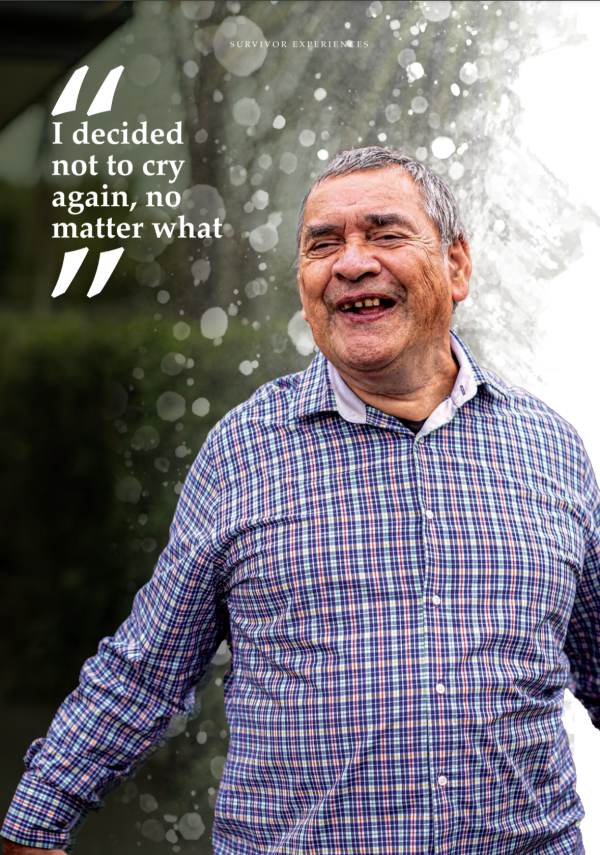

Survivor experience: Gary Williams Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Year of birth: 1960

Hometown: Tokomaru Bay

Type of care facility: Disability facility – Pukeora Hospital, Laura Fergusson Trust

Ethnicity: Māori (Ngāti Porou)

Whānau background: In Gary’s early years, he was very happy living with his whānau. He had five siblings. Te reo Māori was spoken in his community and they spent a lot of time at the local marae.

Currently: Gary is married and lives with his wife in Ōtautahi Christchurch. They both work for their own company.

I have cerebral palsy. This affects my muscles and my mobility. I am a part-time wheelchair user. I also have a speech impediment. When I was young, I wasn’t treated like I was disabled. I participated fully in whānau life on the marae and at school.

I started medical treatment when I was 2 or 3 years old, I went from Tokomaru Bay to Cook Hospital in Gisborne where I had physiotherapy. I also went to Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Rotorua. I was there for eight or nine weeks at a time. This happened for about five years, then I stayed home fulltime in my community.

I went to the local school Hatea-a-Rangi, which I enjoyed because I am an academic. When I was at Hatea-a-Rangi, I used to do my friends’ homework for them, and they’d reciprocate by helping whenever I needed. I was like the boss, I told them what to do and they did it. When I was in Form One, my family were planning to send me to the University of Waikato to study accounting. I would make a contribution to the community and to my iwi.

When I was ending my intermediate school years, I began planning my high school years. The nearest high school was in Tolaga Bay, which is forty kilometres from Tokomaru Bay. All my peers were going there. The Education Board decided that

that school would not be accessible for me, so I would need to be sent away to go to school. It was the 1970s and I believe the Education Board did not want to make school accessible for me because of the financial cost. This meant I would have to leave and go to school somewhere else.

I moved to Pukeora, Waipukurau, when I was 13 years old. Pukeora was a converted Tuberculosis sanatorium. It was a place that housed disabled people from all over New Zealand. There were about 80 people living there, and it was full most of the time.

It was a big change. I needed assistance to eat. The staff tried to make me wear a bib like everyone else who needed assistance to eat. I decided that if I had to choose between eating or wearing a bib, I’d stop eating. And I did. I stopped eating for a couple of days. I am so stubborn. The staff even called my mother to ask what they should do. Nowadays, I’d be labelled as having challenging behaviours. In the end, the staff gave in and I didn’t have to wear a bib. It was the first of many instances where I’d resist injustice and/or stupidity.

It was this physical isolation that enabled the abuse that occurred at Pukeora. Pukeora was in a little town where everybody knew everyone. Abuse happens when no one is watching.

