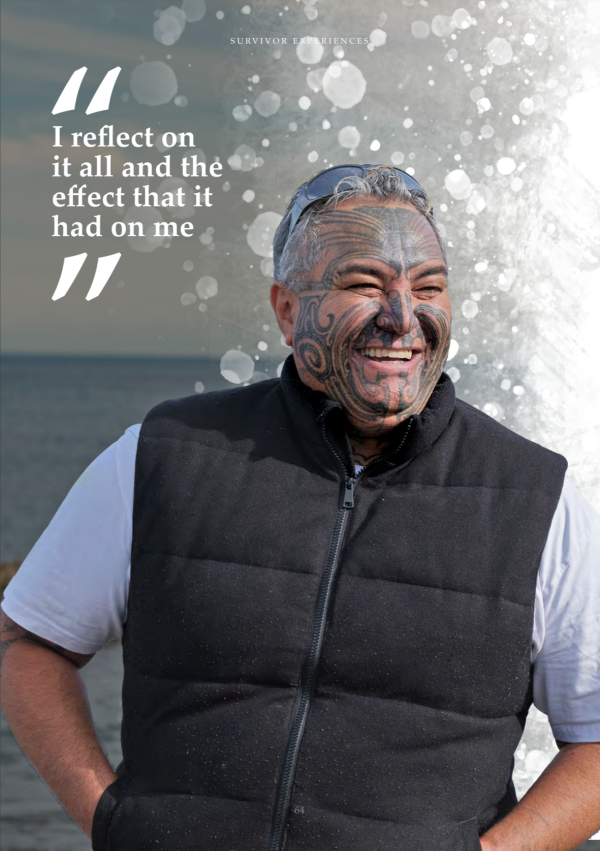

Survivor experience: Eugene Ryder Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Year born: 1971

Age when entered care: 11 years old

Hometown: Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

Time in care: Four years

Type of care facility: Boys’ Homes –Wesleydale Boys’ Home, Ōwairaka Boys’ Home, Kohitere Boys’ Home, Hamilton Boys’ Home; foster homes; faith-based care – Hodderville Boys’ Home (The Salvation Army).

Ethnicity: Māori (Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Kahu, Ngāti Kurī, Ngāti Tuwharetoa Ki Kawera, Te Roura and Mangukaha)

Whānau background: Eugene’s mum left when he was young. He and his siblings had a challenging childhood with their dad that affected his early feelings about being Māori.

Currently: Eugene is an E Tū Whānau-aligned social worker, legal student, kapa haka stalwart and dedicated husband and father.

I grew up in a home where abuse was normal. We didn’t think or see that as something out of the ordinary. Hidings were normal. I wanted to get away from that, so I started running away and living on the streets in Auckland. Because I was meant to be at school I often came to the attention of police. They would threaten to take me to Wesleydale Boys’ Home or back home. I told them I wanted to go to Wesleydale.

One of the staff at Wesleydale used to encourage us to run away. He said we could stay at his house. When we were there, he would rape us. It was the first time I was sexually abused. There was this other Samoan staff member, he was fucking evil. He liked disciplining people.

One day I was mowing the lawns, I don’t know exactly what I did but he picked up a rake and broke it on my back. I tried to run to the nurse, but he stopped me. That rake became a symbol because he kept the end of it. When he was on shift, he would drag me into the showers and ram the handle of the rake up my arse. I ran away that morning, but the police caught within hours. When I got back, he was still there, even though his shift had finished. He was waiting for me.

I was telling the police officers not to let him near me, and I started attacking them with the hope they’d drag me away, but they didn’t. They let him grab me by the hair and drag me back into the showers. I was screaming like fuck. I assume the other staff knew what he was doing because they would all disappear when it happened.

I remember going to the doctor after I got the rake shoved into me and he didn’t care. He fondled me pretending he was looking for damage and he was playing with my balls. We knew not to go to the doctor because he was a threat. So, even if we were hurt, we wouldn’t go to him. Every new boy had to go and see the doctor. He would grab our balls and say, “cough” and he’d keep saying, “cough”. We’d be in there with him for ages.

Because of the abuse I was becoming more and more rebellious. When I was 12 years old, they sent me to Ōwairaka because they had a secure unit there. You had to be 13 years old to be at Ōwaiaraka. Because I was only 12, they kept me locked up in secure all the time and I could only come out for meals.

