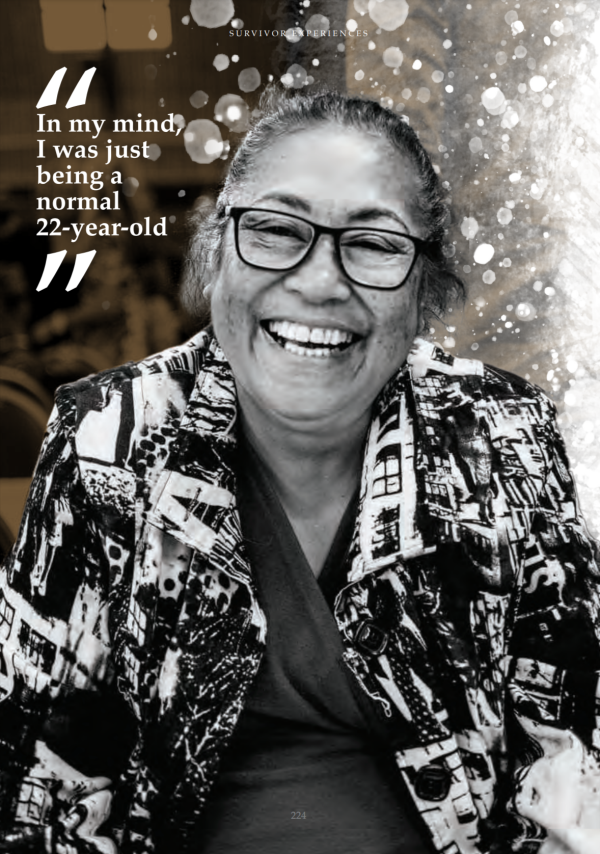

Survivor experience: Rachael Umaga Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Age when entered care: 28 years old

Year of birth: 1964

Time in care: 1992–2013

Type of care facility: Psychiatric care – Ward 5 Hutt Hospital in Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai Lower Hutt, Te Whare Ahuru Acute Inpatient Care Unit in Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai Lower Hutt.

Ethnicity: Samoan

Whānau background: Rachael is Mum to Soraya, Grace, Thomas and Peter; and Grandma to Jensen, Fox, Maleki, Elliot and Kylo.

Currently: Rachael passed away on 13 February 2024.

My first experience with the mental health services was in 1986 when I was 22 years old. My parents thought that my behaviour was concerning and that I was mentally unwell. I had dyed my hair bright orange and was partying a lot. I was flatting with my friends at the time and believed I was just enjoying life. They thought this was behaviour that was not befitting of a young Samoan girl at the time.

My mum worked as a nurse in the Hutt and Porirua and I thought she was well versed in picking up ‘behavioural issues’ from her nursing experience. My dad was primarily concerned about what the church people thought. He was stern but was also looking for answers about why I was behaving the way I did. In my mind, I was just being a normal 22-year-old.

My dad took me to see two mental health professionals at Ward 27 in Wellington Hospital for the ‘behavioural issues’. The professionals concluded that I did not have a mental health issue. I was not put on any medication nor was I admitted to a psychiatric unit on this occasion.

I continued to work in Wellington and then moved to Hamilton. My partner at the time was abusive and I was physically and emotionally abused during that relationship.

In 1992, I left a violent relationship and sought a protection order against him. I moved in with my friend and my ex-partner kept trying to visit me at her house. I remember I wasn’t able to sleep. I had to take time off work because I couldn’t cope anymore. That is when the ‘mania’ started.

My family and friend decided to take me to Ward 5 at Hutt Hospital. This was a traumatic experience for me. They literally picked me up and threw me into the back of the car. My friend’s husband was seated at my head, my brother was holding me at my feet and one of them was sitting on me until we got to the hospital.

I remember the psychiatric registrar asking me, “Why do you think you’re here?”. I said, “Because you guys don’t see the real problem.” I was referring to the fact that I was a victim of abuse, I needed help, but I was the one being admitted to the ward instead of my abusive ex-partner, who remained in the community.

Medical professionals described my behaviour as “hypo-mania” but for me, my behaviour was a culmination of the physical, mental and emotional abuse I received, and a lack of sleep. This admission was done informally. I discharged myself from the ward 15 days later but was then re-admitted three days after that on a formal basis.

I was put in a room with five other unwell women. There were no curtains to give us privacy. I was given a lot of medication and I was never told exactly what the medication was.

