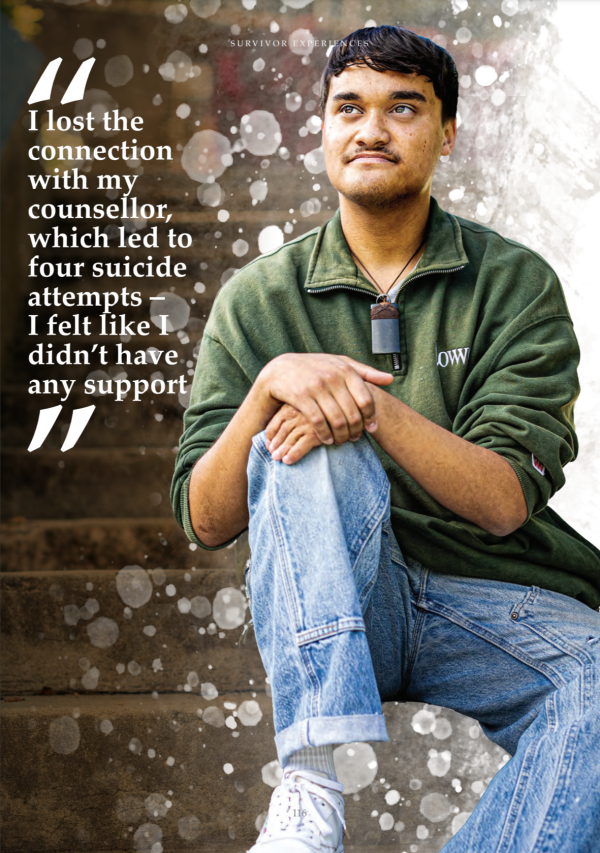

Survivor experience: Ihorangi Reweti-Peters Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Year of birth: 2005

Year of birth: 2005

Hometown: Ōtautahi Christchurch

Time in care: Foster homes; family homes; residential school – Halswell Residential College; transition home; psychiatric hospital – Princess Margaret Hospital Inpatient Services.

Ethnicity: Māori (Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Tahu-Ngāti Whaoa, Ngāti Kahungunu)

Whānau background: Ihorangi’s father is Māori and his mother is Pākehā. He has two brothers and one sister – he is the youngest. His parents separated when he was 7 months old.

Currently: Ihorangi lives with his grandfather. Ihorangi is committed to his advocacy work for rangatahi and tamariki in care. He is on the Christchurch Youth Council and also won the 2021 Prime Minister’s Oranga Tamariki Award for Te Iho Pūmanawa – Whakamana Tangata and the 2021 Young Change Maker Award at the Waitaha – Canterbury Youth Awards.

I was uplifted by Oranga Tamariki when I was 7 months old. My parents had separated, and there was violence and drinking and drugs at home.

My sister and I went to live with my grandparents. My older brothers stayed there too for a while. My grandparents were awesome and provided me with a loving and nourishing home. But due to my parents’ addictions, and not receiving the best start in life, I was left with disabilities and behavioural and mental health issues.

At 10 years old, I started to feel angry and would sometimes become violent towards my grandparents. I was removed from their care and sent to live with another family member. My social worker told me my grandparents didn’t love me and didn’t want me back.

I’d never met or even heard of this person before then and my social worker didn’t tell me anything. I cried all the way there because I was scared. They lived by themself on a rural property. I was with them for about 12 days before I ran away because they hit me. The first time, they were using PVC pipes to round up sheep. I left a gate open and they threw a pipe at me. A few days later, they smacked me around the side of my face. I decided to run away, and they threw one of the pipes at me again. I walked for 90 minutes to the police station and complained. The next day my social worker flew me back to Christchurch.

No one asked me where I wanted to go. I was just told I was going to be placed in a family home – they said just for one day but I was there for five months initially and went back several times over the next few years. Heaps of different boys came through. I shared a room with one boy who got undressed, rubbed his hand on his bum and wiped poo on my bed. He was bigger than me. He was taken away but returned a week later – it felt rough to see him again.

My grandparents visited and advocated for me, including around my mental health. But the caregivers said they treated me like a baby and banned them and other parents from entering the house. After this, I noticed their behaviour towards me changed and I was treated differently to the other boys. They had their favourites – at Christmas, the Pākehā boys got PlayStations and Xboxes but I got a couple of T-shirts. I didn’t get the same amount of pocket money, either. The caregivers also refused to help me with my homework – they claimed the other boys didn’t have any homework so I was just seeking attention. When I reached out for help with my mental health, they claimed it was “just bullshit” and that Oranga Tamariki wouldn’t supply the correct support.

