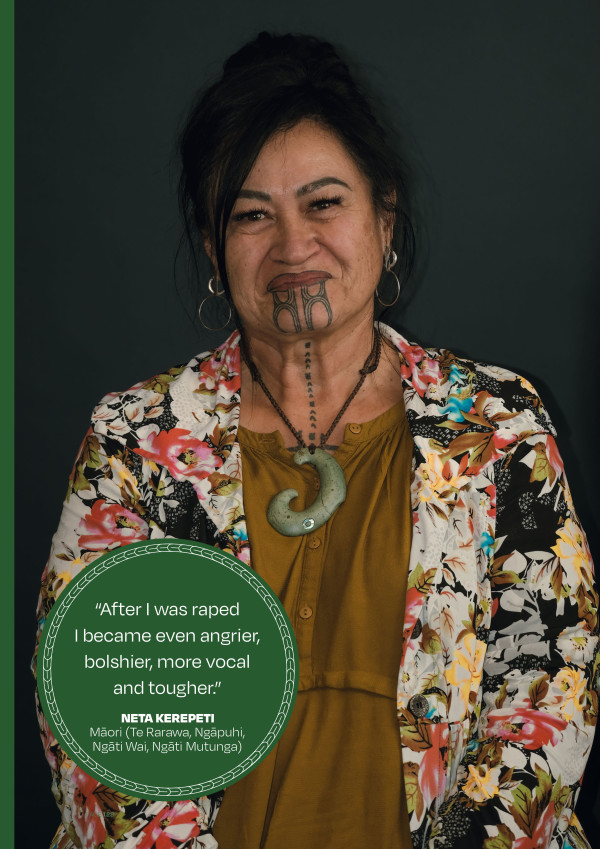

Survivor experience: Neta Kerepeti Ngā wheako o te purapura ora

Name Neta Kerepeti

Hometown Whangārei

Age when entered care 12 years old

Year of birth 1961

Time in care 1974‒1978

Type of care facility Foster care; girls’ home – Bollard Girls’ Home in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

Ethnicity Māori (Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Wai, Ngāti Mutunga)

Whānau background Neta is the youngest of 10 children, her mother died when she was 6 years old. She was cared for by father between the age of 8 and 11, and again between the ages of 15 and 16 years old.

Currently Neta is married with a family – she is the proud nan of 16 mokopuna and nine mokopuna tuarua, all of whom are flourishing.

When I was 12 years old I was removed from my home for truancy, then placed into care with evil people and within institutions where I was abused.

My mother died when I was 6, and it all started to go wrong from there.

I grew up in Ngunguru, a small settlement on the north-eastern coast from Whangārei. There was a real sense of community there, with all my whānau living in the area. Te ao Māori and te reo were a big part of my upbringing. It was the language the old people would speak to us in. It was all around us.

I was the youngest of 10. My mother was from Panguru in the Hokianga, and of Te Waiariki, Ngāti Manawa, Ngāti Korokoro, Ngāi Tūpoto whakapapa, and connections to other tribal groups. She was known as a tohunga rongoā, and a hunter gatherer; a resourceful, kindly, and well-loved woman.

My father connects me to the hapū of Te Waiariki, Ngāti Kororā and Ngāti Takapari, in the Horahora and Ngunguru rohe. My father was many great things, but he was also an alcoholic and an abuser. My earliest childhood memory of being abused was at his hands, between the ages of 8 and 11 years old. Despite that, I continued to love him, and I’ve since been able to forgive him.

I started to realise the abuse I was suffering wasn’t right and it was affecting me in different ways. By intermediate school I was acting out and truancy became one of the reasons I came to the attention of the authorities. My records from Whangārei Intermediate School in November 1974 say I was “increasingly aggressive, belligerent, obstructive, defiant...”.

I was once picked up by a policeman in downtown Whangārei. Instead of taking me home, he took me to Tikipunga Falls where he parked up and attempted to rape me. He said no one would believe me if I talked about it because I was a naughty child and had a reputation for being wayward. I was only 12.

The day I became a ward of the State I was taken out of the Whangārei Court and placed into a room by myself. I had no idea what was going on. No one told me why I was being taken away from my whānau.

That day my father had been summoned to appear in court because of my truancy from school and for not having proper care and control over my behaviour. That seemed to be enough for the Court to make me a ward of the State. Both my father and I should have had an advocate at the Court to begin with. My father wouldn’t have known what was going on and what the impact would be on his child and whānau.

I was placed into the hands of the Department of Social Welfare. From the start of the Court process, the police were there to deliver me, pick me up and take me away. The social worker was there to tick boxes and it was all process driven but there was no one there to explain to me what was going to happen.

First, I was placed into a family home in Whangārei with a Pākehā couple with about six or seven other kids, who were wards of the state also. The mother would treat some of us differently because we were Māori. The father was an abuser and so was their oldest son. I remember thinking ‘why was I removed from my home for truancy and then placed into care with evil people who were abusive?’