Ōwairaka became a goal because that’s where the big boys were and they got issued a cigarette at every meal, whether you smoked or not. When shit happened in Ōwairaka I expected and got a hiding every time, even if I had been locked up at that time. Like a man hitting a man, not a child. It was punches and kicks. We weren’t allowed to see anyone from the outside until we were healed. My old man used to try and visit but he was always told that I had been playing up so wasn’t allowed visits.

I was sent to a few foster homes too. They weren’t any better. The dads were beating their kids and raping their daughters. At one home, one night I heard him raping his daughter and so I ran away to see if I could make it to this huge riot that I knew was happening in Auckland. Because of that I got shipped to Kohitere in Levin.

At Kohitere there were ‘social workers’, they called themselves, that were evil. This one guy who was at the ‘pound’, would beat the shit out of us if we looked at him wrong or did something wrong. He was either in the Vietnam or Korean War and he showed us photos of the Viet Cong where they had chopped the Viet Cong’s dick off and stuffed it into his mouth. He said that’s what he’d do to us. So, every time he said something we’d jump, it didn’t matter.

That pound was terrible. I remember one time he broke both arms of this fella during a beating. They told authorities that he broke his own arms to get out of doing forestry work.

There was another guy who was running the forestry workers at Kohitere. He would make us eat shit if we wanted a cigarette, like literally eat shit. Whoever had done a shit – that’s what we had to eat. He’d crack up about it. Those of us that didn’t eat it would get sent to the pound. The pound was where the other guy was so, it was eat shit or get the bash. Because I was used to getting the bash, I’d just go there and get it.

Kohitere wasn’t all bad. They saw me as a bright spark and so I was the first one there to go to Waiopehu College, but the college wouldn’t let me go there with the rest of the kids, so they had a special class for me at night, and I’d go to school at night.

Somewhere in that mix I went to The Salvation Army’s Hodderville Boys’ Home. I must have been 13 or 14 years old by then. That place was the worst. When I first got there, I was so scared, I pissed the bed. Someone noticed, they all started making fun of me. One of the captains dragged me out because I was screaming because I was getting a hiding.

At first, I thought he was there to help me, and I was thanking him. Then he told me that I caused it, and then I knew he was going to give me a hiding. He stripped me off and I had to bend over a table, naked. He’d take a run up behind me and whack my arse so hard my head would hit the table.

Kohitere was the last place I was in. I think I was 15 years old by then. I didn’t want to leave because leaving meant going home and I didn’t want to go home. You were only meant to be there for three months, but I pleaded for them to let me stay so they let me stay another three months, just to not go home.

I discovered gangs in Kohitere. I had uncles that were Stormtroopers and cousins that were Mob, but they weren’t an influence on us. But, in Kohitere, you had to pick a gang. At first I was a Stormtrooper and when the numbers were unbalanced we became Mongrel Mob. The day I left we were Black Power.

Years later, I ended up coming across that social worker from the pound at a tangi. When we were going around for a hongi, I was so scared I was sweating. I was thinking to myself how badly I wanted to punch him. When I got to him, I said, “remember me?” He said, “yeah, yeah, yeah, I seen you on TV.” I said, “No, in Kohitere.”

He went white. When I saw that I said, “Oh, no, I forgive you, bro” and just hongi him and carried on. I don’t think I did forgive him, but I saw him as someone’s koro and I don’t want to be responsible of putting someone’s koro in prison.

I try and think about the fun times, because I had a bit of fun in there. But that fun wasn’t what society thought was fun. I reflect on it all and the effect that it had on me. When my daughter was born, I didn’t want to be alone with her. I didn’t want to change her nappies or bathe her because I was scared to become an abuser.

One day, when my daughter was 3 or 4 months old, my wife went to the shop and was away for a couple of hours. When my wife got back, she was angry with me because I hadn’t changed my daughter’s dirty nappy. That’s the day she found out what happened to me. I told my wife I didn’t want to be seen or thought of as an abuser. Because I thought sexual abuse was normal, it wasn’t until I talked to my wife that she told me it wasn’t.

That was the first time I had had a kōrero with anyone about it. I felt released. Then I became the only one that bathed my daughter.

Source

Private session transcript of Eugene Ryder (17 December 2022).