When I was 11 years old, I went to live at Halswell Residential College for about 18 months – I also went to school there. On weekends, I stayed with my grandparents and during the week I lived in the Māori Villa with five other boys. I loved it there because I got help with different problems like my anger. It was supportive and calm and there was no abuse. A Māori tutor taught me about my heritage – where I was from and about my iwi in Taupō, Ngāti Tūwharetoa. I also spent Friday afternoons horse riding at the Disabled School for Riding. I really enjoy riding horses, and the teacher thought I was good at it.

I had to leave Halswell because the funding ran out. I didn’t want to leave, but you can’t stay there for more than two years anyway. I went to stay with my grandparents for two weeks and then I was placed with two caregivers. They were Pākehā with no other children in their care. For the first few months, it was fine but they were heavy drinkers and they’d get angry when drunk. I was physically abused, punched and kicked. I had never been hit like that before. The man hit me more than the woman did – he’d get aggressive, telling me to “fuck off” and “get out of my house”. He was controlling. I talked to them about them hitting me and they said they didn’t know what else to do with me. I also told my teacher. I didn’t want to stay there after the abuse. They asked a social worker to take me away.

I was then placed in a transition home for a few months. The man who ran would smoke weed in the garage, and in front of the other kids in the house. This didn’t sit right with me but I didn’t tell anyone because I thought I might get into trouble.

In 2020, during lockdown, I stayed with my grandparents. After lockdown, I lost the connection with my counsellor, which led to four suicide attempts – I felt like I didn’t have any support. After the fourth attempt, I was placed under the Mental Health Act and taken to Inpatient Services at Princess Margaret Hospital.

VOYCE Whakarongo Mai is an independent advocacy service for children in care. They advocated with Oranga Tamariki for me to get a new social worker because of my then social worker’s behaviour towards me. By the time I went to hospital, I had a new social worker but my previous one turned up while I was there, stood over me and yelled at me. He dismissed my mental health and said I was “attention seeking” and “just trying to get what I want”. It was so loud and abusive that a charge nurse came in and told him to leave and not return.

I was in hospital for a week and a half and then I was moved to another family home. It was hard there because Youth Justice kids were mixed up with care and protection kids and the Youth Justice kids beat the other kids up. I felt anxious and weird while I was there. On my first day, I went over my crisis action plan with the caregivers, but they were dismissive and said I didn’t need it.

I made more suicide attempts while I was there. After my fourth attempt, they said, “We need to talk to you. Your suicide attempts are fucking bullshit.” They asked me if I was doing it to get attention and said my anxiety was fake, there was nothing wrong with me and accused me of crying wolf. After this I ran away and refused to go back. But the police found me, placed me in a temporary family home for the weekend and then I was sent back to the earlier family home for two months, until I was placed with a foster family.

Since I was 10 years old, I’ve been in seven placements. This has meant my connection with my own family has weakened. I don’t talk to my brothers anymore – like my parents, both have been imprisoned. I know my feelings of anger, suicide and stress come from being abused while in State care. Through it all, I have learnt to deal with these feelings with the support of my grandparents and VOYCE Whakarongo Mai, whom I now work with.

In May 2021, I spoke at the Child Poverty Action Group Post-Budget Breakfast and made two calls of action. I asked the Government not to remove the Royal Commission’s requirement to look at modern day care policy settings. That call to

action by me, and others, was answered.

I also asked for improved access for mental health and counselling and wellbeing support for rangatahi and tamariki. I am aware that 2,700 young people in care are described as having a mental illness and 80 percent of young people in State care have had at least one suicidal thought in their lifetime. I believe if Oranga Tamariki took this issue seriously then those figures wouldn’t be so high.

My speech meant I was invited to meet the Oranga Tamariki chief executive to discuss how mental health and wellbeing needs to be taken more seriously at all levels in that agency. My own experience shows that staff there do not take mental health seriously.

I have received support from local members of parliament to draft a Bill that makes properly resourced mental health and counselling support a statutory entitlement for every young person in care under the Oranga Tamariki Act. Part of my mahi at VOYCE Whakarongo Mai is to facilitate some group discussions and gather young people’s voices to add weight to the Bill.

I have many goals. I don’t want other rangatahi and tamariki to endure the abuse I did while under the care and protection of the State. I want parents of children in care to have access to free counselling and drug rehabilitation services so there is hope the family unit can become one again.

I believe Oranga Tamariki has a responsibility to help tamariki and rangatahi Māori visit their marae. This should be a priority.

I am trying to build my knowledge of my whakapapa (genealogy), but it’s challenging as Oranga Tamariki don’t want to give it to me because they say it is confidential.

I would like an apology from Oranga Tamariki and the minister responsible for that agency.

Source

Witness statement, Ihorangi Reweti Peters (18 January 2022).