When I decided to leave, the psychiatric registrar threatened, “If you leave, I’d make sure you never leave again if you came back”. I also remember one of the psychiatrists on the ward telling me that he could guarantee I would be back at the unit in a few days. A few days after I discharged myself, I was re-admitted to Ward 5 following an incident where my legs gave way and I couldn’t walk. On admission, I was made to sign a contract. This meant that I was sectioned under the Mental Health Act and was only permitted to go on escorted leave with a family member or a nurse.

I was put into a seclusion room. I remember the nurses sedating me to bring my energy levels down and them having to restrain me to the bed. The seclusion rooms were like a cell, there was no water given and no toilet.

I stayed at the unit for a couple of months until I was discharged on 19 November 1992. During this time, I was in seclusion for a long period of time.

Over the years I was admitted into care 11 times.

Te Whare Ahuru was meant to be a place of calm. This to me was anything but calm.

I had to take so many pills, possibly as many as 13 pills at a time. As a result, my kidneys started to fail. Prior to my admission into psychiatric ward, I was not on any medication at all. I didn’t even like to take Panadol. In 2009, I had to undergo dialysis treatment. My renal function continued to deteriorate and in 2011 I had a kidney transplant.

I felt like I was placed in seclusion for long periods of time. I just want to be clear that I don’t ever want anyone in the future to experience seclusion. It is lonely and boring and makes you feel like you’re an animal in a cage. We have no freedom. The staff just leave you in there, and there is nothing for you to do.

A lot of the time, I did not feel safe at Te Whare Ahuru and did not feel staff listened to my concerns. There was negativity from medical professionals and other patients. Staff were falling asleep on night shifts. Patients were also intrusive and abusive. I had limited contact with my whānau. It was not a healthy environment for me.

Throughout my admissions I was diagnosed with various conditions. However, the diagnosis did not make sense to me. During my first admission I was diagnosed with post-natal depression. This did not make sense to me because my daughter was 2 ½ years old. Then I was diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Later, I was diagnosed with epilepsy, which tests confirmed was wrong. To me, I felt like I was ‘labelled’ with a particular medical condition that gave medical professionals a licence to pump me with more drugs. I believe they were just experimenting with their drugs on me.

When I was reviewing my medical file, I noticed other labels being used by staff throughout my admissions. These ‘labels’ included mania, hypomania, psychosis, bipolar disease, depressive phase of my illness, suicidal ideation, schizo-affective

disorder, elevated mood, depression and sedated.

These labels were hurtful and degrading, and I could not help but wonder why they did not inform me about what they were writing at the time of writing. I was never told of these conditions and neither were they explained to me.

Medical staff often got my ethnicity wrong despite me telling them constantly that I am Samoan. To me, this showed that they were ignorant and careless, and it did not help the situation if they were not getting the basic things accurate. The staff assumed what ethnicity I belonged to and that did not sit well with me. It caused an unfavourable reaction from me because they often did not get the simple stuff right.

There was no creative outlet, just some walks around the hospital grounds. I believe that options such as Samoan fofo or Māori massages should be readily available because they worked well for me.

My time in psychiatric care has also impacted my lifestyle. I went from being a very active mum to be an isolated, shy and quite introverted person, fearful of being in social settings. Even doing the shopping became a problem for me. I had this fear that everyone knew I was on a psychiatric ward, so they judged me or labelled me before they got to know me.

The feeling of shame is very real. For people that have been in these units, they carry the stigma of shame. We feel shame. Shame stops us from making friends. The stigma makes us untrustworthy of people, always insecure and cautious of people all the time. I am often questioning people whether what they are proposing is in my best interests because of my experience. I used to be outgoing and an extrovert. I have been forced by the shame to behave differently and to be more introverted.

In the 1990s, a staff member asked me, if I was in charge of Ward 5, what would I change. I told them that I would not have it attached to a hospital. I told her it would be like a retreat. It would have a sea view or be in the country, where it would be therapeutic and where you could walk in nature (really walk in nature as opposed to fake grass). You would have massage therapists, you would have art, and you would have music. You would have all the things that people could be passionate about to help them become well. It would all be about wellbeing.

I guess the question for me is, who are going to be the reformers and who is going to make sure that there are big changes for the future of care? I believe that survivors are a good start to consult with.

Source

Witness statement of Rachael Umaga (18 May 2021).