I hated it so much at the family home that I ran away. I was eventually found at the Whangārei port. I was taken back to the foster home, but I continued to run away as I couldn’t stand it there.

I spent some time in another family home run by a lovely couple in Onerahi, as well as with private foster families. They were good people, but culturally we were miles apart. It wasn’t an option for me to go where I wanted or to live with whānau.

As a 13 year old under the guardianship of the Director-General, Department of Social Welfare, I was incarcerated at Bollard Avenue Girls' Home in Avondale; apparently for increasingly uncontrollable behaviour, truancy and running away from school.

It was all new for me. There was no one there to support me or tell me what was going on.

Most of the girls there were Māori, at least three quarters. There was no acknowledgement of Māori culture there.

On entry to Bollard I had to be seen by a doctor who examined me to see if I had a venereal disease. There was no nurse, only a male doctor. He made me lay naked on the bed with my legs apart and feet in stirrups. I was never told why he was doing this; it just happened to me.

I also learned very quickly at Bollard, that if you behaved yourself, you got certain privileges, including the privilege of cleaning a staff member’s house. One day I was chosen, and he raped me at his home.

Sometime after I remember waking up one morning with bad stomach cramps. The sheets of my bed were covered in blood. I was miscarrying. I went to the office to speak to the house mother. I was told to run a bath and wait for a doctor.

It was about four or five days later before the doctor saw me. By then the bleeding had ended.

I later spoke to a staff member and told her I thought I had just had a miscarriage. She didn’t believe me, she said I was just having a heavy period. Following this experience, I was seen by a doctor, different to the one who examined me to see if I had a venereal disease.

Through the Commission’s inquiry process, it has been revealed from notes on my State file penned by the doctor who saw me after the miscarriage, that it is highly likely I did indeed suffer a miscarriage, given at the time, the symptoms I described to the doctor.

Bollard became too much for me. I had not seen my whānau, and after I was raped by the principal I became even angrier, bolshier, more vocal and tougher. I tried to run away – about four of us ran away and two managed to evade the police but eventually we were caught and returned to Bollard.

When I was 14 I ran away again, and this time I stayed away. I went down to Auckland, hitch-hiked to Wellington. I lived on the run for about two years; living on the streets, under bridges, in the bush, just living rough generally and surviving any way that I could.

At 16 I was wandering around Whangārei and decided not to hide anymore. I ended up going down to the wharves and on the ships. I made some friends there. I got involved with substance abuse, then I got pregnant. I had my first child when I was 16, in March 1978.

I was discharged from the care of Social Welfare later that year.

I had trust issues with people because of the abuse I suffered. One of the things I learned from sexual abuse ... was the art of manipulation, and that if I gave something, I'd get something in return. Abuse, sexual abuse, taught me how to manipulate people, and that sex could be used to get what I want.

After studying social work at Victoria University, I worked for CYFS for many years. I now work as a general manager for my hapū, managing our ahu whenua trust located in Te Tai Tokerau.

I journeyed a pathway through counselling, taking advantage of that counselling and as many sessions as I could get.

During these phases I met and became incredibly close to a wonderful Māori woman, who my whānau fondly refer to as Auntie Miriama ‒ her name was Miriama Kahu. She was born and bred in Kaikōura. She passed away several years ago but she was the dearest of friends. I attribute much of my healing to her. She took me to places I really didn't want to go to confront the doubt and damage resulting from my childhood sexual abuse. It doesn't matter how many times anybody said, and might still say … "It wasn't your fault, it wasn't your fault", there is this little seed of doubt.

I don’t want the State to intervene in my family’s life. It’s incumbent on me and other family members to ensure that we step up to the plate. To ensure that the safety of the child remains paramount, and yes, we may need some help to be the best family/whānau caregivers that we can be. I struggle to see how it can be fair that we/Māori, should not receive access to resources to meet those familial obligations and responsibilities, especially when we know because evidence exists confirming that complete strangers, mostly non-Māori, would have ready access to such resources as the ‘chosen ones’ to look after our Māori children.

I think if we want a system that is not racist and if we want a system that acknowledges tāngata whenua and all citizens, then we want a system that not only talks about the Treaty in principle but applies the principles of that Treaty. It's going to require a major shift in the system and an attitudinal and behavioural change in the people who are part of that system.

Any change needs to involve the entire system ‒ the Courts, Corrections, the police and social workers, education providers, as well as all other institutions that have contracts, obligations or responsibilities to ensure the safety of tamariki and mokopuna. And change can’t be made in isolation from the people whose lives will be either improved or impacted by such change.[423]

“I remember thinking ‘why was I removed from my home for truancy and then placed into care with evil people who were abusive?’”

Footnotes

[423] Witness statement of Neta Kerepeti, (22 April 2021).