I experienced cultural abuse and neglect at Pukeora. I am from Ngati Porou and the Māori staff that worked there were Ngati Kahungungu. No one spoke te reo Māori, not even the older Māori men residents. There was no Māori kai. I was very lucky that I had my experiences that I did when I was young at home.

At Waipukurau Hospital, there was Matron Pene who used to work at Te Puia Hospital and she knew my mother, so she knew me. Things were good while she was there. She retired after I had been at Pukeora for a year. Then things got hard. I was clever, I didn’t fit in the environment. I didn’t really have anyone I could trust and talk to about things. As there was no one I trusted, I kept things to myself. I was a loner, I learnt how to not get trapped by the predator types that lived and worked there. I think it was easy for people to take things too far.

A lot of the staff were untrained. The biggest employer in the central Hawke’s Bay at that time was the Peter Pan ice-cream factory. When the factory closed, the factory workers became workers at Pukeora. They didn’t know how to care for disabled people. A lot of the staff should not have worked at Pukeora but they couldn’t get anyone else to do the work. There was a staff hierarchy. I would try and avoid becoming over familiar with most of the staff because they worked together. So, there was not much point in complaining – nothing would get done. When the staff were unjust to me or anyone else, I stood up to it. I would say stuff like “I bet your mum would be embarrassed by you” or “real men don’t beat defenceless people”. Overall, though, no one bothered to complain as nothing would change.

I have excessive saliva and I dribble as a result. To fix this, they wanted to cut a gland through my ear to reduce or stop the saliva production. I went into Palmerston North Hospital on the 22 or 23 December 1975. This meant I couldn’t go home for Christmas. It was the first time I had been in a medical hospital. I had no idea what to expect. It was the first time I had surgery. It was horrible, my ear was full of blood. Saliva is natural and necessary for living. The operation didn’t work. I think that it was experimental surgery. I am not sure if my parents gave consent to the operation. Back then, doctors were treated like gods. It was unnecessary, and I was available for the experiment.

I was humiliated when I had to shower with others, I had no privacy. It was practical for staff to shower two or three of us at a time. Sometimes it was mixed genders. I hated it. I used to position myself so I couldn’t see the person behind me. The area was so small.

I am quite lippy, and I was willing to stand up to authority figures. I won’t back down. Staff tried to get retribution for my non-compliance. There were times when staff would put me on the toilet and leave me there. They knew I wouldn’t move in case I embarrassed myself. I couldn’t get their attention, the alarm cord that hangs from the celling was turned off. I would pull it, and no one would come. One time, they left me there for four hours. That kind of abuse didn’t leave physical marks.

I was 13 years old and I cried the first time I was punched. I’d never been hit before. It was a combination of shock, pain and humiliation. I decided not to cry again, no matter what.

I was innocent and naïve. I knew nothing about sexuality, it wasn’t in my consciousness. I was abused in the showers by a range of staff from older men to teenage girls. Pukeora was open slather for staff who sexually abused. Some of the staff

were quite open about the abuse, like it was a badge of honour.

I didn’t tell my parents about the abuse I was experiencing. I made the conscious decision to stay at Pukeora and not create turmoil in their lives. After all, they’d been promised I was only there until the end of my secondary education. Even now, after what I have experienced, I wont even tell my wife what I have been through.

When I left Pukeora, I moved to Laura Fergusson Trust which is in Naenae, Lower Hutt. I lived there for 17 years. I lived there with about 20 others, but I did not have anything in common with most of the others. The manager there employed her family to be staff. They weren’t trained.

After the 45 years I was in State care, I do not trust the system. The State has control and the power to make a difference. The State has powerful people making life and death decisions. Unfortunately, the people who make the most crucial decisions, politicians, are not subject-matter experts.

I don’t trust the system because it has let people down, I need to see change. We live in a sophisticated nation. In my view, schools that teach disabled people to fit the narrative of what a disabled person is – helpless, needy, dependent, vulnerable – are not helpful. Children need to be supported in their local communities and stay local.

It is a societal issue to find better ways to care and support people. The conversation that needs to happen is what will it take to support our people. In my view, I think that non-indigenous systems have not worked even for non-indigenous people. We all need to step back from the brink and figure out a move in a different way. I often think about pre-colonial times and ways of living and behaviour where Māori influence was the norm.

If things are done differently that way of life will surface again.

Source

Witness statement of Gary Williams (6 September 2022).