on streets. I slept in Myers Park and stole to survive for quite a while.

I didn’t feel like I could tell anyone about the abuse. You know what happens if you talk. Someone else in my family went through the same thing – we knew nobody would believe us. Social workers must have known about the abuse. When I wonder why they didn’t ask questions, I think it was because they already knew the answers.

What’s in my file is another form of abuse. Some of it is true, but not all of it. Reading that I was a bully, when it was the staff telling me to beat up other boys – I couldn’t believe it.

The things that happened, you can’t let go of it, it’s there for life. We wouldn’t be here if social workers had done their due diligence and did what they were meant to do. If I had been treated properly in care with no abuse, who knows what my life could be now.

I learned how to be a good criminal while I was in care. I have done three stints in prison. My last stint was in Dunedin Prison, 30 years ago. I woke up one morning and decided I’d had enough. When I got out, it was trial and error going straight, but a lot of the time I just stayed off the roads. I knew if the cops saw me they’d pull me over for something I hadn’t done.

Us survivors, we have no one to fall back onto. The only way we can get up is to do it ourselves. We can’t rely on anyone. That’s the way it’s been for a long time and why we feel the way we feel. I am a painter and I have also done a building course. I’m a health and safety officer. I am an MPI transfer facility officer. I’ve got my first aid and my forklift licence. Everything I have, I have worked for it off my own back. No one has given me money to help me.

I’ve had a good rugby league career and I’ve got good mates. People know me as a hard worker. I work 14 to 16-hour days. I’ve got a family who loves me and cares about me. But I’ve done that. No one has come and helped me.

I used to deny that I was an Islander because of what happened to me in the boys’ homes. I lost my identity because I thought nobody likes Islanders. Everyone thought I was a Māori, and that was alright. I had learned to keep my mouth shut. They pounded that into me, that we were no good, we were dog shit. You lose your identity. It’s not until the past four or five years I’ve started saying that I am a Pacific Islander.

I understood Samoan when I was younger. Now I only understand a little bit. In my social welfare file it says they had to carry on religion and culture, but they never made sure that happened. When you go into a home, you lose your culture and you lose your identity. You start to believe what they are saying about you. The staff made it clear that Islanders didn’t belong to this world. A lot of survivors turn to gangs, because gangs have treated them like family. They lost their history and mana and identity, just as I have.

They took a lot from my life and no one has ever given it back to me.

Source

Witness statement of David Williams (aka John Williams) (15 March 2021).